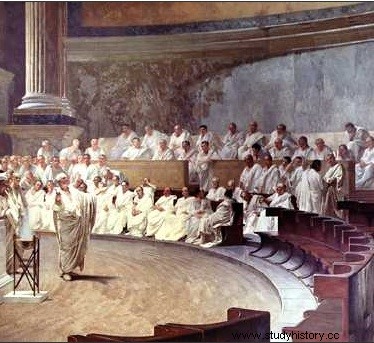

“Ancient Rome is the term given to the civilization which developed, in Antiquity, in Italy and then all around the Mediterranean, submerging the Greek and Carthaginian civilizations. This long and tumultuous period has its roots in mythology, from Romulus to Marius (8th century BC - 2nd century BC), including the duel between Hannibal Barca and Scipio l 'African. It sees a succession of royalty, first mythical, then Etruscan with the Tarquins before seeing the birth of the famous Roman Republic and its famous Senate (510 BC to 27 BC).

“Ancient Rome is the term given to the civilization which developed, in Antiquity, in Italy and then all around the Mediterranean, submerging the Greek and Carthaginian civilizations. This long and tumultuous period has its roots in mythology, from Romulus to Marius (8th century BC - 2nd century BC), including the duel between Hannibal Barca and Scipio l 'African. It sees a succession of royalty, first mythical, then Etruscan with the Tarquins before seeing the birth of the famous Roman Republic and its famous Senate (510 BC to 27 BC).

Ancient Rome and its kings

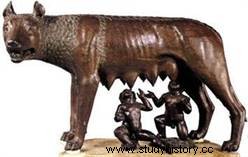

At the time when the Greeks began a veritable diaspora in the Mediterranean basin, tradition fixed the birth of a small city in Latium, Rome, whose first king, Romulus belonged to the legend. The genesis of this Italian city indeed takes place in times that escape history, which is still an unknown literary genre. According to mythology therefore, Romulus and those who are called the legendary kings succeed one another at the head of Rome, each corresponding to symbolic functions theorized by Georges Dumézil in what is called the Indo-European tri-functionality:Romulus and Numa represent in a dualistic way the traditional royalty with on one side respectively the executive power, and on the other the religious function (which the Indo-European kings fulfill in part), Tullus Hostilius symbolizes the warrior force and finally Ancus Martius economic production and social affairs. Alongside this tradition, the ancient past of Rome comes to us through archeology, which makes up for the lack of texts.

The discovery of holes in the ground made to accommodate poles, suggests a habitat from a date close to that transmitted by the legend and also indicates to us a probable agro-pastoral activity, completely in agreement with the life described by Livy about Romulus. Historically, the presence of the Etruscans, a very astonishing and somewhat mysterious civilization in its origin, is attested as early as the 7th century BC. AD, then Etruscan royalty began in Rome in the 6th century with Tarquin the Elder, Servius Tullius and Tarquin the Superb.

The discovery of holes in the ground made to accommodate poles, suggests a habitat from a date close to that transmitted by the legend and also indicates to us a probable agro-pastoral activity, completely in agreement with the life described by Livy about Romulus. Historically, the presence of the Etruscans, a very astonishing and somewhat mysterious civilization in its origin, is attested as early as the 7th century BC. AD, then Etruscan royalty began in Rome in the 6th century with Tarquin the Elder, Servius Tullius and Tarquin the Superb.

If nothing is completely clearly attested concerning the historical veracity of these kings, it is in any case certain that at this date Rome was an Etruscan city, which at the contact with this civilization then developed an urbanism symbolized by the Servian wall (or wall of Servius Tullius), not to mention a whole set of more or less common consumer products, such as typical Etruscan pottery. It was under the domination of the Etruscan king Tarquin the superb that the cult of the divine triad Jupiter, Juno and Minerva was erected on the Capitol. Rome was then a powerful city which dominated Latium through the Latin League formed around it.

Foundation of the Roman Republic

In Roman history a fundamental event then occurs; the deposition of Tarquin the Superb in 509 BC. AD at the instigation of L. Iunius Brutus and the establishment of a new regime, the Republic. The date has been much debated, because at the same time, Athens was driving out the Pisistratids (the tyrants; a form of personal and populist government). Nevertheless, the great historian of Rome, Pierre Grimal, gives credit to it, as this fact must have seemed significant to contemporaries.

In any case, the end of the 6th century and the beginning of the 5th century were marked by a clear decline in Etruscan power in the region. Rome, freed from Etruscan domination, apparently experienced a certain weakening as well as a significant slowing down of Hellenic artistic influences. The new regime in place was based above all on a two-headed executive power, reflecting among the Romans a marked disgust for the power of a single man. Two praetors therefore run the city annually, soon to be replaced by consuls. The religious function of traditional royalty, the origin of which we have mentioned, continues and one of the magistrates is invested with this role.

The rest of the functioning of the city remains unchanged; the Patricians hold matters in hand in the aristocratic assembly of the Senate, relying on the curiate and centuriate comitia. However, Tarquin does not admit defeat and with allies like the inhabitants of Veii and the Etruscan king Porsenna he comes back in force, but he is defeated near Aricia. From 501 BC. J.-C. it is the Latin league which takes the weapons against Rome, pushing the Romans to rely for the first time on a dictator assisted by a master of the militia; this supreme power therefore remains tempered. Victory is won at Lake Régille thanks to the Dioscuri (children of Jupiter), according to legend.

Ancient Rome, a divided society

This is when a completely different type of conflict begins; the confrontation between Patricians and Plebeians. The latter, despoiled during the change of regime which took place almost exclusively to the benefit of the former, think for a time of secession, which shows how deep the divergence could be. But the distribution of the citizens in the new territorial tribes which replace the old ethnic ones gives rise to a plebeian assembly not recognized by the aristocrats, but which nevertheless ends up imposing itself.

At the same time, the centuriate organization of the comitia favored the appearance, alongside the aristocratic cavalry, of a heavy infantry related with a few centuries of lag to the Greek hoplitic reform. The crisis that begins around 451 – 450 BC. J. - C. leads to the drafting of the famous Law of the XII Tables which secularized the right, decreasing in fact the sacerdotal authority of the patrician pontiffs. In the pursuit of this movement, the plebs obtained civil rights (trade, marriage). As early as 471, the Plebs had given themselves inviolable tribunes who counterbalanced the power of the Senate and the principal aristocratic magistrates by their right of veto. In 440 BC. J.-C., the conflict finds its solution with the equality between patricians and plebeians (lex Carnuleia).

The beginnings of expansion

Fortified in its institutions, Rome set out to conquer its lifelong rival; Veii which is submitted in 395 BC. J.-C. and whose looting brings back an enormous booty to Rome. Freed from this dangerous neighbor, the Romans did not enjoy their victory for long. Indeed, a Celtic expedition leads to the sack of Rome in 390. Only the Capitol is spared, the defenders having entrenched themselves there. The Celts, undermined by an epidemic, agree to negotiate; it was then that, faced with the complaints of the Romans, the Celtic chief, Brennos, would have thrown his sword into the scales used to weigh the indemnity, proclaiming “Woe to the vanquished! (Vae Victis).

Fortified in its institutions, Rome set out to conquer its lifelong rival; Veii which is submitted in 395 BC. J.-C. and whose looting brings back an enormous booty to Rome. Freed from this dangerous neighbor, the Romans did not enjoy their victory for long. Indeed, a Celtic expedition leads to the sack of Rome in 390. Only the Capitol is spared, the defenders having entrenched themselves there. The Celts, undermined by an epidemic, agree to negotiate; it was then that, faced with the complaints of the Romans, the Celtic chief, Brennos, would have thrown his sword into the scales used to weigh the indemnity, proclaiming “Woe to the vanquished! (Vae Victis).

