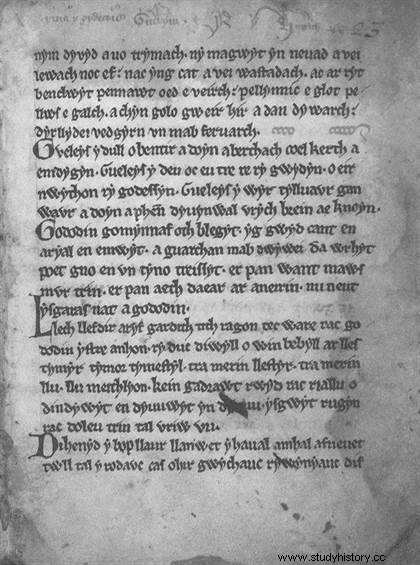

The Arthurian Legend (or Arthurian Cycle) is a series of works in several languages written from the 11th century and which tells the story of King Arthur and his knights. Sung from the VI

e

century in epics in the Welsh language, it culminates as early as the ninth

th

century to a prolific literary flowering presenting the history of Great Britain around the facts of a warrior king and his court. Thus nourishing the most prestigious literary creations, the legend of King Arthur became one of the richest and most lively genres of the medieval West. It is thus not the work of a single author but of multiple writers seeking from generation to generation to add their contribution or their adaptation.

The Arthurian Legend (or Arthurian Cycle) is a series of works in several languages written from the 11th century and which tells the story of King Arthur and his knights. Sung from the VI

e

century in epics in the Welsh language, it culminates as early as the ninth

th

century to a prolific literary flowering presenting the history of Great Britain around the facts of a warrior king and his court. Thus nourishing the most prestigious literary creations, the legend of King Arthur became one of the richest and most lively genres of the medieval West. It is thus not the work of a single author but of multiple writers seeking from generation to generation to add their contribution or their adaptation.

Of the historical creation of the Arthurian legend

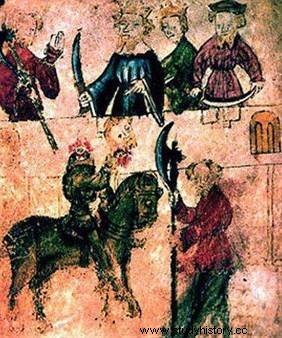

The first representations of the Arthurian legend date from the VI e century. Let us quote the text of the cleric Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae , generally considered the oldest or still in the IXth century, the Historia Britonum falsely attributed to the chronicler Nennius. Nevertheless, these writings only expose quite lapidarily the warlike facts of a certain king who is still anonymous in Gildas and it is necessary to wait for the XII e century for the composition of the first truly founding text of the legend. Bishop close to the Plantagenet royal family, Geoffrey of Monmouth book in 1138 his Historia regum Britanniae , chronicle in Latin recounting the main historical events of Great Britain. From the origins to the civilizing Romans, the clerk then exposes the lineage of kings and of which the most admirable among all is none other than Arthur. The success of his text is immediate:the some two hundred European copies which have come down to us and which must represent only a small percentage of the total number of medieval copies created testify to the enthusiasm for this myth on the way to crossing the elitist barrier. of the Latin language.

Indeed, observing the enthusiasm for this legend, King Henry II Plantagenet decided to recover it politically at his profit in order to ensure the legitimacy of his line on the throne and to exacerbate his rivalry with the King of France, of whom he is the vassal. And faced with the Capetian sovereign, considered the ancestor of the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne, Henry II knows that he lacks prestige. Moreover, he still clashes with the Saxons, still reluctant to accept the recent Norman conquest (Hastings – 1066) and seeks the support of the Bretons against them.

Indeed, observing the enthusiasm for this legend, King Henry II Plantagenet decided to recover it politically at his profit in order to ensure the legitimacy of his line on the throne and to exacerbate his rivalry with the King of France, of whom he is the vassal. And faced with the Capetian sovereign, considered the ancestor of the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne, Henry II knows that he lacks prestige. Moreover, he still clashes with the Saxons, still reluctant to accept the recent Norman conquest (Hastings – 1066) and seeks the support of the Bretons against them.

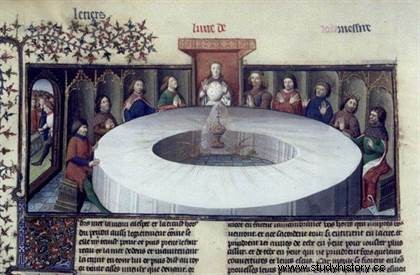

But wouldn't King Arthur be the one who allied himself with the Breton Merlin to repel the fearsome Saxons? King Plantagenet then decides to confiscate the legend in order to present himself as the legitimate heir of King Arthur and he entrusts to the Anglo-Norman cleric Wace, the "mise en roman", in other words the translation of the Latin text Geoffrey of Monmouth into the language vernacular, in this case in French. Wace then signs the Roman de Brut intended for a wider audience. And if he recovers the basic elements of his predecessor, definitively laying the foundations of the legend, he does not hesitate to invent new motifs such as the Round Table and opens the myth to romantic literature.

Christians of Troyes and Christianization

Often wrongly considered the creator of the Arthurian novel, Chrétiens de Troyes nevertheless presents himself as the one who gave it a new literary dimension. If the figure of King Arthur is mentioned in some lays of Marie de France, it is truly Chrétiens de Troyes who contributes to the extra-insular development of the legend in the second half of the twelfth century. century. Poet novelist, he lived at the court of Champagne with the countess Marie, daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine, then he ended his life in the service of Philippe d'Alsace, count of Flanders.

