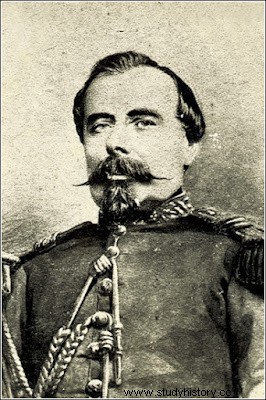

Bolognesi was born on November 4, 1816, in Lima. He was the son of the Italian musician Don Andrés Bolognesi and Doña Juana Cervantes from Arequipa. He was baptized in the church of San Sebastián, where Santa Rosa and San Martín de Porres had also been baptized. He was almost the "son of independence" and his family had vibrated with the most beautiful passages of it and had also suffered with the attacks of the royalists and the first frustrations of the Republic. It is not, therefore, difficult to understand the patriotic environment in which Francisco Bolognesi grew up; neither was the impact such sentiment had on his tender heart. He had been born, then, in the midst of the struggle for American freedom, whose proclamation would lead him as a guide in his civil and military life.

Francisco Bolognesi HE WORKED FROM A VERY YOUNG AGE For eight years he worked as an accountant for a company in Arequipa and made long trips to Puno and Cusco. In the year 1832, when he was barely 16 years old, he was hired to work in the accounting section of an important commercial firm, whose owners saw in him great capacity and remarkable honesty.

Francisco Bolognesi HE WORKED FROM A VERY YOUNG AGE For eight years he worked as an accountant for a company in Arequipa and made long trips to Puno and Cusco. In the year 1832, when he was barely 16 years old, he was hired to work in the accounting section of an important commercial firm, whose owners saw in him great capacity and remarkable honesty.HE DEDICATED TO BUSINESS COMMERCIAL That position was exercised together with another commercial activity of great importance for the family sustenance, that of making trips to the east, to the jungles of Puno (Carabaya) and Cusco (valley of La Convencion), in order to buy coca and husk for move them to Arequipa and sell them. Those were times when traveling along that route was difficult and, for this reason, only young people who had a spirit of adventure and a desire for wealth made it. They moved along rough bridle paths, on trips that lasted several weeks. Those caravans had no fear of passing through the inhospitable yungas, the cold punas, or the hottest omaguas. Along the way they were encouraged by the locals who provided them with food and lodging at ridiculous prices, in addition to the necessary advice and contacts.

WHAT WERE THE COCA AND THE HUSK USED FOR? The coca, which they obtained in the Selva Alta regions, was transferred to Arequipa and sold to commercial houses or to rich landowners, who gave this stimulant to their workers or laborers as part of the payment of their wages or as consideration for their services. For putting within their reach the "sacred leaf of the Incas", the merchant who took them from such distant places was rewarded with the guaranteed sale. Cascarilla is also a tropical shrub, very useful, because quinine is extracted from it, a medicinal substance that at that time was used to combat malaria, an endemic rooted in all the yungas or inter-Andean ravines of Peru.

“THE EXCEPTION THAT CONFIRMS THE RULE” Accounting and commerce were carried out by Francisco Bolognesi until 1840, when he was almost 24 years old. In those times, of caudillismos and revolutions, it was common to observe in the state and private armies, that of these many there were, very young people, a tradition that they had inherited from the times of the precursors and heroes. The military career was the most popular and interesting among the youth of that time. Francisco Bolognesi, who had broken this tradition, because he had first started as an accountant and merchant, was one of those exceptions that confirm the rule and recently assimilated into the Peruvian army in 1853, at the age of 37.

BOLOGNESI WAS A CASTILLISTA Between the years 1854 and 1855, in the partisan struggles between the caudillos for political power, Francisco Bolognesi leaned towards the distinguished figure of Don Ramón Castilla, when this caudillo faced Rufino Echenique, at that time the supreme president of Peru. The revolution of Castile began in Arequipa at the end of 1854 and the great marshal went to Lima. His and Echenique's troops clashed in the battle of Las Palmas, on January 5, 1855, Echenique being defeated and Castilla assumed the government as provisional president, beginning his second government period. It was one of the many coups that have taken place in Peru since its creation as a Republic. Bolognesi knew from those days what the ups and downs of power were like.