Very marked by this attack, Rome nevertheless entered half a century later in a series of conflicts against an Italic people; the Samnites. Between 343-341 BC. AD, then 327-304 BC. AD and 298-291 BC. J.-C. the Romans had to adapt militarily to submit these fierce warrior peoples, who, entrenched in the Apennines posed considerable problems to the Roman civic army equipped in the manner of the Greek phalanxes.

So they perfected the so-called manipulative system; a maniple is a small subdivision of the army consisting of two centuries. These more compact units made it possible to fight on rough terrain and flush out the Samnites. In civil life, this period is marked by the right granted to the plebeians to seek the sovereign pontificate (lex Ogulnia 300 BC) which broke the existing link between aristocracy and religiosity, a fundamental element of distinction until now. between the two “classes” constituting Roman society.

Nevertheless, war rumbled on again. The city of Taranto, allied to the king of Epirus Pyrrhus put Rome in great difficulty. Despite everything, the victories won by the Hellenistic sovereign, passed down to posterity as very costly in human life in his own ranks (a Pyrrhic victory), gave the Romans the opportunity to retaliate with force; from 272 BC. AD Taranto fell.

Rome versus Carthage; the fight to the death

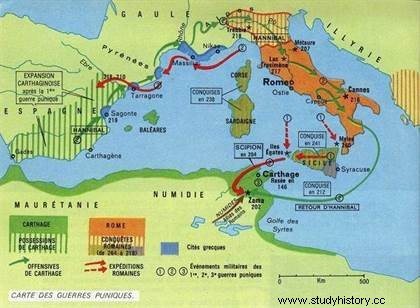

Since 348 BC. BC, Rome had entered into diplomatic contact with the other great power of the western Mediterranean Carthage. The agreement between the two powers was renewed in 306. But Rome, mistress of Italy and freed from Epirote pretensions, and Carthage in full expansion towards the Italian islands, soon came into contact on the occasion of a rather marginal event.; the call of the Mamertines to Rome as they were besieged by the Carthaginians in Messina. The Roman intervention launched the conflict between the two rival Empires in their interests, and in particular about the Sicilian question.

Confrontation, essentially maritime, saw the Romans quickly adapt to this new technique for them. Between 264 and 241 BC. J.-C. the fights raged. Rome gradually prevailed and managed to land an army on Carthaginian soil which was crushed by Hamilcar Barca, the father of the future military genius Hannibal. But, tired of fighting, the Punic city, whose essentially commercial activity suffered enormously from the confrontation, decided to deal with Rome. She lost most of her fleet, Sicily, then Corsica and Sardinia due to inaccuracies in the treaty. She also had to provide a considerable war indemnity, which emptied her coffers and provoked the revolt of her mercenaries. Rome emerged from its success against a recognized power in the Mediterranean Basin and then became a real force on an international scale.

The Second Punic War

However, the harshness of the settlement of the conflict gave rise to a fierce determination for revenge in the Hamilcar family, the Barcides, who carved out an immense domain in Spain, thus taking advantage of the human and metallic wealth of the Iberian Peninsula to prepare revenge. On this date, Rome fortified its position in Italy by fighting the Celts of the Po plain and the Illyrians, on the other side of the Adriatic Sea. A new minor event precipitated the setting in motion of the two rival powers:the taking of Sagunto in Spain by Hannibal against the advice of the current treaties.

However, the harshness of the settlement of the conflict gave rise to a fierce determination for revenge in the Hamilcar family, the Barcides, who carved out an immense domain in Spain, thus taking advantage of the human and metallic wealth of the Iberian Peninsula to prepare revenge. On this date, Rome fortified its position in Italy by fighting the Celts of the Po plain and the Illyrians, on the other side of the Adriatic Sea. A new minor event precipitated the setting in motion of the two rival powers:the taking of Sagunto in Spain by Hannibal against the advice of the current treaties.

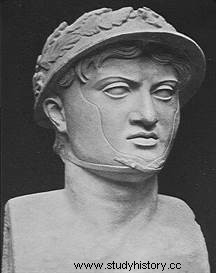

The fall of its ally confronted Rome with the war that the Carthaginian general had carefully prepared. Racing with a motley army made up of Iberians, Celtiberians, Lybian, Numidian and Carthaginian mercenaries, Hannibal crossed the Alps without firing a shot and began a series of spectacular victories. In Tessin and then in Trebia he demonstrated his tactical superiority and opened up the road to the south, towards Rome. On the way, he tricked the consular army sent to meet him by taking it in a gigantic ambush at Lake Trasimeno. The Romans and their allies, trapped, were massacred or drowned.

Hannibal continued on his way, past Rome to the east, pursued by two consular armies whose total strength seems to have reached 80,000 men. With his army of less than 50,000 men, the Carthaginian seemed in great difficulty, cut off from his base and in enemy territory. The Celts and the Italian allies of Rome had shown little enthusiasm for rebelling, and so it was in this seemingly hopeless situation that he entered the Battle of Cannae. Hannibal arranged the front of his army in an arc towards the enemy (composed of Spaniards and Celts), on the wings in a receding column came his phalanxes, and at the end his Carthaginian and Numidian cavalry.

The Romans made no tactical subtleties; their army, mostly made up of heavy infantry, took the form of a gigantic square with the mediocre assembled cavalry on the wings. They took the initiative, actually falling into the trap woven by the Punic general. The arc of a circle in fact retreated without breaking, absorbing the Roman attack. However, the phalanxes quickly moved on the wings like two vast jaws, enclosing the Romans in the trap.

The victorious Punic cavalry was at the same time in the rear of the Roman army which was annihilated. The most reliable sources speak of 45,000 Roman dead and 10,000 prisoners. The remnants of this army flowed back to Rome bringing the news of the disaster. Nearly a hundred senators had died, including the famous Paul Emile, in what remains the worst setback inflicted on Roman power. But Rome did not surrender as the codes of Hellenistic warfare predict and with Fabius Maximus, nicknamed the cunctator (timer) named dictator (magistrate bringing together all the powers for a period of six months) she fortified herself in her society, forming a a true "Sacred Union" tending its forces towards the only alternative; victory or death.

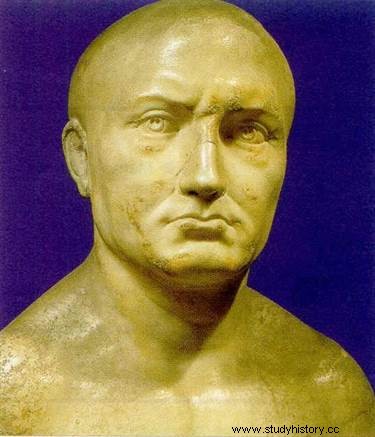

Hannibal, stuck in Italy and harassed by the Romans could not intervene when they opened a new front in Spain, on the very lands of Barcide, with at the head of the troops Publius Cornelius Scipio, the future African, the son of Publius Cornelius Scipio, defeated in the first victories of Hannibal and killed in Spain by his brothers. Scipio, newly elected consul against the laws in force (he had not completed the cursus honnorum or career of honors:a series of increasingly important magistracies, which all members of the aristocracy wishing to exercise a political role must accomplish) and had only been aedile (he still had to be quaestor and praetor before seeking the highest magistracy). But the Romans began to feel that a traditional and rigid organization would not allow them to get out of it and they agreed to many adjustments to their political system.

