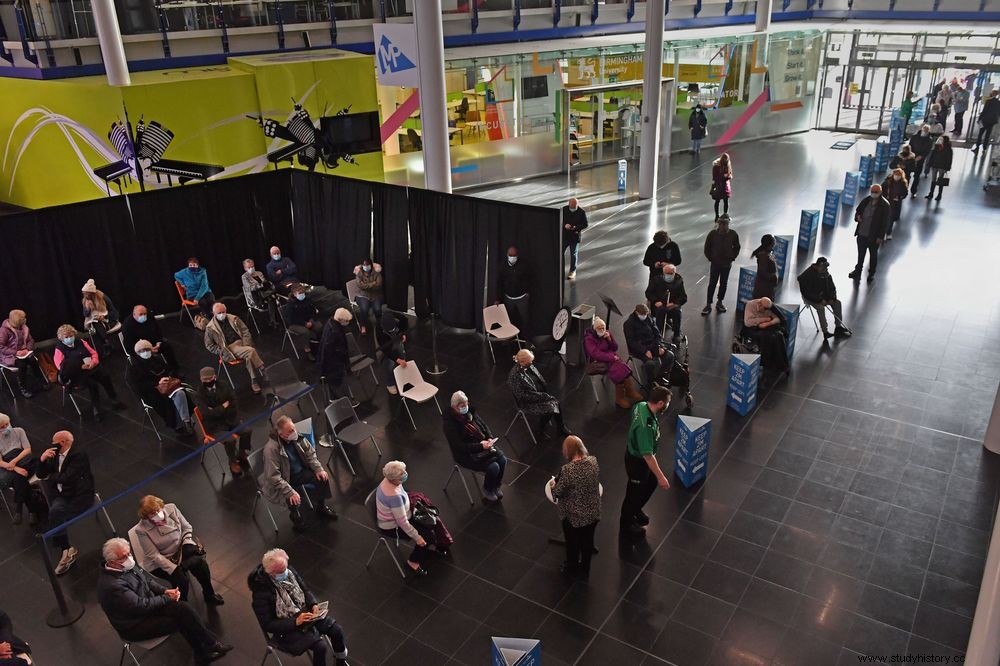

The COVID-19 vaccine widespread vaccination gives the world a chance to expect normality. For more than 15 months, the public has been waiting for news about the vaccine. With the increasing death rate, it was not an easy task to ensure that the vaccine would be as effective as it had to be.

Many vaccines protect people against various diseases. The very first vaccine introduced a learning curve. From that moment, scientists, doctors and virologists continue to produce the most effective and safest version of a vaccine. It is through the evolving work of the past that paved the way.

The first vaccination tried to stop the spread of smallpox. From the beginning of the 10s, the predominant disease was affecting the majority of the population. Even in a time without medical machinery, however, certain findings in disease prevention put a start.

In the 16th century, China and India found ways to prevent the spread of smallpox. The first was grinding smallpox from the infected, blowing the crushed substance into a nostril:the right nostril for boys and the left nostril for girls.

The second method paved the way for modern vaccinations. Variolation, scraping the matter from a copper wound in the skin. In addition, Africa and Turkey practiced this method, and soon, Europe and America. Although it was registered in the 16th century, there is speculation that the method has existed since 200 BC

Here are the origin stories of some of the vaccines we know today.

Edward Jenner - Vaccine against smallpox (1796)

What are cups?

Smallpox, a life-threatening and contagious disease, causes pus-filled blisters to form all over the body. The origin is unknown. However, it dates back to 10,000 BC, when the first agricultural settlements took place in northeastern Africa. The spread of the disease may have been through Egyptian merchants and spread to India.

The vaccine

Known as the 'father of vaccines', Jenner's scientific approach to vaccinations showed the effectiveness of variation.

Jenner's hypothesis was that copper infection could protect humans from smallpox.

Although it is an uncommon disease in cattle, smallpox is the expensive variety of smallpox. It spreads to humans through the cows. Blisters formed on the hands of the dairy workers as they handled an infected cow.

