In 1809, although fighting continued on the Peninsula , it seemed that the French dominion on the continent was unchallenged. However, in early April hostilities resumed between Austria and France in what would become known as the War of the Fifth Coalition . The Austrians invaded Bavaria and seemed to have the initiative. However, Napoleon managed to stop them at Eckmühl. The tables had been turned and now it was Napoleon who was invading Austria trying unsuccessfully to cross the Danube at Aspern-Essling .

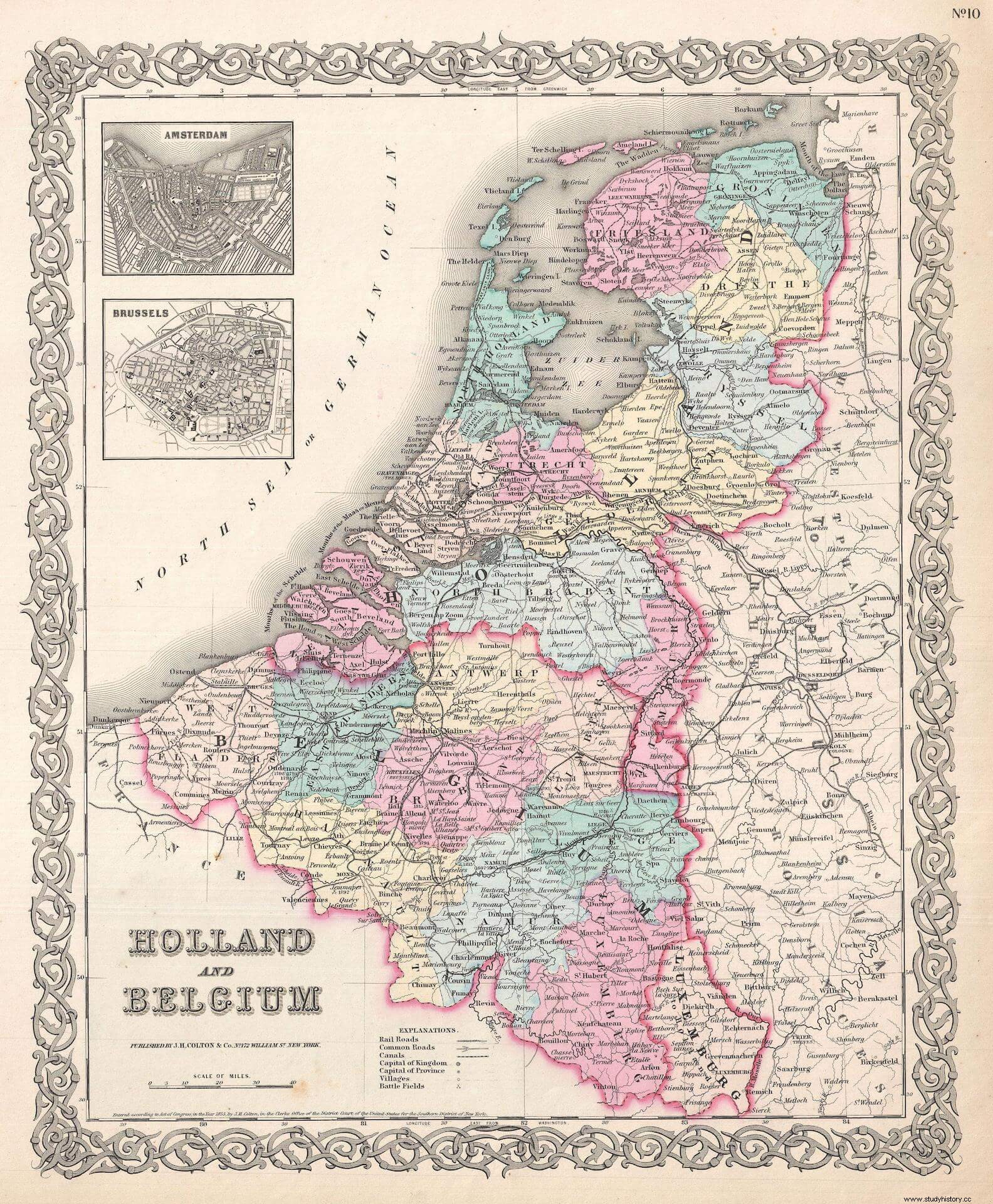

With the entire bulk of the French army facing the Austrians, the English saw an opportunity to set foot on the continent again. In April, Wellington commanded 23,000 British in Portugal. But the main effort was going to hit another point much closer. From June 1808 an attack on the ports of the Scheldt was planned and to eliminate the threat that Napoleon himself described as "a loaded pistol pointed at the head of England". In July 1809 an expeditionary force was set up of 42,000 men with the mission of landing on the island of Walcheren and once there destroy the ships, arsenals and shipyards of the cities of Vlissingen and Antwerp. The contingent was placed under the command of Lord Chatham, older brother of William Pitt the Younger (famous Prime Minister who had died in 1806). The naval forces, made up of 264 warships of all types and more than 350 transports, were under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Richard Strachan and were ordered to cooperate with the ground forces in the destruction of French installations, as well as to carry out a blockade of the Scheldt.

