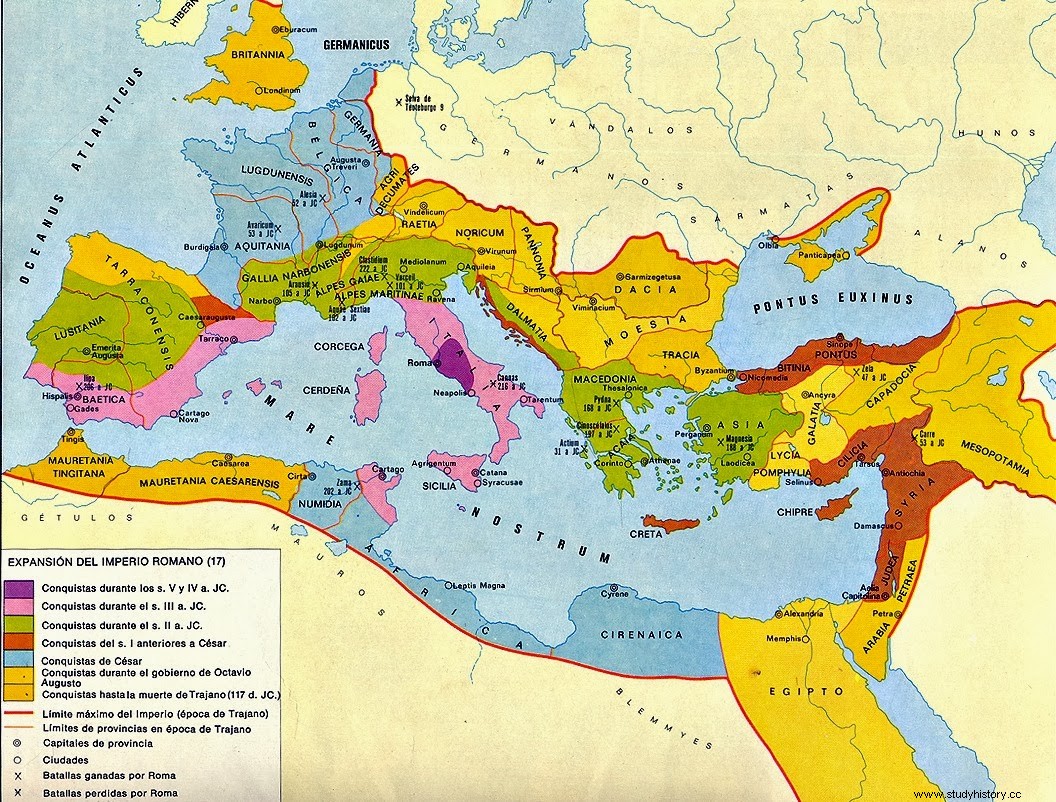

The Romans left a political and cultural legacy that influenced the world for centuries and that still remains in time today. The history of Rome lasted for more than a thousand years and, for better or worse, is rooted in our political, cultural and literary traditions, and even in our way of thinking. Logically, this romanization or process of assimilation of the culture and way of life of the Romans began with the conquest. A ruthless conquest, but let's not throw our hands in our heads, simply typical of its time, of a violent world and militaristic societies. That small city on the banks of the Tiber, normal and without great strategic advantages, took over most of the known world thanks to its engineers and its legions. And not only because the legions were well organized, trained and armed, but also because of the number of soldiers they could deploy on the battlefront. That I ask Hannibal, that he did nothing but defeat legions and legions and Rome kept sending more and more. And this is achieved by turning your enemies into allies or slaves, depending on how receptive the conquered are; integrating them as auxiliary troops and even granting them Roman citizenship. Obviously, given the theme of this article, we are going to leave cultural, linguistic or literary heritage aside and focus on the bloodiest and most ruthless part, but without trying to demonize or judge it. Now that I speak of judging, do you know that Julius Caesar was considered to be judged for his crimes committed during the conquest of Gaul? And I say it was raised, because they must still be running with their hats to the one who had the brilliant idea. The explanation is very simple, he was a political rival of the military man and you know that in politics, yesterday, today and always, anything goes. Besides, he wanted to be judged by the conquered tribes... the things of the world of politics.