In May 1796, Jenner took the case from a blister of a milkmaid infected with copper. He scratched the case on the arm of an eight-year-old boy. After having a reaction and feeling sick for a few days, the boy recovered completely.

In July 1796, Jenner scratched the eight-year-old boy in the arm with matter from a fresh cup wound. The boy remained healthy and showed no signs of infection.

Transferred to a human chain, cowpox provided protection. That's why the world had its first vaccination.

However, many saw using a sick animal to cure humans as disgusting and wicked, which resulted in Jenner being ridiculed. On the other hand, the proven benefits and protection of the vaccine led to a widespread need for it.

From 1977, with smallpox being considered extinct, the vaccine is no longer recommended.

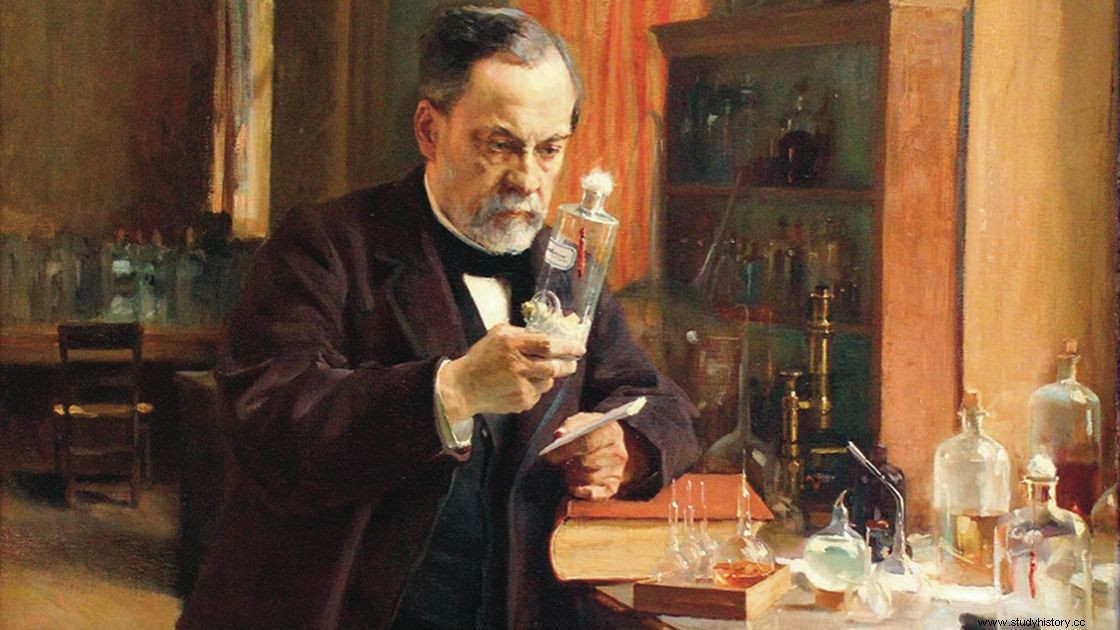

Louis Pateur - Anthrax (1881) and Rabbies (1885) Vaccines

What is anthrax?

A rare but serious disease, anthrax is a disease that mainly infects animals. Humans contracted the disease through contact with the infected animals or contaminated animal products. There is no evidence that it is contagious. However, there is a possibility that the skin lesions are through direct contact.

Although rare, it is a disease of great concern. In the United States, bioterrorism attacks involve arming anthrax.

The vaccine

Pastuer, a French biologist, realized that attenuated virus strains can fight disease.

His early work involved chickens. Wanting to record the fatal development of bird cholera, he left cultures of the virus in his laboratory and went on vacation. His assistant was to inject the chickens with the fresh cultures before he left. However, the assistant forgot to do so only after returning from vacation.

The chickens, with delayed injection of the cultures, did not get bird cholera. After this discovery, Pastuer injected the chickens with a fresh strain, and again they remained uninfected. The most important factor that was discovered was that oxygen weakened the virus, and thus the first laboratory vaccine.

