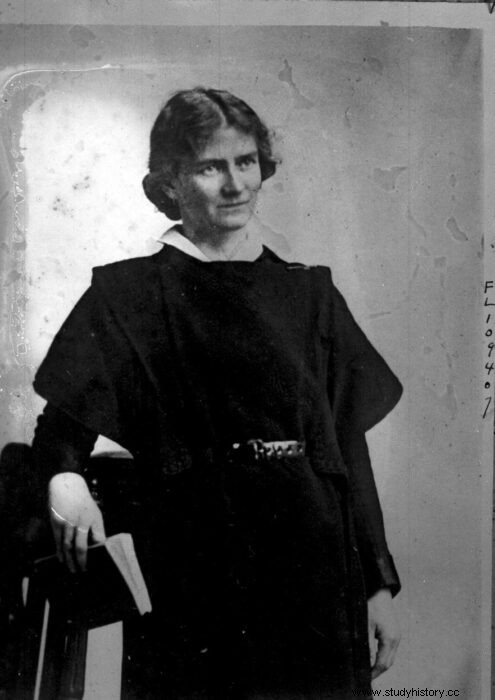

During his fascist dictatorship, four people attempted to assassinate Benito Mussolini. Yet only one person came close. On April 7, 1926, a small figure went out of a crowd in Rome and fired a shot at the infamous dictator. Her story is erased from history, swept under a rug and forgotten. Now, almost a century later, her actions are remembered. Their name is Violet Gibson; and this is her story.

The Early Life of Violet Gibson

Violet Gibson was born into an extremely wealthy Anglo-Irish family in 1876. Her father, Baron Ashbourne, was Lord Chancellor of Ireland, the country's highest legal office. Violet was one of eight children living in the affluent area of Merrion Square in Dublin. A search through the National Archives' census of 1901, shows an overview of the family. Lord and Lady Ashbourne, and five of their children are documented, along with their extensive housekeeping staff. Eleven servants were registered with the family in 1901, indicating the level of prosperity that the family maintained. Violet was a middle child, with two older brothers, Edward and Victor, and two younger sisters, Frances and Constance, who lived at home at the time of the 1901 Consensus.

Violet's Education

The sons were educated in Harrow, Trinity, Oxford and Cambridge, while the daughters were taught by governors. She acquired the title, the Honorable Violet Albina Gibson, at the age of nine, when her father was appointed Lord Chancellor. At the age of eighteen, Violet was a debutant at Queen Victoria's court. The term debutant refers to a young woman being introduced to society, usually from an aristocratic or wealthy background. They would make their debut by training in front of the reigning monarch and participating in the social season, hoping to find a husband or match.

Family Lifestyle

According to the social columns, the Gibson family led a prosperous and luxurious lifestyle. Life on Merrion Square was filled with balls, concerts in London and Dublin, family vacations in France and Italy and skiing in San Moritz. They also attended social events at Buckingham Palace quite regularly. Violet Gibson first visited Italy at the age of ten, with her father. Little did she know that this country would have a major impact on her life.

Illness and childhood

Violet was weakened by illness from a very young age. She developed scarlet fever, pleurisy, rubella and peritonitis, which made her physically fragile and small in growth. She was a young woman with great inner existential energy who had no outlet for expression. As a young woman she had a great interest in religion, politics and philosophy. However, much of her life until then had been spent resting and recovering from illness. At the age of 21, in 1897, she received an independent income from her father and decided to pave her own path in life.

Violet as a young woman

When she received her independent income, Violet began to travel. She explored theosophy and its teachings in France, Germany and Switzerland. Influenced by her brother, Willie, who sympathized with the Irish victims who fought for Home Rule, she fell in love with the idea of social justice. Willie had converted to the Roman Catholic Church while a student at Oxford University. He introduced Violet to Christian socialism and Catholicism, which was committed to the rights of the poor. Fiole's political education and understanding of social justice deepened as she regularly accompanied her brother around the slums of London.

In 1902, at the age of 26, Violet converted to the Catholic Church. When she heard this news, her family was completely devastated. Violet moved to Chelsea, where she explored a bohemian lifestyle. She soon fell in love, and became engaged to an artist. One year later, the fiancé died suddenly. She had recently lost a brother and sister-in-law, and the weight of these losses struck her deeply. Violet turned her life to charity and prayer, and began visiting sacred places in her beloved Italy. She soon became ill with a fever and returned home to England. She moved to Devon, where she often visited Buckfast Abbey, and found peace from grief and met Enid Dinnis, a novelist, who would become her closest friend.

Violet and the outbreak of World War I

Violet was deeply affected by the outbreak of World War I. She was an ardent pacifist and hated violence of any kind. Her brother Victor, whom she was closest to as a child, had been captured in South Africa during the Boer War. He had returned from the horror that had been severely traumatized, and the whole family had been engulfed in terror and grief throughout his imprisonment. As a result, Violet was drastic against war of any kind. During World War I, Violet went to Paris and worked as a peace activist with an anti-war organization. She joined the Women's International Congress and worked with socialist and suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst.