HE EXPERIENCED A GENEROUS MILITARY ACT In 1858, Bolognesi was promoted to the colonel class of the Peruvian army. In 1860, when Ramón Castilla's troops arrived by land and sea to Ecuador and Castilla entered Guayaquil, in order to teach a historical lesson to the Ecuadorian government that had pretensions of annexing the northern part of Peru to its country, Bolognesi was on that victorious expedition. He was, then, an actor in the days of glory with which the Peruvian army was covered, mainly because Castilla made things clear with the brother country of the north and said goodbye to his occasional rivals without any rancor, without having charged them the quota of victory. and, on the contrary, after having showered the Ecuadorian military with gifts, even leaving them with campaign uniforms. Bolognesi learned of the generosity of his commander and president of Peru.

WEAPONS THAT SERVED TO DEFEND THE COUNTRY After that conflict, Francisco Bolognesi was sent to Europe to acquire weapons for the Peruvian armed forces; with the special order to buy cannons for the navy and the fortification of Callao. This acquisition made by Bolognesi was extremely useful and served to successfully defend the integrity of Peru and America in 1866, when a Spanish army tried to reconquer Peru and attacked Callao, Combate del Dos de Mayo, coming out totally defeated. The most praiseworthy aspect of Bolognesi's acquisition of arms in Europe was the fact that our distinguished patriot paid with his own money the cost of 7 pieces of artillery and that, according to the notary and administrator of the Main Treasury of Lima, Mr. Juan Ignacio Elguera , amounted to the sum of 1,436.00 pounds sterling and that the Peruvian State had recognized and that it should pay him with an annual interest rate of 6%.

HE MODERNIZED THE ARTILLERY WEAPON AND INTERVENED IN THE WAR In 1868, due to his indisputable merits, Bolognesi was appointed General Commander of Artillery, a position from which he made every effort to modernize said weapon of the Peruvian army. In April 1879, when the War of the Pacific was declared, Bolognesi was appointed Chief of the Third Division of the South and marched with his troops to defend the Tacna-Arica front, an area that was considered by the Chileans as strategic terrain and where it was defined actually the ground campaign. The most decisive encounters took place, in effect, in that territorial strip, and Bolognesi played a prominent role in the battles of San Francisco and Tarapacá, the Chileans having been defeated in the latter.

A DEBT PUBLIC THAT THE STATE DID NOT HONOR

In the year 1870 the Peruvian State had not yet honored the debt it had with Bolognesi for the acquisition of the 7 Blackelly cannons and that our hero had bought with his silver in Europe for the defense of Callao in the year 1866. Bolognesi protested indignantly at this breach and writes a letter to the Minister of Finance. In one of its paragraphs it even says that "... he has found abandoned in the general Customs park 7 Blackelly cannons of his property, scratched..."

In 1873, Bolognesi decides to name Aquiles Fonayre as his representative, who, in another letter addressed to the authorities of the Executive Power and the Ministry of Finance, notes that due to the time elapsed and the interest accrued, the debt amounted to 10 thousand soles, a complaint that had already been submitted to the courts. In other words, the State had been sued.

Two years before the War of the Pacific, in 1877, Francisco Bolognesi wrote a moving letter, once again addressed to the Ministry of Finance, reminding it that he was still owed 10,020 soles , according to the liquidation calculations carried out by the General Directorate of Accounting and Credits of said portfolio.

On February 22, 1877, Mauricio Félix Torres, representative of the Ministry of Finance, recognized that the debt to Bolognesi amounted to reality at 13,674.03 soles. When the War of the Pacific broke out two years later, Bolognesi had another noble gesture:he postponed claiming him "for another occasion".