With that discovery, he focused on the disease that mainly affected cattle at the time:anthrax. Many attempts to develop a vaccine by other researchers ended in failure. Methods of killing or weakening the virus only resulted in more deaths.

Pasteur anthrax bacillus was discovered can not be easily weakened by oxygen. More spores would just form. In 1881 he found that growing spores at 42˚C / 180˚F made them incapable of producing spores. They needed heat and oxygen to be artificially weakened, not killed.

The public experiment

In his famous public experiment, Pasteur used two groups of animals. He vaccinated the first group, but not the second. After two weeks, he injected all the animals with live anthrax cultures. The vaccinated survived. The unvaccinated died or died in front of an audience.

The results showed that Pasteur's contribution revolutionized the work of combating infectious diseases.

What is rabies?

A viral, but preventable, disease transmitted through the bite of a rabid animal. Rabies affects the animal's central nervous system, resulting in brain disease and unavoidable death.

For humans, it attacks the brain and spinal cord and awakens them. When it reaches the spinal cord, the result is often death. Life expectancy for a human after the onset of symptoms is seven days.

The vaccine

There were problems studying the virus. The onset of the infection, with signs of the disease, varied.

Pasteur's first step involved selecting the most deadly, fast-acting strain of the virus. He then injected the virus into a rabbit brain.

His protégé, Emile Roux, kept a suspended piece of a rabbit's infected spinal cord in a flask.

Pasteur determined that drying of the infected tissue weakened the virus. This was shown in his experiments on dogs with debilitating infections. These experiments were dangerous, with samples taken from rabid animals.

After the success of the dogs, he began inoculating humans.

All human trials were successful, but one because the vaccine was administered too late.

In July 1885, Pasteur gave the vaccine to a nine-year-old boy after an attack by a rabid dog. The boy survived and avoided contracting a fatal infection. This worked strongly in favor of Pasteur, as he was not a licensed physician. He was prosecuted if the vaccine failed. With legality forgotten, he became a national hero.

Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering - Whooping cough vaccine

What is whooping cough?

whooping cough is a highly contagious respiratory disease that affects the lungs and respiratory tract. It causes uncontrollable and violent coughing, which makes it difficult to breathe. Especially infects babies and young children, it can make them very sick.

It was the deadliest childhood disease of the early 20th century.

The vaccine

Two former teachers, who became researchers, asked infected children to cough on prepared dishes. The agar gel captured small spots of bacteria.

With children's high rate of infection in the 1930s, America also suffered from the Great Depression.

Kendrick and Eldering saved and studied the cultures in all possible ways. Scientific funding was scarce. They used state resources as well as local and federal funding.

They spent years in the laboratory and provided standardized diagnostic tools, as well as vaccines made from the weakened bacterial strain. Furthermore, they had the first successful controlled clinical study. In addition, they participated internationally to standardize and dispense the vaccine.

This proved to be a promising path for groundbreaking results.

Emil Von Behring - Diphtheria (1926) and Tetatnus (1938) Vaccines

What is diphtheria?

Diphtheria is a bacterial strain that leads to difficulty breathing, heart failure, paralysis and in some cases death. The bacterial strains target the mucous membranes of the nose and throat.

What is tetanus?

Tetanus is a bacterial infection that invades the body. It produces a toxin that attacks the nervous system and causes muscle contractions. It often causes a person's neck and jaw muscles to lock, making it difficult for them to open and swallow. Hence the alternative name 'lockjaw'.

The vaccines

Together with Dr Kitasato Shibasaburō, Von Behring published an article on the development of 'antitoxins' against diphtheria and tetanus.

Toxins were injected into guinea pigs, goats and horses, as well as rats and mice. The animals developed an immunity to these viruses. Rats and mice had a remarkable reaction to diphtheria. Their blood had a devastating effect on the bacteria.

In the case of patients and the diphtheria vaccine, there was a blood transfusion with the animal's blood. However, these patients died immediately. After a change in the production and quantification of the antitoxins, the treatments proved to be successful.

