At the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, Felipe V he had had to give up his Italian possessions (Sardinia, Sicily, Naples, Milan and the Presidios of Tuscany) as part of the price to be recognized as king of Spain and the Indies. However, he never resigned himself to the loss of it and aspired to recover them as soon as he had the chance (see Desperta Ferro Modern History #39: Felipe V against Europe ). In 1717, considering the international situation propitious, he took the first step by seizing the island of Sardinia from Austria, which, immersed in one of its frequent wars with the Ottoman Empire, could do little to avoid it.

Emboldened, in 1718 he upped the ante by sending an expedition against Sicily, newly incorporated into the kingdom of Savoy. During the month of July the Spanish occupied most of the island, cornering the Savoyards in some strongholds. Great Britain and France were quick to react, signing an agreement to maintain the status quo prevailing. The accession of Austria and the Netherlands made it the Quadruple Alliance. The coalitionists demanded that Felipe V return his conquests. In return, the children he had had with Isabel de Farnesio, his second wife, would receive the dukedoms of Tuscany and Parma and Placencia.

Meanwhile, Great Britain had sent a powerful squadron to the Mediterranean to reassert her position. On August 11, without prior declaration of war, he attacked and defeated the Spanish, much inferior in number and quality, in front of Cape Passaro . Then, taking advantage of his command of the sea, he moved an Austrian contingent to Sicily to dispute control of the island with the isolated Spanish expeditionary force. Neither the diplomatic setback nor the military defeat persuaded Philip V of the need to enter into negotiations. With no choice but to use force, Britain declared war on Spain on December 29 and France on January 9 of the following year.

In the campaign of 1719 Spain made the first move. On March 7, a fleet with 5,000 men on board sailed from Cádiz to Great Britain, the embryo of an army with which James Stuart intended to seize the British crown from George I (see «Scotland, 1719. The last Great Armada» in Awake Ferro Modern History #38). A terrible storm dispersed it to the west of Fisterra, forcing the battered ships to take refuge in the first port they could reach. France set out in mid-May, concentrating a large army in Irun. On June 17 he obtained the capitulation of Hondarribia and on August 19 of San Sebastián. The small army that the Spanish managed to muster remained powerless in Pamplona. Unable to oppose the enemy's designs, he just kept a close eye on him.

The British counterattack

It was around this time that the idea of sending an expedition to the northern coast of Spain to cooperate with the French was hatched. The proposal came from Lord Stair, the British ambassador in Paris, and was enthusiastically welcomed by James Craggs, Secretary of State for the Southern Department (the senior Foreign Minister of the two in the cabinet, responsible for relations with the Catholic and Muslim states of Europe) and one of the most prominent members of the Regency Council established in London in the absence of George I, who was in his native Hanover. The monarch was suspicious of the operation. With only twelve thousand soldiers spread between Britain and Ireland, he feared that his kingdom might be left defenseless. To obtain his acquiescence, the regents had to promise him that they would keep until the return of the expedition the Dutch troops that they had hired at the beginning of hostilities.

For the operation, some five thousand soldiers were distributed into ten battalions of infantry, with fifty horses and a powerful siege artillery train, commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Richard Temple, Viscount Cobham, a veteran of the War of Succession, like most of his senior officers. Vice Admiral James Mighells's squadron, with three ships, a frigate, two bombards and two fireships, would lend them support. Slow preparations and unfavorable weather delayed the departure until early October. By then military operations were centered in Catalonia, with the French besieging Seo de Urgel and preparing to attack Rosas. Without the possibility of cooperating with them, it was necessary to find an alternative objective of sufficient importance. A Coruña, the most important stronghold of the Kingdom of Galicia, was chosen.