Hannibal, stuck in Italy and harassed by the Romans could not intervene when they opened a new front in Spain, on the very lands of Barcide, with at the head of the troops Publius Cornelius Scipio, the future African, the son of Publius Cornelius Scipio, defeated in the first victories of Hannibal and killed in Spain by his brothers. Scipio, newly elected consul against the laws in force (he had not completed the cursus honnorum or career of honors:a series of increasingly important magistracies, which all members of the aristocracy wishing to exercise a political role must accomplish) and had only been aedile (he still had to be quaestor and praetor before seeking the highest magistracy). But the Romans began to feel that a traditional and rigid organization would not allow them to get out of it and they agreed to many adjustments to their political system.

Thus the armies, made up of citizens, had to be demobilized annually to let the men return to their land or to their activity. But the realities of war prevented the authorities from allowing seasoned soldiers to disperse. Sprains will have long-term repercussions that we will see later in this short presentation. Scipio soon crushed Hannibal's brothers and landed in Carthaginian lands prompting Hannibal's recall, returning with a reduced army of veterans.

The ultimate confrontation took place in Zama in 202 BC. AD; Hannibal was about to give us a new recital of his tactical skills. He arranged his army in three lines with his Celtic and Ligurian mercenaries in the first rank, then the Carthaginian levies and finally the elite of his army, his 10,000 veterans from Italy. In front, he had placed his 80 elephants whose role was to disturb the beautiful order of the legions. Facing him, Scipio remained very academic; the Roman army ranged in its organization from the youngest employees as velites (skirmishers), to the oldest the very heavy triarii, passing respectively through the hastati and the principles.

But he had a decisive advantage; the Numidian cavalry had passed into his camp thanks to a dynastic quarrel and Hannibal had only a limited number of them. The latter launched his elephants whose attack remained sterile because the legionnaires opened their ranks and killed the pachyderms. The Roman counterattack followed and came into contact with the Carthaginian front line, which at great effort was defeated and fell back.

But he had a decisive advantage; the Numidian cavalry had passed into his camp thanks to a dynastic quarrel and Hannibal had only a limited number of them. The latter launched his elephants whose attack remained sterile because the legionnaires opened their ranks and killed the pachyderms. The Roman counterattack followed and came into contact with the Carthaginian front line, which at great effort was defeated and fell back.

Then the Romans crushed the Carthaginian levies which also came to be placed on the wings of the veterans. For such was Hannibal's plan; the tired Romans found themselves facing a gigantic line of infantry, the central part of which, the elite of the Carthaginians, was perfectly fresh, unlike the legionnaires tested by the obstinate struggle they had just fought. Hannibal seemed to prevail but it was without counting on the Numidian cavalry of the Romans who had triumphed on the wings and who now took the Punic army from behind and soon caused its collapse. Scipio, the winner, had just received a lesson in tactics that only his sense of command could reverse; he had in fact forbidden his cavalry to pursue the Carthaginians who had broken off the fight voluntarily on the orders of Hannibal with the hope of driving them away from the battlefield, the Punic thus hoping to win before his return.

Supremacy of ancient Rome in the West

Carthage no longer had any hope of victory and relied on its victor. The Romans were merciless; the Punic city had to deliver its fleet, pay a new war indemnity and lose Spain as well as part of its African territory given to the Numidians of Massinissa. Rome was entering into what is called conscious imperialism; until then, the city had been mostly defensive and struggling to loosen the noose. From now on, sure of its strength, filled with pride and strengthened in its deep organization (by the understanding between plebs and patricians), and even if demographically and materially it was devastated, Rome had in hand the elements allowing it to rebuild itself but also to lay claim to much greater dominance.

The first victim of these claims was the king of Macedonia Philip V, who had sketched a rapprochement with Hannibal and expressed his concern about the Roman victories. The limited war had already taken place alongside the Second Punic War as early as 215 BC. AD, the day after the Cannes disaster. But the Romans had other priorities and left their Aetolian allies facing Philip. But in 200 BC. J.-C., it is strong of its brilliant victory that Rome unloads in Macedonia. At Cynocephalus, Titus Quinctius Flamininus crushed the Macedonian phalanxes and proved the value of the legions. In triumph, the imperator (title of command giving authority over the troops) then proclaimed the freedom of Greece. We were indeed in a time of great fascination for Greek culture and Flamininus was a vibrant symbol of it. With Cato, a politician who became consul in 195 BC. J.-C. Rome initiates a firm reaction against this excessive penetration of "Greekism" and reaffirms its own originality.

In Eastern Affairs

Caught up in Hellenic affairs, Rome came into contact with the Seleucid Empire, the largest part of the former Empire of Alexander the Great, corresponding roughly to the ancient Persian Achaemenid Empire. The new adversary seemed considerable for Rome, but its victory of Thermopyles against Antiochos III and especially of Magnesia ended up placing Rome as arbiter of affairs throughout the Mediterranean basin. The defeated Seleucid decided to deal with the Romans, which earned him the loss of all his territories in Asia Minor up to the Taurus Mountains in the Treaty of Apamea.

Rome took advantage of this to strengthen its ally in the region; the kingdom of Pergamon. But the fate of Macedonia, though hard-hit since Cynocephalus in 197 BC. AD, was not closed; Philippe's son, Perseus, was preparing revenge after his father. He had woven, against all treaties, alliances in Greece, with the Seleucids and had reconstituted his army. Roman intervention was not long in coming, and from 172 BC. AD the Third Macedonian War began. In 168 BC. J.-C., Lucius Aemilius Paullus, better known under the name of Paul Émile crushed the armies of Perseus at Pydna and recomposed Macedonia. Rhodes having a time shown sympathy for the Macedonian is punished and loses its territory in Asia Minor and must at the same time support the elevation of Delos as a free port, ie free of taxes, which ends up draining most of the maritime traffic.

War in the West

In the East, therefore, Rome triumphed with a certain ease over the Hellenistic rulers. But on the western side, the operations turned out to be much tougher and yielded less booty. In a form of "guerrilla warfare", the Celtiberians prevented the Romans from profiting from the lands they had taken from the Barca family in Spain. In 197 BC. BC, the Romans had sent two lenders to administer the two newly annexed provinces. But it now remained to truly subjugate the territory, which was not easy. Between 154 and 152 BC. J. - C. Marcellus made countryside, but the pacification was far from being acquired and in 147 av. J.-C. Viriathus, a former shepherd, survivor of the massacre committed by the troops of the Roman lender Servius Sulpicius Galba in 150 BC. J.-C., within the framework of the pacification, became the soul of the fight against Rome.

After several successes and his stubborn resistance, he was assassinated by relatives, perhaps bribed by the Romans. Despite everything, the Celtiberians who had taken up arms again thanks to the successes of the Lusitanian chief remained on a war footing. Rome then sent its best general, the son of Paul Emile; Scipio Emilian, recently crowned with his definitive victory over Carthage during the Third Punic War which had seen the destruction of Rome's rival. Between 137 and 133 the fighting raged until the Roman managed to lock up the resistance in the solid place of Numantia which he destroyed.

New inner tensions in ancient Rome

But within its territory, Rome was rocked by several highlights. To begin with, the attempts by the Gracches brothers at agrarian reform are an important milestone in Roman history, which marks the division of the aristocracy into major political tendencies; conservatives, conservative liberals, and reformers. The small producers whose lands had been bought by the big landowners or more simply expropriated gave way to servile exploitation (the mass of slaves being considerable because of the wars). However, all these peasants without resources came to populate Rome with a population trying to survive.

But within its territory, Rome was rocked by several highlights. To begin with, the attempts by the Gracches brothers at agrarian reform are an important milestone in Roman history, which marks the division of the aristocracy into major political tendencies; conservatives, conservative liberals, and reformers. The small producers whose lands had been bought by the big landowners or more simply expropriated gave way to servile exploitation (the mass of slaves being considerable because of the wars). However, all these peasants without resources came to populate Rome with a population trying to survive.