With the tetanus vaccine, a weakened version (active immune) of the disease was inserted into the bloodstream. The discovery and production of an inactive vaccine (bacterial strain killed) was in 1924. Production of a more effective version of it in 1938 proved successful for soldiers in WWII.

In 1948, a mixture of the Diphteria vaccine, the Tetanus vaccine and the Pertussis vaccine created the DTP vaccine.

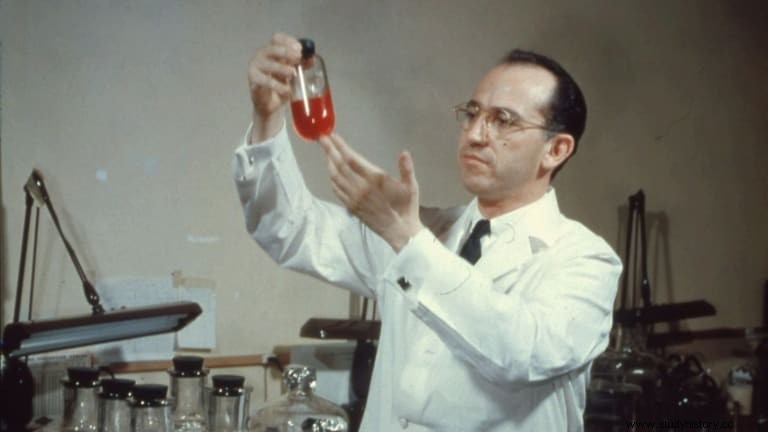

Jonas Salk - Poliovirus Vaccine (1955)

What is Polio?

Polio, a contagious disease, causes nerve damage. This leads to paralysis, difficulty breathing and often death. The majority of those infected are not aware of the infection. The first sign of infection is flu-like symptoms, and therefore it is difficult to assess early detection.

The vaccine

Salk chose the inactive immune method to make the vaccine. He killed several strains of the virus and injected benign strains into the blood of a healthy person. As before, the immune system would make antibodies designed to resist future infections.

In 1954, the vaccine was tested on the 'polio pioneers', who were one million children.

In 1955, the vaccine proved to be effective and safe. Therefore, after the announcement, it was time for a nationwide campaign.

The tragedy struck, however. From Cutter Laboratories, 200,000 people received a defective vaccine. The batches of the vaccine contained live, active strains of poliovirus. 200 children were paralyzed and 10 died. Although this was defective, there was not a single case related to Salk's vaccine.

Even with a delay in production, the number of cases decreased during the first year after the vaccine was available.

In 1962, an oral vaccination of Albert Sobin helped with vaccine distribution.

In 2000, the poliovirus was no longer considered a threat due to the success of the vaccines. Therefore, it is no longer recommended.

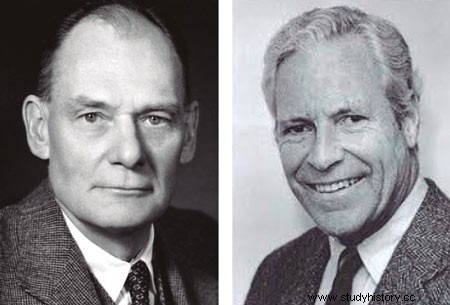

John Enders and Thomas Peebles - Measles Vaccine (1963)

What are measles?

A contagious respiratory infection, measles causes skin rashes all over the body, as well as flu-like symptoms. If left untreated, it can lead to possible life-threatening complications, such as lung and brain infections.

The vaccine

When I asked Enders, Peebles started isolating the virus that was responsible for measles. He collected blood samples and throat swabs from sick students during an outbreak in Boston, Massachusetts. The isolation of the trunk was from the blood of a 13-year-old boy. The spot, named after him as the Edmonston B strain, was actively immune.

Maurice Hilleman - Mumps Vaccine (1967)

What is kusma?

Mumps is a contagious disease, known for its attack on the salivary glands on either side of your face, and behind and under your ears. The most noticeable effect is swelling in the salivary glands.

