As impressive as the conquests of the Mongol horsemen throughout the length and breadth of that enormous land mass that is Central Asia, the challenges they had to face on the limits of their great empire were ever greater. Among the setbacks suffered, no expedition suffered such severe punishment as the attempts to conquer Japan by the grandson of Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan .

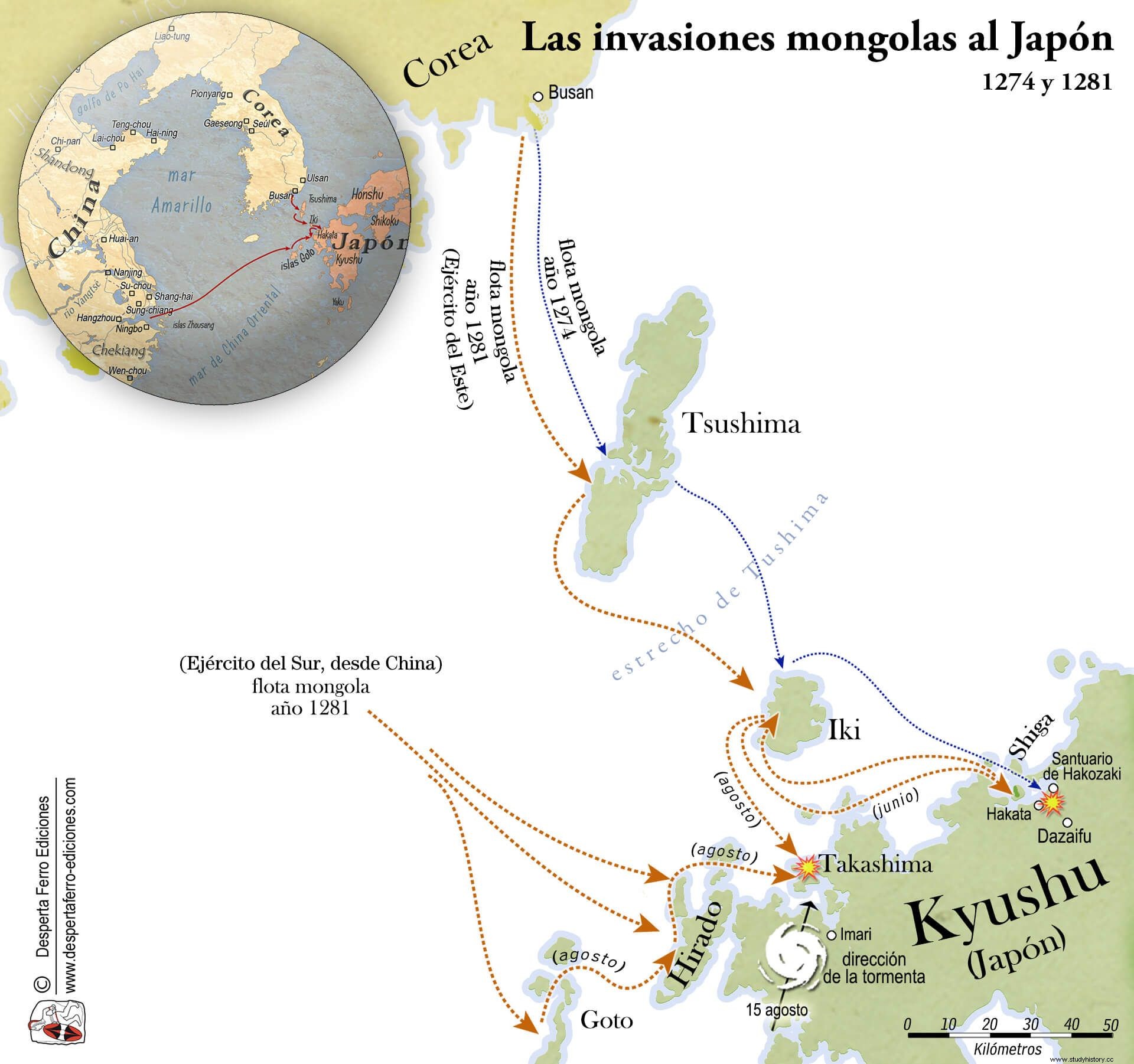

The strategic objectives pursued by Kublai Khan with his first invasion of Japan (1274) are obscure to say the least, as are the motivations behind his desire to involve Japan by force in the broader context of Far East politics. His tactical plan However, it is clear:the invading fleet would first attack the islands of Tsushima and Iki, thus safeguarding their lines of communication, and then land on the mainland in Kyushu, in Hakata Bay. Japanese plans, supported by reliable intelligence reports, were to meet all attacks by local samurai contingents numbering 4,000-6,000 men. The estimates of Japanese combatants given by the Mongol sources are very different since, partly as a way of justifying the defeat of 1274, the Yuan Shi gives us the incredible figure of 102,000 defenders.