And to begin the criminal history of Rome, we will go through the etymologies, a resource that I use very often because it is very illuminating. The first etymology is that of the term foundling , from Latin expositus (expose, put out). In Rome, newborns had to face the verdict of the paterfamilias:sublatus (take it) or expositus (leave him). If he picked it up off the ground, it meant that he accepted it, legitimized it and began to enjoy all the rights and privileges as a member of the family. If, on the contrary, they were not accepted, the son was exposed, that is, he was abandoned. In such a case, the newborns either died or were adopted by other families. In many cases, they were picked up by slave traders who raised them to later sell them or, in the case of girls, by a pimp who ran a brothel to put them to work as soon as they could. The abandonment of children was a common practice in both rich and poor, without going any further, and according to mythology, the founders of Rome were two abandoned babies. Seneca justifies it like this:

We exterminate the rabid dogs and we kill the wild and wild ox, and we slaughter the infected cattle so they don't infect the entire herd; we destroy the monstrous Parthians; and even our children, if they were born deformed, we drowned them; and it is not anger, but reason, that separates healthy elements from the useless.

The criteria used to abandon newborns could be due to some disability or physical deformity, for doubting that they were theirs, for not being able to feed them, in the case of the poorest, and for testamentary issues, for the patricians.

In fact, in Spain the surname Expósito it was assigned to the children of unknown parents who had been abandoned in the inclusas, hospices or foundling houses. As these children did not have known parents, they were given the surname of Expósito, which betrayed their condition as abandoned children and became a social stigma. As of 1921, the law was modified so that the Expósito surname could be changed for any other and free of charge.

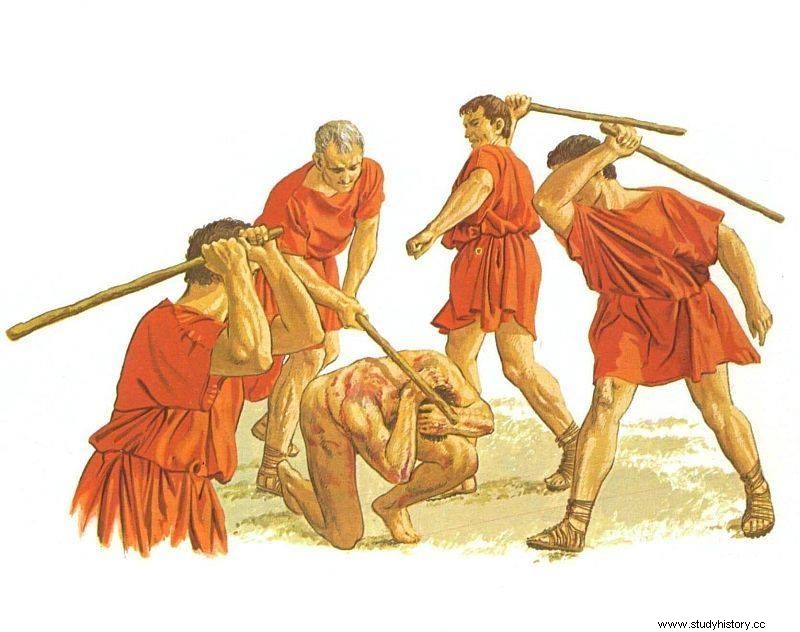

The second term that we are going to focus on is the verb tithe , cause a great mortality or punish one in ten, and that has its origin in the decimatio , a typical Roman punishment of the legions. Groups of 10 were made and one was chosen at random, and the other nine had to kill him by beating him with sticks. If anyone refused to do so, he suffered the same fate. It was an extreme punishment applied when legions mutinied or fled from the battlefield. As a lesson and warning to sailors, it was priceless.

And speaking of warnings, it was also necessary to toughen the sentences of those who sought tricks not to enlist. As with regard to being a Roman citizen, age and height could not do anything, to avoid recruitment some had their thumbs amputated so they could not hold the sword and, in this way, be exempt. In the time of Caesar Augustus, a wealthy citizen was found to have cut off the thumbs of his two sons and was sold into slavery. In 368, with Rome already very weakened and the barbarians knocking on doors, this occasional practice became common and the penalties had to be toughened, including being burned at the stake.