AN UNCOMFORTABLE MILITARY POSITION But, the Chilean superiority was manifest; something that became more noticeable when the Bolivians definitively withdrew from the war. Bolognesi suffered in his own flesh this dissimilar situation, which he knew how to cope with decorum and heroism. Indeed, Bolognesi, when the Peruvian army withdrew to Tacna, remained in Arica, leading a garrison of 2,000 soldiers. In the port of Arica was the original location of this small detachment. There, in Chinchorro, there was a mansion that served Bolognesi as his headquarters. A few meters away rose the Morro de Arica, a hill with gentle slopes facing the continent and a very high and steep cliff facing the sea.

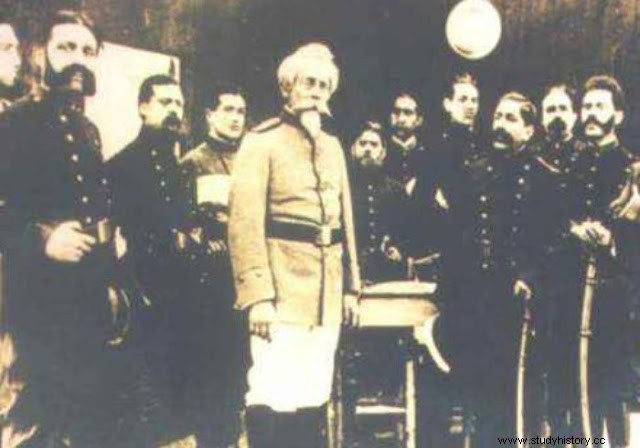

BOLOGNESI'S HISTORIC RESPONSE The Chileans had to pass through this port to reach Tacna, which is further north and with which it is linked by a railway, through which Bolognesi could very well have ordered the withdrawal of the soldiers from it. In the early morning of June 6, it is noted that more than eight thousand men of the Chilean army station themselves in front of Arica and point their cannons towards the general headquarters and the nose. Chilean General Baquedano sends Major Salvo to Bolognesi, asking for immediate surrender. The veteran colonel, with the words that only inspire moments of glory, replies by saying:"Major, tell your general that I am not giving up and that I will fight until the last cartridge is burned." But, when Major Salvo was already leaving, he calls him and tells him to wait, "... in front of him he is going to consult with his officers." It was, without a doubt, the wise advice of experience and noble sentiments. The old soldier had realized that it would be selfish of him to speak on behalf of everyone, especially all ... the young.

Bolognesi's response Bolognesi ordered his aide-de-camp to convene a War Council. All his officers hurried to attend, eager to know the Chilean's message. Bolognesi, with that solemnity that gives the joy of giving a sublime sacrifice for the country, transmits to his officers Salvo's proposal and also the answer he had given. When he was about to explain the reason for his decision, almost in unison and without waiting for the explanation to finish, one by one, his worthy officers adhered to Bolognesi's words, to the pathetic admiration and dismay of the Chilean military. the afternoon of June 6, 1880. Since those hours, preparations are redoubled to defend the hill, symbol of the homeland and freedom. Bolognesi gives orders without ceasing. The few batteries are placed in strategic places; the nose is mined to make it "fly if necessary"; soldiers, supplies and food are distributed. The vigil appears eternal, endless; in the morning it seems that there will be no light.

