In the early 1850s, Russia tried realize its main objective in the region by taking control of the Turkish straits and increasing its domain over the Black Sea . As a pretext, the Russians used the dispute over the management of Christian holy places in Ottoman Palestine. Russia and France disputed the right to care for pilgrims and faithful Christians who lived under the sultan's authority. The Ottoman Empire, threatened by Russian expansion, forged an alliance with Western powers because Britain and France understood that Russian plans endangered their economic and political interests in the Levant.

The outbreak of the war known by historiography as the Crimean War o Eastern War was the result of the capture of Moldavia and Wallachia –Danubian principalities that were the object of rivalry between Russians and Turks– by the czar's armies, in July 1853. In response, on October 16, 1853 the Ottoman Empire declared war on Russia. In the first phase of the conflict, from October 1853 to March 1854, the war actions were carried out exclusively by the armed forces of both States. The climax of warfare at sea was the Battle of Sinope on November 30, 1853, the last major engagement in the history of sail-powered warships.

The Russian Navy

On the eve of the outbreak of the Crimean War, the core of the Russian fleet in the Black Sea It was made up of ships of the line. These had been built to modern plans and of solid shipbuilding materials. Thanks to their strong complement of gunners and good training, the Russian crews would not give in to ships of this class belonging to the British Royal Navy and the French National Navy.

In 1853, the Black Sea Fleet had fourteen ships of the line and six sailing frigates, seven steam frigates (with paddle wheels on either side), four corvettes ships, twelve brigantines, twenty-eight gunboats, and dozens of small sail-powered auxiliaries. Two sailing ships of the line, two steam corvettes and one gunboat were in the final stage of construction at the Nikolayev shipyard. In total, in the Black Sea, the Russians had 61 ships, on which 2,500 guns and more than a hundred smaller units without artillery were deployed. A total of about 35,000 sailors, including 1,450 officers, served on the ships. Nearly 20,000 more sailors were sent to serve in the defense of the coast.

On the one hand, Prince Aleksandr Ménshikov was appointed commander-in-chief of the naval and land forces of the Russian Empire in the Black Sea basin. On the other hand, the commander of the Black Sea fleet and ports was the elderly Admiral Moritz von Berg, who had no combat experience. Vice Admiral Vladimir Kornílov exercised the functions of chief of staff of the fleet. , one of the most talented Imperial Russian Navy officers of his generation. Crew morale was high and sailors were well trained. Most of the credit for crew training goes to Admiral Mikhail Lazarev , commander of the Black Sea fleet and ports between 1834 and 1851.

The traditions of the Lazarev school, whose characteristic elements were the introduction of conscious discipline and the elimination of corporal punishment, found continuity in his most outstanding students:Vladimir Kornílov, Pavel Nakhímov and Vladimir Istomin, who stood out during the Crimean War both in naval actions and during the defense of Sevastopol. On the initiative of Admiral Lazarev, a large shipyard was established in Nikolayev and a smaller one in Novorossiysk. In Sevastopol, the main operational base of the Black Sea Fleet, modern docks were built and the construction of a large shipyard called Lazarevska began.

In the early 1850s, the Russian admiralty knew that the age of the sailing ship was coming to an end. The tsarist government, however, was late in introducing steamships into service. Without a doubt, this was the result of the economic backwardness of Russia, which prevented the Eurasian country from competing effectively with Western powers in the field of naval technology. In 1842, thanks to the efforts of Admiral Lazarev, five steam frigates (with side paddle wheels) were purchased for the Black Sea Fleet in England (Kherson, Krim, Bessarabia, Gromonosets and Odessa). However, these ships were used mainly as a means of transportation and practically did not participate in training maneuvers. In the decade before the outbreak of the Crimean War, the Black Sea Fleet received only one ship that fully met the technical requirements of its time . It was a side-wheeled steam frigate named Vladimir, built in England in 1848 under the supervision of Vladimir Kornilov. She had a strong complement of artillery (two 24.5 cm guns, five 21.4 cm guns, four 15.2 cm guns and two 13.8 cm guns) and reached a speed of eleven knots. She was the most modern ship of the Black Sea Fleet during the Crimean War, comparable to the ships of this class of the navies of Western powers.