Cobham was scheduled to be in Galician waters with Rear Admiral Robert Johnson's squadron. With two ships and a frigate, Johnson had been operating in the Bay of Biscay for some time. In June he had participated in the destruction of the Santoña shipyard and at the end of September he had attacked Ribadeo. However, by the time Cobham arrived at the scheduled rendezvous, Johnson, who had been waiting for more than a month, was on his way back to England with supplies and water running low. Without the help of Johnson Cobham he did not feel capable of forcing his entry into the bay of A Coruña. On October 8 he set sail for Vigo in search of more affordable prey, leaving a trail of devastated villages in his wake.

The attack on Vigo

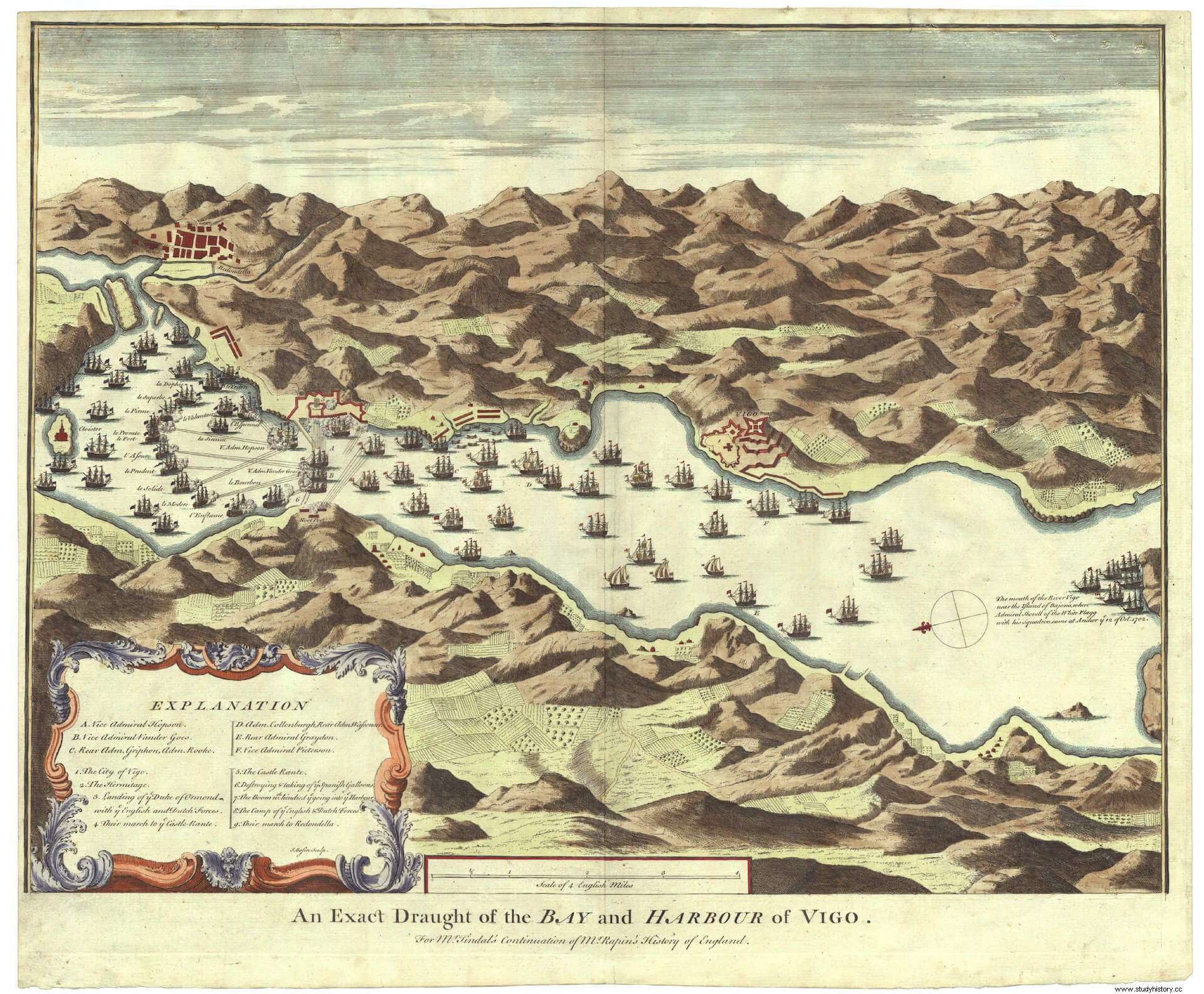

Vigo was defended by the Laxe battery, a bastioned wall with the San Sebastián fort attached to the highest part of the enclosure and, dominating the whole complex from an almost inaccessible terrain , the castle of the Castro. Although the fortifications were not in good condition, the most pressing problem for the governor of Tui province, Lieutenant General D. Tomás de los Cobos, Marquis of Parga, was the scarcity of defenders. In his entire jurisdiction there were barely five hundred regular soldiers, the rest were militiamen who, although willing, could do little against a well-disciplined and trained enemy.

The invading fleet began to anchor at the entrance to the Vigo estuary on the morning of October 10. During the day the English landed without opposition. Observing the disparity of forces, Parga had decided to leave Vigo and concentrate on the Castro. It was defended by ten companies of the Spanish Infantry Regiment, "which with the officers did not reach four hundred men," and another four hundred armed civilians with their own commanders. Command was held by the Governor of Vigo, Brigadier José de los Herreros, "a man of great judgment, intelligence, honor and experience, which he had acquired in many years of the Flanders school."

Vigo surrendered on the 12th and despite the pleas of the municipal authorities, it was unceremoniously looted. Cobham then concentrated on conquering the castle. To save himself from an assault that promised to be bloody, he decided to bomb it. On October 13, he placed a large battery of thirty-four mortars under the protection of the San Sebastián fort with pieces of "all calibers, from eighteen to twenty arroba pounds, two arrobas, up to three arrobas", which were they added more than a dozen small Coehorn "hand mortars." Two days later he installed another battery with two large mortars at the Gamboa bastion (at the southwestern end of the wall).