At the same time, vast estates had been monopolized by the aristocrats on the ager publicus (public domain; land belonging to all Roman citizens) which had been entrusted to them without provided it is a definitive gift, therefore enjoyment of the property, with the State reserving ownership. The Gracches wanted to impose a redistribution of land which provoked the ire of the aristocrats and led to their assassination. At the same time, between 135 and 132 BC. J.-C. the slaves of Sicily revolt and involve a ferocious repression on behalf of the Roman authority, initiating in spite of everything a series of revolts of the same type where the Romans learned to be wary of such an influx of slaves . The most famous is undoubtedly that of Spartacus crushed by Crassus and Pompey in 71 BC. AD resulting in the crucifixion of 6,000 prisoners along the Appian Way.

Arrival of the Barbarians

Externally, the Romans gradually submitted in the 120s BC. J.-C. Transalpine Gaul (on the other side of the Alps) in order to guarantee safe access to their Spanish possessions, resulting in the creation of the province of Narbonnaise. But Rome soon finds herself faced with new and particularly serious dangers; indeed, descending from the North of Germania, the Cimbrian and Teutonic tribes begin a migration which leads them across Europe and ends up in Noricum, in the North of Italy in 113 BC. Seeing the threat, the Romans intervene but are severely beaten at the Battle of Noreia.

Continuing on their way, the Germanic barbarians arrive in Gaul make a large loop in Celtic land and enter the new province of Narbonnaise. The Romans then find their enemies in a great battle near Orange where they are once again defeated and massacred. The barbarians leave Italy and in their quest for land, cross the north of Spain and return to the Italian peninsula before separating. But in Rome, a man out of the equestrian order was made general and took over the operations; in two battles he destroyed the barbarian threat at Aquae Sextiae and then at Vercelli (102 and 101 BC).

But Rome is forever marked by the terror of the barbarians of the North, depicted in iconography and bas-reliefs as bestial, hirsute and combative beings, so much so that all part of the historiography (history of history) of the 19th century is marked by a rejection of these peoples, historians taking up literally the words of their Roman predecessors. But Rome must have had a very special history with the Germans, heterogeneous peoples whose originality never ceased to terrify and fascinate the Romans.

Nevertheless, Rome, as mistress of the Mediterranean, is called upon by a Numidian prince in the war of succession of the kingdom. At the same time, the Romans intervened militarily in what is called the Jugurtha War, named after the Berber king (therefore of Numidia) who took power and drove out his rival. The fights are tough; the Numidians served alongside the Romans as an ally in the war in Spain and therefore know Roman tactics. It was not until the appointment of Marius (106 BC), who then truly proved himself as a commander, that Rome triumphed once again and simply extended a protectorate over Numidia without annexing it. /P>

Marius' military reforms

But Marius isn't just known for his victories; he launched a major reform of the Roman army by allowing “proletarians” to participate in the war (until then, only citizens with sufficient means could serve since they had to equip themselves at their own expense). As a result, the soldiers become more attached to their leader and do not hope to return as soon as they have nothing to expect from Roman society. They also have, in these wars of conquest, a prospect of certain enrichment.

But Marius isn't just known for his victories; he launched a major reform of the Roman army by allowing “proletarians” to participate in the war (until then, only citizens with sufficient means could serve since they had to equip themselves at their own expense). As a result, the soldiers become more attached to their leader and do not hope to return as soon as they have nothing to expect from Roman society. They also have, in these wars of conquest, a prospect of certain enrichment.

Marius also decided to further reform the army by assigning each soldier a heavier pack which made it possible to reduce by as much the baggage train which cluttered the armies and slowed them down; in derision, the soldiers were nicknamed the "mules of Marius", all this in 107 BC. His action was coupled with political pretensions and the general was the first of the Grand Imperatores who put the Republic under true guardianship.

The legacy of Attalus

But before going into the details of the internal struggles of the Roman military aristocracy, it is appropriate to speak of the other military and political facts on the side of the East where Rome s gradually interferes as we have mentioned. In 113 BC. J.-C. Rome sets up in province the old kingdom of Pergame, bequeathed thanks to a will by its sovereign Attalus III. Despite everything, the transition is not obvious since the king's half-brother, Aristonicos, animates the resistance by proclaiming himself king. At the same time, Asia Minor was the seat of pirates who, by their plunder, began to worry Rome, who decided to conquer their territory and therefore created the province of Cilicia (100 BC).

We end the first part of our summary here because a long succession of armed and political conflicts tore Rome apart in the following period extending until 31 BC. AD that should be studied independently to make the substance. En tout cas, nous venons de voir l'expansion romaine au cours de plusieurs siècles qui ont fait passer la petite cité italienne au tout premier plan diplomatique méditerranéen.

A cette date Rome domine l'Italie, une bonne partie de l'Espagne, le Sud de la Gaule, une bande côtière en Illyrie (Balkans), la Grèce et la Macédoine, l'Ouest de l'Asie Mineure et l'ancien territoire africain de Carthage. Néanmoins, la cité italienne exerce son influence dans tout le bassin, règle les conflits de succession dans les royaumes voisins comme avec la Numidie; Rome assume son impérialisme et sa puissance. Elle se sent investie de la mission de soumettre le monde civilisé qui seul mérite le droit d'obéir à ses lois qu'elle considère comme étant les meilleures.

Durant les siècles précédents, Rome a fait montre de sa stabilité politique qui, malgré quelques tensions fortes, lui a permis de se sortir de situations très compromises en resserrant le corps social. Les structures de la cité sont d'ailleurs portées aux nues par dans un texte de Salluste qui explique que c'est, après que des hommes d'exception aient soutenu Rome, ses seules institutions qui lui permirent pas la suite de s'imposer aux autres. Cette vision traduit la confiance des Romains pour leur régime, la république , qui pourtant va s'étioler au rythme des guerres civiles.

Une cité en pleine gloire

Nous avons quitté Rome toute auréolée de ses victoires sur les barbares germaniques et le roi de Numidie. Ces victoires acquises au prix de grands efforts n'ont été possible qu'avec le concours d'un personnage fondamental de l'Histoire romaine; Marius. Nous avons abordé ses réformes militaires, il convient désormais d'étudier son orientation politique. Avant tout, le jeu du pouvoir à Rome se divise dès lors en deux grandes tendances qui s'affirment depuis la période des Gracches; les populares (dont faisaient partie les deux frères) qui sont partisans d'une satisfaction des attentes du peuple sur laquelle ils fondent leurs ambitions politiques en assumant surtout le tribunat de la plèbe (magistrature au poids assez considérable à Rome car ses titulaires sont inviolables et en plus bénéficient d'un droit de véto contre les décisions du Sénat), s'opposent aux optimates , ceux qui défendent l'intérêt supérieur de Rome ainsi que leurs propres prérogatives dans le jeu des pouvoirs.

L'entrée du général victorieux sur ce terrain bouleverse l'équilibre des forces; Marius s'appuie sur les populares (il était d'origine équestre, c'est à dire une dignité de l'aristocratie inférieure à celle de l'ordre sénatorial) en s'alliant avec des tribuns de la plèbe et reprend une partie de la politique des Gracches, notamment sur les réformes agraires et la gestion du sort des alliés italiens qui réclament la citoyenneté romaine de plein droit et que les réformes tronquées initiées par les Gracches ont mis dans l'embarras; en effet, Caius et Tiberius Gracchus avaient dans l'idée de reprendre des terres de l'ager publicus afin d'y installer des citoyens pauvres, mais à force d'étendre la mesure ils sont entrés en contact avec des terres de l'ager publicus occupées par des alliés et nécessaires à leur propre exploitation.