We will leave military life aside (by the way, from the Latin castrensis , military camp) and we will deal with the civilian population, where crimes were the order of the day.

Even with the revolutionary sewage system that turned the Tiber into a river sewer and laws that prohibited dumping garbage inside the city, Rome was a dirty city, very dirty. In its streets, the garbage generated in the houses and that people threw on public roads, excrement of all kinds of animals, corpses... and, at night, very dangerous. The poet Juvenal used to say…

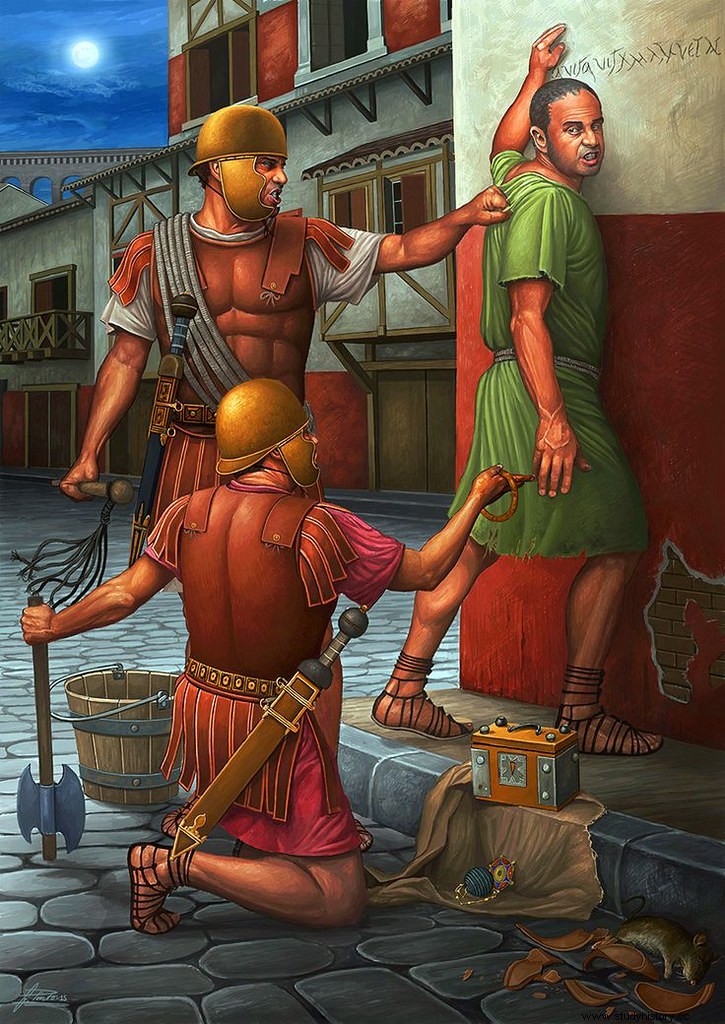

At night they throw broken pots and pans out onto the street, useless objects that crash to the ground if they don't find you along the way. There is death under every open window as you pass. I assure you:you will be reckless if you go to a dinner without first having made a will. You must consider yourself lucky if you spend a night on the streets and the only thing that is poured on you is the stinking contents of the chamber pots. […] But this is not the only thing that is terrible. Robbers abound who rob you when no one can come to your aid, because all the doors are closed and the shops barred with heavy bars. The robber attacks you dagger in hand and the criminals act freely.

Although there were night patrols (the vigiles) these were not very abundant and were more concerned with putting out the frequent fires than dealing with thefts, robberies and even murders, so wealthy citizens used to protect themselves with their own escort of slaves armed and equipped with torches on their nightly journeys through the city. Walking alone in Rome at night was ill-advised, as one risked being mugged in those dimly lit alleys, so people rarely ventured out, except for the homeless and, of course, criminals looking for their dams. If you were robbed, the best thing was to give them your wallet, the hourglass and everything you were carrying, because if you resisted your body could appear the next morning in a corner or floating in the waters of the Tiber. Accidents were also frequent and the muleteers did not usually stop to see how you were doing. As the cars could not circulate during the day, they were going like crazy from here to there to transport their merchandise before the sun came up.

