A warmongering fervor gripped North and South after the surrender of Fort Sumter in April 1861. The two halves of the country were preparing for war, one to preserve the Union, the other to form an independent nation. The rival presidents, Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis They rushed to create the necessary political and military structures to conduct the war. The leaders of both sides shared the common belief that the conflict would be resolved in a great battle, but spring gave way to summer and the decisive battle did not take place. In mid-summer all eyes turned to northern Virginia:as the federal army crossed the Potomac River into Virginia, the Confederates mustered their forces to hold out.

The resulting battle, the 1st Bull Run , which many had anticipated would be the only showdown of the war, is an interesting study of the early stages of the Civil War. The battle, in which many more men died than ever before in North American history, was for both sides a revelation of what war really consisted of, far from naïve conceptions. or imaginative, and this despite the fact that compared to what was to come, a year later it would be considered nothing more than a minor confrontation. It is not the intention of this article to chronicle the tactical developments of the Battle of Bull Run, but rather to discuss its meaning in the early stages of the Civil War.

Inexperienced soldiers, failed strategies

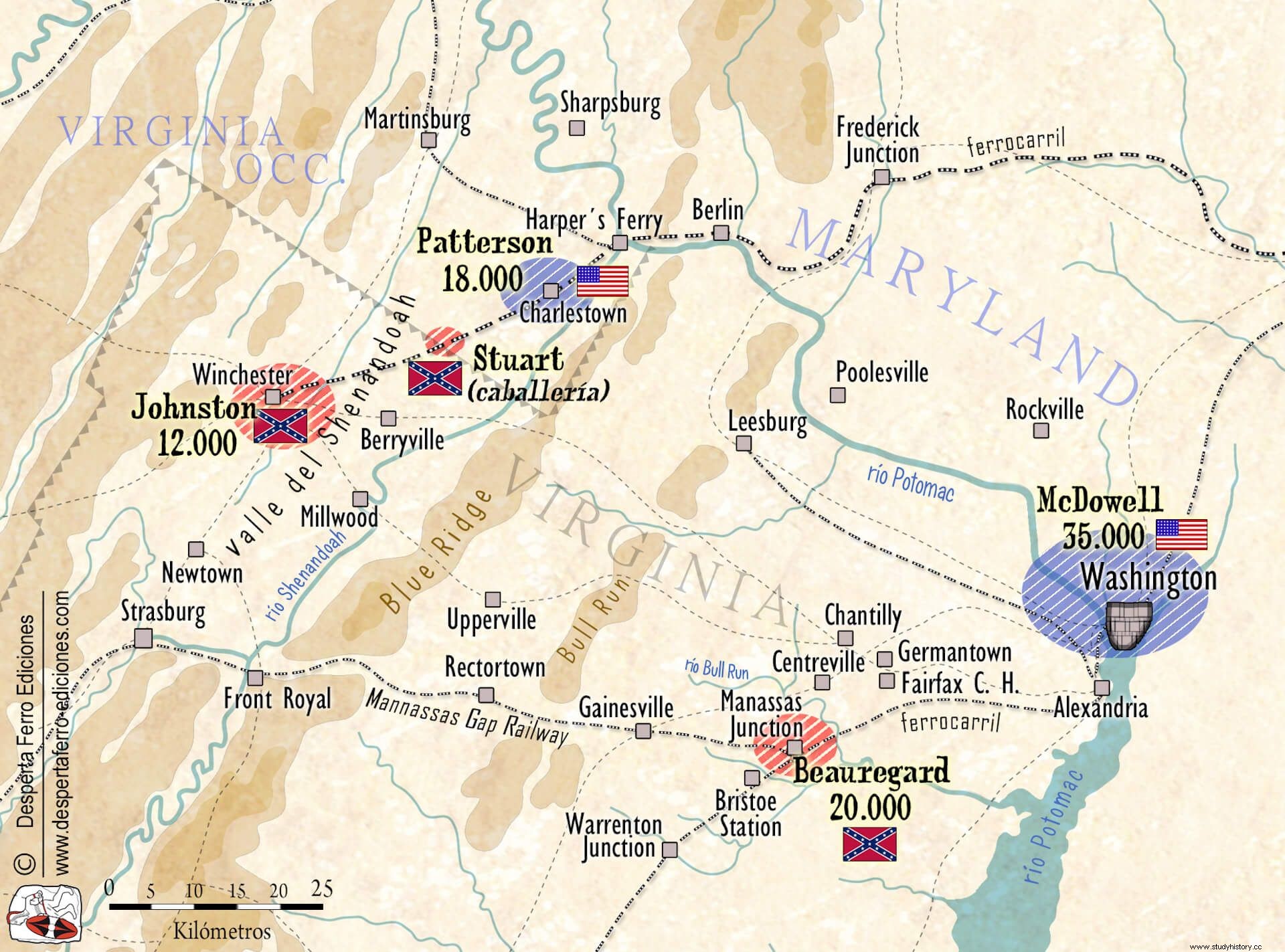

Two features on the map are immediately identifiable with the battle that was fought on July 21, 1861 and both have given this battle its name. Bull Run is a meandering tributary of the Potomac that runs for 53 km from its source in the Bull Run Mountains, which stretch through northern Virginia from southwestern Washington D.C. to the Occoquan River. The creek marks the border of Loudon and Prince William counties, as well as Prince William and Fairfax.

Manassas Junction (Manassas Junction ), in Virginia, is only 25 miles from Washington, D.C., and at this time was a small and insignificant town, except for the fact that the railroad between Orange and Alexandria connected here with the line of the Manassas Gap railway . However, the war had inflamed the importance of the town far beyond its physical and human dimensions, since its railway junction made it a coveted piece for armies dependent on the railway for their transport and supply. Given the circumstances in Virginia in July 1861, the Manassas crossing was vital to Confederate interests, as its railroad junction was essential for the transportation and deployment of troops from the Shenandoah Valley into Virginia, and a presence in Manassas would split the Confederate forces in two and make their cooperation impossible.