Les Gracches avaient proposé l'idée d'accorder la citoyenneté romaine à ces Italiens et ainsi élucider le problème, ce à quoi l'aristocratie avait violemment répondu par la négative. Après leur assassinat, la question est restée en suspend sans qu'une véritable réponse définitive y soit apportée. Dans le même temps, les Italiens mis en difficulté sur le sol de leur cité émigraient à Rome, diminuant de fait le contingent militaire potentiel fourni par cet allié de Rome. Les magistrats répondirent par des expulsions qui encore une fois n'apportaient pas de solution véritable. Les tensions restent vivent et l'opposition, à Rome, féroce contre toute réforme. Marius et ses partisans vont par contre s'attaquer aux anciens magistrats vaincus sur le champ de bataille, ce qui finit d'exciter les tensions. A terme Marius finit par abandonner ses alliés tribuns et se rapprocha des aristocrates qui firent assassiner les gêneurs.

La Guerre Sociale dans la Rome antique

Or l'absence de réforme finit par exaspérer les alliés qui se révoltèrent dès 91 av. J.-C. dans ce que l'on nomme la guerre sociale (de socii; alliés en latin). La guerre est rude et le retour du calme n'est possible qu'avec la concession de la citoyenneté à tous les alliés italiens, ce qui bouleverse le corps social et politique romain. En effet jusque là les réseaux clientélaires des puissants aristocrates se tissaient sur un corps d'environ 400 000 citoyens pour les contrôler et obtenir des votes favorables. Mais dès lors la masse des citoyens se chiffre en millions. De plus commence le casse-tête de l'inscription de ces nouveaux citoyens dans les tribus.

Nous avons vu qu'à Rome les citoyens sont répartis dans 35 tribus. La répartition de ces citoyens de fraiche date bouleverse la part des Romains en diminuant leur poids dans les suffrages. On propose alors de créer de nouvelles tribus ou alors de n'inscrire les citoyens récents que dans 8 ou 10 tribus déjà existantes mais en les leur réservant, ce qui aurait eu pour effet de ne pas trop bousculer l'édifice en leur donnant un impact contrôlé. Un populares tribun de la plèbe, partisan de Marius, débloqua la situation en décidant d'inscrire les nouveaux citoyens dans les 35 tribus et tint ferme par la violence. Il en profita pour nommer Marius général pour une nouvelle campagne qui s'annonçait en Orient.

La guerre contre Mithridate et la lutte entre Marius et Sylla

Du coté de la Mer Noire que l'on nommait alors Pont Euxin, un roi hellénistique brillait alors par sa puissance; Mithridate VI Eupator. Il était en concurrence avec d'autres souverains d'Asie Mineure, qui firent appel aux Romains pour les aider à vaincre ce dangereux voisin. Or Mithridate, malgré l'appui romain, fut vainqueur et occupa les royaumes alliés de Rome ainsi que la province d'Asie (le leg d'Attale). Il suscita alors un grand mouvement de révolte contre les Romains qui avaient jusque là exploité avec une grande férocité la province. En effet, l'État romain confiait à des entreprises privées la collecte des impôts; les sociétés de publicains. Ces derniers avançaient la somme calculée des impôts à l'État puis allaient se dédommager sur les provinces.

Or justement leur but était de dégager des bénéfices... et les plus importants seraient le mieux. Les populations étaient donc dans une situation de tension très forte, et l'arrivée de Mithridate sonna comme une libération. Très vite des massacres épouvantables de Romains et d'Italiens furent perpétrés (on parle de 80 000 à 150000 morts) alors que dans le même temps la Grèce et la Macédoine prenaient aussi parti pour le roi. C'est dans le cadre de cette crise que Marius devait être envoyé; c'était pour son camp une perspective d'accroissement de leur gloire et donc de leur pouvoir, sans parler du butin potentiellement récupérable.

Mais à Rome c'était le consul Sylla qui devait mener campagne dans l'ordre logique et légal des choses. C'était la première fois qu'un général se voyait démis d'un commandement sans aucun motif. Or Sylla avait déjà recruté son armée; il la rejoignit et marcha sur Rome, déclenchant immédiatement des massacres qui pour la première fois prirent une tournure légale; les proscriptions. Marius et certains de ses partisans parvinrent à fuir la répression. Sylla réorienta la politique dans l'intérêt des optimates (il était lui originaire d'une très ancienne famille aristocratique; il était patricien), puis il partit guerroyer en Orient, remportant en Grèce les premiers succès romains.

Mais à Rome c'était le consul Sylla qui devait mener campagne dans l'ordre logique et légal des choses. C'était la première fois qu'un général se voyait démis d'un commandement sans aucun motif. Or Sylla avait déjà recruté son armée; il la rejoignit et marcha sur Rome, déclenchant immédiatement des massacres qui pour la première fois prirent une tournure légale; les proscriptions. Marius et certains de ses partisans parvinrent à fuir la répression. Sylla réorienta la politique dans l'intérêt des optimates (il était lui originaire d'une très ancienne famille aristocratique; il était patricien), puis il partit guerroyer en Orient, remportant en Grèce les premiers succès romains.

Or dans le même temps, Marius ivre de vengeance, rentra à Rome et réinstaura un gouvernement suivant les intérêts populares . Les marianistes envoyèrent alors une armée combattre Mithridate directement en Asie Mineure, allant quérir les honneurs au dépend de Sylla. Mais dans sa situation de plus en plus désespérée, le roi décida de traiter avec Sylla; il devait abandonner toutes ses conquêtes et payer un tribut assez faible de 2000 talents qui montrait que Sylla avait surtout dans l'idée de liquider cette guerre afin de tourner ses armes contre ses ennemis politiques.

Les opérations commencèrent mais Sylla attira à lui l'essentiel de l'armée de son ennemi. Marius était décédé entre temps (86 av. J.-C.) et le camp marianiste dut supporter une nouvelle fois le retour en force de Sylla. Mais la résistance se fit forte dans les provinces et notamment en Espagne où Sertorius, un farouche partisan de Marius, pris les armes et fédéra les peuples espagnols pour lutter contre le parti de Sylla.

La restauration syllanienne

Sylla, vainqueur, réorganisa alors l'État romain sur un modèle qu'il pensait équilibré mais qui éludait certaines questions. La mesure la plus importante de sa restauration fut peut être de diminuer considérablement les pouvoirs des tribuns de la plèbe, organe qui jusque là avait servi les ambitions populares . Néanmoins la satisfaction des appétits des aristocrates les plus puissants ne trouvait pas de solution dans son modèle et dès sa démission, en accord complet avec sa volonté de remise sur pied de la République, l'agitation reprit, en premier lieu parmi les citoyens italiens qui avaient été contraints d'accepter dans leurs communautés l'installation de quelques 80 000 vétérans des armées syllaniennes.

La piraterie, en second lieu, créait une situation très grave en Méditerranée en faisant monter le prix du blé à Rome. Enfin, les révoltes serviles atteignaient leur paroxysme avec la révolte de Spartacus. A l'intérieur, une question ne cessait de revenir à l'ordre du jour en politique; la restauration pleine et entière du pouvoir des tribuns de la plèbe. L'édifice syllanien, à peine échafaudé, craquait de partout.