Others who were confused by the night were the camels that distributed opium through the streets, which in many cases sold it adulterated and cut. With a certainly scarce national production, Rome had to import the precious sedative from Egypt, and there were many who denounced that the opium shipments arrived without any control. So it was common for them to try to sneak low-quality opium such as tebaico -the best of antiquity- and even adulterated batches in which it was mixed with gum arabic or lettuce juice. So, the best thing was to go to the authorized establishments - at the beginning of the 4th century, in Diocletian's time, almost 400 registered stores - because although it was more expensive, you were sure that you were getting the opium of the good.

And to have low funds as Jupiter commands, they could not miss the gangs in the purest style Gangs of New York . Publius Claudius Pulcher , Roman politician belonging to a rich patrician family, was quite a character of his time. A spoiled posh boy who believed that the whole mountain is oregano. After a mediocre military career in Asia, where he instigated a revolt and was involved in a mutiny, he returned to Rome and began to be known for wading in all the puddles. Realizing that of joining hunger with the desire to eat, he married Fulvia Bambalia, 20 years his junior. Everything was laughter and frivolity until Claudio Pulcro, one of his graces, got out of hand and fell into disfavor with his family.

And what did he do? Well, taking advantage of the rejection of his family, he renounced the rank of patrician, had himself adopted by a plebeian family and changed his name to Clodius , which sounded more plebeian. In this way, he could opt for the position of tribune of the plebs, to which he would not have been able to aspire being a patrician. When Julius Caesar left for Gaul, he got the position of tribune and, from day one, implemented populist measures to win over the people. As if this were not enough, he took control of the streets of Rome through the guild gangs, the collegia, which he supported and encouraged. In fact, some, like Cicero, his great enemy, had to flee Rome to save his life. That spiral of violence could not end well and Milón , another gangster from a rival faction, caused a brawl on the Appian Way where Clodius was killed. During the trial, the late Clodius's thugs, now loyal to his wife Fulvia, resorted to all kinds of intimidation against judges and supporters of the accused, to the point that Cicero was afraid to speak on his behalf. In fact, his case for Milo is one of the worst defenses in history. Milo was condemned and had to go into exile, and Fulvia swore revenge against Cicero... and got it. Her moment would come when Lepidus, Octavio and the impressionable Marco Antonio, her third husband, constituted the Second Triumvirate and drew up the list of outlaws and enemies of the country to be liquidated, Fulvia was in charge of including Cicero. He was put to death at his villa outside of Rome, and Antony ordered his head and right hand to be nailed to the Forum for public ridicule. Dion Casio tells that Fulvia approached with her two children of hers to where the head of hers was, Cicero hated her, she pulled a hairpin out of her hair and pierced the speaker's tongue in a clear gesture of cold revenge.

And before all this, an almost testimonial urban police, who could do little or nothing. In addition, the prisons in Rome were not a punishment or a sentence, but simply the place of custody until the inmate was tried and sentenced according to the penalties provided for in the Law of the XII Tables, the legal text that contained the norms to regulate the coexistence of the Roman people.

Mamertine Prison (Rome)

And what were those penalties? Well, there was everything in the vineyard of Jupiter. In Roman society, the concept of sex has nothing to do with the modesty and embarrassment that this issue produces in us today due to the education received. But neither should we think that the entire mountain was oregano... and César Augusto took care of it. To restore the moral foundations of marriage and prevent scandalous behavior such as adultery, he enacted a law that established different penalties for the crime of adultery:

- The two culprits were punished with exile and, in addition, part of their property was confiscated.

- The father could kill his adulterous daughter and his mistress if he caught them red-handed in his house or her son-in-law's house, but as long as he went at the time.

- Under these same circumstances, if it is the husband who surprises them, he could kill her wife's lover and was forced to divorce her. In case of not killing the lover, the husband could retain him and punish him. Usually he was sodomized with a horseradish, by a slave (preferably a Nubian, I don't think I need to explain why) or by himself if he so pleased.

