The new gunpowder had characteristics that made it revolutionary compared to common gunpowder. It seemed obvious that it would be a clear competitive advantage for the army that used it first.

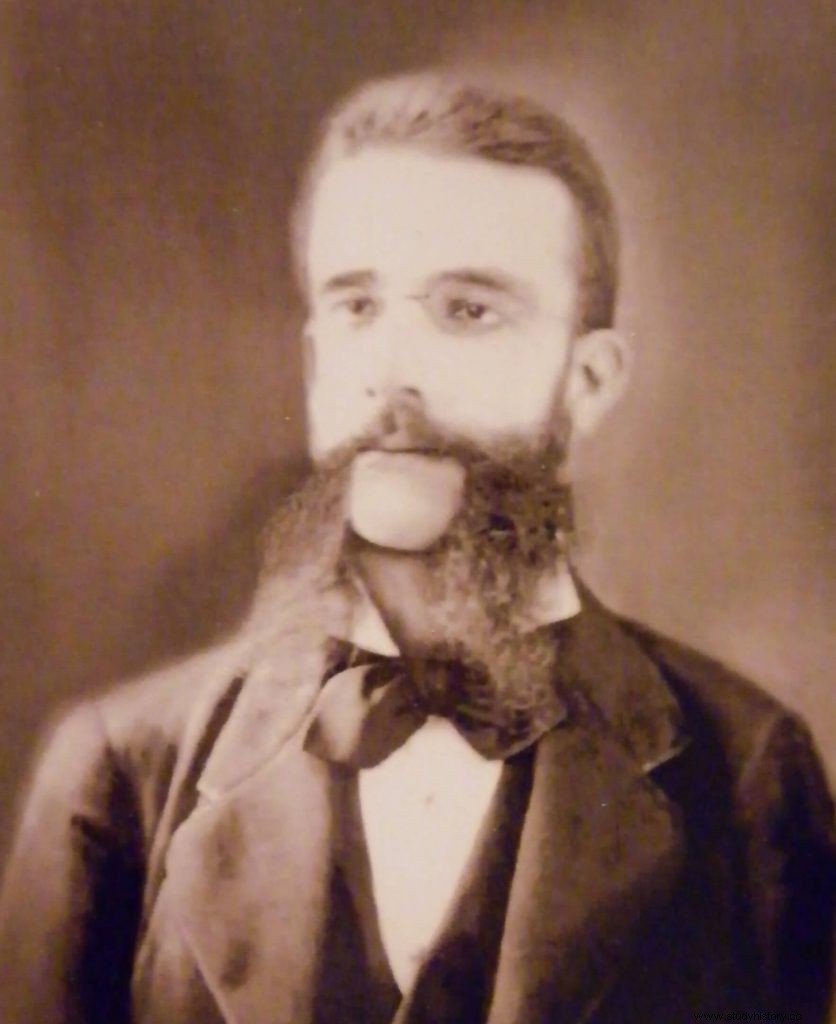

José Roura He was born in Sant Feliu de Guíxols in 1797. He received his doctorate in science from the Faculty of Sciences of Montpellier. He was a professor of chemistry at the Board of Trade School of Chemistry (1) and later the first director of the Barcelona School of Industrial Engineering. He was the man who illuminated Barcelona and Madrid for the first time with gas lighting, his most remembered professional milestone (3) . But in addition, he also stood out for building a steam engine in 1829, for participating in exhibitions with samples of an innovative transparent soap, for importing a system for dyeing and printing fabrics that represented a great advance for the Catalan dyeing industry, for building physics instruments such as barometers and thermometers. He published numerous studies on physics and chemistry, with special interest in those devoted to the wine industry and the distillation of spirits. Roura was an example of a life dedicated to science and technology in an effort to promote national industry and help raise Spain to the level of knowledge of other European countries. But of all his work, surely the most unknown and untapped despite his enormous potential was the invention of white or smokeless gunpowder.

