Hanoi sent an entire division through the Ho Chi Minh Trail to reinforce Viet Cong (VC) forces near Saigon and ordered the battle-hardened VC 1st Regiment to mount an attack on the new US Marine Corps (USMC) airbase at Chu Lai. They thought the Americans would give up if they were shown up front that it was going to be a long and bloody war.

The Americans knew the 1st Regt. VC. Their commander, Le Huu Tru , had led his unit against the French in the iconic battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954. More recently, he had made a big splash after overwhelming several units of the South Vietnamese Army near the town of Ba Gia, from which point its veterans liked to refer to themselves as the "Ba Gia Regiment."

For several weeks in the summer of 1965 the Marines were following rumors and their agents reported that 1st Regiment. VC was planning to attack the Chu Lai base, but the most complete available reports placed the enemy headquarters in the mountains, 50-60 km to the west. However, luck changed. On August 15, a National Security Agency analyst in Saigon tasked with studying radio direction-finding reports found several that placed the enemy on the Vân Tuóng peninsula, a day's night march from Chu Lai. The information was quickly passed up the chain of command, and the next day Lt. Gen. Lewis Walt, head of the Marine Corps in Vietnam, flew to Saigon to receive the intelligence report. He immediately returned to his headquarters in Da Nang and gave orders to prepare a pre-emptive strike.

The Americans needed to hide from the enemy that they had radiogoniometric means to locate the position of their forces, so they prepared an alibi that was pure invention:the information about the whereabouts of the 1. er Reg. It would have been supplied by VC by a septuagenarian deserter who would have gone to the South Vietnamese on August 15.

The General Walt , a multi-decorated officer from World War II to Korea, was quick to react. Instead of waiting, he decided to take the initiative and anticipate a potential attack on Chu Lai, appointing Colonel Oscar F. Peatross as joint commander and designating two Marine battalions, the 3rd Marine Regiment's 3rd and the 2nd of the 4th Regiment, as assault units. A third unit, the 3rd Battalion, 7th Regiment, was assigned as a reserve, remaining embarked in the Philippines. The ships were ordered to set sail immediately for Vietnam.

