Who hasn't told ghost stories by the light of a campfire? Possibly the image of a group of humans exchanging ghost legends is as old as that of a group of hunters dressed in furs, boasting of having killed a mammoth with mere insults and having slept with all the women of the tribe. After all, and well thought, in both cases they are "ghost stories". But to reach the state of wandering spirit, someone must first die.

For the Mesopotamians, death was something very important. Humble graves were called Kimah (exalted place) and those of the rich Ekal Tapsuhti (rest abode). They believed that when a person died, a part disappeared, such as bones or meat, but another remained. It should be noted that this part that remained was not like the soul of the Judeo-Christian culture, since it continued to have corporeity, although it had less presence or density than the normal body. That kind of spirit, which the Mesopotamians called Gidim or Etemmu , went on to reside in the World of the Other Side (Irkalla) , but for this he had to be fired with the corresponding rites. In some Sumerian cities the deceased was buried in a tomb, and in others under the floor of the main room of the house. If the address was changed, the remains had to be moved to the new location. They were buried with little trousseau, just a favorite or sentimental object, since it was much more important that they were offered food and drink. The minimum acceptable was to pour water through a hole that the tombs used to have, and the desirable thing was to add, from time to time, something more tasty. The reason is that in the World on the Other Side In that world of the dead, there was no food. Contrary to what is thought, they did not imagine it below the earth, but rather it came to be a world parallel to ours and, to a certain extent, coexisting, but without flavors, smells, colors, or even television. A disgusting place, in short.

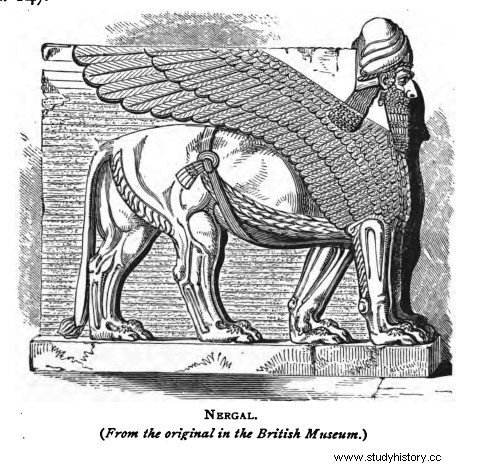

A particularly horrible form of punishment was to deny the executed the burial rites. Those who committed especially serious crimes not only had to go through a series of tortures each more sadistic, but their body was burned and their ashes scattered on the outskirts of the city. In Nippur, for example, this was done at a gate known as "that of the Sexual Impures." Whoever received rites and burial went through the seven gates of the World on the Other Side , and was received by the infernal gods in the Kur . But there was no trial, no reward, no punishment. He didn't care if he had been a good person or a bad person. The gods only informed him of the rules of his new home and assigned him an abode. If he had made the ball long enough, he could live inside Gazer's fortress , home of Nergal and Ereshkigal , with which he could access the leftovers from the kitchen and wink at the devils and / or devils of domestic service.

A person who did not receive funeral rites, who died of hunger and thirst, or drowned, or in a field alone, could not enter the Irkalla , and became an Etemmu Murtappidu , who came to be like a ghost with a very bad grape willing to take revenge on everything and everyone, but especially those who had not offered him the rites. These types of ghosts were very dangerous, because by not entering the Irkalla They could attack at any moment. The others, those who had entered but had some pending issue, could only return one day a year. In the month of Neizigar (Sumerian) or Abum (Akkadian), which would correspond to our August, was celebrated on Day of the Dead, under the Kispum ceremony . Since the dead could leave their world on that day, they were treated in style. The "chair of honor" was installed in the main place, although in humble homes it was a simple stool, which used to be inherited by the firstborn (rarely by the firstborn) (* ). Before her the best food and drinks were placed and the ancestors were remembered by their names until the third generation. The others were treated as "relatives". This was so important that there were kings who falsified their genealogy in that ceremony. Thus, for example, the Assyrian usurper Shanshi Adad I offered a kispum to the old Akkadian ruler Sargon of Akhad , who had lived four centuries before and was considered an example for kings, making believe that he was "descendant".

Kispum

How did an angry ghost attack?

Well, it entered the body through the ears, since it was believed that the Etemmu he had some kind of “flavor” and, therefore, through the mouth they would discover him. The most appropriate time was during sleep, because for the Mesopotamians the world of dreams was real. Once inside the body they produced migraines, fevers, bad breath, insomnia, nightmares and all kinds of discomfort. How could this be avoided? First of all discovering the attacker. A ghostly body could be perceived in sunlight as a kind of faint colorless shadow. If the victim was successfully possessed, the ghost could only be expelled by an exorcist priest. If someone discovered a ghostly shadow lurking, the best thing he could do was invite the ghost into his house and offer him a feast, since a divine rule ordained that hospitality be sacred. A revenant ransacking your pantry couldn't bother you.

Were Mesopotamians fond of ghost stories?

You are right. In fact, apart from several other isolated and fragmented references, one of them has been preserved almost entirely:the Myth of the Newlywed and the Apparently . With this we have again a very modern idea of Sumerians, Assyrians and Babylonians, and we can imagine them narrating the vicissitudes of the poor bride in the light of a bonfire with some marshmallows in her hand. Therefore, if you have the idea that a ghost is stalking you, follow the Sumerian advice and offer him a fresh beer (Sumerian, of course) and some delicious olives. You'll save yourself an exorcism.

(* ) It does not seem that this preference was due to machismo, but rather due to the division of tasks. Thus, for example, in the same way that the man was the one who directed the Kispum ceremony, it was the woman (specifically the daughter-in-law or the eldest daughter) who directed the burial.