The first of the Mongol invasions of Japan (1274)

The invading fleet set sail from Korea on November 2, 1274 for Tsushima, where 8,000 Mongols, transported in 900 ships, landed at two different points. Coinciding with the Mongol advance, a fire mysteriously broke out in the island's Hachiman temple. The fire was quickly extinguished, and the incident was saved from being a bad omen when Governor So Sukekuni News reached him that a flock of white doves had been sighted nesting on the roof of the temple. The dove was Hachiman's messenger, so it was interpreted that the god of war had set Hachiman's own temple on fire as a warning and not as a harbinger of doom. So Sukekuni's troops, consisting of 80 mounted samurai and his followers, engaged in bloody combat with the invaders from 4 pm onwards.

For the first time, the Japanese and Mongols would face their diametrically opposed tactics in battle. Many Mongols, whose ranks had been disordered by a grove of trees, perished under the accurate arrows of Sukekuni and the samurai under his command. Saito Sukesada, one of Sukekuni's closest followers, especially excelled in the battle, killing at least one high-ranking Mongol officer. However, the brave Sukesuda ended up being isolated from his comrades and, after a tough fight in which he broke his sword, he met his end when he was hit first by a stone –probably thrown by an enemy catapult– and then by a shower of arrows. , three of which stabbed into his chest. In the midst of the fighting, two men took a boat and managed to sneak through the Mongol fleet to bring a message ashore:the war had begun.

The Mongol victory was total . After setting fire to the buildings in their path and massacring most of the inhabitants, at 4 pm on November 13 the Mongols left the devastated Tsushima for a much smaller island, Iki. In this case the defense had been delegated to Taira Kagetaka, which operated from its base in Hinotsume. Unlike the mighty stone fortresses of later Japan, Hinotsume's "castle" would be no more than an elaborate stockade with watchtowers and fortified gates, yet reliable enough for Kagetaka to entrust its protection to the wives and families of the samurai who went with him to face the invaders on the beach.

As at Tsushima, Iki's defenders were greeted by heavy volleys of arrows, fired to the thunderous accompaniment of Mongol drums and gongs. Iki's samurai fought to exhaustion, and as night fell the Mongols retired to their ships to rest. However, the next morning the castle was surrounded by a huge Mongol army, deployed under numerous red flags. Desperate, the women of the garrison joined the defense.

When one of Hinotsume's gates was breached by the Mongols, and hopes of receiving aid by sea were exhausted, Taira Kagetaka prepared to lead his men in a end charge. However, as they approached the gate with their bows drawn, they encountered a human shield made up of dozens of his countrymen, who had been tied to each other by ropes inserted through holes in their hands. Abandoning their bows and arrows, the samurai drew their swords and charged at the Mongol horde. They were soon outmatched and, faced with the certainty of defeat, Kagetaka retreated into the castle to commit suicide along with his family. Resistance broken, Iki was swept away. The Mongol fleet then set out for Kyushu, though not before hanging some unfortunate prisoners from their riddled hands on the prows of their ships.

The mainland defenders were already on high alert from the news coming from Tsushima and Iki. The samurai sent there by order of the Kamakura shogunate to meet the Mongol assault had foreseen that the most propitious place for an enemy landing at Dazaifu would be the sheltered coast of Hakata Bay. , from where, once a beachhead was established, the nearby regional government headquarters would be within easy reach. The two commanders in charge of the defense were Shoni Kagesuke and Shimazu Hisatsune, who took up positions in the vicinity of Hakozaki Hachiman's temple.

Mongol detachments landed in the western area of the bay , from where they planned to march east along the coast to take Hakata before moving inland along a valley to Dazaifu. All available sources suggest that the fighting was initiated by the Mongols, confusing the defenders because of how unfamiliar they were with their tactics:the way the Mongol soldiers marched on foot in large and comparatively dense groups, protected by shields, driven by war drums and surrounded by much noise, including the use of explosive bombs, required a profound revision of traditional Japanese combat techniques. The small groups of fighters in which the Japanese operated could not hope to storm the enemy formations and come back alive, although some tried. Worse yet, the samurai tradition of selecting an opponent worthy of your arrow was severely curtailed, and the handful of glorious accounts of individual accurate shots that took place during battle should be viewed as the exception rather than the rule.

