Theoxenia :The Divine Dinner Guest

In Stranger in a Strange Land Part XNUMX:Greece and America , I discussed the Greek concept of xenia. In short, Xenia refers to a host's obligation to a stranger, namely food, lodging and gifts. A form of paranoia reinforced this practice - the fear that your guest is actually a god in disguise. There's even a name for it: teoxeni.

Much like Greece was not (as explained in the mentioned article) the only culture that practiced Xenia , other cultures carry their own stories of theoxenia. Often these guests are judges, who test human virtue by their generosity and kindness towards strangers. The angels who visited Sodom and Gomorrah are examples. Sometimes, however, the motives are more self-centered than that. Sometimes gods slip into human form of lust or as a joke.

Whatever the reason, it provides some fascinating reading. This is a selection of stories about theoxenia , or godly disguise, taken from all over the world, along with some observations about what they have in common.

Virtue Test

In the years before institutional justice systems (any form of them we would at least recognize), people invoked the gods, and stories about them promoted desirable behavior in society. Regardless of one's personal belief in gods and their power, they were useful social tools.

While the Christian God is an all-seeing enforcer of good manners, but polytheistic religions had more human size. A Christian says, "God is watching and he is everywhere." A Greek can not say the same about Zeus, the protector of strangers.

So the idea that a god can hide anywhere and look at you without your knowledge becomes a common remedy for the same goal.

Greek Mythology:Introduction to Baucis and Philemon

Such a story belongs to the Roman poet Ovid. In his Metamorphoses , he writes about Baucis and Philemon.

Hermes and Zeus decide for unknown reasons to become itinerant hikers in Phrygia, a region in present-day Turkey. They travel from door to door for accommodation without success. "All doors [are] bolted / and no kindness given." Eventually, they stumble upon Baucis and Philemon, an old, distressed couple.

No question, they invite the gods in and pamper them. They pull out the tablecloth they reserve for holidays, cabbage, bacon, plums and wine. Based on the hut's humble blanket and ragged linen, Baucis and Phileomon have to take care of everything in the pantry.

Because of one detail, they realize that their new friends are not just travelers:no matter how much wine the four drink, it never runs out. Immediately they fall over themselves to find a suitable victim, and apologize for their simple home and food. They chase their prize goose around the room, but the goose survives its old legs and flees to Zeus and Hermes.

"Let the same hour take us both"

The gods command Baucis and Philemon to stop, and they actually compliment the two for their generosity. They ask them to follow them to a nearby mountain, where they will retaliate against their evil neighbors.

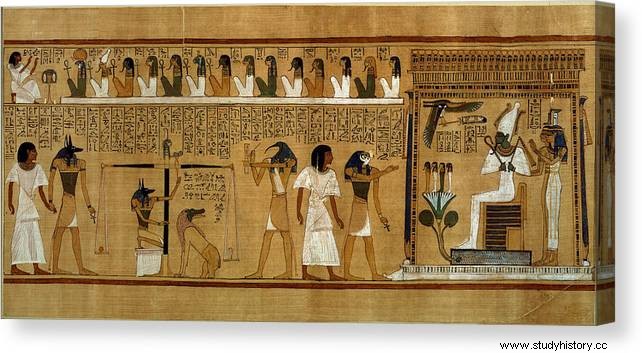

From the top, Zeus and Hermes flood the valley below. Big-hearted Baucis and Philemon weep over their friends, as wicked as they were. But when the water sinks, their grief turns to awe. Their house has been transformed. «Where the frame was first made, marble poles / columns glittered, and the blanket shone golden in the sun, and legends carved out / adorned the doors. And the whole ground shone white with marble. " Their house is now a temple.

The gods turn to them and ask, "Tell us now, good old man and you his wife / worthy and faithful, what is your desire?" This is an extension of ancient Greek guest rituals. At the end of a visit, the host exchanged gifts and strangers.

Philemon first gathers his wife's counsel, and then requests that they be appointed caretakers of the new temple for the rest of the days. And, he adds, let the same hour take them both. Let them die without seeing the grave of their beloved or laying the ground over it.

And so it was.

Hinduism:Krishna, the wealthy family and the poor widow

In Hinduism, Krishna is one of its most revered deities. He is the eighth avatar of the god Vishnu, just one face that the four-armed deity assumes. There is thus an absurdity in the idea that Krishna pretends to be someone else. It's like wearing a mask on top of a mask.

The following is taken from a passage by Swami Tyagananda in the book Hosting the Stranger:Between Religions (pages 148-149).