In cases of parricide, depending on the time, the parricide was thrown into the amphitheater to be devoured by beasts, handed over to the victim's family, or the poena cullei was applied. (sack penalty). This is how this penalty is described by a jurist of the 3rd century…

According to the custom of our ancestors, the punishment instituted for parricide was as follows:the parricide was whipped with blood-colored rods, then he was put in a sack with a dog, a dunghill rooster, a viper and a monkey; and then they threw the sewn sack into the depths of the sea.

And the arsonists? With the arsonists it was especially cruel and they were paid with their own coin, with the so-called “bothering tunic ”. As good followers of "bread and circuses", the emperors tried to provide entertainment to the citizens of Rome, always trying to overcome what their predecessors had done, either because of the originality or because of the cruelty used, and for this they resorted to Mythology. One of these mythological recreations was that of Orpheus (the one who, playing his lyre, managed to put Cerberus to sleep, the three-headed dog that protected the entrance to the underworld). In this representation, the condemned man, who played Orpheus, had to tame with music the wild beasts with which he had been locked in a cage -the result, a dismembered body-. The death of Hercules was also recreated, when he puts on the poisoned tunic that causes him such unbearable pain that he asks to be burned to end that suffering. In the recreation of the death of Hercules, the interpreter of the leading role (another convict) was put on a linen tunic impregnated with an inflammable substance (possibly naphtha), and when it was set on fire, it became an authentic human torch. This type of torture and death was called "the annoying tunic". Although it was Nero who perfected the method, when he used it with the Christians whom he had accused of burning Rome in 64, the Law of the XII Tables already stipulated the penalty of being burned alive (ad flammas ) for arsonists.

Torches of Nero (1877) – Henryk Siemiradski

And as in all ancient societies, where women had a secondary role and were subject to the will of men, they had it worse. Although over time the prohibition on drinking wine was relaxed and women were able to enjoy the pleasures of Bacchus, in the origins of Rome, women were prohibited from drinking wine. And for this, the husband used the breathalyzer of the time, the ius osculi (the right to kiss). The husband, when he got home, kissed his wife on the mouth to check if she had drunk wine (no affection or love). Except in the event that the wine had been prescribed by a doctor, because wine was also used for medicinal purposes, the punishment that the wife who had tested positive would receive was a beating, repudiation and even death. According to Pliny the Elder, women convicted of this type of "crime" were to be locked in a room in the house and allowed to starve to death. But all was not lost, the wife could request the "counter-analysis" which, unfortunately for her, was the responsibility of the relatives of the accusing party. The wife had to encourage the husband's relatives who would surely confirm her positive. The Roman writer Valerio Máximo "justified" the reason for punishing this crime:

Any woman who is greedy for wine closes the door to virtue and opens it to all vices.

Of course, Roman legislation also tried to protect the honor and decency of women. Well, but only that of married women, widows and virgins, because the rest were supposed to lack these conditions. The fact of touching a woman, addressing her with some off-color words and even giving her a simple compliment that the recipient could interpret as vulgar or offensive, carried a fine whose amount depended on the social status of the "victim". So how did the Don Juans of the time get it on? Very carefully so as not to be offensive or tiresome and, above all, with a good bag of coins in case the method used was not very subtle or the chosen woman considered that you were not a man for her. A detail that determined decency, and that put you on alert, was that married women, widows and virgins only went out with a male companion (comes ), whether it was a member of his family or even a slave. So, if she didn't have food, you could risk it because she is not supposed to be among the groups of women protected by law.

So squared were these Romans, that they had regulated even suicide. In Rome, suicide was not considered a crime or a sin against the gods, and, in certain situations, it was considered justifiable and pragmatic, as in the case of important figures to avoid public execution and preserve their dignity. However, suicide was explicitly prohibited for slaves, legionnaires and those accused of a crime punishable by death. The slaves, being the "property" of their masters, had no decision-making capacity and, moreover, their death was an injury to the interests of the masters. The soldiers who committed suicide were proclaimed traitors or deserters and all their assets were confiscated in favor of the Republic or the Emperor of the day (and the family was left with nothing). In the case of the defendants, it was also a financial issue, since if they committed suicide before trial, no legal action could be taken to confiscate their property. Logically, faced with a foreseeable death sentence, the defendant preferred to take his own life and, at least, his family was not left with nothing. Until Emperor Domitian arrived and decreed that if they committed suicide before the trial they would also lose all their property.

