The demand for women's right to vote appears linked from its origins to the thought and action of groups of women who became aware of the unjust situation to which they were subjected by a patriarchal social structure that ignored them. The achievement of social, legal and economic rights was a long process that reached its peak well into the 20th century in Western societies. The battles, however, have not yet achieved final victory, there are many flanks to attend to, but it is also undeniable that progress has been great.

1. Notes on the origins of the feminist movement.

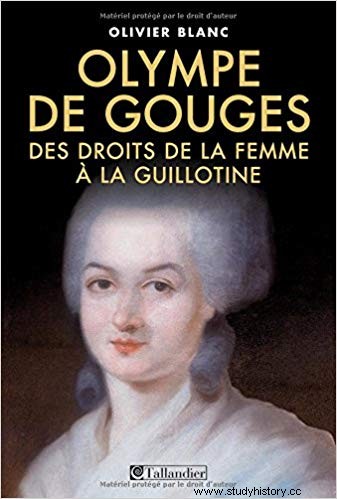

Feminism, understood as a doctrine that promotes equal rights for women, finds its precedent in the Enlightenment thought of the eighteenth century. The French Revolution of 1789 allowed women's petitions to reach the revolutionary political institutions; personalities such as Condorcet or Olympe de Gouges write about it, the latter in her Declaration of the Rights of Women and the Female Citizen , published in 1791, makes a clear plea in favor of recognizing women the same rights as men. A marginal phenomenon, without a doubt, confined to cultured environments, but a first theoretical step.

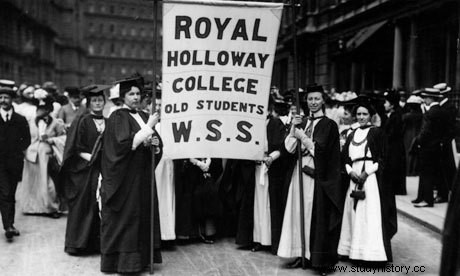

The influence of these texts did not take long to reach Great Britain, but it would still take a century for the first feminist movements, linked to liberalism or political socialism, to materialize. In all places, and the same will happen somewhat later in Spain, the feminist claims were aimed at obtaining educational and legislative improvements on economic and labor rights, with little being said about the right to vote. In 1866 John Stuart Mill presented the first motion in the British Parliament in favor of women's suffrage, requests that would be repeated years later with negative results. Despite these political setbacks, suffrage gained a social base and in 1897 the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies was created. It was, then, in Great Britain and almost parallel to that in the United States, where feminist movements and suffrage demands arose better and with more intensity.

In many cases, feminism and suffragism did not constitute autonomous movements but were linked to political parties and unions of all ideologies. At the end of the 19th century and already in the 20th century, numerous countries began to grant the right to vote to women:

| Country | Year |

| New Zealand | 1893 |

| Australia | 1902 |

| Finland | 1906 |

| Norway | 1913 |

| Denmark | 1915 |

| Great Britain | 1917 |

| Soviet Union | 1917 |

| United States | 1920 (in the presidential) |

| Spain | 1931 |

| Brazil | 1935 |

| Uruguay | 1938 |

| France | 1946 |

| Argentina | 1947 |

| Mexico | 1953 (at nationals) |

2. Feminism in Spain until the Second Republic.

Historical feminism must be seen as a plural and diverse social movement that has its own characteristics that are related to the Spanish context of each historical moment and to the experience of very diverse women. The phenomenon of historical feminism must also be understood as a social process of renegotiation of the social gender contract and not only as a movement that seeks to confront the patriarchal system. Feminist manifestations were weak, minority and very moderate during the 19th century.