Krishna and her friend Arjuna travel as wandering fat people, healers who live on the road and survive on alms from patients. They meet a wealthy family. The family is happy to offer shelter and food that matches their standard of living. As a parting gift, Krishna blesses them with continued prosperity and material abundance

After traveling on, they meet a poor widow. Her only asset is a sick cow. She shows similar warmth, but she is only able to offer the god a glass of milk. As a farewell gift, Krishna tells her that her cow will soon die.

When they are back on the road, Arjuna Krishna apologizes. He's terrified. Why did Krishna give abundance to an already prosperous household, and then curse an old woman with loss of livelihood?

Krishna replies:“My wealthy host is insanely attached to his wealth and reputation; he has a long way to go before he is spiritually awakened. On the other hand, this poor devotee is already well on the spiritual path. The only thing that separates her from the highest freedom is her attachment to the cow. I removed the obstacle from her path. "

For the sake of desire

A recurring theme for godly disguise is romance. From time to time the gods mortally see that they want and use a more humble persona to achieve them.

Greek mythology:Zeus and his many paramourThe king of the Greek gods is notorious for his attempts at mortals. The jealousy of his wife, Hera, forces him to be. . . resourceful. Sometimes he becomes a man. Sometimes he turns into an animal:he seduces Leda like a swan and Europe like a white bull.

Zeus' high libido is not just a joke among classics. Zeus himself is characterized as very conscious, and it was probably a common source of comedy among Greeks. For example, in Homeric hymns, Zeus forces Aphrodite to fall in love with the mortal Anchises. Aphrodite has beaten Zeus with lust so many times that Zeus wants revenge. Of course, the link ends badly, but that's a tragedy for another article.

Zeus and the Alcmene

A good example of Zeus' sense is his experiment with the Alcmene, a princess of the Mycenaeans, a kingdom south of present-day Greece. This special version of that affair comes from the Library a collection of Greek myths from the second century AD

Alcmene is a princess in exile. Her father, Electryon, planned to wage war on Teleboans to avenge his brother's death. For safekeeping, he entrusted his kingdom and the daughter of the warrior Amphitryon. While Amphitryon and Electryon herd cattle for Amphitryon's care, they teased an ox. The bull accused. Amphitryon threw his club. The club came back and beat Electryon and killed him. Amphitryon fled the country with the Alcmene in tow. It's one of those moments in the myth that borders on parody.

So Amphitryon seeks refuge in the nearby city of Thebes, but he does not stay there long. As a matter of honor for his dead father-in-law, he decides to wage war on the Teleboans, the people Electryon had intended to fight. He leaves the Alcmene in Thebes.

Zeus assumes the form of the absent Amphitryon. For three nights he lays the Alcmene. He can't keep it a secret for long. Amphitryon discovers the list when he returns, and Aclmene is not overjoyed to see her husband for long. From her perspective, he never left.

The Alcmen's affair will be something of a blessing in the long run. Zeus gave her a special child named Heracles.

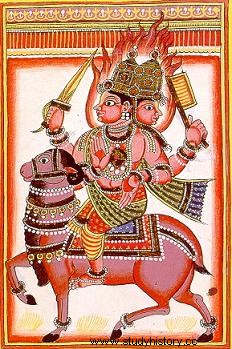

Hinduism:Agni and Mahabharata

The Hindu fire god, as far as I know, does not have the same struggle with his passions. Yet he has a similar episode in Mahabharata (page 711).

To understand this story, it is important to note the role of fire in Hinduism. In short, lighting a ritual fire was a way to communicate with Agni, the Vedic god of fire.

In the kingdom of Mahishmati and under King Nila's rule, such a fire develops a strangely sensuous relationship with a princess. King Nila's daughter, whose name is never mentioned, is the only one who can fit it. "Even when it was waved, it would not flare up until it was aroused by the gentle breath of the girl's bright lips." She may be under the impression that it's just a fire, but the god Agni actually steals kisses.

Insanely in love, Agni decides to propose to her. He takes the form of a Brahmana, a priest, to woo her. Unfortunately, the king discovers them while they are traveling. He calls for the guards and intends to punish Agni. Furious, Agni reveals her true, burning form. The king is humble about the greatness of the god and asks for forgiveness.

Trickster gods

The last type of teoxeni the story involves luring gods, who cast on facades because of their nature.

The Norse god Loki

Marvel's interpretation of Norse folklore leaves much to be desired at times. Its ideas about Thor, Odin, Loki and the different inhabitants of Nordic cosmology are high on science fiction and short on the original's wonders and magic. Nevertheless, the depiction of the deceiving god Loki is accurate. Like his comic book counterpart, Loki is an ambivalent force, neither good nor evil, and can change form at will.

That gift resulted in Baldur's death, the god of light.