As soon as the pieces were ready, the bombardment began, occasionally joined by the bombards, anchored a short distance from the coast. A lethal routine was quickly established:from dawn to noon and from dusk to early morning, shells rained down on the fortress without the defenders being able to do much to evade their devastating effects:

The casualties increased with each passing day. Herreros himself was hit in the left arm by a bomb shell while he was encouraging his men, dying shortly after. On the 17th, after the customary morning bombardment, the defenders were ordered to surrender. The reformed Colonel Fadrique González de Soto, temporarily in command, replied that he could not hand over the castle «because he had a large garrison, officers of great honor, a lot of gunpowder, bullets and food; and, above all, because there would be no gap.” However, after holding a court martial, he decided to report the situation inside the fortress by letter to D. Guillaume de Melun, Marquis of Risbourg, who had traveled from A Coruña to O Porriño to closely follow events. Risbourg, an experienced soldier who held the position of captain general and viceroy of Galicia since 1707, authorized him to act as he saw fit.

With his honor safe, González de Soto chose to capitulate the following day. Cobham was generous to the vanquished, allowing regular troops to go out "with their weapons and baggage, to the sound of boxes and with unfurled flags." The militiamen, unarmed, would be free to go where they wanted. On October 21, the survivors of the garrison formally left the Castro. The violence of the bombardment had cost the defenders 66 dead and 164 wounded according to Spanish sources. The British counted over three hundred killed or wounded, admitting to having lost "only two officers and three or four men killed."

During the siege, the invaders tried to exploit local resources to subsist, demanding provisions and contributions "under penalty of military execution", that is, reprisals. To prevent this, Risbourg demanded a great sacrifice from the civilian population:he ordered the residents to “remove their fruits and cattle inland and abandon their houses; which was executed with such resignation and obedience that there were countrymen who threw their grains into the rivers and broke the wine pipes, so that the enemies would not seize them.»