And what about the rest of the citizens of Rome? Well, according to what the historian Tito Livio and Valerio Máximo tell us, if someone voluntarily wanted to end his life, he had to ask the Senate for permission, explaining his reasons. His case and his motivations were studied, and if it was considered that he was amply justified, it was authorized and even poison was provided free of charge. In case of not being sufficiently motivated, it was about giving solutions and convincing the suicide. If he proceeded without the pertinent authorization, he was buried in a common grave without honors and lost all the properties.

And speaking of poison, in Rome it was thought that women compensated for their lack of strength with dissimulation and betrayal, and that is why poison was attributed to them as their preferred weapon. According to Livy, in 331 BC a mysterious plague broke out that mysteriously attacked men. After subsequent investigations, it was found that the plague in question was nothing more than massive poisoning of women fed up with their husbands. Some 170 women were accused of poisoning, but none reached the level of Locusta, a slave who, thanks to her art in the knowledge and treatment of certain lethal substances, passed into the service of Agrippina, the wife of Emperor Claudius. Agrippina knew how to manage her husband to adopt Nero, the fruit of a previous marriage, and to name him her successor, even leaving aside her own son, her Briton (son of her previous marriage). she with Valeria Messalina). When the relationship between Claudius and Agrippina began to deteriorate, she feared for Nero's succession and decided to act. Following the advice of her particular poisoner, Locusta , Agrippina managed to strain amanita phalloides —which the taster was lucky not to taste— on a plate of mushrooms that the emperor was about to eat. Claudius died in the year 54 without modifying Nero's appointment as his successor. Agrippina's first present to the new emperor was Locusta. A few months later, Nero made his first charge to the poisoner:the death of Britannicus. This time the staging would be a great banquet offered by Nero in honor of her half-brother and for which Locusta prepared a poison composed of a mixture of arsenic and sardony. She offered the taster an innocuous broth, previously overheated, which she had to cool with water... in which the poison was. After the success of the poisoning, Locusta became the official poisoner and even set up a school where she instructed various apprentices and experimented with new poisons.

In this way, Locusta had tied her future to that of the emperor. With the latter's death without succession, the Senate appointed Galba as the new emperor. From that moment on, Locusta's fate was sealed. She was found guilty of more than 400 deaths by poisoning and sentenced to death…a terrible death.

Galba ordered that she be publicly raped by a trained giraffe and subsequently butchered by wild animals. Or so it is told...

And we leave the most… most undignified death for last:the crucifixion. Rome reserved crucifixion primarily for crimes against the state. A form of publicity lesson against agitators and rebels to the Empire. Of course, as a classist and hierarchical society, it was also taken into account at the time of executions, because crucifixion was a prohibited practice for Roman citizens sentenced to death. In addition to the humiliation of being exposed to the elements and public view, it was necessary to add that a slow and painful death, which could last for several days. And although we usually think that the victim was fastened with nails, the usual thing was simply to tie him with ropes, faster and more practical, since it was easier to raise and lower them. We have an example in the most famous slave rebellion, when the 6,000 men that Crassus captured, including Spartacus, were crucified on the Appian Way from Capua to Rome as a macabre warning to any slave who thought he might challenge the power of the slaves again. Republic.

And as the finale of this criminal tour of Ancient Rome, we will go to the arena of the Colosseum, where, with the excuse of any celebration, free shows were organized where fun was guaranteed... if you had the stomach to endure it. A day in the amphitheater was divided into three sessions:in the morning, the venationes took place , or animal hunts, at noon was the time for the executions of those sentenced to death by damnatio ad bestias (the condemnation of the beasts) and, in the afternoon, the gladiatorial combats, the favorite spectacle of the Romans.