Both the river and the small town will gain immortal fame for the two battles that will be fought there in the first stages of the war.

In the early days of the war, the presence of a large Confederate contingent within sight of the Federal Capitol was a constant reminder to Northerners of the seeming powerlessness of the government to do anything decisive that it put an end to the "insurrection". As long as the Lincoln Administration pretended that it was putting down a rebellion and not waging a civil war, this situation would continue to corrode public perception of its conduct of the war. The near isolation of Washington, D.C., the dispute over control of Maryland, and the destruction of several railway bridges that gave access to the city only reinforced this conviction. When Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, Lincoln's personal friend and former court clerk, was assassinated after toppling a Confederate flag flying from the top of an Alexandria hotel, tantalizingly visible across the Potomac, war fervor reached new heights. "To Richmond!" It was the outrage that spread among the northern population, spurred on by the enthusiastic editors of the Northern press. People were unwilling to listen to any more excuses, however valid, for inactivity. Furthermore, as summer approached, the volunteers' original ninety-day enlistment deadline drew to a close, with hardly a single cartridge fired in defense of the Union, and several regiments swore not to serve another hour overtime. their contracts. While his generals messed around and planned strategy, Lincoln's army began to disintegrate. Many regiments, having done their duty, abandoned their posts and returned home, ignoring any appeal to patriotism. Lincoln had to do something, and he had to do it fast.

To General Irvin McDowell he was assigned the task of leading the army against the Confederate forces deployed at the Manassas Crossing. McDowell had no tactical experience, but he was a respected military theorist. He complained that the army was not prepared, or "green", but Lincoln would not listen. The feds were indeed green, the president admitted, but so would the rebels. They were all equally inexperienced. Ignoring the general's practical objections to him, Lincoln demanded that he act.