The vaccine

In 1963, Hilleman's daughter, Jeryl Lynn, came down with a mug. He grew material from her and used it as a basis for the mumps vaccine. He chose the method that is actively immune, and weakened the load. Known as 'Jeryl Lynn Strain', and is still used today.

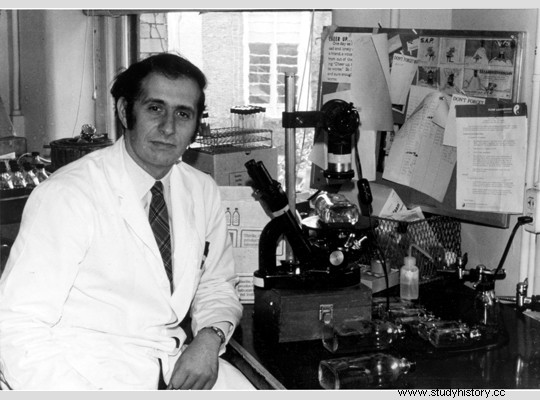

Stanley Plotkin - Rubella Vaccine (1969)

What is Rubella?

Also known as German measles, this contagious, viral infection is known for its obvious red rash. Although there are mild or no symptoms, rubella poses a threat to unborn babies during pregnancy.

The vaccine

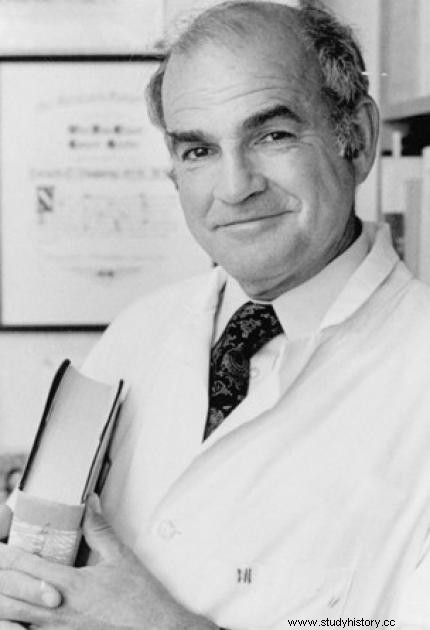

Plotkin used the aborted fetus instead of swab specimens from the patient's neck. The sore throats can be easily contaminated by other diseases.

He collected and studied dozens of aborted fetuses. However, it was the kidney tissue of the 27th studied fetus that produced the strain. This strain developed into a weaker version of rubella, which resulted in the rubella vaccine.

It became known as RA 27/3: R ubella A bortus , after 27 the fetus studied, and the third ( 3 rd) organ harvested.

Maurice Hilleman and colleagues - MMR

MMR is an acronym for measles, mumps and rubella. This is a mixture of the attenuated viruses of the three diseases.

Although John Enders and Thomas Peebles developed the measles vaccine, Hilleman developed it further in 1963, with an improved version available in 1987.

As for the rubella vaccine, he created a variant of the vaccine in 1969. However, he used Plotkin's vaccine in MMR. Plotkin used fetal cells while Hilleman used animal cells. Fetal cells are better equipped to protect people with fewer side effects.

The combination of antibodies does not protect humans in a new way, but in a more practical way. The specific antibodies fight their individual diseases. It gives the immune system an opportunity to develop its defenses against weaker versions of the virus, and prepare it for encounters with the full strength of the virus.

Baruch Blumberg - Hepatitis B Vaccine (1981)

What is hepatitis B?

A sexually transmitted disease (STD), Hepatitis B. attacks the liver. It causes liver damage, liver failure, liver cancer and sometimes death.

The vaccine

The hepatitis B vaccine is the first vaccine against cancer, which helps prevent liver cancer.