The English detachments, forced to move further and further from their camp, suffered a steady trickle of casualties. Every day "civilians and volunteers brought some prisoners and deserters, killing some enemies." The viceroy boasted of having taken "up to three hundred men from the enemies" in these operations typical of the war of parties in which the militiamen, with their exhaustive knowledge of the terrain, proved to be in their element. Frustrated, the British didn't pull any punches:

Owner of Vigo and its surroundings, Cobham decided to expand the radius of his operations by attacking Pontevedra. On October 25, a thousand men under the command of Field Marshal George Wade landed at the Ulló cove. From there they marched overland to Pontevedra without encountering resistance. Risbourg, fearing that Santiago might be the final target of the English, had ordered Parga to withdraw to Caldas "and if they followed him, to Padrón, where he would cut the bridge [over the Ulla] and fortify himself." However, the British did not intend to go further. They remained in Pontevedra until November 4 and before leaving, they burned several private houses and public buildings, as they had done before in Redondela and Marín.

Everyone loses

By then Cobham had decided to call off the operation. Alleging "the scarcity of food, which he suffered from," he re-embarked his army and set sail on November 7. The operation left Britain with a bittersweet aftertaste. Although the vulnerability of the Spanish coast had been made clear, neither Vigo was of sufficient importance as a prestigious objective, nor was the meager booty obtained –seven merchant ships, a hundred mostly disabled artillery pieces, more than two thousand barrels of gunpowder and some eight thousand muskets – offset the cost of the operation.

All the same, Philip V had had enough. The campaign of 1719 had made clear the international isolation and defenselessness of his kingdom. On January 26 of the following year, he grudgingly agreed to the Quadruple Alliance claims, stating that he was "sacrificing his interests to the repose of Europe." The war was over and new events would soon consign it to oblivion in the main European chancelleries. In other places it was not so easy to turn the page, as Commander William Dalrymple would confirm when he passed through Vigo half a century later:

As on too many occasions throughout history, it was the subjects who paid for the foolish obstinacy of their king.

Bibliography

Álvarez Blázquez, J.M. (1960). The city and the days. Historical calendar of Vigo . Vigo:Ed. Monterrey.

Black, Jeremy (2017). Combined Operations. A global history of Amphibious and Airborne Warfare. Lanham, MD:Rowman &Littlefield.

Bouza Brey, Fermín (1945). Diary of the siege of the Castro de Vigo by the English in 1719. Cuadernos de Estudios Gallegos , Vol. III, 471-474.

Boyer, A. (1719). The Political State of Great-Britain, vol. XVIII. London:A. Boyer.

Clowes, Laird (1898). The Royal Navy. A History from the Earlier Times to the Present, vol. III London:Sampson Low, Marston and Company, Ltd.

Dalrymple, William (1777). Travels through Spain and Portugal, in 1774; with a short account of the Spanish expedition against Algiers, in 1775. London:J. Almond.

Dalton, Charles (1910). George the First´s Army 1714-1727, vol. I. London:Eyre and Spottiswoode, Ltd.

——- (1912). George the First´s Army 1714-1727, vol. II. London:Eyre and Spottiswoode, Ltd.

Meijide Pardo, Antonio (1970). The English invasion of Galicia in 1719. Santiago de Compostela:P. Sarmiento Institute of Galician Studies.

Michael, Wolfgang (1939). England under George I. The Quadruple Alliance. London:McMillan and Co.

Ozanam, Didier (1987). Philip V, Isabel Farnese and Mediterranean revisionism (1715-1746). In History of Spain by Ramón Menéndez Pidal , vol. XXIX, volume I. Madrid:Espasa-Calpe.

Santiago y Gómez, José de (1896):History of Vigo and its region . Madrid:Printing. and Lithogr. of the Asylum for Orphans of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Villegas y Piñateli, Manuel de (1724). List of the site of the port of Vigo carried out by the English, in the year 1719. Retrieved from http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000100363