With the passage of time, the hunts of beasts became more sophisticated, and they went from hunting native animals, such as wild boars or deer, to more exotic beasts never before seen in Rome. It was a way of showing that the Empire was expanding into unknown lands. Wild animals were released into the arena and hunters (venatores ) were in charge of hunting them, usually with spears. The poet Marcial tells that during the inaugural games of the Colosseum, in the time of Emperor Titus, which by the way lasted 100 days, 9,000 wild animals were sacrificed. Some of these beasts were also used in the next show, that of executions, for example for parricides and, depending on the time, for Christians. The poor wretch in question was tied to a post in the middle of the amphitheater and one of these pretty kittens (or bulls or whatever) was released to carry out the death penalty. If the animal was not up to the job or did not look very appetizing, an assistant stood behind the condemned man and shouted or moved him to get his attention. Animals captured from all corners of the Empire came to the amphitheaters:tigers, bears, panthers, wolves, hyenas, crocodiles, bulls, lions, bison, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses... there was everything. And since the Romans were innovative, fights were also organized between animals, usually of different species.

But this animal cruelty was not only focused on wild animals, domestic animals also suffered. In fact, do you know why on July 18 the Capitol guard dogs were sacrificed? I'll tell you... On July 18, 390 B.C. the Gauls, led by their leader Brennus, massacred the legions at the Battle of the Alia River, very close to Rome. The survivors of that disaster reached the City, and ran to take refuge on the Palatine Hill without thinking of closing the doors. Thanks to such negligence, the Gauls entered the streets of Rome with blood and fire. The remnants of the militia and the citizens who were able to escape the looters took refuge in the Capitol, while the Gauls looted the rest of the city thoroughly. Legend has it that the Romans thwarted a night attack by the Gauls thanks to the warning of the geese from the temple of Juno, who woke up the guard and prevented the Capitol from being taken. After too much time of siege without obtaining anything and with the legions approaching Rome, Breno negotiated with the Romans a ransom to liberate the city. That bitter day of July 18 was marked in Roman citizenship for generations. Every anniversary of the looting, the Capitol's guard dogs were crucified as punishment for their neglect. Those executions had some luxury spectators. The geese from the temple of Juno, the only ones that alerted the people of the Gallic attack, were brought in front of the crosses and perched on purple cushions.

And, now, before the main course and so that everything is spotless, dozens of slaves were busy covering the spilled blood with more sand and removing the remains of animal bodies and those sentenced to death. With everything clean, the trumpets sound, the spectators stand up and watch the triumphal entry of the retinue of gladiators who are going to fight. First of all, I'm sorry to say that gladiator fighting itself is a degeneration. And I explain. The origin dates back to the time of the Etruscans, when this type of combat between prisoners was held to honor the death of a notable character. A funerary ritual that became a playful show. And already put, later the fight between animals or the one of men against animals were added, anything so that the show did not decline. Show must go on . And even though these shows were bloody, nothing to do with gladiator movies or series. And I remember, for example, the series Spartacus, blood and sand , with a staging that is quite faithful to the direct and explicit style that prevails today in this type of epic production. Just like we saw in 300 (which he blatantly copies) or in the British Centurión Liters and liters of blood of different thicknesses are poured without the slightest hesitation, accompanied by the occasional morbid dispute and a lot of turgid meat in motion. As an extra ingredient to so much violence, the risque scenes sneak in between so much sweaty muscle and blood everywhere, some appropriate and even appropriate, but others perhaps not very credible. If you are shocked to see how a slave gropes her mistress while another stimulates her master during a normal conversation, or you find it unpleasant to see nudity, coyunda, blood and viscera gushing out, you can opt for the series Roma , a BBC/HBO co-production, which is more believable.

