Philip IV, known as "the Beautiful", king of France from 1285 to 1314, owes his nickname to his immense stature and the beauty of his impassive face. “It is neither a man nor a beast, it is a statue .” said of him the French prelate Bernard Saisset. His reign is considered by historians to be one of the most important but also one of the most disconcerting. He is one of the main architects of French unity, along with Philippe Auguste and Louis XI. An enigmatic personality, perhaps a simple instrument in the hands of his legal advisers, the lawyers, Philippe le Bel is the sovereign of a strong and centralized state. He will be intransigent with the Templars whose wealth he covets and will obtain their condemnation and the suppression of their order.

Philip IV, known as "the Beautiful", king of France from 1285 to 1314, owes his nickname to his immense stature and the beauty of his impassive face. “It is neither a man nor a beast, it is a statue .” said of him the French prelate Bernard Saisset. His reign is considered by historians to be one of the most important but also one of the most disconcerting. He is one of the main architects of French unity, along with Philippe Auguste and Louis XI. An enigmatic personality, perhaps a simple instrument in the hands of his legal advisers, the lawyers, Philippe le Bel is the sovereign of a strong and centralized state. He will be intransigent with the Templars whose wealth he covets and will obtain their condemnation and the suppression of their order.

The promising beginnings of the reign of Philip the Fair

Son of Philip III the Bold and Isabella of Aragon, Philip IV ascended the throne at the age of seventeen. Having received Champagne and Navarre through his marriage to Jeanne de Navarre (1284), he was the first to bear the title of "king of France and Navarre". The acquisition of Navarre is temporary, but that of Champagne definitive. The young king immediately put an end to the sterile wars against Aragon (treaties of Tarascon and Anagni, 1291 and 1295). With regard to England, prefiguring the Hundred Years' War, he had Guyenne invaded (1294-1299) then returned it to Edouard by the Peace of Montreuil (1299), cemented by a double marriage:that of his sister, Marguerite, with Edward I and that of Isabella, her daughter, with Edward's son.

No one could imagine then that, Philip the Fair being the father of three sons, this double alliance would give kings of England of the rights to the crown and to provoke a hundred years of war. Peace was restored in 1303 (Treaty of Paris).

No one could imagine then that, Philip the Fair being the father of three sons, this double alliance would give kings of England of the rights to the crown and to provoke a hundred years of war. Peace was restored in 1303 (Treaty of Paris).

Philip IV attempted to annex Flanders by imprisoning Count Gui de Dampierre (1295) and confiscating his fief, placing a French governor at its head. The latter's tyranny provoked a terrible uprising of the Flemings in Bruges:the Bruges Matins (May 17-18, 1302). The French army was cut to pieces by the Flemish municipalities at the Battle of Kortrijk, also called "Golden Spurs" (July 11, 1302). The king does not participate directly in the battle, which probably saves his life.

On the other hand, he fought at Mons-en-Pévèle (August 18, 1304) and, victorious, was thus able to acquire, by the peace of Athis-Mons (June 1305), Lille, Douai and Bethune. On the side of the Empire, the king received from Otto of Burgundy the County of Burgundy, now Franche-Comté (March 1295). The Comtoise nobility is indignant. The most important acquisition of Philippe le Bel is the definitive attachment of Lyon (subordinate to the Holy Roman Empire, then to the Church) to France in 1312. It testifies to the extension of the territory towards the east.

The conflict with the Pope and the Anagni attack

Pious but anticlerical, Philip the Fair opposed papal interference in French affairs. He comes into conflict with Pope Boniface VIII, who opposes the levying, without his agreement, of decimes on the clergy, and the arrest and condemnation of Bernard Saisset, bishop of Pamiers. The bulls sent by the pope, recalling the pontifical theocracy (essential concept in the Middle Ages), aggravated the tensions, and Philippe le Bel decided to convene the first states general (1302-1303), which strongly supported the royal policy.