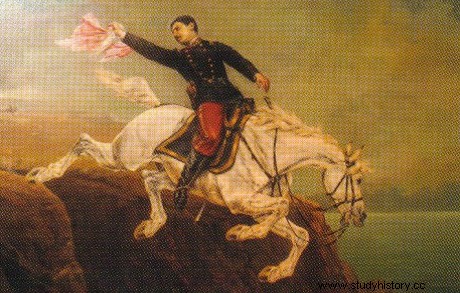

Bolognesi's response Bolognesi ordered his aide-de-camp to convene a War Council. All his officers hurried to attend, eager to know the Chilean's message. Bolognesi, with that solemnity that gives the joy of giving a sublime sacrifice for the country, transmits to his officers Salvo's proposal and also the answer he had given. When he was about to explain the reason for his decision, almost in unison and without waiting for the explanation to finish, one by one, his worthy officers adhered to Bolognesi's words, to the pathetic admiration and dismay of the Chilean military. the afternoon of June 6, 1880. Since those hours, preparations are redoubled to defend the hill, symbol of the homeland and freedom. Bolognesi gives orders without ceasing. The few batteries are placed in strategic places; the nose is mined to make it "fly if necessary"; soldiers, supplies and food are distributed. The vigil appears eternal, endless; in the morning it seems that there will be no light.THE BATTLE OF THE MORRO DE ARICA On June 7, 1880, from very early hours, the Chilean cannons begin to rumble. The Peruvians respond furiously but the others are too many. The Chilean infantry and cavalry regiments announce their departure with dense clouds of dust. Bolognesi, made a titan, harangues, stimulates, threatens. He is everywhere, it seems that he multiplied. But, the enemy troops do not enter minds and continue advancing. The Peruvians begin to fall back and the nose's explosion system does not work. Within a few minutes there is already a hand-to-hand fight. A Peruvian has to face ten Chileans and those are becoming less and less, while these seem to be more and more:many more. Bolognesi fights heroically. Saber in hand, he defends Peru, his honor and that of his comrades-in-arms. When there are very few Peruvians left standing, the Chileans surround the great soldier, riddle him with bullets, wound him with bayonets, and kill him at the Titan del Morro. Alfonso Ugarte sees the scene, takes the bicolor flag, spurs his horse and, before surrendering it to the enemy, jumps down the ravine into the depths of the hill. Arica has fallen into the hands of the Chileans, very soon the rest of Peru will, but the lesson of Bolognesi will elevate it to glory and immortality.

Sacrifice of Young Alfonso Ugarte BLOODY ASSAULT AND MORE THAN A THOUSAND DEAD “In that epic –says José Santillán Arruz- the Peruvian casualties were great:more than a thousand dead. The members of the Grenadiers of Tacna and Hunters of Piérola battalions, including chiefs, officers and troops, died almost in their entirety (Chile had 114 dead and 337 wounded). It was a heroic battle and one that could have been won were it not for the lack of reinforcements, including the men of Colonel Segundo Leiva, commander of the Second Army of Southern Peru. Hence Bolognesi's famous phrase in his telegrams to this officer when he writes “Hurry up, Leiva; it can still come!” The diary page belonging to a young soldier is preserved at the Institute of Pacific Historical Studies. In it, the conscript states that, having his weapon useless, he only waited for the death of his companion to pick up the rifle and continue fighting. "There are many soldiers in my situation," he confessed. The reason is that in Arica more than 70% of the rifles were Chassepot rifles, which had a needle-type hammer. After a couple of hours of use, the system wore out and the weapon became unusable.

Sacrifice of Young Alfonso Ugarte BLOODY ASSAULT AND MORE THAN A THOUSAND DEAD “In that epic –says José Santillán Arruz- the Peruvian casualties were great:more than a thousand dead. The members of the Grenadiers of Tacna and Hunters of Piérola battalions, including chiefs, officers and troops, died almost in their entirety (Chile had 114 dead and 337 wounded). It was a heroic battle and one that could have been won were it not for the lack of reinforcements, including the men of Colonel Segundo Leiva, commander of the Second Army of Southern Peru. Hence Bolognesi's famous phrase in his telegrams to this officer when he writes “Hurry up, Leiva; it can still come!” The diary page belonging to a young soldier is preserved at the Institute of Pacific Historical Studies. In it, the conscript states that, having his weapon useless, he only waited for the death of his companion to pick up the rifle and continue fighting. "There are many soldiers in my situation," he confessed. The reason is that in Arica more than 70% of the rifles were Chassepot rifles, which had a needle-type hammer. After a couple of hours of use, the system wore out and the weapon became unusable.DID THE PERUVIAN STATE PAY THE DEBT OF 1866?

In 1884, 4 years after Bolognesi's heroic death in the legendary Morro de Arica, his daughter, Mrs. Margarita Bolgnesi de Cáceres, in a letter addressed to the public powers, recalled that the State had an outstanding debt with his father. The Ministry of Finance made the corresponding liquidation and recognized that the heiress of the hero of Arica should be paid the sum of 20,239.07 soles. The State began to pay in drops and only finished doing so in 1905.

Lima, June 2009 Julio R. Villanueva Sotomayor