Pompée contre les pirates

Si le mécontentement était une véritable toile de fond en Italie, les problèmes extérieurs furent pris au sérieux par Rome. En effet, un jeune lieutenant de Sylla, Pompée, obtint du tribun de la plèbe de ses partisans un commandement militaire de rang consulaire s'étendant à toute la Méditerranée et jusqu'à 70 kilomètres dans les terres avec des navires et des fonds pour régler le sort des pirates. Il fut liquidé dès la fin de l'année 67 av. J.-C. soit en quelques mois. Pompée entra également en campagne contre Mithridate qui avait repris ses agissement contre les alliées de Rome, le vainquit et poursuivit son offensive jusqu'en Arménie, poussant les armes romaines plus loin que personne ne l'avait fait. Il soumit également la Syrie et descendit jusqu'à la frontière Egyptienne. La gloire qu'il venait d'accumuler sur le champ de bataille était considérable et donna lieu à dix jours de prière aux dieux pour les remercier des bienfaits accordés au peuple romain. Rome s'étendait désormais sur l'ensemble de l'Asie Mineure, la Syrie-Palestine et avait unifié la Méditerranée sous son contrôle.

Le premier triumvirat et la Guerre des Gaules

En Italie, après plusieurs défaites, les Romains, grâce à Crassus, l'homme le plus riche de Rome, se débarrassaient des encombrant esclaves révoltés. Mais Pompée vint ici aussi prendre sa part des honneurs en massacrant une partie des fuyards de l'armée défaite par Crassus. Celui-ci, affublé d'une victoire mineure, devait se contenter de l'ovatio quand son rival obtenait le triomphe. Il en nourrissait une grande amertume. C'est alors qu'une personnalité célèbrissime commença à se manifester; Caius Julius Caesar. Ambitieux, le jeune homme n'avait pas ménagé ses dépenses lors de son édilité pour offrir des jeux somptueux au peuple afin de se garantir des soutiens. Il obtint peu après le souverain pontificat ainsi qu'un commandement en Espagne où il put commencer à récolter les lauriers de la gloire.

De retour, il s'entendit avec les deux autres grandes figures de Rome de l'époque; Pompée et Crassus. Cet accord est resté dans les mémoires comme le premier triumvirat , véritable  gouvernement à trois servant, par l'association, à passer outre les verrous de la politique romaine visant à tempérer le régime et empêcher le retour de la monarchie. Cette entente mettait en contact la gloire de Pompée avec la richesse de Crassus et le génie et l'ambition de César. Cette entente lui permit d'obtenir le commandement pro-consulaire du Nord de l'Italie et des Balkans, puis du Sud de la Gaule. De là, il profita de l'agitation causée par l'intrusion des Germains parmi les Celtes pour prendre l'offensive dès 58 av. J.-C. contre Arioviste qui fut rapidement vaincu.

gouvernement à trois servant, par l'association, à passer outre les verrous de la politique romaine visant à tempérer le régime et empêcher le retour de la monarchie. Cette entente mettait en contact la gloire de Pompée avec la richesse de Crassus et le génie et l'ambition de César. Cette entente lui permit d'obtenir le commandement pro-consulaire du Nord de l'Italie et des Balkans, puis du Sud de la Gaule. De là, il profita de l'agitation causée par l'intrusion des Germains parmi les Celtes pour prendre l'offensive dès 58 av. J.-C. contre Arioviste qui fut rapidement vaincu.

La suite de sa campagne le mena à soumettre la Gaule toute entière avec l'aide dans cette tâche du fils de son collègue Crassus qui, pendant que César faisait campagne en Belgique, s'avançait en Aquitaine. Profitant de ses succès et afin de marquer les esprits à Rome, il traversa le premier la Manche et mena campagne en (Grande-) Bretagne et obtint des tributs, puis il dirigea ses troupes de l'autre coté du Rhin après avoir fait bâtir un pont de bateaux. Il en obtint notamment l'admiration de Cicéron et de bien des Romains; il avait en effet surpassé les exploits de Pompée, il venait de repousser les limites du domaine romain et de porter les aigles sur des terres encore largement inconnues. Mais le prestige que César accumulait au loin faisait croitre, à Rome, les inimitiés.

Dans la compétition effrénée pour le pouvoir, les aristocrates pouvant prétendre à entrer dans le jeu devenaient de plus en plus rares tant les exigences financières et militaires devenaient astronomiques; Pompée, César et Crassus étaient chacun bien plus puissant que les autres grands noms de Rome, même Cicéron ou encore Caton d'Utique qui lui ne pouvait se prévaloir que de sa stricte observance des règles de l'ancienne Rome. César obtint de ses collègues du triumvirat une prolongation de son commandement en Gaule, ce qui lui permit de fortifier sa conquête en abattant la dangereuse révolte de 52 av. J.-C menée par le jeune Arverne Vercingétorix.

Il en tirait une gloire et un butin immense ainsi qu'une armée de vétérans tous acquis à sa cause. C'est avec eux que Jules César entra dans une nouvelle phase de la compétition aristocratique, compétition qui devenait un duel puisqu'en 53 av. J.-C., Crassus, se sentant minoré face à la gloire de ses deux collègues, avait décidé de mener une immense expédition contre l'Empire des Parthes (actuel Iran). A la tête de sept légions, le trumvir se fit étriller par les cavaliers iraniens dans une des pire défaites de l'histoire romaine; Carrhae où il fut pris et mis à mort.

César contre le Sénat et Pompée

Déclaré finalement ennemi public, César est sommé par le Sénat de rentrer à Rome pour être jugé pour avoir mené une guerre illégale en Gaule. L'imperator n'entendait pas se soumettre si facilement tant l'ascension vers la puissance qui était la sienne avait été longue et douloureuse. Il pris donc le chemin de Rome en 50 av. J.-C., mais avec son armée. Arrivé à la frontière de sa zone de commandement, matérialisée par le Rubicon, un petit cours d'eau, il aurait prononcé la célèbre phrase, alea jacta est , littéralement « le sort en est jeté ». Il savait en effet qu'en sortant de son domaine d'exercice du pouvoir légal il entrait forcément dans une opposition militaire contre le Sénat et Pompée, avec lequel il n'avait plus de liens personnels depuis la mort de la fille de César, qui avait été donné en mariage à Pompée pour assurer son alliance.

Le Sénat, prit de cours, évacua Rome et partit avec Pompée en Orient où ce dernier savait qu'il possédait des liens clientélaires puissants auprès de rois, d'aristocrates et de vétérans pouvant rapidement lui fournir une armée pour contrer César. Mais celui-ci venait de prendre un avantage très important en mettant la main sur le coeur de l'Empire Romain, le siège du « peuple roi », le centre légal de l'ensemble romain. Il peupla le Sénat d'hommes acquis à sa cause et commença à planifier la poursuite des évènements et notamment son affrontement avec Pompée.

Le triomphe de César

L'année 48 av. J.-C. fut décisive dans l'affrontement final; le Sénat allié par les circonstances à Pompée avait donc gagné l'Orient et préparait la guerre contre un César qui avait par son initiative audacieuse pris un net ascendant sur ses ennemis. Poursuivant la dynamique de son mouvement, il se porta à la rencontre du parti pompéien. A Dyrrachium, César piétina face aux fortifications et à la supériorité numérique de Pompée. Une partie de ses troupes s'engagea imprudemment dans la place et fut taillée en pièces, ce qui provoqua sa retraite, poursuivi par son rival. Mais un mois plus tard, dans la plaine de Pharsale, César, toujours face à une supériorité numérique de ses ennemis, fit parler tout son talent, allié à la rudesse de ses vétérans des Gaules.