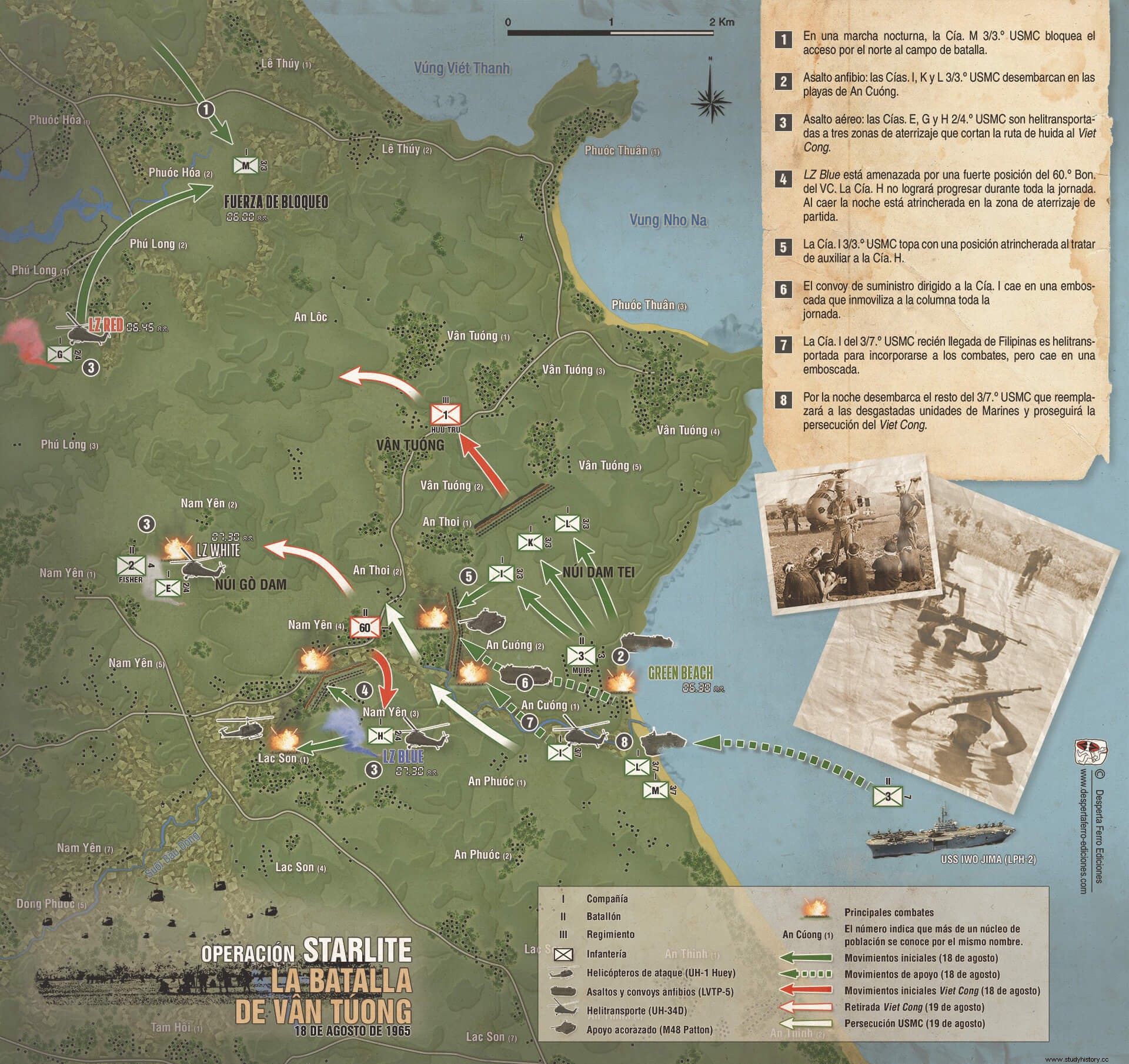

The Marines quickly opted for a combined air and amphibious assault, a classic “hammer and anvil” operation that had been tried for nearly a decade but had never been tested in combat . The 2/4th USMC would be helicoptered to three landing zones, Landing Zone Red, LZ White, and LZ Blue, to serve as an "anvil" in the interior, away from the coast. The 3/3rd USMC would act as a "hammer", landing on the beach in the early morning, from which they would destroy the enemies in their path and push the rest into the arms of the anvil.

The enemy was not entirely unaware of the possibility of an attack by the Marines, but they were unaware of their ability. They were aware that the Americans did not have enough helicopters to quickly move a decisive fighting force onto the battlefield, and so they deduced that the Marines would have to approach by land, in which case they would have plenty of time to consider their concerns. options and fight or retreat to the mountains to the west as the situation dictated. What they did not have was the amphibious and helicopter capabilities to mount a combined air and sea assault. They also didn't take into account how quick the Marines were to make decisions and maneuver.

Speed and stealth defined the situation. The units had to be organized, the helicopters and ships distributed, and the orders transmitted; the Marines had less than two full days to accomplish it. The operation was to be called Satellite, but the electrical generator in the bunker where the operators were working failed, misinterpreting the instructions while typing in the dark, and the operation went down in history as Operation Starlite.

Operation Starlite begins

As the sun rose on the morning of August 18, 1965, the inhabitants of An Cuóng, the small village near the coast on the Vân Tuóng peninsula, were stunned seeing a United States Navy fleet anchored off the coast. In the blink of an eye, the messengers spread the word and, before the eyes of the Vietnamese, the ships began to unload the landing craft that lined up for the assault after dismissing it, preparing it with naval and aerial fire from the beach to the have a civilian population in the area.

The news spread quickly among the units of the 1st Regiment. VC. While some of them prepared for combat, the regimental headquarters prepared to fall back to the west. To provide cover for them, Captain Duong Hong Minh moved ashore to set up guided-detonation antipersonnel mines where he believed the Marines would land. They were to inflict as many casualties as possible and give them breathing space.

Lieutenant Phan Tan Huan's unit supported them, with an important and risky mission:they were less than 4 km between the landing beach and the headquarters of the 1st Regiment. VC in the village of Van Tuong. Huan organized a small contingent of reliable troops who fanned out on a small ridge midway between the coast and HQ to delay the Marines and allow HQ elements to withdraw.

The LVTP-5 amphibious vehicles reached the shore and the 3/3rd USMC, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Muir, began the assault. It seems that Captain Minh suffered an anxiety attack and prematurely activated the anti-personnel mines; Although he claimed that he had eliminated 15 marines, in reality the detonation produced no casualties.