Until the Democratic administration (1868-1874), the census suffrage established by the various liberal constitutions guaranteed a monopoly of politics to a minority that never exceeded 4% of the population. During the Restoration the system opened up a bit more but left out all the forces that questioned the political system. The levels of political fraud and corruption facilitated the distancing of many social sectors from political participation, such as anarchists. In this context, feminism did not raise political claims, which is why the emergence of a liberal political feminism did not prosper, as it had happened in Great Britain or the United States. However, Spanish feminism took other paths, acting in the spaces in which the female presence was common, linking, already later, at the end of the century, to political parties or movements –anarchism, Lliga Regionalista Catalana– or to isolated personalities –Emilia Pardo Bazán.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the variety of modalities of feminism is highlighted. Thus, Catalan feminism is structured around a patriotic discourse linked to Catalan Solidarity. He accepts politics as a masculine patrimony and understands suffrage as something proper to men. They underline, however, the role of women in shaping a Catalan cultural identity, which is why their claims are aimed at claiming a role for women in the cultural and educational world. However, despite its conservative nature, Catalan feminism promoted the social and cultural rights of women.

Similar was the position of the National Association of Spanish Women (ANME), created in 1918, by adopting a Spanish nationalist discourse in which women play the role of inculcator, together with the school, of the national principles for what should count with all the necessary means. Although he intended to distance himself from political radicalism and remain in the political center, his program has a conservative slant. Shortly before, in 1912, the Socialist Women's Association had been created in Madrid, linked to the PSOE.

The emergence of these associations should be interpreted as a symptom of social change and an attempt to revise a deeply rooted patriarchal system. And although his political and suffragist demands will take time to appear, his interest in female education and social reforms were a clear manifestation of what was said. From the twenties, Spanish feminism incorporates political demands. The ANME program raised relevant demands:reform of the Civil Code, abolition of prostitution, right to engage in liberal professions, equal pay,... The association never had the support of any political party, a fact that could have influenced its becoming in political party in 1934 with the name of Independent Feminist Political Action, lasting as such until 1936.

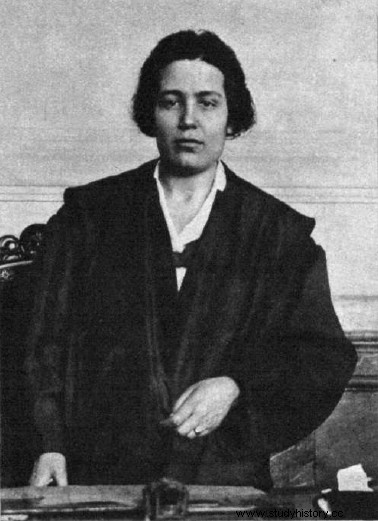

In the late twenties and early thirties, the political changes that were taking place in the country promoted a liberal political feminism that demanded suffragism, based on the principle of equality between men and women. Women like Clara Campoamor, Margarita Nelken or Victoria Kent took on this approach. However, it should be noted that even at the time of the suffrage debate in the Cortes, suffragism was a very small movement in Spanish society, although it had figures as exceptional as those already mentioned and others less well known.

3. The achievement of women's right to vote in the Second Republic.

The Second Republic represented a unique opportunity to carry out the democratic proposals that had been outlined by personalities and feminist groups. Important feminist voices participated in republican political life, although through the different parties:María Martínez and Matilde Huici with the PSOE; Elisa Soriano and Clara Campoamor with the Radical Socialist Party; Carmen de Burgos with the Republican Left, etc.

The first step to favor the inclusion of women in politics with the same rights as men was the Decree of May 8, 1931 that declared women eligible in the next elections to the Constituent Courts that would be held on June 28. Two deputies were elected in them -Clara Campoamor (Radical Socialist Party) and Victoria Kent (Republican Left) out of a total of 465 deputies.

Clara Campoamor was elected rapporteur for the constitutional commission in charge of drafting a new Constitution and actively participated in the drafting of the articles referring to women's rights. Thus, article 34 of the project established the equality of electoral rights to all citizens regardless of their sex as long as they were over 23 years of age.