The Ottoman Army

In the first phase of the Crimean War, the only opponent of the Russian Black Sea fleet was the Turkish Navy . Its core consisted of sailing vessels, including five ships of the line, ten frigates, nine corvettes and twelve brigantines. They were supported by five steam frigates (with side wheels) and about thirty small auxiliary sailing craft. The sultan also had at his disposal an Egyptian fleet :three ships of the line and four sailing frigates. Part of the units, including a ship of the line and five frigates, were temporarily out of service while necessary periodic repairs were carried out. In addition, three ships of the line were under construction and were supposed to enter service in the spring of 1854.

In total, the Ottoman navy numbered forty-eight gunships with more than two thousand guns. Istanbul was the base of the main forces of the Turkish fleet, and the commander in chief of the navy was Admiral Mahmud Pasha . One of the most distinguished officers to serve in the navy was the Englishman Adolphus Slade, who had been the sultan's personal adviser on maritime affairs since 1839 under the name of Musavera Pasha. In the opinion of foreigners who had the opportunity to observe the exercises of the Turkish fleet, the training of the crews left much to be desired and morale was low. The state of the arsenals, shipyards and weapons factories was also not satisfactory.

First skirmishes

On the eve of the outbreak of war, the Black Sea Fleet was ordered to transport ammunition from the Crimea to the Caucasus coast. The task was carried out by the squadron commanded by Vice Admiral Nakhimov, who between September and October 1853 transferred the 13th Infantry Division (more than 16,000 soldiers with two light artillery batteries) from Sevastopol to Sukhumi. Eleven transports protected by the core of the squadron, which consisted of twelve ships of the line, were used in the landing operation.

After the start of hostilities, Vice Admiral Nakhimov was ordered to patrol the waters between Anatolia and Crimea. On November 16, 1853, the Russians achieved their first success in the war. The frigate Bessarabia (of Lieutenant Piotr Szczegolev) took over the Turkish steam freighter Mecihire Tacihiret, which, after being taken to Sevastopol, joined the Russian fleet under the name of Turok. On November 17, the first battle between steamships in history was fought. in the port area of Penderaklia, in Anatolia. The Russian frigate Vladimir (under the command of Lieutenant Grigory Butakov) bombarded and forced the lowering of the flag to the Egyptian steam frigate Pervaz Bahir (of Rear Admiral Said Pasha). The damaged Ottoman fleet ship was towed to Sevastopol and, after the necessary repairs, was incorporated into the service of the Russian fleet under the name of Kornilov.