The fight that took place over the next 24 hours was fierce, though seemingly brief and uncoordinated. In little more than a day the Mongols established a beachhead, advanced towards Dazaifu... and disappeared completely. In the Hachiman Gudokun chronicle we can read:

Several points to consider emerge from this story, beginning with the ridicule of the young Shoni Kagetoki when he "officially" declared the battle had begun. The Mongols, having experienced Japanese tactics (small-group attacks, individualized combat orientation) at Tsushima and Iki, and having won crushing victories in both cases, could afford to be contemptuous of Japanese formalities. Hakata also seems to have been the first place where explosive bombs were used that, already wrapped in paper or in an iron casing, caused fear among men and horses, although more because of the thunder of the detonations, together with the roar of gongs and drums, than for the real damage that the explosions could cause. The compiler of the Hachiman Gudokun is equally impressed by the control exercised over the Mongol army by the generals through drums and gongs. Nothing comparable to Mongol infantry tactics had been seen in Japan since the abandonment of Chinese-style infantry armies centuries ago, and organization into squads divided by weapon type will not make its reappearance in warfare in Japan for several years. centuries later. The use of poisoned arrows is another noteworthy innovation, and we should also note the mention that many Mongol fighters rode on horseback, befitting their steppe heritage.

However, despite this show of superiority, the Mongols withdrew their forces the following day. Although, of course, the Japanese claimed to have repulsed them, it is more likely that the first of the Mongol invasions of Japan was a scouting and reconnaissance operation:the ground had been surveyed and the fighting ability of the samurai put to the test. . With this vital information at his disposal, Kublai Khan was able to prepare for a second visit with which he hoped to capture Japan for himself.

The second of the Mongol invasions of Japan (1281)

The Khan's plans for the 1281 invasion drew on the experience of 1274, especially regarding the need to "pacify" Tsushima and Iki before attempting to land in Hakata and to the fierce resistance they had encountered in those three theaters of operations. The main difference between the two invasions was the much larger scale of the second and the intention to establish a permanent occupation of Japan, evidenced by the fact of transporting farm implements on Mongol ships. The military and naval resources of Song dynasty China were now fully under Mongol control, allowing Kublai Khan to launch his massive army in a two-pronged attack launched from Korea and southern China. This force was also increased in many different ways, such as the recruitment of those sentenced to death, who could commute their sentences by enlisting in the invasion army. Even those in mourning for the death of their parents – something very serious in China at the time – had to return to arms after 50 days.

For their part, the Japanese placed almost all their trust in a stone wall erected during peacetime along the shore of Hakata Bay, while Tsushima and Iki would be left to fend for themselves. When the vast Mongol army finally reached the coast, the defensive wall proved to have been a wise investment. As soon as some of the Mongol ships landed men and catapults, volleys of arrows fell on them, fired from the wall by both foot archers and mounted samurai, who rode their mounts on the back slope to the defensive line. Casualties among the invaders must not have been high, but they were unable to establish a beachhead.

Unable to land, the Mongols instead took possession of the two islands of Shigashima and Nokoshima, in the bay. From there and from their own ships they prepared to launch raids against Hakata, but found themselves attacked by the Japanese instead. Shiga Island was connected to the mainland by a strip of sand, which the samurai used to surprise their enemies. In addition, attacks were launched, often at night, from small boats, the masts of which, fixed to a shaft in the middle of the deck so that they could be lowered, were sometimes tilted forward to be used as a makeshift bridge over which to climb onto the rocks. Mongolian ships. Grappling hooks were also used to hold onto the flanks of enemy ships, and there are even mentions of samurai swimming over Mongol ships.

Among the accounts of these attacks we find one referring to Kusano Jiro that appears in the Hachiman Gudokun. Jiro led a night attack on a Mongol ship that had become isolated, amid a hail of missiles from what the Hachiman Gudokun calls ishiyumi (literally “stone arches”), probably Chinese siege ballistae modified to fire stone missiles, on a low trajectory, instead of bolts. The mast of Kusano Jiro's ship was used as a boarding platform, after which a fierce battle ensued in which the Japanese managed to set fire to the Mongol ship and return with 21 enemy warheads.