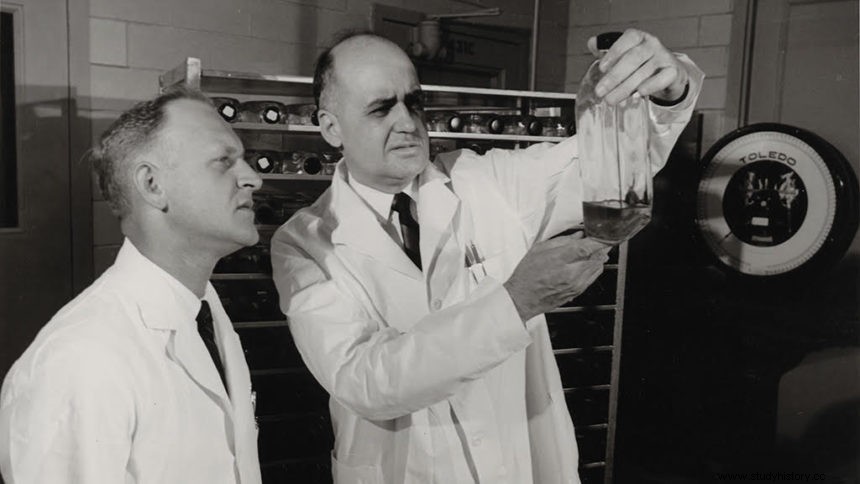

With microbiologist Irving Millman, Baruch was able to develop a blood sample for hepatitis B. With the virus strain obtained, it faced heat treatment. This helped to separate the surface protein from the virus, and helped to make the vaccine. The antibodies were immunized directly from the blood of the carriers.

Michiaki Takahashi - Varicella (Chickenpox) Vaccine (1996)

What is Varicella?

Varicella, or chickenpox, is a contagious disease that causes itchy rashes. Like blisters, they first appear on the chest, back and face before spreading throughout the body in hundreds.