The subsequent federal plan was really good. In fact, it almost worked, and it probably would have if the army had been properly trained and commanded. McDowell would lead his troops against the Manassas crossing in a multi-pronged attack, setting up a diversion around Blackburn's ford and its stone bridge while encircling the Confederate left flank at Sudley Springs, a strategy designed to keep the Southerners on guard. low as they tried to gauge where the main attack would come from. The key to ultimate success, however, would depend on keeping the only Confederate reinforcements in the area busy in the Shenandoah Valley, a task assigned to Robert Patterson.

To counter the federal offensive, the Confederacy had the forces of Joseph E. Johnston , deployed in the Shenandoah Valley, and those of Pierre G. T. Beauregard , commanding the defenses of the Manassas crossing. Both were among the highest-ranking Confederate officers. Beauregard had become the hero of Fort Sumter while Johnston was a veteran of the old Army with an unblemished record. The Confederates knew they were outnumbered, so their only hope of defeating the Federals was to combine their forces. Ultimately, Johnston was forced to deceive the Shenandoah Federals of his presence in the valley while maneuvering to join Beauregard in Manassas. As long as the Federals posed a threat in the valley, Johnston would be immobilized, and unless he managed to reinforce Beauregard, the Confederates would be seriously outnumbered and vulnerable to outflanking and annihilation. Therefore, the key protagonist of this first campaign, and the only one according to the belief of many, was General Robert Patterson.

Patterson he had the confidence of Winfield Scott, who respected this former brigadier general and veteran of the Mexican War. But Patterson failed to hold Johnston in the valley, and the wily Confederate was able to join Beauregard in time for the fight. After the battle Patterson was blamed for the defeat, and in his defense he wrote a lengthy justification for his actions, despite what many historians still hold him responsible for. The federal plan was complex, but feasible. Beauregard had himself devised an offensive strategy of joining forces with Johnston's and, after destroying McDowell, marching on Patterson in the valley or on Washington, D.C. This plan, vetoed by Richmond, was rendered obsolete as soon as the Federals took over. the initiative.