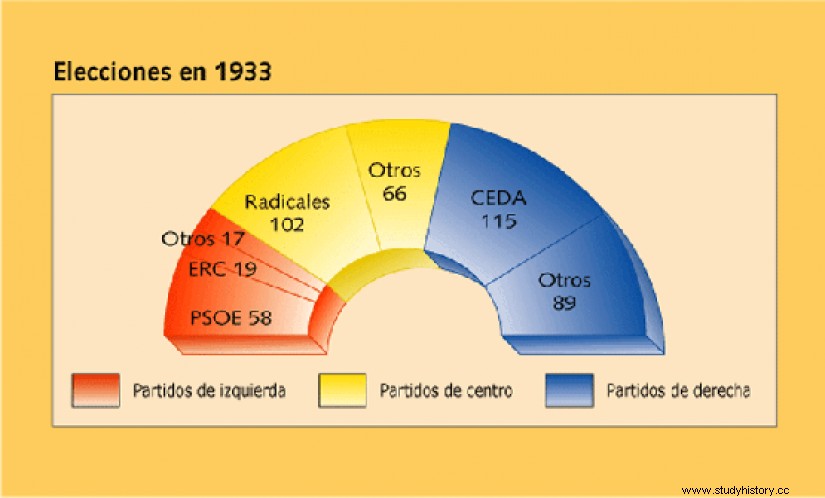

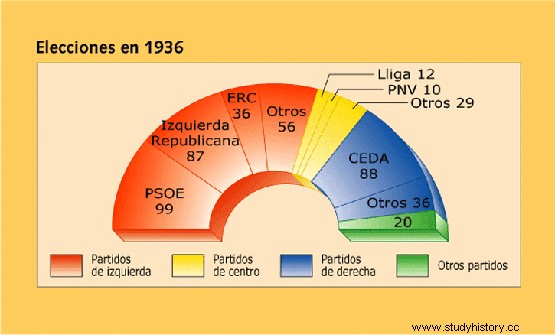

Interestingly, the right-wing deputies, who continued to see the role of women exclusively in the family framework, see in the female vote an opportunity to vary the electoral results since they thought that women were highly influenced by the Church and that they would vote more measure to conservative formations. On the contrary, the Republican and left-wing groups expressed their fears regarding its convenience since they thought that the female vote was more conservative. And while it is true that these predictions seemed to come true in the 1933 elections, they did not in the 1936 elections, which shows that the results depended more on the respective alliances between parties than on the direction of the female vote.

The hard battle given by Clara Campoamor, even against Victoria Kent, in favor of postponing women's right to vote, managed to get the article approved with 161 votes in favor and 121 against. Voting in favor was the PSOE –with some exceptions–, the right and small republican groups –Catalans, progressives… Acción Republicana, the Radical Socialist Party –to which Campoamor belonged– and the Radical Party all voted against. In this way, the 1931 Constitution included, for the first time in Spain, the right to vote for women. A brief achievement since after the victory of Franco's forces in the Civil War (1936-1939) women once again passed into the background social, political and economic, also subjected to the totalitarian designs of national-Catholicism.

Bibliography.

DeVega, E. (1992). The woman in history . Madrid:Anaya.

Domenech, A. (1985). The feminine vote. History Notebooks 16 ,163 .

Duran, P. (2007). The female vote in Spain . Assembly of Madrid.

Franco Rubio, G.A. (2004). The origins of Spanish women's vote. Space, Time and Form, Series V, ti.-Contemporary, t , 16 .Retrieved from https://www.ucm.es/data/cont/docs/995-2015-01-09-sufragismo.pdf

Nash, M. (1995). feminism. Current World Notebooks , 47 .

Nash, M. (2005). The learning of historical feminism in Spain. Web document:http://www. node50. org/mujeresred/historia-MaryNash1. html/yahoo. is .Retrieved from http://www.xateba.es/images/PDF/Recursos/historiamary.pdf