What was the composition of the Roura gunpowder ? It is not known. Roura always kept his formula a secret. Despite the fact that France had offered him a million francs and that England was also interested in acquiring it, he only wanted to offer it to the Spanish army, preferring that his invention be unsuccessful before foreign powers could take advantage of it. It has been speculated that it was a gunpowder that belonged to the chlorinated class, and that Roura was ahead of other European scientists who were looking for similar products, such as the French chemist Claude Louis Bertollet. This possibility must be ruled out, since chlorinated gunpowder is an unstable variant of black gunpowder and in no way coincides with the characteristics of Roura gunpowder.

It has also been written that Roura gunpowder was like the gunpowder invented in 1849 by Augendre (American white gunpowder), a white gunpowder made with cane sugar as one of its ingredients. Although this type of powder had some advantages over black powder, it had the serious drawback of rusting the iron barrels very quickly and being excessively dangerous when detonated by shock, so it would also be necessary to rule out that Roura's composition was of this type. .

Officially smokeless gunpowder or white powder was manufactured for the first time in 1884 by the French chemist Paul Vieille by dissolving nitrocellulose in a mixture of alcohol and ether. Nitrocellulose was invented by Schönbein in 1846 (2) , was the so-called "cotton-gunpowder" or pyroxylin, a cotton-based explosive. Its industrial manufacture for military purposes failed due to the danger of explosions in factories. Very probably, according to the characteristics published as a result of the tests that were carried out, the Roura gunpowder must have been derived from nitrocellulose. Perhaps it was similar to the one invented in 1864 (nearly twenty years after Roura's invention) by the Prussian Army artillery captain Schultze, which was the first smokeless powder manufactured to replace black powder. It was known as "wood gunpowder" for having replaced cotton with wood cellulose. It was manufactured on a large scale in the German city of Potsdam and was used mainly in mines and for hunting. Some drawbacks, such as burning too quickly, discouraged its use for military purposes.

What were the characteristics of Roura gunpowder What made it better than the black powder used to date and what makes you think that Roura was able to advance up to two decades with his invention?

- Roura gunpowder was colorless in its natural state, which is why its inventor called it white gunpowder.

- It was less heavy, less hygrometric and more flammable than the common one and produced less recoil from the weapon.

- It left almost no residue on the weapon.

- It heated the weapon very little, allowing a greater number of shots to be fired in a row.

- It produced very little smoke and what it did produce was colorless and odorless and vanished instantly.

- Its preparation, packaging and transport were cheaper, as the amount needed to produce the same effects was less

- It was applicable to all the uses to which common gunpowder was intended, therefore, it could be adapted to rifles and artillery weapons.

- According to its inventor, its preparation was easy and less dangerous than the common one.

- It could be presented in grains like the common one with a force superior to the best English gunpowder.

- It lit with the same speed in dry and rainy weather, not damaging the humidity.