The battle of Sinope and the destruction of the Ottoman squadron

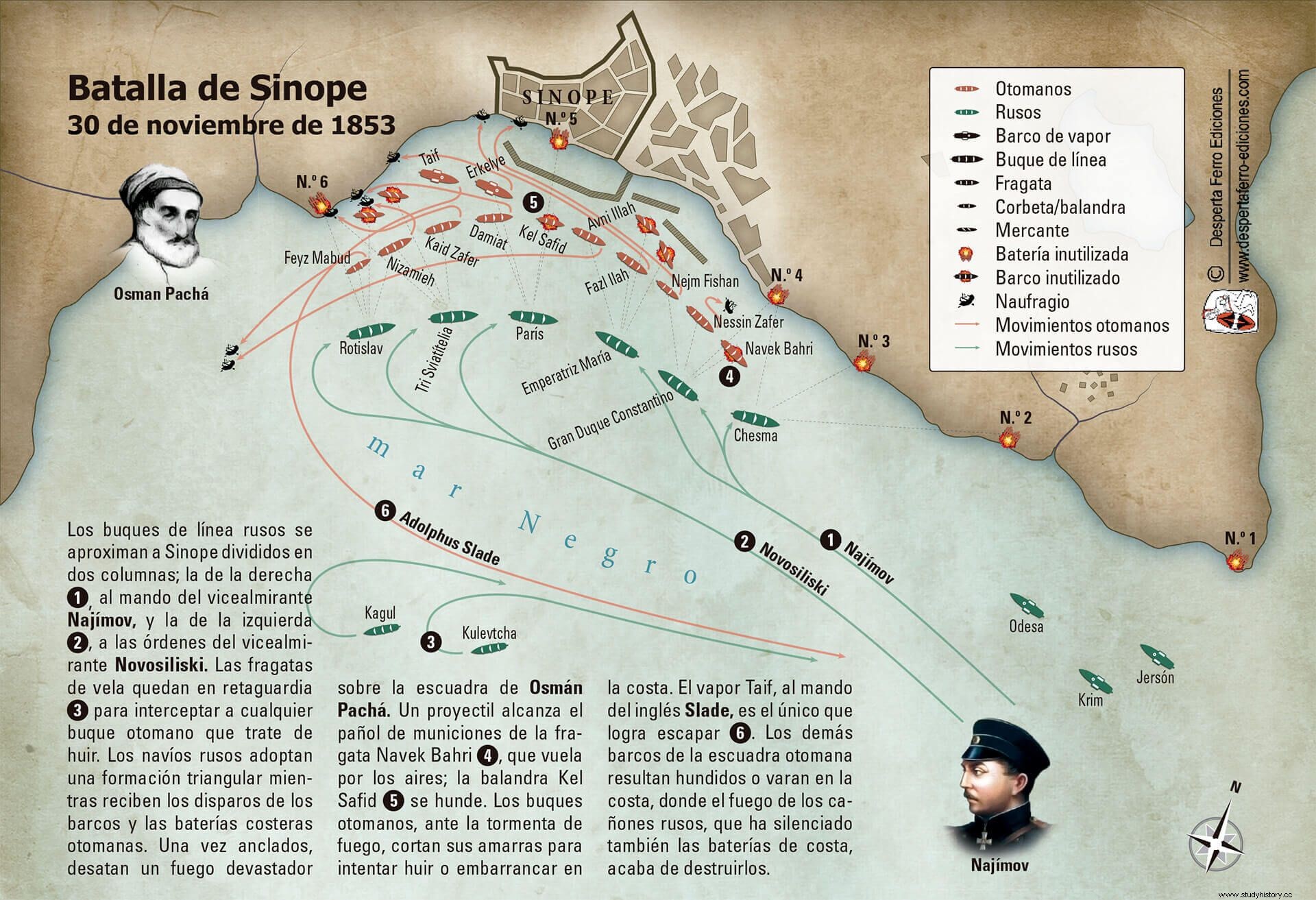

On November 23, 1853, Vice Admiral Nakhimov's squadron, patrolling the waters off the Anatolian coast, encountered an Ottoman squadron anchored in Sinope Bay. Nakhimov organized the blockade of the port and, having obtained ammunition, began preparations for the great battle. On the eve of the clash, the Russians had six ships of the line (Empress Maria, Chesma, Rostislav, Paris, Grand Duke Constantine and Tri Sviatítelia) and two sailing frigates (Kulevtcha, Kagul). The Ottoman squadron was commanded by a veteran of the Battle of Navarino (1827), Vice Admiral Osman Pasha, and consisted of six sailing frigates (Nizamieh, Avni Illah, Navek Bahri, Damiat, Nessin Zafer and Fazl Illah), two steamer (Taif and Erkelye), two sailing corvettes (Feyz Mabud and Nejm Fishan), one sloop (Kel Safid) and two transports.