Supported by public opinion, he questions the validity of the pope's election and calls for his deposition. Boniface VIII then launched a ban on the kingdom of France and released the French from their oath of loyalty to the sovereign. The quarrel had reached a point of no return. Philippe le Bel therefore resolved to go even further and, on the advice of the most influential of his lawyers, Guillaume de Nogaret, to have the pope arrested in Italy itself. Nogaret took charge of the operation.

Leaving France secretly, he conferred in Tuscany with Boniface's Italian enemies, notably with the head of the very powerful Colonna family, Sciarra Colonna. At the head of an armed band, he went to the small town of Anagni, where the pope was spending the summer. On September 7, his people entered the city to cries of "death to the pope, long live the king of France". Boniface, neglected by all, having put on his pontifical robes, a crucifix in his hand, was awaiting death when he was arrested by Nogaret.

Leaving France secretly, he conferred in Tuscany with Boniface's Italian enemies, notably with the head of the very powerful Colonna family, Sciarra Colonna. At the head of an armed band, he went to the small town of Anagni, where the pope was spending the summer. On September 7, his people entered the city to cries of "death to the pope, long live the king of France". Boniface, neglected by all, having put on his pontifical robes, a crucifix in his hand, was awaiting death when he was arrested by Nogaret.

Contrary to legend, he was not beaten, but threatened and insulted. Nogaret reminded the pontiff of the accusations against him and wanted to take him prisoner. Protests then arose. The insults with which this old man had been showered and the courage he had shown aroused in his favor the inhabitants of Anagni. On September 9, Nogaret and his family had to flee the city. Boniface was taken back to Rome. But, very affected by this humiliation, exhausted and having partially lost his mind, he died on October 11.

The king then elected a French pope, Clement V, who came to settle in Avignon in 1309. This solution, which put an end to the conflict and which was to remain provisional, extends for three quarters of a century.

Philip the Fair's reforms

Under the influence of jurists, in particular Pierre Flote, Guillaume de Nogaret and Enguerrand de Marigny, monarchical centralization was accentuated by the specialization of the Royal Court into judicial sections ( Chambers of Investigations and Chamber of Requests) and in financial sections (Chamber of Money and especially Chamber of Accounts, created in fact after his death, in 1320). He fixes the Parliament in Paris, establishes the Grand Council to assist him in political decisions. A great innovation, it resorted to popular consultation by assemblies of barons, prelates, consuls, aldermen and mayors of communes, which foreshadowed the Estates General. He summons them on several occasions to ensure support for his policy.

The most difficult problem to face is, however, that of finances, as the king can no longer govern with the sole revenues of the royal domain. Philippe le Bel endeavors to settle it by attempting to impose regular taxes, by heavily taxing the Jews (expelled in 1306) and the Lombards, and by carrying out monetary changes, which earned him the reputation of a counterfeiter. . It sets up the maltôte (bad size), a tax on goods, and the gabelle, tax on the sale of foodstuffs, and particularly salt.

The Templar Affair

The most spectacular financial operation, if not the most successful, reached the Templars. For more than a century, the treasury of the Order of the Temple in Paris had become the true financial center of the monarchy. The wealth of the Templars excited the covetousness of the king and his entourage, even as the state coffers were constantly empty. Furthermore, the Templars had become unpopular. They were reproached for having retained their temporal and financial power in the West when they had failed to defend the Holy Land, to the protection of which their institution dedicated them. Moreover, the very mysterious mode of operation of the Order gave free rein to many legends, fueled by slander and popular vindictiveness.

Philip le Bel, advised or even manipulated by Guillaume de Nogaret, took advantage of this unpopularity, knowing that he would public opinion for him. The trial of the Order of the Temple and the confiscation of its wealth were decided and prepared by the King's Council in the greatest secrecy. On October 13, 1307, all the Templars residing in the kingdom were arrested and charged, starting with the Grand Master Jacques de Molay. Then began a very long trial which led to a council assembled in Vienna in 1311 and resulted in the suppression of the Order by a papal bull on April 3, 1312.