The Rise of Benito Mussolini

The Rise of Benito Mussolini In 1919, Fiole's beloved Italy was in chaos and on the brink of civil war. Benito Mussolini had formed the National Fascist Party, inspired by the support of unemployed war veterans. He coordinated them into paramilitary squadrons known as Blackshirts, which used to terrorize his political opponents. At this time Violet was living alone in Kensington, England, recovering from another illness; flu. As she is withdrawn to recover, her thoughts begin to run wild. Demons rising from the past to haunt her. It is possible that this mental crisis was caused by the sudden death of her beloved brother, Victor. The result of this makes Violet quite angry, which causes her to attack a young girl with a knife in South Kensington.

This attack results in Violet being admitted to an asylum. While engaged, she continues to follow the rise and growth of Mussolini's power in Italy. As bloodshed and the regime of terror continue to flourish, Violet begins to weave a plan. She hires an Irish nurse, Mary McGrath, to come and take care of her when she is released from asylum. They pack their bags and go to Rome, but what Mary does not know is that Violet has packed a small revolver in the suitcase.

Arrival in Rome

In November 1924, when Violet and Mary arrived in Rome, they originally lived in a retirement home, an Italian boarding house, before moving to a convent near Piazza di Spagna. Here Violet had her own room, which gave her more privacy to linger on her plans. She began going on excursions to Rome on her own, and visited Trastevere, a working-class district populated by immigrants. At that time it was considered one of the most dangerous places in the city, and Violet spent a lot of time there among the poor. She joined a group of Catholic socialists who were in opposition to Mussolini and who shared her abhorrence of violence during Mussolini's reign. Violet felt that Mussolini was stepping on, not only the idealized historical Italy that she admired, but also the social and political freedoms that she felt liberal Italy had supported.

Opponent of Mussolini

Being in opposition to Mussolini was playing a dangerous game. Giacomo Matteotti, leader of the United Socialist Party and Mussolini's strongest political competitor, was abducted in June 1924 by a fascist troop on its way to parliament. He was forced into a car, taken to the forest, beaten, sexually assaulted, stabbed and dumped in a ditch. This brutal murder frightened Italian citizens and deeply affected Violet. Her identification with the heinous crime was potentially a key ingredient in the plan that took shape in her mind. A plan to place himself in opposition to Mussolini.

Violet's first attempt at retaliation

Basically, Violet Gison decides to offer herself as a victim of Musolini's crimes and the terrible sins of fascism. In her prayers at the monastery, she kneels before an altar she has made and shoots herself in the chest. She does not succeed, and the bullet passes straight through and lacks some vital organs. Violet is found, lying on the floor in a pool of blood, by a terrified Mary McGrath and a doctor is called immediately. Her family was desperate when they heard the news and wanted to keep the news as quiet as possible. Violet refused to return to England, suspecting that she would again be locked up in an asylum by the family. Instead, she went to a private clinic in Rome and was visited every day by the devoted Mary McGrath.

Two months later, Violet was discharged and spent the night in the convent of Santa Brigida with her faithful companion. At this point, Violet is probably the clearest she's been in years, and comes to the conclusion that the only way to get rid of Mussolini is to get rid of Mussolini. In the spring of 1926, a year and a half after Matteotti's murder, a number of men were put on trial. It was a show trial, their fate had already been decided, but still Violet was seen present, took notes and followed closely the prepared proceedings. Her appearance was an indication that she had not forgotten her plans, or her willingness to carry them out.

Mot Mussolini

Violet fired her loyal companion, Mary McGrath, and sent her back to Ireland so that she could concentrate fully on her plans. It was time to act. On the morning of April 7, 1926, Violet left the convent of Santa Brigida, a small, frail, white-haired figure. She attended Mass in the chapel before going to Via Nomentana, to begin the long journey to the Palazzo Littorio, where the fascist headquarters were located. Benito Mussolini was not to appear there until the afternoon. On the way to the fascist headquarters, however, Violet noticed a crowd gathered at Campidoglio. Upon request, she found to her surprise that they had gathered to see Mussolini. Although this was not part of her original plan, she realized it was time for her to implement the plan.

Violet executes her plan

Violet Gibson pushes her one-legged frame towards the front of the crowd and claims a place in front of the Palazzo dei Conservatori. The place was packed with secret police, and the crowd grew larger by the minute. The worshiping crowds roared when Il Duce appeared, and took to the podium to give a speech for the Royal College of Surgeons. Violet raised her arm slowly, held it steady and aimed. She shot Mussolini in an empty area. But as she did, he turned his head a little towards a student choir that had just broken into the chorus of a fascist hymn. He staggered back, his hands squeezing his face as blood flowed through his fingers. The bullet had missed, passed through part of his nose and bit his cheeks.