Nakhimov's squad had a clear advantage in terms of artillery, because Osman Pasha could only challenge the 716 cannons deployed by the Russians with 472 of his own, and of a much smaller caliber. The Russian Vice Admiral's plan was based on a direct attack by his ships of the line against the Ottoman fleet. The Russian ships were to enter the Sinope Bay and, after approaching within gunshot range, drop anchor to avoid wind drifts. Two shots from the flagship were supposed to be the signal to open fire. The Russian frigates were ordered to maneuver at the entrance to the bay and prevent the Turkish steamboats from slipping away.

November 30, 12 noon, Russian ships of the line entered Sinope Bay forming two columns . The right included Vice Admiral Nakhimov's flagship, the Empress Maria, the Grand Duke Constantine, and the Chesma. The left column was led by Paris, followed by Tri Sviatítelia and Rostislav. They were greeted by the cannon fire of the Ottoman units, aligned in a crescent and supported by coastal batteries. The Turkish gunners, in order to stop the attack, aimed mainly at the rigging of the Russian ships. After closing within gunshot range, the Russian ships of the line dropped anchor and opened fire on the enemy's ships and batteries. The Empress Maria, after an exchange of fire with the frigate Avni Illah, the flagship of Vice Admiral Osmán Pachá, forced the Turkish ship to run aground. The Russian flagship then bombarded the Fazl Illah frigate, causing numerous fires and forcing her to dive to land.

Grand Duke Constantine and Chesma riddled the frigate Navek Bahri and caused an explosion in the ammunition lockers which resulted in the sinking of the Turkish ship. The two Russian ships of the line then turned their guns on the corvette Nejm Fishan, which sank after burning. The Paris, leading the second column, sank the sloop Kel Safid and forced the frigates Damiat and Nizamieh to run aground. The Tri Sviatítelia, for her part, she shelled the frigate Nessin Zafer and caused fires that forced her to throw herself ashore. The Rostislav, the last ship in the left column formation, directed her fire on the corvette Feyz Mabud and forced her to run aground. The Erkelye steam frigate and two transports moored in the Sinope port were also victims of the accurate cannon fire of the Russian ships.

The battle of Sinope, lasting four hours, concluded with the absolute destruction of the Ottoman squadron , which lost twelve ships, including seven frigates (six sailing and one steam), two corvettes, a sloop, and two transports. The Turks also suffered heavy loss of life. Of the 4,220 Ottoman sailors who participated in the Battle of Sinope, some 4,000 were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. Among the latter was the commander of the squadron, Vice Admiral Osmán Pachá. The steamship Taif, commanded by Musaver Pasha (or Adolphus Slade), barely survived from his ships, who, using the speed of his ship, managed to escape from the Russian frigates Kulevtcha and Kagul maneuvering along the outer layout of the port of Sinope. Despite the pursuit, which was joined by the steam frigates (Odessa, Krim and Kherson) of Vice Admiral Kornilov's squadron, which rushed to Nakhimov's aid, the Taif reached the Istanbul base without any problems. .

Russian losses at the Battle of Sinope were relatively small. 38 sailors were killed and 235 wounded. No Russian ship was sunk, but all were damaged. The Empress Maria, the hardest hit (sixty hits), was towed by the steam frigate Krim to the Sebastopol base. The ships of the line Grand Duke Constantine, Tri Sviatítelia and Rostislav, who had been left with their sails depleted, were also towed there. The rest of the ships of the line (Paris and Chesma), which had suffered minor damage, returned to Sevastopol on their own.

Keys to the Russian triumph

An analysis of the Battle of Sinope leads to the conclusion that the Russian advantage in naval artillery had a decisive influence on the final result; the 472 guns deployed on Ottoman ships and 24 coastal artillery pieces were measured against the 716 guns in Nakhimov's squad. The qualitative advantage was also important, since the Russian guns surpassed the Turkish ones in caliber; of the former, 76 were 68-pounders, 412 36-pounders and 228 24-pounders, against only two 77-pounder Turkish guns, 4 38-pounders and 160 29-pounders (in the ships). Without a doubt, the use of high explosive grenades by the Russian naval artillery had a significant influence on the outcome of the battle. Artillery grenades with primitive impact fuses had been invented in the 1830s by the French general Henri-Joseph Paixhans, and since 1841 artillery adapted to fire grenades had begun to be introduced into the armament of ships belonging to the Imperial Russian Navy.