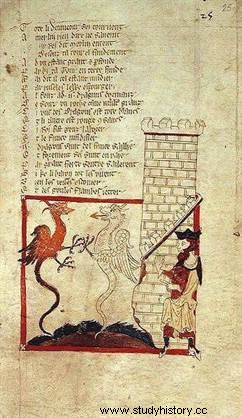

Author of five "Breton" works:Érec et Énide ; Cligès ; Lancelot, or the Knight of the Cart ; Yvain, or the Knight of the Lion ; Perceval, or the Tale of the Grail , it sets out stories centered on the court of King Arthur who no longer appears as the main character. And more than stories of battle, Chrétiens de Troyes develops the private life of its heroes focusing at least as much on love and the marvelous as on warlike exploits. In his latest novel, he introduces the mysterious religious motif of the Grail without us knowing what dimension he intended to give to the holy object. Indeed, death interrupts him and leaves his work unfinished but not devoid of successors.

At the beginning of the XIII e century, a certain Robert de Boron thus inscribes the Arthurian legend in a more Christ-like dimension around the theme of the Grail. Around the writing of three novels in verse, he gives a resolutely Christian interpretation to the myth of the Grail, the Round Table becoming for example a reproduction of the Table of the Last Supper. From then on, the court of King Arthur became a Christian court and these knights Christian rather than Celtic heroes, which was not without causing a certain upheaval in their values. The introduction of this religious dimension then leads the Arthurian novel on two different paths:on the one hand, verse novels focusing on the marvelous and magical, on the other hand, prose novels which increasingly develop the religious dimension.

Novels in prose, novels in verse, European novels

Until then, Arthurian romances were written in verse, a literary style considered in medieval times as that of fiction. In order to better legitimize and anchor the legend in reality, the literature devoted to it adopts prose. Indeed, Romanesque prose, imitating the prose of Latin chronicles thus claims to reproduce the ancient chronicles of Arthur's time, the veracity of which cannot be doubted. It is then the time of literary sums, a kind of encyclopedic compilations, to which the Arthurian legend does not escape.

Thus, around 1225-1230, appears the cycle of Lancelot or tale of the Grail , also called the "Vulgate cycle ", anonymous. More than two thousand pages divided into five sections retrace the epic of Arthur's kingdom from its origins to the death of the king, while giving a central place to The Quest for the Holy Grail . This sum, considered a monument of medieval literature, was very quickly reworked and followed by others. For example The Post-Vulgate Cycle , still anonymous, which exposes the same story but with another darker overall vision.

At the same time, the Arthurian legend continues to be enriched with novels in verse, taking over from the unfinished work of Christians of Troyes. And until the end of the XIV

e

century, many authors have tried their hand at this genre. The columnist Jehan Froissart thus composed the longest novel in verse:Meliador . But more than an opposition between prose and verse, it is a profusion of European versions that is spreading. Going beyond the framework of the kingdom of France, the Arthurian novels are translated and adapted into different languages:German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Czech, etc. We can even note the existence of a version in Provençal.

At the same time, the Arthurian legend continues to be enriched with novels in verse, taking over from the unfinished work of Christians of Troyes. And until the end of the XIV

e

century, many authors have tried their hand at this genre. The columnist Jehan Froissart thus composed the longest novel in verse:Meliador . But more than an opposition between prose and verse, it is a profusion of European versions that is spreading. Going beyond the framework of the kingdom of France, the Arthurian novels are translated and adapted into different languages:German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Czech, etc. We can even note the existence of a version in Provençal.

However, the most vivid late medieval development of Arthurian themes took place in Britain. On the one hand, the French novels are translated into English, on the other hand the English writers reclaim the legend, considering that it belongs to them by right and give it a new breath. In the 15th th century, Sir Thomas Mallory resumes in a new immense sum both the French heritage of the Lancelot-Graal , than its English sequels and reworkings. It is mainly thanks to Mallory whose work was printed in 1485 that the English literary heritage of the Arthurian legend was saved and restored.

The timeless Arthurian legend

What to remember from what was originally just a tale of the warlike exploits of a king in Britain ? The Arthurian legend became one of the most popular in the medieval West to the point of being considered a literary genre in its own right. An inexhaustible source of inspiration for medieval authors, it still appears as alive today. Indeed, if the Renaissance eclipsed the Arthurian genre in all languages, it was only to better rediscover it in the 19

th

century with the romantic movement and even more in the XX

th

century by going beyond the framework of literature with cinema and beyond.

What to remember from what was originally just a tale of the warlike exploits of a king in Britain ? The Arthurian legend became one of the most popular in the medieval West to the point of being considered a literary genre in its own right. An inexhaustible source of inspiration for medieval authors, it still appears as alive today. Indeed, if the Renaissance eclipsed the Arthurian genre in all languages, it was only to better rediscover it in the 19

th

century with the romantic movement and even more in the XX

th

century by going beyond the framework of literature with cinema and beyond.

Some medieval texts

- Christians of Troyes, Complete Works, Paris, Gallimard, 1994.

- The Arthurian legend, Danielle Régnier-Bohler (dir.), Paris, Robert Laffont, 1999.

- Robert de Boron, Merlin:Roman du XIIIe siècle, Paris, Flammarion, 1989.

Bibliography

- Martin Aurell, The Legend of King Arthur, Paris, Perrin, 2007.

- Anne Berthelot, Arthur and the Round Table. The strength of a legend, Paris, Gallimard, 1996.

- Michel Zink, French Literature of the Middle Ages, Paris, PUF, 1992.