Philip le Bel, advised or even manipulated by Guillaume de Nogaret, took advantage of this unpopularity, knowing that he would public opinion for him. The trial of the Order of the Temple and the confiscation of its wealth were decided and prepared by the King's Council in the greatest secrecy. On October 13, 1307, all the Templars residing in the kingdom were arrested and charged, starting with the Grand Master Jacques de Molay. Then began a very long trial which led to a council assembled in Vienna in 1311 and resulted in the suppression of the Order by a papal bull on April 3, 1312.

During these five years, Pope Clement V had been hesitant and full of scruples. He was by no means convinced of the guilt of the order of the Temple. But he did not have the strength to resist the King of France, who showed himself intransigent and even threatening. He ends up capitulating and abandoning the order to its sinister fate.

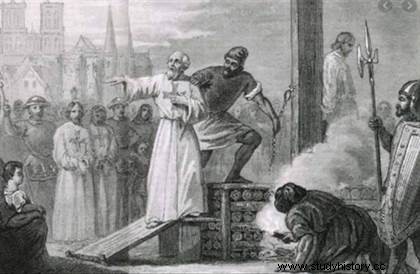

The Templars defended themselves very badly. Neither in England, nor in Germany, nor in Spain, had the investigations revealed any capital crime against them. But in France, subjected by the Inquisition to the most atrocious tortures, they gave up trying to defend themselves and confessed all that was wanted. The main dignitaries were also very clumsy and, by their Intransigence, led to the loss of most of their brothers. The Grand Master Jacques de Molay and the Commander of Normandy Geoffroy de Charnay, first sentenced to life imprisonment, denied their confessions extracted by torture. This retraction earned them to be delivered to the executioner and burned alive on a scaffold erected in the Ile de la Cité on March 18, 1314.

According to the judgment of the council, the sumptuous fortune of the Templars was entrusted to the custody of the order of the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem. But the crown of France knew how to take its part in passing, a considerable part. All the debts of the royal treasury to the Temple, and they were immense, were cancelled. In addition, the king's commissioners seized all the cash accumulated in the various houses of the Temple in France.

According to the judgment of the council, the sumptuous fortune of the Templars was entrusted to the custody of the order of the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem. But the crown of France knew how to take its part in passing, a considerable part. All the debts of the royal treasury to the Temple, and they were immense, were cancelled. In addition, the king's commissioners seized all the cash accumulated in the various houses of the Temple in France.

Finally, claiming, without proof and against all likelihood, that the Templars remained indebted to him for considerable sums, Philip the Fair forced the Hospitallers to pay him the sum of two hundred thousand books. Overall, the operation had been very successful for the king and the monarchy. Philip could hardly benefit from it, since he died a few months later following a hunting accident on November 29, 1314.

The legacy of Philip the Fair

Philip le Bel was the last great Capetian king whose policy ensured the kingdom a prestige and power that made France the first of the European nations. His three sons (Louis X le Hutin, Philippe V le Long and Charles IV le Bel) who briefly succeeded each other on the throne until the arrival of the Valois in 1328, tried to follow in his footsteps and take advantage of the immense work accomplished:feudalism gradually reduced to obedience, the Church become docile and submissive to the monarchy, the kingdom as a whole gradually organizing and expanding, acquiring administrative structures already prefiguring what a modern state should be .

The economic crisis, general in Europe, and the decline of the fairs of Champagne leave, with the death of the king, a dissatisfied country. The death without direct heir of the last son of Philippe le Bel opens an unprecedented crisis of dynastic succession among the Capetians which will lead to the Hundred Years War.

Bibliography

- Philippe le Bel, by Jean Favier. Text, 2013.

- Philippe le Bel, by Georges Minois. Perrin, 2014.

- France under Philippe Le Bel, by Edgard Boutaric. Nabu press, 2012.