The vaccine

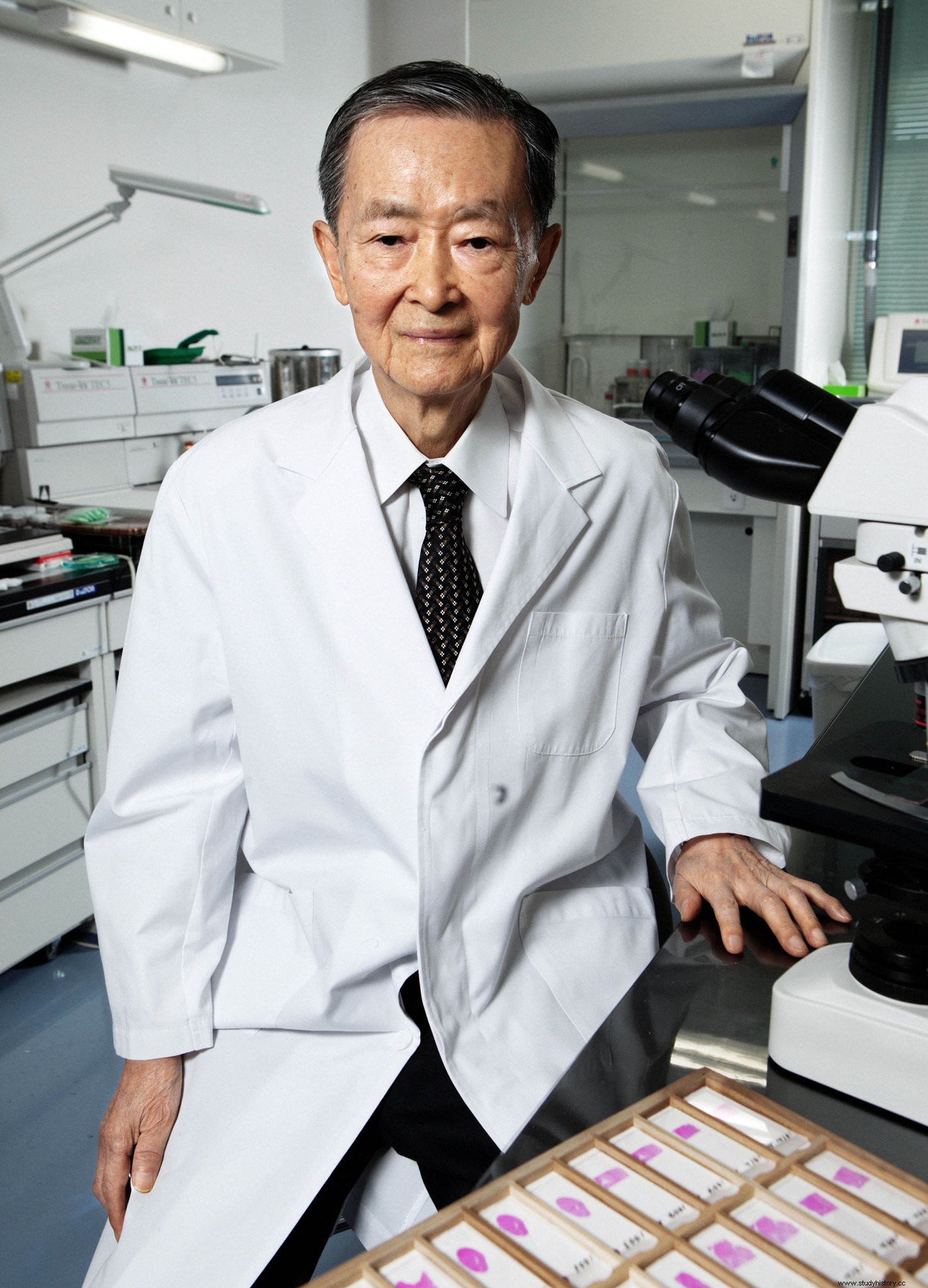

Takahashi probably weakened a load of chickenpox sister virus, which makes it actively immune. The strain was from blisters of a three-year-old with a typical chickenpox disease, named "Oka Strain" after the family.

Guinea pig embryo cultures cultivated the Oka strain. Children then received the vaccine during Japan's chickenpox epidemic. The effect of the vaccine proved to be difficult as certain side effects were similar to chickenpox. The vaccine may have either been ineffective or worsened the condition of the children.

To prove its effectiveness, 16 children with kidney disease received the vaccine. There were no signs of side effects, and the presence of the antibodies will protect the children from the infection.

In addition, researchers further developed the vaccine. They cultured the virus on cell lines from lung tissue of an aborted fetal embryo.

The varicella vaccine became part of the MMR vaccine and became the MMRV vaccine.

Paul Offit - Rotavirus Vaccine (1998 and 2005)

What is Rotavirus?

Especially infects young children, rotavirus is a highly contagious and easily transmitted infection. It causes severe diarrhea and vomiting in infants with young children, often resulting in dehydration and hospitalization.

The vaccine

Offit spent 25 years developing the vaccine.

In 1979, as a child resident, a nine-month-old infant died of Rotavirus dehydration under his care. This case led him to find a vaccine to prevent another.

With the strain found, they chose the active immune method and weakened it.

Although this was in effect, another vaccine to combat Rotavirus was available. Rotashield vaccines were released in 1998. Unfortunately, this vaccine was withdrawn in 1999. It may have contributed to the spread of the virus and increased risk.

In the early 2000s, Rotarix and RotaTeq (Offits vaccine) were made available.

Significance in Anthropology

Through the cultural and medical practices of the past, modern medical professionals created modern vaccines. While fighting against ridicule and criticism for their methods, scientists, doctors and virologists from recent years have dedicated themselves to saving lives. As before, they continue to do so today.

As more vaccinations are created, they develop further. Improvements in composition have a greater effect on the human body. Many people are skeptical about the use of vaccines, just as some were before. However, one must remember that the vaccinations faced a trial-and-error process. It is through past trials and failures that medical professions know how to improve, just as before.

In August 2021, 40% of the world's population (3,119,960,996 people) received their first dose of COVID-19 vaccine. 27.3% of the world's population (2,126,427,265 people) are fully vaccinated.

"The doctor should not treat the disease, but the people who suffer from it."

- Moses Maimonides.