How do you stay decent when blind hate-driven violence is rampant all around? In the hour of the trial, Albert Battel, a Wehrmacht lieutenant, did so. To save the Jews crammed into the Przemyśl ghetto, he was not afraid to oppose the SS, which attracted the attention of Heinrich Himmler himself.

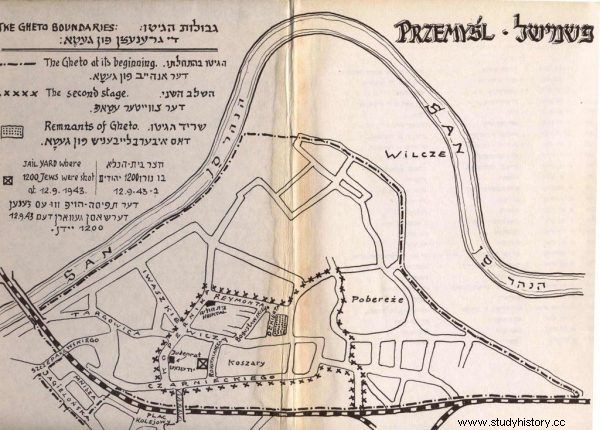

The morning of July 26, 1942 in Przemyśl was strange. For three weeks, a Jewish district operated in the right-bank part of the city, in which the Germans gathered about 22,000 Jews from the entire poviat. At that time, a certain rhythm of life had established itself. Every day sanitary transports arrived by rail, bringing wounded soldiers from the Eastern Front . From among all prisoners, the Wehrmacht selected men aged 16-35 for its needs. They were referred to as the Jewish auxiliary forces, Betrifft Judeneinsatz. Initially, there were several hundred of them, but this group was quickly expanded to four thousand people. Their task was to ease the German war machine by working in tailor's, tinsmith's, shoemaker's workshops, etc. Working under the auspices of the army, they felt chosen. The military provided protection for them. Major Max Liedtke was the commander of the city on behalf of the Reich army. His adjutant was Lieutenant Dr. Albert Battel.

The ghetto in Przemyśl

Decent Lieutenant

Albert Battel was born on January 21, 1891 in the village of Klein-Pramsen (today it is the Polish village of Prężynka, located less than ten kilometers from Prudnik). He was a soldier in the Prussian army during World War I. When he changed his uniform to civilian clothes, he started studying economics at the University of Munich, and then law studies in Wrocław. In 1933 he became a member of the NSDAP.

Five o'clock in the morning. The brigadier of the Jewish workers' column, Samuel Igiel, rushes to Conrad von Hotzendorfstrasse (now Wybrzeże Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego Street) to the Ortskommandantura No. 573 of the Wermacht. The previous evening, the ghetto was cordoned off from the rest of the city by cordons of Sipo and Polnische Polizei im Generalgouvernement. A rumor of displacement began circulating among the Jews. Only prisoners who could identify themselves with a special Gestapo stamp were to be excluded.

After the war, Igiel testified before the Military Jewish Historical Commission:

[...] out of our group of 4,500 employees, only 150 people can receive stamps. This meant that the overwhelming majority, 4,350 people, were sentenced to displacement. There was no time to waste.

He understood that resettlement was essentially death. To figure it out, he did not need to know about the details of the arrival of SS-Hauptsturmführer Martin Fellenz to Przemyśl, a man who brought with him instructions for the extermination of Jews from the General Government and the Białystok region. The action agreed six months earlier, during a conference organized by SS-Obergruppenführer Heydrich, in a villa on Lake Wannsee, which was named Einsatz Reinhardt in his honor. Liedtke and Battel were not admitted to this knowledge either.

Przemyśl - the burning synagogue

The latter had already attracted the attention of the SS. Despite being a member of the Nazi party, his attitude towards Jews was reprehensible in the eyes of his party colleagues. Even before all hell broke out in World War II, he had to stand before a party tribunal for granting a loan to a Jewish friend. Later, in Przemyśl, he was reprimanded for shaking hands with the chairman of the local Judenrat, Dr. Ignacy Duldig. When, on that July morning, Samuel Igiel managed to inform him about the encirclement of the ghetto, he immediately contacted Major Liedtke. Both tried to intervene with the head of Sipo and SD in Przemyśl, SS-Untersturmführer Benthin. They argued that depriving the Wehrmacht of manpower was unacceptable. They didn't do anything. The expulsions were ordered "by a special secret order" . After consulting with other officers of the Ortskommandantura, Battel made a bold decision to block the bridge over the San, the only way to the ghetto. His supervisor accepted the idea:

Gentlemen, I know the risk is high as this plan goes against Himmler's explicit order, but for us it is more important to provide manpower for the Wehrmacht.