Loki and Baldur

Baldur's mother Frigg, the queen of the gods and Odin's wife, loves her son dearly. In fact, so much so that she travels to every corner of the nine kingdoms to demand one promise from everything, living and uninhabited. Promised:you will not hurt my son. This does not prove to be a challenge. Baldur is loving and well loved.

Her mission completed, the gods celebrate with drinking and partying. So, deep inside a drink-induced stupor, they decide to have fun. They throw random objects at Baldur to test Frigg's oath. Sure, everything from arrow to ax refuses to hurt Baldur.

A god who is exposed to petty jealousy, Loki interferes. He turns into an old crown and asks Frigg and asks if she has left anyone out of the lawyer list. In fact, she had. She considers the herb mistletoe too harmless to be worth the trouble.

Loki then approaches Hod, the god of darkness. Hod stews in a corner while the other gods enjoy themselves. He's blind, so he can not throw anything. Loki tells Hod that he wants to help and act as his vision. He steers Hod into position, lining up the shot. . . and puts mistletoe in the hand of the blind god. Hod lets fly. Baldur collapses, killed by the one thing in the universe that Frigg considered too small to ask.

The gods moan. Frigg despairs. But it is a glimmer of hope. Hel, the goddess of the underworld, makes a deal with Frigg:If every living creature sheds tears for Baldur, Hel will free him.

And the tears flow from every creature, except one:the giantess Thok, who is actually Loki in disguise.

It was the end of the god of light.

Myths from Asia: kitsuneSeveral cultures in Asia do not have their own Loki per se , but rather a whole species of Lokis. This is the cause of many headaches in the myth, as you can imagine. Kitsune - the Japanese words for these deformed fox spirits - are morally gray in character. Sometimes they deceive others, but they can also give wisdom or even tenderness. In the story of Old Man Wu-cheng , for example a kitsune advises and guards a bureaucrat throughout his career.

Observations:The Hypocrisy of the Gods

Two of the above categories, desire and virtue, present a paradox. Gods inhabit the role of unscrupulous figures and moral guides. For Baucis and Philemon, Zeus is a protector of the alien and rewards justice. To Alcmen's husband, he is morally degenerate (infidelity was as scandalous then as it is now). This leads us to ask what the followers of Zeus really thought about their gods.

For these religions, the best approach to the relationship between followers and their gods is that of a serf and a liegeherre. Like a baron or a king, such gods have greater power than the mortal men beneath them, but they possess the mental frailties and impulsiveness of a mortal. The troublesome "problem of evil" is not a problem because, well, the gods are human-sized figures.As a baron or king, they are also the law of the land and someone with whom a serf wants a good relationship.

Stories about them are like speculations about the royal class, like Don Giovanni or King Lear or even the Crown. Sometimes they were accurate and had to be taken seriously, and sometimes they were just gossip told for entertainment.

A mother culture

The similarities between many of these stories and their broader categories may be due to a shared origin.

Like amoebae, language mutates. For example, French and Spanish are called "romantic" languages because they come from Latin, from Rome. Latin itself has its own ancestry, which can be traced to a language group called Proto-Indo-European. Among the other descendants of proto-Indo-European is Sanskrit (the language of Hindu texts), the West Germanic language of Norse, Greek and English.

After this, it is believed that cultures derived from this mother tongue shared more than language. Based on that assumption, experts are trying to reconstruct not only the mother tongue itself, but also the religion and myths of the original culture. For example, Zeus and Agni may be copies derived from an older proto-Indo-European god.

However, there is a significant zeal to choose. People (and nature) are good at coming up with the same idea independently. This is a common problem that goes by many names. In science it is called "several discoveries." In biology it is called "convergent evolution." It is therefore difficult to determine whether myths originated from a common source or developed on their own.

The lack of older written texts further complicates the matter. The proof I gave Stranger in a Strange Country is complete due to clear historical documentation. A hypothetical mother culture, on the other hand, would be decidedly pre-literate. Even worse, that culture would have risen, fallen and been forgotten long before it came into contact with a literary society. The Norse (eg early Swedes, Finns, etc.) had no written chronicles of their own, but Christians wrote down their myths as a curiosity. As for proto-Indo-Europeans, neither they nor their neighbors were literate.

Ultimately, it is a knot for archaeologists to untie. Without documentation, we look at evidence.

the conclusion

Aside from the more difficult aspects of historical interpretation, I hope you enjoyed this trip to the myth. Although they no longer represent the sacred, myths are a way of wonder to enter our own lives. Although they lack the sophistication of novels, TV series and movies, they have a sincerity and innocence that can not be recreated. They make water for wine, straw for gold and travelers for gods.