Trials of the Roura Gunpowder Army

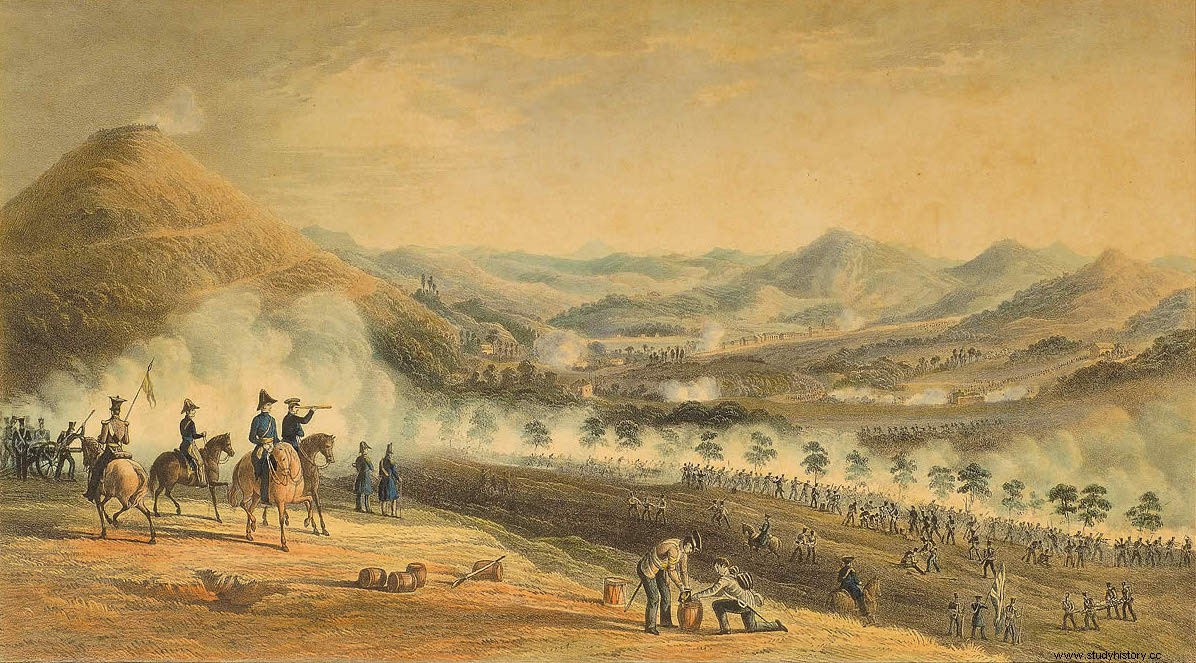

In 1847 General Domingo Dulce was Captain General of Catalonia. He had been appointed with the mission of quelling the war of the matiners who lived in the region. Dulce went several times to Roura's workshop to witness his work with the new gunpowder, and interested in any initiative that could improve the army, he encouraged her to present his product to the Government.

By Royal Order of the Ministry of War of September 6, 1847, Roura was requested to transfer to Madrid with expenses paid, including the damages that the displacement could cause him, with so that the “Military Inquiry Commission” could examine their discovery and know the advantages they could bring to military service. Roura argued that it was impossible for him to leave Barcelona with the necessary urgency. For this reason, a Royal Order of October 13 was issued authorizing the director general of the artillery to appoint a commission of officers from the Barcelona garrison to examine and carry out the appropriate tests on the invention.

On January 4, 1848, at the Atarazanas barracks in Barcelona he carried out the first trial . Several pistol, flintlock, and piston shots were fired on reams of paper with equal charges of black and white powder. According to the published results, the bullet fired by the white powder went through more than three times as many paper notebooks as the one fired by the black powder, leaving the bullet reduced to small sheets.

On January 10, early in the morning, Roura left his factory outside the walls in La Bordeta heading for the field of the Artillery Practical School, known as La Bota field. He had a cart pulled by a donkey, was loaded with all the necessary artifacts and accompanied by several professors, colleagues from the Faculty and a small number of friends. The captain general and his staff, all on horseback, occupied the firing range, providing Roura with the number of artificers and gunsmiths necessary for the experiments. He shot himself with a mortar and an eight-point cannon. One third less white powder was used than black powder and the result was that the bullet that weighed 60 pounds went further in all the shots with the Roura powder than with the black powder, some of them exceeding the target that the commission had prudently placed. at a point quite far away. The attendees were surprised by the little smoke produced by the shots and the speed with which it dissipated. Apart from the difference of the different scopes, the bullet fired with the Roura powder was lost entirely from sight and produced less recoil from the weapons. White's superiority was confirmed.

Given the good results, General Dulce decided that Do a few more tests. On February 2, at the Atarazanas barracks, it was tested whether the force of the white powder could cause the barrels of the rifles to burst. It was fired and they resisted. Attempts were also made to reduce gunpowder to powder keg by friction. It could not be achieved, after a good time of agitation the shape of the grains remained intact.

On March 2, the hygrometric power of both gunpowders was tested in the same place. Two equal samples of both gunpowders were locked in a trunk with a saucer of water. After 5 days they were weighed and it was found that the Roura was much less hygrometric.

In June 1848, encouraged by the good results of the military trials, he presented his invention to the Board of Trade for which he was professor and to the newly created Industrial Institute of Catalonia. He also read a work entitled Report on the properties and uses to which white powder can be put before the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts of Barcelona.