Sachant sa cavalerie inférieure, César avait disposé huit cohortes en couverture, qui dans l'engagement, comblèrent le vide laissé par la déroute de sa cavalerie et repoussèrent même celle de Pompée avant de prendre à revers l'armée ennemie, qui presque encerclée, rompit le combat. Pompée subit ici un échec cuisant, son armée fut détruite et il fuit vers l'Egypte, où il fut

assassiné. Pourtant César n'en avais pas encore terminé avec la guerre pour se rendre maitre du monde romain en pleine division. Fort de son succès, il suivit Pompée en Égypte où il prit Alexandrie et instaura un protectorat sur le royaume.

C'est alors que commença son idylle avec la fameuse Cléopâtre. Mais Alexandrie se révolta bientôt contre l'envahisseur étranger. Bloqué dans la ville, César parvint finalement à réaffirmer son autorité. C'est alors qu'il reçut des nouvelles alarmantes en provenance de l'Asie Mineure; Pharnace, le roi du Pont (un royaume hellénistique dont le centre de gravité est l'actuelle Crimée), héritier du fameux Mithridate, venait de pénétrer avec son armée sur le territoire romain et d'écraser le gouverneur romain.

César prit aussitôt l'offensive, traversa rapidement la Syrie-Palestine, avant de déboucher à l'Est de l'Anatolie pour rencontrer son adversaire. Le choc eut lieu à Zéla en 47 av. J.-C., et l'efficacité des troupes de César fit à nouveau ses preuves. L'ennemi fut culbuté et mis en déroute avec promptitude, arrachant à César la célèbre maxime :Vini, vidi, vici , littéralement, je suis venu, j'ai vu, j'ai vaincu. De retour à Rome, il fut fait dictateur pour un an. En 46 av. J.-C., il pris une nouvelle fois l'offensive, mais cette fois-ci en Afrique où des éléments pompéiens se préparaient à combattre. La rencontre eut lieu à Thapsus. Les éléphants éprouvèrent durement ses troupes mais César finit par les repousser et, profitant de son initiative, prit le camp ennemi et bouscula ses troupes, auxquelles il n'accorda aucune pitié ce qui est assez surprenant car il est surtout connu pour sa générosité dans la victoire.

Après cette défaite, Caton d'Utique, son ennemi mortel, se donna la mort. Le dictateur ne profita guère de son retour à Rome; en Espagne le fils de Pompée, Gnaeus faisait le siège d'Ulpia, cité fidèle à César. Il vogua donc avec célérité vers l'Espagne où il fit lever le siège et écrasa l'armée ennemie à Munda (mars 45 av. J.-C.). Revenu une nouvelle fois à Rome, il lui fut remis la dictature pour dix ans, ce qui marquait une faillite complète de la tempérance des pouvoirs républicain. César triompha pour ses nombreuses victoires et reçut une véritable cascade d'honneurs divers, jusqu'à se nomination comme dictateur à vie. Il était alors au sommet de sa gloire et de sa puissance. Les menaces militaires qui pesaient sur lui avait été écrasées. Les menaces pour la longévité de son pouvoir avaient été également dissipées puisqu'il était dictateur à vie. Il commença alors à échafauder les plans d'une immense campagne vers le royaume des Parthes, tombeau de Crassus et de ses troupes.

La conjuration et les Ides de Mars

Mais sa gloire et sa puissance commençaient à lui attirer de vives inimitiés parmi l'aristocratie qui se voyait ravalée à une maigre compétition pour des honneurs subalternes. De plus l'autorité suprême d'un seul homme était regardée de manière très négative à Rome depuis la chute de la royauté. Le système républicain avait été forgé en fonction de cette véritable phobie d'où la collégialité de la magistrature suprême; le consulat. Des soupçons très net commençaient à naitre sur une éventuelle volonté césarienne de se coiffer du diadème et de se proclamer roi.

Mais sa gloire et sa puissance commençaient à lui attirer de vives inimitiés parmi l'aristocratie qui se voyait ravalée à une maigre compétition pour des honneurs subalternes. De plus l'autorité suprême d'un seul homme était regardée de manière très négative à Rome depuis la chute de la royauté. Le système républicain avait été forgé en fonction de cette véritable phobie d'où la collégialité de la magistrature suprême; le consulat. Des soupçons très net commençaient à naitre sur une éventuelle volonté césarienne de se coiffer du diadème et de se proclamer roi.

Une conjuration fut bientôt mise sur pied et, là où les armes de Pompée et de ses successeurs s'étaient montrées inefficaces, elle finit par réussir. Le jour les Ides de mars 44 av. J.-C., César fut assassiné en plein Sénat par les conjurés et notamment son fils adoptif, Brutus. Le complot avait sans doute pour but de libérer la République du tyran, avec comme perspective illusoire de rendre la stabilité au régime et ainsi de reprendre le jeu de la compétition entre aristocrates. C'était passer sous silences les précédents créés depuis Marius et nier les dérives d'un système en crise depuis longtemps.

L'échec de la restauration républicaine

En pleine stupeur, le monde romain venait de perdre à la fois l'homme qui mettait en péril les fondements même d'un régime, et celui qui avait pourtant remporté tant de succès pour la gloire de Rome et également ramené le calme dans l'Empire. Les conjurés voulaient eux jeter son corps au Tibre et annuler tous ses décrets pour ramener l'antique libertas . Or, confrontés à l'hostilité populaire, due à politique de César en accord avec les principes populares qu'il défendait, les empêcha de mener ce projet à terme.

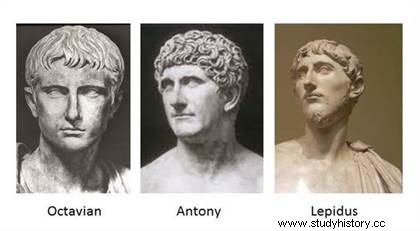

La mort du dictateur laissait néanmoins d'autres personnalités prêtes à recueillir son héritage. Le premier, Marc Antoine, son fidèle lieutenant était resté seul consul à la mort de César. Le second, Lépide, son maitre de la cavalerie, grade en second placé au coté du dictateur de manière traditionnelle pour tempérer en théorie le pouvoir personnel d'un dictateur. Le troisième, encore effacé car très jeune (19 ans) et peu versé dans les affaires militaires, Octave, petit neveu de César, mais surtout son fils adoptif. Chacun entreprit dans les mois qui suivirent, un peu timidement, de tirer leur épingle du jeu, dans l'immense vide laissé par la disparition de César.

Marc Antoine se fit remettre le testament et la fortune de César, couvrant la population de dons afin de s'en attacher l'affection. Les conjurés quant à eux, complètement isolés, quittent Rome, perdant leurs illusions. Octave avait lui appris la mort de son parent alors qu'il était à Appolonie. Il décide alors de rendre visite à ses vétérans qui le reconnaissent comme son successeur. Il s'attache les services de 3000 d'entre-eux, faisant du même coups une entrée remarquée dans la compétition.

Le second triumvirat

Mais le Sénat ne désarmait pas, et bien que les conjurés se soient retiré, mené par la personnalité de Cicéron, il déclencha la lutte contre Marc Antoine (détesté par le rhéteur); c'est la guerre de Modène, premier acte d'une longue série de guerres civiles. Antoine est vaincu et doit faire retraite vers la Provence. L'assemblée s'était entendue avec Octave, mais celui-ci, désormais propréteur (fonction qui nécessite d'avoir accompli la charge de préteur dans le cursus honorum et donc d'avoir au minimum 30 ans, donnant le commandement sur une province avec un commandement militaire, l'imperium réduit par rapport à celui du consul et du proconsul) et, possédant ainsi l'imperium , marche à la tête de huit légions sur Rome.