As the 3/3rd USMC landed, Lt. Col. Joseph “Bull” Fisher's 2/4th USMC landed – company after company – on the three designated landing zones:from north to south, LZ Red, LZ White, and LZ Blue. G Company landed without incident at LZ Red and began moving out to sea. Company E and Lieutenant Colonel Fisher's command group were next. They reached LZ White under light mortar and small arms fire, but drove the enemy east. Company H, led by Lt. Homer K. “Mike” Jenkins, was not so lucky landing at LZ Blue, a clearing where they were easy prey for rifle fire from Commander's VC 60th Battalion headquarters positions. Tranh Ngoc Trung. The Marines came under fire even before the helicopters landed, and had barely descended from their helicopters when Marine First Class Jimmy Brooks was fatally shot. Until this point in the war, the Viet Cong she had never held his ground in the face of a Marine attack, and Lieutenant Jenkins had no reason to think it would be any different now. His orders required him to take two objectives and he decided to attack both simultaneously:one was near elevation 43, the other was the village of Nam Yên 3. Jenkins sent one platoon against each objective and left one in reserve. Neither attack was successful. In Operation Starlite, the Marines experienced for the first time what it was like to fight professionalized troops like those of the 1st Regiment. VC. They discovered that many of the cabins were actually bunkers; as its side faces fell, fortified positions with a well-defined field of fire appeared, and devastating machine gun and small arms fire halted their attack.

Lieutenant Jenkins withdrew his men and opted for take the objectives consecutively and elevation 43 would be the first, which would allow dominating the surrounding terrain. While he was getting ready, he was joined by two tanks that had just landed on the coast and the attack of Army helicopter gunships. With this support it didn't take much fighting to capture the hill and he immediately prepared to assault Nam Yên 3 village again.

Meanwhile, the 3/3rd USMC was having trouble. Lieutenant Phan Tan Huan's retarding action had an effect. His intense fire slowed and momentarily halted the Marines' advance. Ensign Burt Hinson of Company K reorganized a platoon, attacked, outflanked the blocking contingent, and resumed the advance, but the brief delay was enough for elements of enemy headquarters to escape to the west. The Marines did not learn until long after the battle that the 1st Regt. The VC had been directly in their path and had they broken through Huan's blocking force sooner they would have been able to capture or eliminate the regiment's commanders.

On the left flank of Company K, the commander of Company I, Captain Bruce Webb, radioed in reports of Lieutenant Jenkins's troubles in the village of Nam Yên 3 and was given permission to leave his assigned area and attempt to relieve pressure on H Company. To make contact with Jenkins he had to advance through another location, An Cuóng 2. Just as he was about to start the attack, two tanks arrived in support, but they were unable to participate directly, stopped by a deep trench in front of the village. Captain Webb assigned a platoon under Corporal Robert O'Malley to mount the tanks and flank the village on the left, but they hadn't gone far when they fell into a swarm of enemies; after Viet Cong fire killed one of his Marines, the corporal ordered the platoon dismounted and assaulted the enemy position. He and Marine First Class Chris Buchs charged into an enemy trench, killing eight enemies before leaving to reload their rifles. O'Malley and his men returned to the assault, eliminating every enemy they encountered. The corporal was wounded three times, but he continued to attack fiercely and refused to be evacuated until the fighting was over and his men were safe. He made several daring moves under fire to remove fallen Marines from the battlefield. Time and time again, Marine helicopters tried to evacuate O'Malley's wounded but were repulsed by enemy machine guns. Eventually, Ensign Dick Hooton of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 361 landed under heavy fire and evacuated O'Malley and his men. His plane was badly damaged and he had to make an emergency landing on the amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima. O'Malley and his men were landed when his injuries permitted; The corporal would later be the first Marine to receive the highest US military decoration, the Medal of Honor, in Vietnam. Two of his wounded men considered that they were ready to resume the fight, they took rifles and ammunition and managed to return to the battlefield, where they remained until it was all over.

Meanwhile, the rest of Company I managed to defeat the enemy at the village of An Cuóng 2 in fierce combat. Sergeant Jean Piquet did not want to push fate and he finished off the fallen enemies with a shot to the head to make sure they were dead, but Captain Bruce Webb, who considered him inhumane, ordered him to stop. Seconds later, a dead-looking Viet Cong threw a grenade at the I Company command group, killing two Marines, including Captain Webb himself. Ensign Richard Purnell succeeded him in command of the company.

In the H Company sector, Lieutenant Jenkins once again tried to take the village of Nam Yên 3. While encircling the village, a large, well-camouflaged enemy force attempted to flank them. Marine First Class Ernie Wallace saw dozens of what he thought were trees or bushes moving toward him and yelled at his teammates, “Trees! Kill the trees!” and killed approximately twenty-five with his M60 machine gun. Before he finished the journey he would count about forty dead enemies.