The Battle of Bull Run

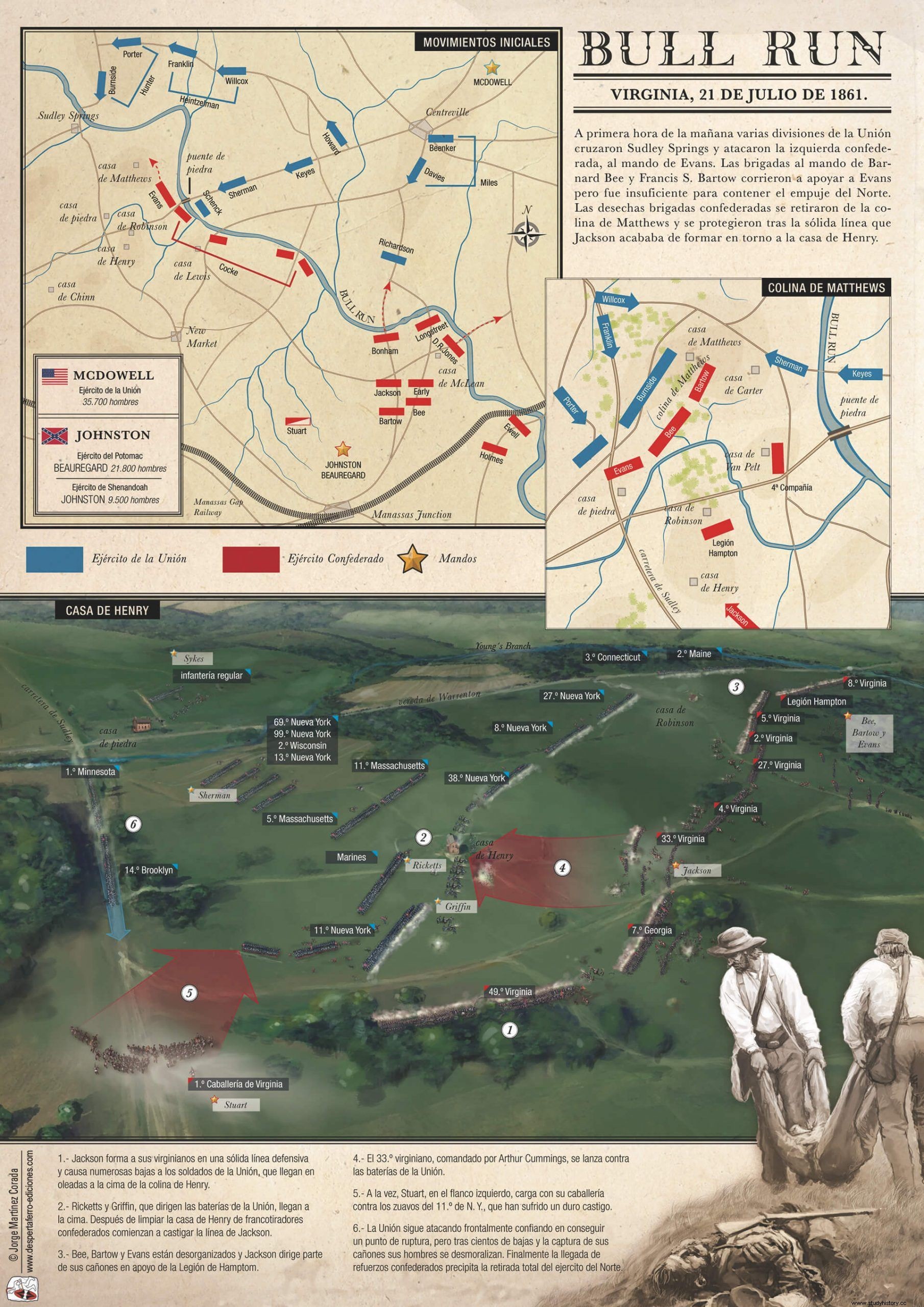

On July 18, McDowell's initial moves triggered a violent skirmish at Blackburn Ford when General Daniel Tyler tried to force the Bull Run through, stopped in its tracks by stubborn Confederate resistance. McDowell then tried to find a new means of crossing the river beyond the Confederate left flank, for which he sent his engineers out on reconnaissance. The resulting plan would mean that his soldiers would have to march even more miles under a scorching sun.

Almost every aspect of this campaign provides perfect examples of what should and shouldn't have been done. McDowell's plan was perfectly reasoned, but it proved too ambitious for an amateur army. Poor coordination among Union forces and Patterson's inability (for whatever reason) to prevent Johnston's departure in support of Beauregard proved decisive. McDowell complained that the inexperience of his troops led to an undisciplined march to the battlefield, and the frequency with which the men left the ranks to gorge themselves on berries, subordinating the momentous importance of the occasion to a brief moment of immediate pleasure. , was a constant distraction for the officers. At one point in the battle, some hungry Confederate soldiers seized the opportunity to grab handfuls of blackberries in the course of a bayonet charge.

Apart from plans and strategies, a series of random factors contributed to the final result, making this battle one of the most interesting in the war. The reigning confusion caused by the identity of the units, dressed in different uniforms and carrying indeterminate flags, conditioned the ebb and flow of the battle. On several occasions the Union victory seemed certain, only to be again and again squandered. There were several instances of friendly fire taking a heavy toll, as soldiers became overly wary of approaching units and would not open fire until they were recognized as enemies, which was sometimes too much. late.

A lull in fighting bought precious time to the Confederates to regroup and prompted the arrival of reinforcements. Unsystematic attacks ordered by unqualified generals, they spoiled the theoretical advantage offered by numerical superiority. What's more, units on both sides were equally disorganized both in victory and after taking casualties or being forced back, effectively being out of the fight, regardless of the cause of their disorder. Finally, these exhausted soldiers, who had given their all on the most stressful day of their young lives, were easily prey to panic.