In this way, the attack on Hakata was repelled , but to their horror the Japanese soon discovered that this army represented only a small part of the huge Mongol army that was headed for Japan. At the beginning of the seventh lunar month, the great fleet of the already pacified Song dynasty south of the Yangtze, which according to sources consisted of 100,000 men aboard 3,500 ships, began to arrive in Japanese waters over a very wide area. . Immediately contacts were established with the fleet that had sailed from Korea, and had returned to Iki, and began the complicated process of reordering the two combined fleets, a process that culminated at the end of that month, when the fleets were put back on track. march on to their next target, Takashima Island, far to the west of the stone wall defending Hakata and close to Imari Bay in the Matsuura area.

The Japanese chose to refocus their strategy on the attacks aboard small boats that had given them such good results, and on August 12 they launched a first offensive in the vicinity of Takashima, where a fierce naval battle took place which lasted throughout the night. Unfortunately we don't have the details, but this operation could have been a repeat of the Hakata attacks, albeit on a much larger scale. However, the result was the same, the Mongols were unable to land in Takashima and were confined to their ships, which will be a determining factor in the final result:no matter how much courage the samurai had shown, the image that has survived of Mongol invasions of Japan is that of Imari Bay covered by hundreds of shipwrecks as a result of a typhoon called kamikaze (“divine wind”).

The fact that a typhoon hit the Mongol fleet is indisputable. While the ships remained anchored between the island of Takashima and Kyushu, in Matsuura, a tremendous wind arose. The boats near the coast collided with each other and were dragged by the protection ropes with which they were attached. The waves swept over the decks and many men perished by drowning as it was impossible to rescue the survivors. Some ships sank, others crashed into rocks or ran aground. Those in deeper water cut their anchor lines and tried to ride out the storm.

There is some dispute as to the actual loss of human life, although it seems logical that they must have been enormous. However, the destruction of the fleet was a more determining factor in abandoning the invasion than the human losses. A Korean source, quite precise regarding the losses among his compatriots, indicates that of the 26,989 men who left with the Army of the Eastern Route, 7,592 did not return, a number of casualties that, including deaths, prisoners and missing persons, would reach the 30th%. Chinese and Mongolian sources are less accurate, but give a casualty rate of between 60 and 90%. Another hugely explicit piece of evidence about the scale of the debacle is the behavior of the expedition leaders, who decided to regroup what was left of the invading fleet and head back to China and Korea, leaving behind thousands, if not tens of thousands. , of soldiers and sailors found adrift on driftwood or washed up on the shores of the Matsuura Peninsula or on Takashima itself. The Japanese immediately surrounded the survivors and massacred them. After such devastation, the second of the Mongol invasions of Japan came to a dramatic end.

The myth of the kamikaze

As the good news spread among the courtiers of Kyoto, victory was interpreted as a sign of divine intervention, a perception that only grew over time. The kamikaze had blown, and this became a source of pride as the time of the Mongol invasions began to be seen as a unique period in Japanese history in which everyone, from the emperor to the last Japanese, was united in the goal common way of dealing with the foreign threat. Despite the roots of this idea, the highest expression of the myth of the Mongol invasions, the truth is that this national crisis failed resoundingly when it came to uniting Japan in pursuit of a common goal, and in the following half century the Hojo family , who had ruled at the time of the invasions, was defeated and ousted from power.

However, the mythological character of the Mongol invasions of Japan did not stop growing over time. It is significant that in the literary works of subsequent centuries the expression shinkoku (“land of the gods”) appears more and more profusely to refer to Japan, an exceptionally safeguarded land. In parallel, a growing polarization began to develop between the perception of the Japanese warrior and the demonized foreigners. As late as 1853, the year before Japan opened its gates to the outside world after three centuries of isolation, prayers for the subjugation of foreigners were recited whenever ships were sighted in Japanese waters, prayers based on curses hurled against Japan. the Mongol invaders 600 years earlier. Finally, when Japan was again threatened by foreign invasion in 1945, the desperate defense carried out by suicide pilots shared both the spirit and the name of the kamikaze . They were the heirs of the “divine wind” , and they did not hesitate to immolate themselves by crashing their planes on the decks of US aircraft carriers in the vain hope of emulating their ancestors, who had managed to repel the terrible Mongol invasion.

Bibliography

- Conland, T.D. (2011):In Little Need of Divine Intervention:Takezaki Suenaga’s Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan , Cornell.

- Delgado, J. P. (2008):Khubilai Khan’s Lost Fleet:In Search of a Legendary Armada , McIntyre.

- Turnbull, S. (2010):The Mongol Invasions of Japan 1274 and 1281 , Osprey.