While Wallace was still busy, Corporal Dick Tonucci and one of his men, Marine First Class Ronald Centers attacked a machine gun nest that was giving them trouble. They eliminated his crew, but two more enemies took their place. Tonucci and Centers finished them off as well, then charged into another Viet Cong bunker. In attacking the machine gun, Corporal Tonucci left Second Corporal Joe Paul behind, armed with an automatic, to protect several wounded men lying in the open. Paul had been wounded before and could have been evacuated, but he chose to remain on the battlefield. The Viet Cong attacked Paul's position and was wounded four times, but refused to leave his position. In the end, when the Viet Cong were repulsed and the wounded were found safe, Corporal Tonucci carried 2nd Corporal Paul into an evacuation helicopter, but he would die en route. Posthumously he was awarded the Medal of Honor and a ship would be named after him.

The enemy contingent at Nam Yên 3 was too strong and once again Lieutenant Jenkins's attack was repelled at a high cost in life on both sides, so his commander, Lieutenant Colonel Fisher, ordered him to regroup back at LZ Blue. Along the way, one of his sections became separated from the main contingent, so that at the end of the day he had no more than twenty-eight men left ready for combat when he had started the day with almost two hundred.

Around noon an AMTRACKS supply convoy, accompanied by two tanks led by Lieutenant Robert Cochran, left the beach to deliver ammunition and water to I Company, but was ambushed and the leading and trailing vehicles were disabled, immobilizing the entire column. The enemy attacked throughout the day and part of the night and First Lieutenant Cochran, showing extraordinary courage, did everything in his power to keep the column organized, before dying in the fighting. /P>

Platoon Sergeant Jack Marino took the I command to keep fighting with the enemy almost all night. Five marines were killed, but the rest managed to hold their positions. Sergeant James Mulloy was stationed in a nearby paddy field from which he managed to stop small groups of Viet Cong trying to attack the convoy. A refreshment column was organized which was also ambushed and had to abort the mission. Both columns were to be rescued the following morning.

Late in the afternoon the ship carrying the 3/7th USMC from the Philippines came ashore and I Company was helilifted ashore and assigned to reinforce Company I of the 3/3rd USMC. This unit also fell into a scuffle en route and came under heavy mortar fire.

As night fell on the battlefield, the remnants of H Company dug in at LZ Blue, the 3/3rd USMC regrouped, and the rest of the 3/ 7th landed on the shore. Throughout the day, the pilots of Lieutenant Colonel Lloyd Childers's 361st Medium Helicopter Squadron had given excellent support to their comrades on the ground. In a single day, virtually all of the aircraft had been hit, one was completely destroyed, and about half were not airworthy by the end of the day. The ground crew acted heroically trying to keep as many aircraft operational as possible and when a member of the crew fell, another volunteered to replace him.

Lessons from the first encounter

During the night, the enemy took advantage of the darkness to withdraw from the battlefield, leaving behind the bodies of more than 600 comrades. The Americans killed in action numbered 52 Marines, a Navy medic and an Army commander piloting an assault support helicopter. The wounded numbered in the hundreds. There were many heroes that day. The 2/4th USMC and 3/3rd USMC were withdrawn from the battlefield and taken over by the 1/7th USMC and 3/7th USMC, who pursued the remnants of the 1st Rgt. VC for another ten days and came into contact in numerous small but intense fights.

Operation Starlite was a sobering experience for both sides and a major milestone in the US intervention in Vietnam. It was the first major battle of the war , in which two regimental-sized contingents clashed. The Marines found that the combined air and amphibious operations doctrine they had rehearsed for a decade was effective on the battlefield.

The Viet Cong, for their part, concluded that never again, for the duration of the war, should they expose units of that size to combined assaults near the coast. They saw the speed with which the Americans could organize and execute operations and were exposed for the first time to the devastating firepower of combined guns, artillery and naval fire. His response from now on to this challenge would be the "grab them by the belt" tactic, that is, to get as close as possible to the Americans so that firepower would be as dangerous for some as for others. This tactic would also be used against the United States Army just three months later in the Battle of Ia Drang Valley and would continue to be used throughout the war.

The Marines also learned to respect the enemy. Until Operation Starlite, they had generally been "part-time" peasants who would disband at the first show of force. Marine Brigadier General Frederick Karch said, “After seeing them run past our first fire team, I thought they were never going to face each other again. I made a calculation error.”

Bibliography

- Lehrack, O. J. (2004):The First Battle:Operation Starlite and the Beginning of the Blood Debt in Vietnam. Havertown:Presidio.

- National Security Agency. Report released on September 9, 2007 under the Freedom of Information Act. Case Number 7319.

- Peatross, O. F. (1967):“Victory at Van Tuong:An Application of Doctrine”, US Naval Institute Proceedings, September, pp. 2-13.

- Shulimson, J., Johnson, C.M. (1978):U.S. Marines in Vietnam:The Landing and the Buildup, 1965. Washington DC:US Government Printing Office.