Although the battle ended in Confederate victory, the balance could have tipped either side. The poor coordination, the amateurism of men and officers and the lack of experience and discipline were decisive. Fierce fighting on Henry's Hill for possession of a Union artillery battery marked much of the confrontation, as did the unlikely resistance of Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson's Virginian brigade. , the energetic charge led by Beauregard himself, and the general lack of coordination of the northern attacks.

Like other battles earlier in the war, what is surprising is not so much the outcome but the determination with which the men on both sides fought. Although Bull Run was small compared to the great battles that would take place, such as Antietam or Gettysburg, it was enough to understand that the Civil War was going to be hard and bloody.

The lessons of Bull Run

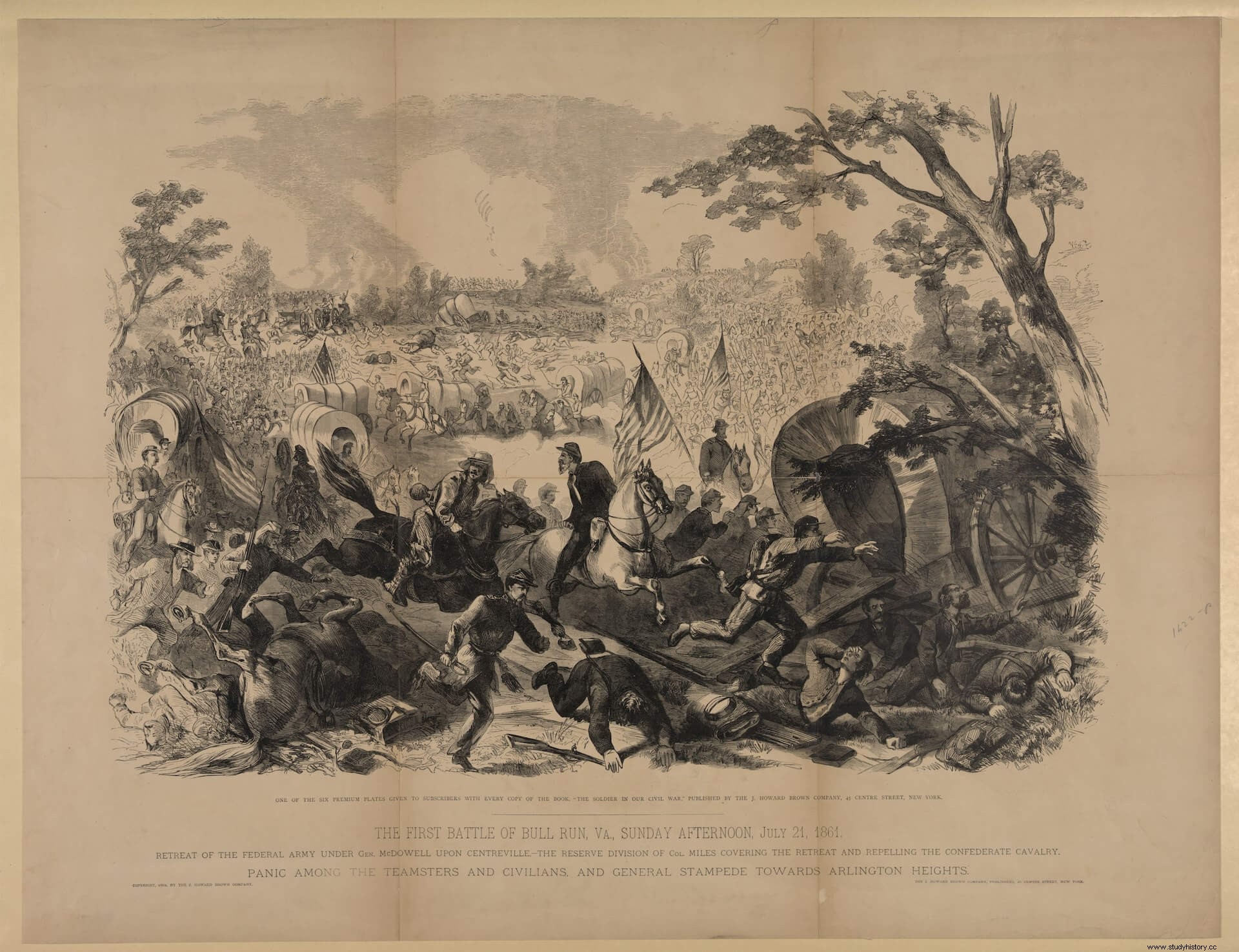

But in July 1861 the war was still an adventure and even the dozens of spectators understood it that way. , among whom were several congressmen and ladies, who came from Washington D. C. to witness the show. They soon realized their folly. New York Congressman Alfred Ely was captured by Colonel E. B. C. Cash of South Carolina, who threatened to shoot this "bloody son of a bitch" who hadn't wanted to miss out on the fun.

The battle was a great adventure and an important learning experience for both armies and for the people on both sides. Many participants will recall their pre-battle attitudes with disgust. The "green" soldiers, both blue and grey, emerged from combat as veterans, with a better understanding of what war really was and what roles they would be expected to play, and both victor and vanquished sensed that a single battle, not even a campaign , would not be enough to solve the crisis that had dragged them to arms.

Union Corporal Elisha Hunt Rhodes, of the 1st Rhode Island Infantry, was elated during the march to confront the rebels. On July 16 she wrote, "Well, I hope we succeed and give the rebels a good thrashing." Her tone was less optimistic a few days later. After the disaster and flight of the federal army, Rhodes wrote:

As day broke, the exhausted Rhodes could see, to his relief, the nation's capital. The exhausting retreat was over. The citizens of Washington, alerted to the situation, rushed to offer her help. Corporal Samuel D. English, of the 1st Rhode Island, recalled that “the cheers we received through the streets of Washington seemed to breathe new life into the men who, on arrival at camp, collapsed to the ground and instantly lost their lives. most of them were asleep.”

An officer in the 14th Brooklyn later recalled the effects of the battle on the new soldiers:

According to another New Yorker «we were defeated before we reached the battlefield, because after such a long march, with nothing to eat and nothing to drink except water so thick that it barely It was leaking, you can understand that we were not in very good condition to fight.”

The Confederate experience it was very different. According to Private Edgar Warfield of the 17th Virginia, the victory was a source of unbridled jubilation for the rebels. George Wise wrote "What a glorious day Sunday was for the South! When the rout of the enemy rushed over the long line of the Bull Run, a shout of joy went up! Oh, how big it was!”

The implications of the battle They had a long range. In the North, the initial despair turned into a firm determination. Diarist George Templeton Strong succinctly summed up the feelings immediately following the battle:"Today will be remembered as Black Monday. We have been completely and shamefully defeated, beaten and beaten by the secessionists. But on July 22, President Lincoln issued a call for another 500,000 volunteers, dramatically increasing the size of the Union army. As he prepared to draw on the nation's strength, he searched for a new general to lead his forces to victory.

On the Confederate side, Mary Chestnut, wife of a former US Senator from South Carolina, now General Beauregard's aide, was far more moved by relief for the safety of her husband and her grief for the fallen than for the enthusiasm of victory. "Worry has made us so miserable," she wrote, "that the feeling of revulsion was almost impossible to bear." Rebel Secretary of War John B. Jones was elated to hear of "this costly but glorious victory" that thrilled all of Richmond. "All men seem to think that the course of war will turn from that day on enemy territory, until we achieve a glorious peace." But he was also cautious and he foresaw that «the North, far from desisting from the achievement of its determined purposes, will be stimulated to renew its preparations on a scale of a magnitude never seen before»

For those directly involved, the battle will be iconic. William T. Sherman he came under enemy fire for the first time in his life, for throughout his long military career he had always shied away from battle, and he learned to respect the volunteer soldiers he commanded, despite the lackluster use he made of them.

Congressman John A. Logan, also a witness to the battle, returned to Illinois, where he uttered patriotic slogans in support of the Union and accepted the rank of brigadier general, becoming one of the ablest political generals of the war.

Thomas J. Jackson he will go down in history for his defense of Henry Hill and for the nickname, Stonewall ("stone wall"), named after General Barnard Bee, who died in battle. While Jackson would become a legend, Joseph E. Johnston and Pierre G. T. Beauregard would use this early victory to try to solidify their positions in the Confederate Army. Beauregard, who will emerge from the battle as a hero, the most popular idol in the South, will see the luster of him fade almost immediately. Similarly, Joe Johnston, who could be considered the real orchestrator of the Confederate victory, fell out of favor with the Jefferson Davis Administration. Ego and pettiness were common elements of the character of both generals, flaws that would make them unable to serve their commander-in-chief. Neither was able to put his country and his cause above his own interests. These discords born of the euphoria of victory will have long-term consequences for the Confederacy, for which the battle offered unequivocal proof of its superiority against the Yankees and, ultimately, of the triumph of his cause.

Bull Run was an exceptional training ground for both sides. All participants will benefit from the teachings of battle, and many of them will end up commanding brigades, divisions, and even corps and armies. Some will fall, but others will lead the campaigns that finally decided the war. Notable figures in the Union include Oliver O. Howard, Charles Griffin, Ambrose Burnside, Orlando Willcox, Erasmus Keyes, William B. Franklin, and Fitzjohn Porter. Confederate luminaries included James Ewell Brown Stuart, Jubal A. Early, James Longstreet, Nathan Shanks Evans, and Edward Porter Alexander.

Perhaps the most significant event resulting from the battle was the appointment of General George B. McClellan as commander of the Union armies. Known as Little Mac He brought with him a whole load of strengths and weaknesses that would define the federal war effort for more than a year, and from the raw material that had suffered the humiliation of Bull Run he fashioned a disciplined army.

The Union General-in-Chief, Winfield Scott , later assumed responsibility for the failure. He was aware that the army was unprepared and wanted to wait until his own plans could mature before going on the offensive, which would have required waiting several months to train and discipline the three-year conscripts who joined the army. rows. However, Scott's good judgment bowed to the president's wishes. The defeat demanded an explanation and a solution. Criticism was fed to Patterson and Scott himself would soon retire, giving way to the energetic McClellan.

Americans are hasty, impatient and demanding people, they want what they want and when they want it. Success validates the demand, but failure requires a scapegoat. They are short-memory people, quick to forget success or failure as soon as their demands have been met, making it difficult to manage long-term political and international affairs. Although Americans expect and demand success, they lack the will to see beyond it, forgetting that success sometimes hides behind apparent failure and that only the test of time is the true measure of results, and that wanting something, or demanding it, does not have to be accompanied by the desired result. As true today as it was in the days of the Civil War, generals like Scott, McDowell, Patterson and those who succeeded them understood this bitter truth.

Bibliography

- Ballard, Ted (2007):Staff Ride Guide for the Battle of First Bull Run , Washington D.C., Center for Military History.

- Davis, William C. (1977):Battle at Bull Run , New York, Doubleday &Co.

- Detzer, David, Donnybrook (2004):The Battle of Bull Run, 1861 , Orlando, Harcourt.

- Hennessy, John (1989) The First Battle of Manassas, An End to Innocence July 18-21, 1861 , Lynchburg, H.E. Howard, Inc.

- Rafuse, Ethan S. (2002):A Single Grand Victory, The First Campaign and Battle of Manassas , Wilmington, SR Books.