The reality is that most of the fights were at first blood or with the possibility of forgiveness by the emperor or the editor of the show, only on rare occasions was a fight to the death. You have to think that it was a business:the editor who organized and financed the fights, to win the favor of the people, keep them happy or get the votes for some position in the judiciary, rented the lanistas (owners of the gladiatorial schools) the luchadores que iban a combatir y, lógicamente, pagaba por ello. Si era a muerte había que pagar mucho más, porque un gladiador muerto era un luchador menos que el lanista podía alquilar para otros espectáculos. Así que, para amortizar los gastos (alojamiento, alimentación, atención médica o el entrenamiento) interesaba que peleasen en muchas ocasiones para que fuese un negocio rentable. Es más, incluso había un árbitro en las luchas. Después de realizar el sorteo de las parejas que iban a enfrentarse y de hacerse las correspondientes apuestas, en la arena se quedaban los luchadores y los summa rudis , una especie de árbitros que velaban por el cumplimiento de las reglas –fair play-. Estos jueces, normalmente prestigiosos gladiadores retirados, vestían túnicas blancas y llevaban espadas de madera (rudis ) con las que señalaban movimientos ilegales, paraban el combate si algún gladiador era herido o los incitaban a la lucha golpeándolos si no le ponían muchas ganas. Y aún había más sorpresas, porque tampoco todos eran esclavos, prisioneros de guerra o criminales obligados a luchar en la arena, también había gladiadores profesionales:los auctorati, hombres libres que luchaban por el dinero y la gloria. Se podría decir que su profesión era la de gladiador. Aunque gozaban de la admiración popular, convertirse en gladiador conllevaba la pérdida de los derechos políticos, pero pensándolo bien, era mucho mejor ser gladiador que legionario:cobrabas mucho más, te exponías menos y podías conseguir la admiración popular. ¿No os parece?

Así que, habría que quitar algo de salsa de tomate a las películas de gladiadores, pero donde no habría que quitarle ni una gota, porque eran espectáculos mortales de necesidad, era en las naumaquias (que se podría traducir por «batallas navales»). Serían como una mezcla entre la película Battleship y el juego de mesa “Hundir la flota”, pero sin efectos especiales, en tiempo real y a tamaño natural. La primera de la que se tiene conocimiento la organizó Julio César, y su sucesor, César Augusto, quiso superar al maestro recreando en el año 2 la batalla naval de Salamina, la que enfrentó a griegos y persas. Se excavó un estanque de 1.800 pies de largo y 1.200 de ancho [unas 18 hectáreas] que se comunicó con el Tíber con un canal. Una vez terminado, se abrió la presa y las aguas del río inundaron el estanque a modo de lago artificial. Se cuenta que tomaron parte en ella 30 naves, entre birremes y trirremes con espolones, y un número aún mayor de barcos menores. A bordo de estas barcos combatieron, sin contar los remeros, unos 3.000 hombres.

Un vuelta de tuerca se la darían los emperadores Tito y Domiciano, cuando celebraron naumaquias en el Coliseo inundando la arena. Por el tamaño del recinto, en estas representaciones había menos actores y las naves apenas podían virar. Así que, los espectadores tenían que conformarse con el abordaje y la lucha cuerpo a cuerpo. Debido a las dificultades de inundar el Coliseo y el elevado coste de construir lagos artificiales o anfiteatros adecuados, las naumaquias fueron cayendo en el olvido. Y en estas naumaquias, es donde se pronunció la frase ritual que, erróneamente, hemos atribuido a los gladiadores que luchaban en la arena…

Ave César, los que van a morir te saludan.

El historiador Suetonio fue el primero, y el único, que hizo referencia a esta frase cuando los participantes en una naumaquia se dirigieron al emperador Claudio en el combate naval que organizó en el lago Fucino. No es de extrañar que pronunciasen esta sentencia de muerte, pues combatientes y remeros eran prisioneros de guerra o condenados a muerte. Su destino era ahogarse o morir matando. Aquí moría hasta el apuntador.

Y ya que hemos hablado de él, dejadme terminar recomendando la novela Espartaco , de Howart Fast, y la posterior joya cinematográfica de Kubrick, Por cierto, Howard Fast la escribió en 1951 estando encarcelado por su militancia en el Partido Comunista de Estados Unidos. Un hombre hecho a sí mismo y prolífico escritor, debido a sus ideas políticas fue machacado por la administración estadounidense, llegando a boicotear la publicación de varios de sus libros. Espartaco es una alegoría a la lucha por la libertad que muestra la vileza de una sociedad caprichosa y opresora que vive del indefenso y el ignorante. Muchos de sus detractores denunciaban que Fast equiparaba la antigua Roma a los Estados Unidos. Sirva de referencia su dedicatoria:

Para que los que me lean se sientan con fuerzas para afrontar este incierto porvenir nuestro y sean capaces de luchar contra la opresión y la injusticia.

Ahí queda eso… y hasta aquí esta historia.

Fuente:Historia Criminal (Podimo)

Ya a la venta en Amazon mi último libro: