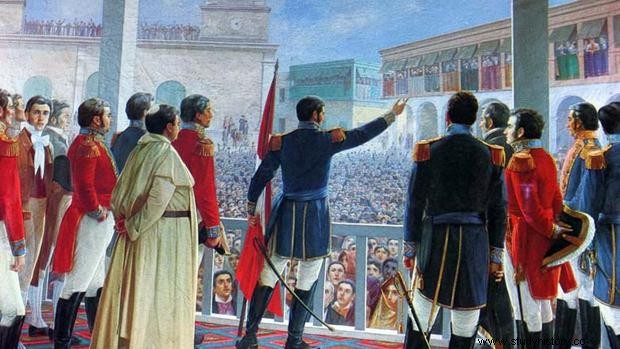

San Martín proclaims the independence of Peru in 1821., by Juan Lepiani A military boy who became a liberator José de San Martín was born in Yapeyú, today Argentina, on February 25, 1778, into a family with a military tradition. The father, a middle-class Spanish hidalgo, served as captain and senior assistant of the Infantry Assembly of Buenos Aires until, in 1774, he was appointed lieutenant governor of the department of Yapeyú, a Jesuit mission on the banks of the Uruguay River orphaned by power after expulsion of the order. Likewise, the liberator's mother was also Spanish and from a prominent family, Gregoria Matorras del Ser, first cousin of the governor and captain general of Tucumán. Precisely two of the five children of the marriage, including José, were born while stationed as a lieutenant there. His first playmates were Guarani Indians. Although, the couple moved to Spain in April 1784, where José was going to make contact with the Spanish Army that his father loved so much.

San Martín proclaims the independence of Peru in 1821., by Juan Lepiani A military boy who became a liberator José de San Martín was born in Yapeyú, today Argentina, on February 25, 1778, into a family with a military tradition. The father, a middle-class Spanish hidalgo, served as captain and senior assistant of the Infantry Assembly of Buenos Aires until, in 1774, he was appointed lieutenant governor of the department of Yapeyú, a Jesuit mission on the banks of the Uruguay River orphaned by power after expulsion of the order. Likewise, the liberator's mother was also Spanish and from a prominent family, Gregoria Matorras del Ser, first cousin of the governor and captain general of Tucumán. Precisely two of the five children of the marriage, including José, were born while stationed as a lieutenant there. His first playmates were Guarani Indians. Although, the couple moved to Spain in April 1784, where José was going to make contact with the Spanish Army that his father loved so much.The Creole began his studies at the Royal Seminary of Nobles in Madrid, a place of training for the children of the nobles and the military, although other sources rule out that he went through this elite school. To enter it was necessary "to prove to be sonsdalgo notorious according to the laws of Castile, clean of blood and of mechanical trades by both lines". What is certain is that on July 21, 1789, at the age of eleven, José de San Martín began his military career as a cadet in the Murcia Regiment, where he entered claiming to be the son of a captain. His military career began in the battles against the Moors in Melilla and Orán. When he was still a young beardless soldier he was added to the artillery battery of Captain Luis Daoiz, later one of the heroes of Dos de Mayo in Madrid. . Before the War of Independence, the young Creole had already fought against the French in the Pyrenees and against the Portuguese in the War of the Oranges (1802). In a recruitment mission he was seriously injured by some thugs who tried to take a suitcase with three thousand reals of fleece, an amount from the militia. All this without forgetting his time on the frigate Santa Dorotea, which formed a squad in the Mediterranean against the Barbary corsairs . During this naval period he met Napoleon in Toulon, when he was sent on behalf of "La Dorotea". The fact that the emperor greeted him influenced the admiration that San Martín always professed for the Corsican as a genius of war. In 1804, his promotion to Second Captain at the age of 27 forced him to change units. In the “Campo Mayor Volunteers” battalion, which was in Cádiz, he met General Francisco María Solano Ortiz de Rosas, Marquis of Socorro. They were both Americans. Solano, a man of liberal ideas, warmly and sympathetically welcomed his young compatriot whom he helped and advised from experience. And both shared a pessimistic view of the future of Spain and her government in the American territories. They both felt that the Motherland was teetering on his feet.

The Surrender of Bailén- Prado Museum In the midst of the Napoleonic invasion, Solano died during a popular uprising against the seat of government when he was accused of collusion with the French. San Martín, a man of order, tried to defend his friend and his superior from the tumult, which also almost cost him his life. Disorder, regardless of its color, displeased the rigorous Creole. The disasters that the French invasion brought would divert San Martín's military career. The Central Board of Government, established against the Napoleonic government, promoted the Creole to the position of First Captain in General Castaños's regiment, "the Bourbon Cavalry." In this unit he participated in the battle of Bailén on July 19, 1808. The first major defeat of Napoleon's troops resulted in San Martín being promoted to cavalry lieutenant colonel on August 11, 1808. He also participated in the Battle of La Albuera, the finishing touch to a two-decade career in the service of the Spanish Army, under the command of English General William Carr Beresford. Precisely the multinational character of the anti-Napoleonic forces put him in contact with the British liberal and revolutionary circles that would contribute so much to American independence. His long stay in Cádiz strengthened that liberal mentality for years.

The Surrender of Bailén- Prado Museum In the midst of the Napoleonic invasion, Solano died during a popular uprising against the seat of government when he was accused of collusion with the French. San Martín, a man of order, tried to defend his friend and his superior from the tumult, which also almost cost him his life. Disorder, regardless of its color, displeased the rigorous Creole. The disasters that the French invasion brought would divert San Martín's military career. The Central Board of Government, established against the Napoleonic government, promoted the Creole to the position of First Captain in General Castaños's regiment, "the Bourbon Cavalry." In this unit he participated in the battle of Bailén on July 19, 1808. The first major defeat of Napoleon's troops resulted in San Martín being promoted to cavalry lieutenant colonel on August 11, 1808. He also participated in the Battle of La Albuera, the finishing touch to a two-decade career in the service of the Spanish Army, under the command of English General William Carr Beresford. Precisely the multinational character of the anti-Napoleonic forces put him in contact with the British liberal and revolutionary circles that would contribute so much to American independence. His long stay in Cádiz strengthened that liberal mentality for years.The strange departure of the Spanish Army The attempts at revolution that took place in Caracas and Buenos Aires in 1810 convinced him – or so say his biographers who are more permeable to the myth – that he should go to his homeland as soon as possible to take sides with his own. To tell the truth, there was nothing American about the Spanish officer, except for his place of birth. His were the members of the Spanish Army. He had spent his life outside the continent, his physical appearance was European and his accent was markedly Andalusian. José de San Martín asked to be discharged from the Spanish armed institutions to attend to “family matters in Lima”, which was a lie, and he was definitively convinced. of which side he wanted to be on when the imminent collapse of the Spanish Empire caught them all under. His was rather a liberal reverie above an independentist one. The Creoles organized themselves. On September 12, 1812, he married María de los Remedios Escalada, the teenage daughter of a powerful family of American aristocracy, in Buenos Aires. Her family was rich, prestigious and in favor of the rebellion, which meant an economic jump for José de San Martín, whose only fortune was the one he had managed to accumulate during his career at the service of the Spanish Empire. In fact, his wife's family called him "the soldier" and sometimes "the Andalusian", because he played the guitar and spoke in the manner of that land. In 1813, the Andalusian joined the rebel army at the head of a body of elite fighter, the Horse Grenadiers, who became known in their victory at San Lorenzo, preventing the landing of a royalist army. Without a doubt, the talent and military experience of someone like San Martín were going to be crucial in bringing down the last bastion of the Spanish Empire in South America:the land sown by Pizarro.

The Battle of San Lorenzo, by Julio Fernánez Villanueva- Instituto Nacional Sanmartiniano Although in the viceroyalties of New Granada and Río de la Plata the independence processes were instantly successful, the same did not happen with the Viceroyalty of Peru, once the key piece of Hispanic power. The greater presence of peninsulars than in other territories, the scant implantation of the independence spirit and the leadership capacity of Viceroy José de Abascal turned the place into a rock in the way of the rebels. With an army of about 42,000 men, Abascal crushed any attempt at rebellion in Peru, Quito, Upper Peru and the captaincy general of Chile. To defeat him, the joint action of Bolívar and San Martín would be necessary, as well as the military ingenuity of the Bailén veteran. The "Andalusian" soldier applied his military knowledge in mountainous areas to orchestrate a surprise attack on Chile, and from there by sea to Bajo Peru. This campaign gave rise to the battle of Chacabuco on October 12, 1818, which cleared the way to reach Santiago de Chile three days later. That masterful action, which forced him to cross the Andes with his army, caused his comrades-in-arms and even his rivals to ignite comparisons between San Martín and Napoleon and Hannibal. Because to tell the truth, San Martín was a fair rival and never showed bloodthirsty with the Spaniards as Bolívar seems to have done. His enemies recognized him that way.

The Battle of San Lorenzo, by Julio Fernánez Villanueva- Instituto Nacional Sanmartiniano Although in the viceroyalties of New Granada and Río de la Plata the independence processes were instantly successful, the same did not happen with the Viceroyalty of Peru, once the key piece of Hispanic power. The greater presence of peninsulars than in other territories, the scant implantation of the independence spirit and the leadership capacity of Viceroy José de Abascal turned the place into a rock in the way of the rebels. With an army of about 42,000 men, Abascal crushed any attempt at rebellion in Peru, Quito, Upper Peru and the captaincy general of Chile. To defeat him, the joint action of Bolívar and San Martín would be necessary, as well as the military ingenuity of the Bailén veteran. The "Andalusian" soldier applied his military knowledge in mountainous areas to orchestrate a surprise attack on Chile, and from there by sea to Bajo Peru. This campaign gave rise to the battle of Chacabuco on October 12, 1818, which cleared the way to reach Santiago de Chile three days later. That masterful action, which forced him to cross the Andes with his army, caused his comrades-in-arms and even his rivals to ignite comparisons between San Martín and Napoleon and Hannibal. Because to tell the truth, San Martín was a fair rival and never showed bloodthirsty with the Spaniards as Bolívar seems to have done. His enemies recognized him that way.Bolívar or nothing! San Martín's string of victories led the liberal government established during the Liberal Triennium in Spain to negotiate a peace with the Latin American rebels. However, when the talks broke down, the liberator resumed the armed struggle and occupied Lima on July 6, 1821 with the title of Protector. He expelled thousands of Spaniards notoriously anti-independence and confiscated their property. On a political level he established freedom of trade and freedom of the press, but did not allow religious worship other than Catholic. The Liberator hoped during his protectorate to be able to complete the independence of the national territory and prepare the way for the establishment of a constitutional monarchical regime, which has led some to maintain that the government of San Martín was a dictatorship. The type of State that should being established in Peru generated a gap between the supporters of a monarchy and those of a republic. For monarchists like San Martín, the republic was not the most convenient form of government for Peru due to the large extension of its territory and the poor education of the country's masses. He knew better than anyone how savage a people could be in the event of anarchy, and that is why he wanted a kingdom for Peru preferably led by a European Prince, the Infante of Castile if possible. An old idea that the Bourbons themselves had weighed in the past:a kind of Hispanic kingdoms led by the members of the dynasty. Not in vain, the form of government of Peru and the rest of the new states that were emerging was one of the topics discussed by San Martín and Simón Bolívar, the great leader of the Corriente Libertadora del Norte, during their meeting in Guayaquil on July 26, 1822. In this meeting, Bolívar was not very convinced that San Martín was in favor of a democratic republic. José Acedo Castilla considers in his study “The political performance of the general” that San Martín believed that “bringing the most uneducated to the Government and giving them prominence was a political disaster.” Bolívar himself maintained that the liberator of Peru “did not believe in democracy, being convinced that those countries could only be ruled by vigorous governments, which enforced compliance with the Law, since when men do not obey it voluntarily, there is no choice but force. In short, San Martín was a product of the liberal ideas of his time:a liberal constitutionalist, who conceived the Government in strong and clean hands and "not given over to the ignorance, envy, resentment and desire for profit of certain people ». Education had to come before democracy. When San Martín offered him the leadership of the liberating campaign in Peru, Bolívar made him understand that he would only accept it if he withdrew from Peru. Either Bolívar or nothing!

A voluntary exile and nostalgia for Spain Upon his return to Lima, San Martín was clear that he had to leave the way to Bolívar free. His time as a liberator, now that his military side was no longer needed, was coming to an end. This plan accelerated when he learned on his return that the people of Lima had captured and expelled Bernardo Monteagudo, his right-hand man in government and another defender of the monarchy. With great difficulty, the Argentine managed to reunite the First Constituent Congress, which from the beginning was controlled by the liberal republicans. The same day of his installation (September 20, 1822) San Martín presented his irrevocable resignation to all the public positions he held. With the Spanish still controlling some provinces, Peru needed Bolívar's troops if it wanted to carry the independence process to port. . His parting words had that tragic air so characteristic of betrayed heroes:«The presence of a lucky military man, no matter how selfless he may have, is fearsome to the newly constituted States. On the other hand, I'm already tired of hearing that I want to become sovereign. However, I will always be ready to make the ultimate sacrifice for the freedom of the country, but in a simple private class and no more.”

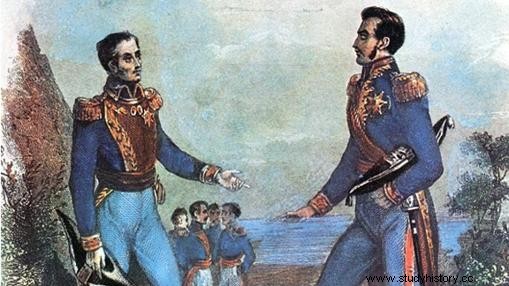

Guayaquil interview between José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar. From Peru he asked permission to meet again in Buenos Aires with his wife, who was seriously ill. But since it took so long to arrive, between delays sponsored by his enemies, his wife had already died on August 3, 1823. At the beginning of the following year he left for the port of Le Havre (France). He was 45 years old and behind him he left his positions as generalissimo of Peru, captain general of the Republic of Chile and general of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. He briefly visited England, Italy and other European countries until he settled definitively in France, where he would live until his death in 1850. In his long European exile, San Martín nostalgically recalled his time in Spain and avoided economic hardship only with the assistance of a wealthy friend of his, the Spaniard Alejandro Aguado. return to America, and even embarked for this purpose, but ultimately preferred to remain on the sidelines of the internal struggles that followed the Spanish power on the continent. Buenos Aires was consumed during a civil war in which he was warned not to get involved. It was not until 1880 when his remains could be repatriated and transferred to the Republic of Argentina. Now yes, the myth was mature enough.

Guayaquil interview between José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar. From Peru he asked permission to meet again in Buenos Aires with his wife, who was seriously ill. But since it took so long to arrive, between delays sponsored by his enemies, his wife had already died on August 3, 1823. At the beginning of the following year he left for the port of Le Havre (France). He was 45 years old and behind him he left his positions as generalissimo of Peru, captain general of the Republic of Chile and general of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. He briefly visited England, Italy and other European countries until he settled definitively in France, where he would live until his death in 1850. In his long European exile, San Martín nostalgically recalled his time in Spain and avoided economic hardship only with the assistance of a wealthy friend of his, the Spaniard Alejandro Aguado. return to America, and even embarked for this purpose, but ultimately preferred to remain on the sidelines of the internal struggles that followed the Spanish power on the continent. Buenos Aires was consumed during a civil war in which he was warned not to get involved. It was not until 1880 when his remains could be repatriated and transferred to the Republic of Argentina. Now yes, the myth was mature enough.SOURCE:http://www.abc.es/historia/