Violet, in shock, fired again, but the bullet had been stuck in the chamber. The crowd roared, desperate to avenge their hero. They sat on Violet, before the police saved her from being torn limb from limb. In a letter to his dear friend Enid, Violet described how the police saved her from being violently torn to pieces by the crowd. She also described the feeling of transformation she felt inside, how her heart was filled with happiness and love. Mussolini made a public appearance shortly after the shooting, wearing a bandage over his nose and cheeks. Official statements recorded that he was calm and composed, and drew on the assassination attempt as if it were nothing.

The Aftermath

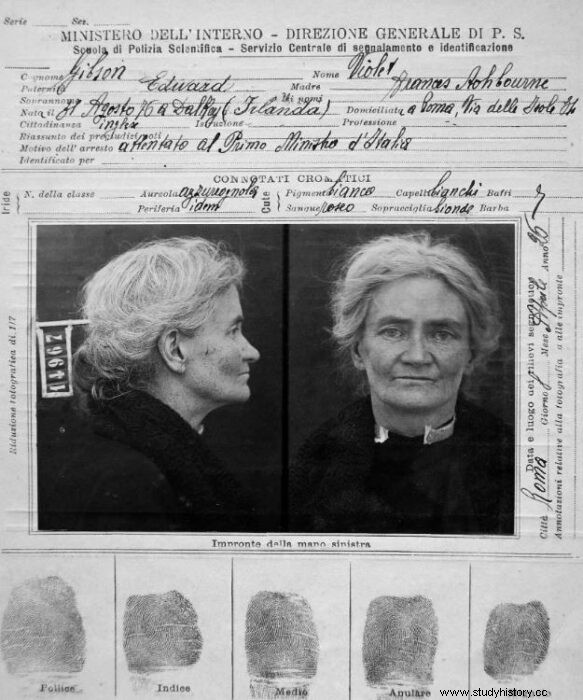

The news of Violet's assassination attempt swept like fire in dry grass throughout Italy. Pope Pius XI announced that all masses that day would be held in honor of Mussolini's miraculous escape and the newspapers read the headline:" Our glorious Il Duce saved" and painted Violet like a mad woman. Black shirts made noise, burned non-fascist printing presses and attacked immigrants and the poor. Letters poured in from leaders around the world expressing their relief at Mussolini's narrow flight. Violet was taken to Regina Coeli Prison, where she was photographed, fingerprinted and striped. She was then taken to the hospital so that the injuries she had received from the violent crowd could be taken care of. After the first interrogation, Violet was reported as calm, clear and collected.

During questioning, Violet Gibson weaved a web of fabricated stories. She claimed that she shot Mussolini for God's glory, that she had communicated with the dead and that they were all her accomplices. The police constantly tried to uncover her motivation, but Violet never gave up. Her family and the British Foreign Office came up with a crazy prayer, claiming that she had been tempted since her brother Victor died. Fiole's fate depended on whether she would stand trial or be declared insane. The psychiatrist's report indicated that she had chronic paranoia and recommended that she be committed to insane asylum.

Purple and the asylum

Thirteen months after the shooting, an agreement was reached with the British Foreign Office. Violet was not allowed to participate in her own trial, as it was feared that she would compromise with the claim of clear madness. The request is approved, and Violet, at this stage, has the impression that she is going home a free woman. Instead, she is beaten on a train in Rome by a group of ordinary policemen and nurses on their way to England. When she arrives, she is taken to Harley Street, where she is examined by two doctors and declared insane. It's close to midnight, when she's taken to Northampton, to be committed to St Andrews, an insane asylum. She was admitted on May 14, 1927.

Violet would be kept here, locked up and locked up, for the next twenty-nine years until she died. She wrote many letters to her family, her friend Enid, but none of them were ever sent. Other friends wrote and tried to reach her, but she never received them. She was kept from the outside world; separately, alone, hidden. She had no visitors except her sister Constance. Violet never gave up the campaign for his release. She wrote letter after letter to bring the authorities' attention to the case, but they were never posted. Everything Violet wanted was to be moved to a Catholic nursing home to live out the rest of her days in peace, but that day never came. On May 2, 1956, Violet died at the age of eighty. There was no public announcement about her death, and no one came to her funeral.

the conclusion

The story of Violet Gibson is one that has been erased from history, hidden in the shadows. She was painted like a crazy woman and locked out of the world. But today her actions are remembered. In 2014, her story was brought to a wider audience by a documentary broadcast by RTE in Ireland. A book has also been written about her life by Frances Stoner-Saunders:'The Woman Who Shot Mussolini'. Furthermore, Dublin City Council has adopted a proposal to put up a plaque dedicated to her in the city, probably outside the childhood home. Councilor Mannix Flynn, who proposed the proposal, declared that Violet Gibson deserved her rightful place in the history of Irish women and in the rich history of the Irish nation.

Related:

Marco Polo, merchant who became the world's greatest explorer