Over the next two years, Roura continued to perfect his gunpowder and believing in the great potential that he had. On February 9, 1851, new tests were carried out in his chemical factory-laboratory in La Bordeta. The Diario de Barcelona, in its February 12 edition, echoed the results in:

Thanks to his friendship with the former Captain General of Catalonia, General Manuel Gutiérrez de la Concha, Roura got Queen Elizabeth II interested in the invention of him . The queen appointed the Duke of Riánsares to represent her in new tests that would be held first on March 20, 1851 at the Casa de Campo in Madrid and then, on April 14, at the Hippodrome. Tests were carried out with Spanish and English rifles and a percussion rifle for infantry use, a bronze cannon and other flintlock weapons, repeating the success of previous tests. The newspaper El Popular published about the event:

Thanks to the great success of the trials, Roura was appointed, on April 26, 1851, Knight of the Royal Order of Carlos III and Royal Commissioner at the Universal Exhibition in London in 1851 But the Government's response was long in coming. Roura, impatient, published in 1852 a "Synoptic table with the results and data on the official tests on white powder".

Finally, the Government did not decide to manufacture it. The reason is unknown . It was said that it could have greater susceptibility to fire and too much strength for small arms, although this was not proven in tests. The only thing certain is that, unfortunately, the discovery was soon completely forgotten.

Since Roura's death in 1860, his descendants had preserved a sample of the gunpowder in a glass tube, wrapped and tied with the paper on which the composition was written. In 1988 the tube was lost during some works in the house. Almost in all likelihood, the last opportunity for history to recognize a Spanish scientist and inventor who, like so many others, remains forgotten despite his important work and discoveries, was also lost.

Notes

- The so-called schools of the Junta de Comercio (Real Junta Particular de Comercio de Barcelona) were in charge of technical education in the absence of a university in Barcelona. It must be remembered that the University of Barcelona was suppressed by Felipe V in 1717, and the only university that existed in Catalonia was that of Cervera. It was because of the distance and the quality of the education that Roura, like many other young people from Girona, chose to study in Montpellier, where he would arrive in 3 or 4 days of travel.

- Cristian Friedrich Schöbein conducting an experiment in his house accidentally spilled a mixture of nitric acid and sulfuric acid on the table, wiped it with her wife's cotton apron and hung it on the stove to dry. The apron swelled up and disappeared. He had converted the cellulose in the apron into nitrocellulose.

- The chronicles of the time echoed the great success of lighting Puerta del Sol, Plaza de Oriente, Calle de Alcalá and other streets in the center of Madrid with 201 gas lamps to celebrate the birth of the second daughter of Fernando VII, the infanta María Luisa Fernanda, on the night of January 30, 1832.

Bibliography

- Maria Dolors Martínez i Nó. (1993). Josep Roura (1797-1860):precursor of Catalan industrial chemistry. Association of Industrial Engineers of Catalonia.

- Pere A. Fàbregas. (1993). A Catalan scientist of the 19th century:Josep Roura i Estrada (1787-1860). Enclopèdia Catalana, S.A.

- Andrés Avelino Pi and Arimon. (1854). Ancient and modern Barcelona, description and history of this city from its foundation to the present day. Printing and polytechnic bookstore of Tomás Gorchs.

- Pedro Roqué and Pagani. (1851). Industrial chemistry course. Printing of the future by B. Bassas.

- Antonio Elias de Molins. (1889). Biographical and bibliographical dictionary of Catalan writers and artists of the 19th century. Fidel Giró print

- Charles E. Munroe. (1888). Lectures on chemistry and explosives. Torpedo Station Print.

- Arturo Masriera. (October 31, 1922). Of the eighteenth-century Barcelona. The Vanguard.

- Francisco Feliú de la Peña. (1850). Fundamentals of a new military code. Juan Olivares Printer.

- Jose Oriol Ronquillo. (1857). Dictionary of mercantile, industrial and agricultural matters, which contains the indication, description and uses of all merchandise . print Agustín Gaspar.

- Newspaper of Barcelona (April 12, 1851). Roura gunpowder.

- Almanac for everyone, religious, historical, scientific, literary, commercial and advertising for all of Spain. (1860). Juan Oliveres editor.

- The Gazette. (April 9, 1851).