Lord Chatham's choice seems to have been a poor one. He was known as "the late earl" for his habit of getting out of bed as late as possible. Fittingly enough, he had two pet turtles that always accompanied him everywhere. The choice of Sir Richard Strachan was also not very successful, since he only seemed to care about the state of his ships and ignored orders to cooperate with ground forces, essential in any amphibious operation.

The campaign began on July 16 when the first troops landed unopposed on the islands of Walcheren and Beveland . Everything seemed to be going according to plan. William Keep, a soldier of the 77th Regiment wrote to his house the following:

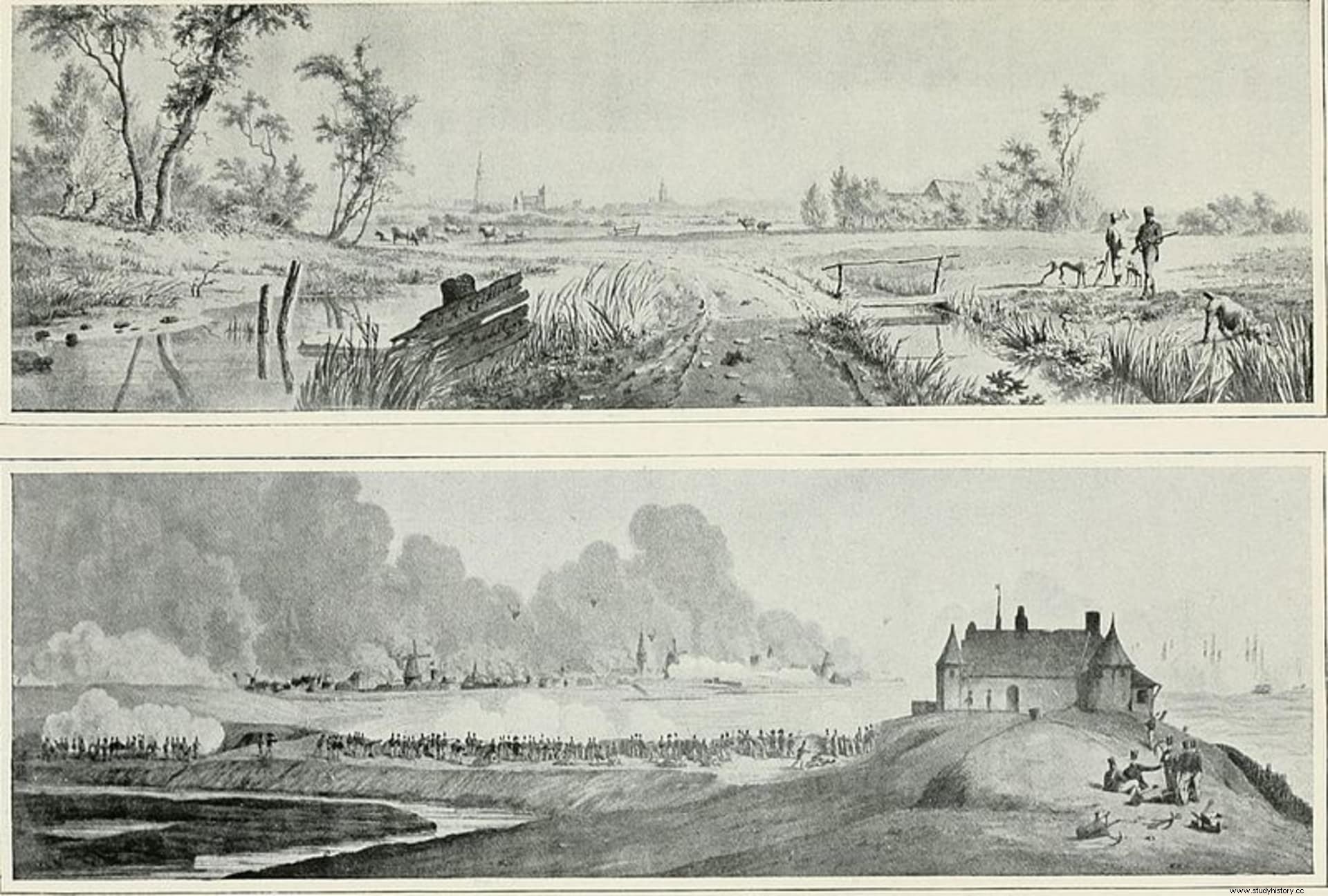

The English took it easy and on July 30 they took the small town of Middelburg in the east of the island. Then, on August 1, the city of Vlissingen, one of the initial objectives, was surrounded. At this point the French began to react. There were some 9,000 troops in the area under the command of General Louis Monnett. His morale and discipline were not very high, but Monnett tried to make the most of them. On the 9th, he ordered the dam gates to be opened to flood the land and thus hinder the British advance. The weather was allied with the Gauls as it began to rain profusely. The flood did not save Vlissingen but it had consequences much later. On the 13th the bombardment began both from land and from the sea. The next day, talks began for the capitulation of the punished city, which took place on August 16. At that time, a British casualty list reports that there were 117 dead, 586 wounded and 44 missing. The expedition seemed to go smoothly.

But it was all a mere illusion. Before the first of the landings had begun, Napoleon had already taken notice of the Austrians at the battle of Wagram , so the opportunity to destabilize the French rear had been lost. But unlike the leisurely British pace, the Corsican acted with his customary speed. Upon receiving news of the landing he ordered various units to begin massing in the vicinity of Zeeland province and commissioned Bernadotte to take command of them as soon as possible. August 15 Bernadotte he arrived in Antwerp with 20,000 troops, definitively nullifying the chances of a British victory. On August 25, Lord Chatham held a council of war in which, after assessing the situation, it was decided to abandon any offensive operation, limiting himself to blockading the Scheldt. In his report sent to London he noted that 3,000 men were sick. The disaster had just begun.

Epidemic in Walcheren

The first cases of what was to be known as “Walcheren fever ” were declared on August 19 among the troops stationed on Beveland Island, but before long it had spread to the entire expeditionary force. The flooding of the island had caused the sanitary conditions of the British troops deteriorated rapidly. John Webb, the Inspector General of Hospitals, wrote the following:

Those affected manifested a picture of fever, weakness, swollen and white tongue, lack of appetite, headache and pain in the extremities and swelling of the spleen. Many of the sick began to die. The first evacuations of patients were organized immediately, but their number continued to increase. On September 17 there were more than 8,000 men hospitalized and in October, the percentage of patients exceeded the number of men fit for service (58% compared to 42%). Although Walcheren fever was once thought to be some type of malaria, it is now thought to be a combination of various diseases, mainly exanthematic typhus – a disease transmitted by lice – and typhoid and paratyphoid fevers – a disease transmitted by water and food contaminated with fecal matter–.

The medical body took action on the matter as soon as the epidemic aspect of the disease became evident. Buildings were refurbished to allow the sick to remain dry and away from "toxic miasmas." Drinking water was also transported from Great Britain. Unfortunately, the patients were treated according to the medical philosophy of the time. Those affected had to cleanse their bodies of toxins and for this they were subjected to bleeding, sweating and vomiting were induced. Likewise, they were supplied with various tonics such as hot wine, saltpeter dissolved in malt or infusions with quinine bark. It is very likely that these sanitary measures did more harm than good . One officer noted that the number of deaths was so high that only one corporal and eight men were assigned to each funeral, a ceremony that was held at night and without torches to avoid demoralizing the troops.

Walcheren fever also affected medical staff. As of mid-October, 23 of the 54 medical officers were sick. Even John Webb fell ill on September 13 and had to be evacuated to Britain. He was one of the 12,863 men who were evacuated between August 21 and December 16. The avalanche of patients was such that it exceeded the capacities of the English hospitals, so many of them remained in the ports or on the beaches waiting to be treated. The one who didn't get sick was Lord Chatham. On September 9 he left the command to his second of his and left for England.

The expedition officially ended in February 1810 with the evacuation of the last troops. 60 officers and 3,900 men had perished. 40% of the expeditionary force it had been affected and six months later some 11,000 men were still convalescing. Many of them were permanently disabled and those who recovered and were sent to fight in the Iberian Peninsula were found to fall ill more frequently than other soldiers. An unmitigated disaster.

Bibliography

- «The Expedition to the Scheldt, Walcheren, 1809«. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps (1923) Vol. 40, pp:215-220.

- Martin R. Howard (1999):«Walcheren 1809:a medical catastrophe«. British Medical Journal. Vol 319, pp:1642-1645.

- John Lynch (2009):«The lessons of Walcheren Fever, 1809«. Military Medicine . Vol 174, pp:315-319.

- Penelope Hunting (2009):«Walcheren 1809 «. Journal of Medical Biography . Vol 17. p 209.