According to Vice-Admiral Nakhimov's reports, it appears that at the Battle of Sinope, the Russian ships launched a total of 16,873 shells, including some 2,000 grenades, which easily pierced the sides of the Turkish frigates and caused the total destruction of the wooden ships. Nakhimov's leadership skills also contributed to the end result. The detection of the Turkish squadron and, subsequently, the rapid concentration of forces skilfully carried out, provided the Russian squadron with the necessary qualitative advantage (ships of the line against frigates) that, finally, led to a spectacular victory.

The detailed Nakhímov battle plan , which he personally detailed to the ship's commanders during the court-martial on the eve of the Battle of Sinope on November 29, 1853, deserves special recognition. The great value of this plan is attested by the idea of using a two-line formation crossing the crescent on which Ottoman ships had lined up. The assumptions of the plan, which provided the commanders of the ships of the line with a significant degree of operational freedom, confirm Nakhymov's great confidence in the navigational and combat skills of his subordinates. The excellent cooperation of the Russian ships confirmed the high level of training of the commanders and crews.

The operational and tactical errors of the side ottoman they also contributed to Russia's success. Vice Admiral Osmán Pasha, after his troops were discovered by the Russian reconnaissance forces, did not try to seize the operational initiative despite the fact that, between November 23 and 29, 1853, he had a clear advantage in the number of ships and cannons on the Russian forces blockading the port of Sinope. Therefore, he could have tried to break the blockade and, if necessary, fight on the high seas, where the Turkish frigates would have had an easier time manoeuvring. A battle against a stronger opponent would certainly have been risky for the Russian side, because Nakhimov's reconnaissance force blockading Sinope was quite far from his base in Sevastopol, while the Ottoman squadron would fight close to his operational base. Another error of Vice Admiral Osmán Pasha was the incorrect positioning of the ships in Sinope Bay, which made it difficult, or even impossible, for part of the coastal artillery batteries to fire. The Ottoman squadron commander made no attempt to make better use of the resources of his steamships (advantage in maneuverability and speed), something that Vice-Admiral Nakhimov feared to a certain extent, who had no such units at the start of the battle. .

Consequences

The victory at Sinope ensured Russia's domination of the Black Sea . The disruption of shipping links along the Anatolian coast prevented the Ottoman Empire from transporting ammunition to the war theater in the Caucasus, greatly deteriorating the Turkish military situation in the region. Paradoxically, however, Sinope's victory had dire political consequences for Russia . Britain and France, worried by Russian military successes and fearful that their political and economic interests in that part of the world would be threatened, agreed to armed intervention on the side of the weakened Ottoman Empire. The entry into the conflict of the Western powers, which had modern armed forces, tilted the final outcome of the war in favor of the anti-Russian coalition.

The Battle of Sinope was the last great confrontation between sailing fleets . The ineffective pursuit, by the Russian sailing frigates, of the Turkish steam frigate Taif, the only battleship of the Ottoman fleet to survive the battle, was an indication, with all its symbolism, that the era of sailing was coming to an end and would soon be replaced by the age of steam and iron.

Bibliography

- Gozdawa-Gołębiowski, J. (1985):Od wojny krymskiej do bałkańskiej (Działania flot wojennych na morzach i oceanach w latach, 1853-1914). Gdańsk:Wydawn; Morskie.

- Langensiepen, B.; Güleryüz, A. (1995):The Ottoman Steam Navy, 1828-1923 . Annapolis:Naval Institute Press.

- Tarle, E.W. (1953):Wojna krymska, t. I–II. Warszawa:Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej.

- Treue, W. (1980):Der Krimkrieg Und seine Bedeutung für die Enstehung der modernen Flotten. Herford:Mittler.