Insubordination

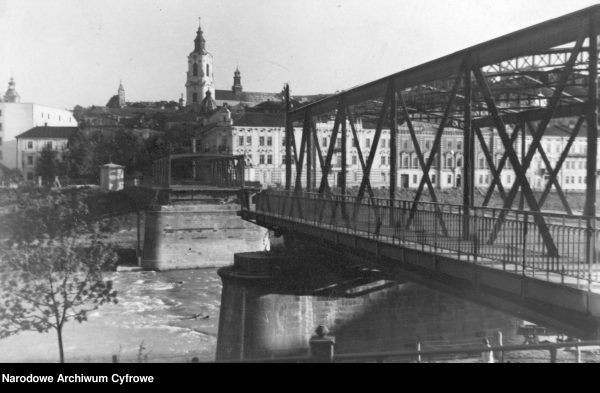

This sight of outsiders must have stunned and caused quite a consternation. On one side of the bridge, the Waffen-SS troops, on the other, a machine gun aimed at them. Stanisław Dąbrowa-Kostka, a Home Army soldier, saw this situation closely:

The machine gunner - gunner and ammunition - was in a combat position. An off-road police car came from the side of Krasińskiego Street. The officer stopped the vehicle with a movement of his hand and shouted:Halt! Uniformed Sipowcy got out and tried to approach, but he would not let them, and those at the railroad slammed the locks menacingly. There was a loud gibberish. The fight lasted at least a dozen or so minutes. In the end, the enraged Sipowcy drove away to ul. Krasiński (...). We quickly received information that the parties to the conflict were after the Jews.

There were feverish conversations behind the scenes of the bridge blockade. Both sides tried to force a change in the attitude of the adversaries from the opposite bank of the river. Sipo reports show that: "the inspiration and soul of all the confusion is [...] Lieutenant Albert Battel, [...] implacable and even hostile to the police" .

Destroyed bridge on the San.

A compromise was soon reached at a higher level. In exchange for the withdrawal from the blockade, Jews younger than 35 years old who work for the Wehrmacht and older ones who can identify themselves with a Gestapo stamp were excluded from the deportation.

The SS, of course, did not intend to respect these agreements. After the blockade was released, armed police units surrounded the Jewish quarter. Alarmed by this, Liedtke ordered Battel to bring at least some of his Jewish employees to the Wehrmacht headquarters. He, threatening to use weapons, broke into the ghetto with trucks five times. Each transport brought a new group of people, which was placed in the basement of the commandant's office. Thanks to Samuel Igiela's account, we know that:

On the orders of Lieutenant Battel, the Jews were provided with full bags of biscuits, meat, and even milk was delivered for the children. On his order, we got dinners from the kitchen of the Ortskommandantura.

Battel's heroic revolt had no chance of success . The very next day, the first transports of prisoners set off towards the death camp in Bełżec. Several hundred victims were shot in the forests of nearby Grochowce. Then the ghetto was divided into a zone for working and non-working. Most of the latter group was sent to Auschwitz in September 1943. The last prisoners from the "working" group were murdered in February 1944 in the camps in Szebnie, Stalowa Wola and Płaszów.

The insubordination of the Wehrmacht officer did not go unnoticed in Berlin . However, due to the involvement of all forces in the hostilities and the implementation of the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question," all consequences were postponed until the end of the war. In a note to Martin Bromann, head of the NSDAP chancellery, Heinrich Himmler made a personal commitment to do so.

Destroyed buildings on the San River

Battel himself was unaware of the attention paid to him. Due to poor health, he was discharged from service in 1944 and returned to Wrocław. The end of the war found him in Soviet captivity as a member of the Volkssturm. Then he moved to West Germany. The denazification act deprived him of the right to practice as a lawyer. He died in 1952. The memory of his feat survived thanks to the efforts of the Israeli lawyer Zeev Goshen . Thanks to him, on January 22, 1981, the Yad Vashem Institute posthumously awarded Battel the title of Righteous Among the Nations. On June 24, 1993, thirty-eight years after his death, the same honor befell Max Liedtke.