Il s'empara alors du trésor de l'État qu'il distribua à ses troupes. Il se fit aussitôt nommer consul. La réaction sénatoriale fit long feu; en dépit de ses engagements, Octave se réconcilia avec Antoine par l'entremise de Lépide. Ils fondèrent alors tous les trois le second triumvirat, qui contrairement au premier, était une entente légale, sanctionnée par un texte législatif. Les effets furent immédiats; une proscription fut lancée dans laquelle périt Cicéron, entre autre, parmi les probables 300 victimes (150 sénateurs et 150 chevaliers). Les triumvirs se partagèrent également le monde romain :Lépide reçut la Gaule Narbonnaise et les provinces ibériques avec trois légions, Antoine, le reste de la Gaule, ainsi que la Cisalpine (Nord de l'Italie) avec 20 légions et Octave, L'Afrique, la Sicile et la Sardaigne avec 20 autres légions.

Il s'empara alors du trésor de l'État qu'il distribua à ses troupes. Il se fit aussitôt nommer consul. La réaction sénatoriale fit long feu; en dépit de ses engagements, Octave se réconcilia avec Antoine par l'entremise de Lépide. Ils fondèrent alors tous les trois le second triumvirat, qui contrairement au premier, était une entente légale, sanctionnée par un texte législatif. Les effets furent immédiats; une proscription fut lancée dans laquelle périt Cicéron, entre autre, parmi les probables 300 victimes (150 sénateurs et 150 chevaliers). Les triumvirs se partagèrent également le monde romain :Lépide reçut la Gaule Narbonnaise et les provinces ibériques avec trois légions, Antoine, le reste de la Gaule, ainsi que la Cisalpine (Nord de l'Italie) avec 20 légions et Octave, L'Afrique, la Sicile et la Sardaigne avec 20 autres légions.

Il leur restait maintenant à venger César de qui ils revendiquait tous l'héritage. De concert, Antoine et Octave se mirent en marche vers l'Orient. En 42 av. J.-C., ils rencontrèrent l'armée des conjurés Cassius et Brutus à Philippes. L'affrontement se déroula en deux temps; le premier jour, Antoine, contournant le dispositif ennemi par le Sud fut contraint à un choc frontal indécis avec les unités de Cassius alors que dans le même temps, à l'Ouest, le camp d'Octave fut pillé par les troupes de Brutus. Cassius, voyant ses troupes flancher et ne voyant pas le succès de Brutus se suicide. Le lendemain les triumvirs continuèrent à prendre l'initiative; Octave rejoignit Antoine sur ses positions et Brutus se porta à la rencontre des unités de Cassius, face à Antoine. Le combat s'engagea et vit, après une âpre lutte, les troupes césariennes l'emporter. Brutus, abandonné par ses troupes se suicida à son tour.

L'Orient tomba alors en grande partie aux mains des triumvirs ce qui provoqua un nouveau partage du monde romain; Lépide dut se contenter de la seule Afrique alors qu'Antoine recevait la totalité de la Gaule et Octave l'Espagne à laquelle il ajouta ses possessions. La répartition des tâches allait de paire; Antoine devait ainsi partir vers l'Orient réaliser le projet de César de conquête de l'espace parthe, plein de gloire et de richesse, marchant ainsi dans les traces d'Alexandre le Grand. Octave recevait la rude mission de régler le sort de Sextus Pompée, fils du grand général qui occupait la Sicile ainsi que de lotir les vétérans de la campagne de Philippes de terres. Lépide était écarté très nettement de la politique.

Octave et Antoine, entre tension et réconciliation

Le don de terres fut un véritable casse-tête pour Octave qui entre d'ailleurs en conflit avec les partisans d'Antoine ce qui manqua de peu de déclencher les hostilités entre les deux hommes. Mais cela accompli, et assuré du soutient de son collègue après l'entrevue de Brindes, Octave attaqua puissamment la Sicile et se rendit maitre incontesté de l'Occident. Dans le même temps, Antoine apparaissait comme l'homme fort en Orient. Il séjourna à Alexandrie, et comme César avant lui, fut séduit par Cléopâtre, point de départ d'une légende magnifique mainte fois portée à l'écran et ayant fait couler des hectolitres d'encre.

Mais Antoine n'oubliait pas sa mission principale. Il marcha ainsi contre les Parthes mais sans être défait lui même, il fut dans l'incapacité de remporter un quelconque succès. Rentré à Alexandrie il y célébra pourtant son triomphe, ce qui scandalisa les Romains car seule Rome pouvait voir l'accomplissement de ce rituel sacré. Les rumeurs sur les déviances d'Antoine commencent alors à se multiplier à Rome, savamment entretenues par Octave. En effet les Romains concevaient le monde et ses habitants selon tout un ensemble de présupposés; les Gaulois étaient ainsi considérés comme de bons combattants manquant singulièrement de réflexion, les Grecs étaient décrits comme calculateurs, fourbes et efféminés... Globalement, les Orientaux apparaissaient comme mous et lascifs, à l'opposé des vertus cardinales romaines, la sobriété, la tempérance, la maitrise de ses passions. Jouant donc sur les sentiments xénophobes de ses compatriotes, Octave orchestra la suspicion contre son rival, jusque là populaire.

La rupture et les débuts de l'Empire

En 32 av. J.-C., il est pourtant mis en difficulté à Rome. Le triumvirat remis en question le laisse sans pouvoir de commandement et l'amène prudemment à quitter Rome où ses ennemis commencent à s'agiter. Mais il força alors la décision. Ayant rejoint ses troupes il rentra à Rome par la force, convoqua le Sénat et fit déclarer par senatus consulte la guerre à Antoine et Cléopâtre.

En 32 av. J.-C., il est pourtant mis en difficulté à Rome. Le triumvirat remis en question le laisse sans pouvoir de commandement et l'amène prudemment à quitter Rome où ses ennemis commencent à s'agiter. Mais il força alors la décision. Ayant rejoint ses troupes il rentra à Rome par la force, convoqua le Sénat et fit déclarer par senatus consulte la guerre à Antoine et Cléopâtre.

Dans le même temps, Antoine préparait lui aussi l'affrontement. Réalisant une politique semblable à celle de son rival, il alimentait une intense propagande en même temps qu'un renforcement de ses armées. Le monde romain, en tension extrême autour de deux pôles rivaux s'apprêtait à se déchirer une nouvelle fois dans un déchainement de violence. Octave fut nommé consul pour l'année 31 av. J.-C., et après avoir reçu un serment de fidélité par tout l'Occident, il prit l'offensive qui le mena de l'autre coté de la mer Adriatique.

Le choc eut lieu à Actium où le fidèle général d'Octave, Agrippa, écrasa la flotte orientale, remportant un succès décisif. Les deux amants romantiques, en déroute, rentrèrent en Égypte où ils se suicidèrent, laissant à la postérité une apothéose dramatique largement exploitée. Rome n'avait plus qu'un seul maitre comme en 44 av. J.-C., mais cette fois l'opposition toute entière était décapitée, tant militaire que politique (par les proscriptions). Octave est pourtant face à une tâche encore gigantesque et que son père adoptif n'avait pu mener à son terme; réformer complètement la République pour lui rendre sa stabilité tout en préservant son pouvoir sans que cela ne provoque l'indignation générale... Le temps de l'Empire romain est venu.

Bibliographie de la rome antique

- Histoire de la Rome antique, de Lucien Jerphagnon. Pluriel, 2010.

- Jean-Michel David, La république romaine, De la deuxième guerre punique à la bataille d'Actium, 218-31 av. J.-C., Seuil, 2000.

- Marcel Le Glay, Yann Le Bohec, Jean-Louis Voisin, Histoire romaine, PUF, 2006