It is therefore not surprising that the importance of the site was recognized early; According to the geographer Strabo, a native of nearby Pontus, the legendary Babylonian queen Semiramis founded in Zela a stronghold. The city grew as a communications hub when the Persians connected it with one of the royal roads with which they articulated their immense empire. Later, after the fall of the Achaemenids, Zela became a prey of considerable military importance. Thus, when Mithridates VI the Great , king of Pontus, fought against Rome in 89 a. C., one of his first measures was to conquer Zela and kill all the Romans who were there. It is also not surprising that when Rome forced Mithridates to make peace at Dardanus in 85 BC. C., the surrender of Zela was among his demands. To ensure that Zela did not fall into Pontic hands again, Sulla ordered a fortress to be built there.

These precautions were for naught when the ever-shaky peace broke down again in 73 BC. C. (there had already been a short but intense second war in the previous years). The Romans managed to expel Mithridates from his kingdom, but the Roman general Lucullus got bogged down in an unpopular war against Tigranes the Great of Armenia . Tigranes was the son-in-law of Mithridates and gave him shelter until he could return to Pontus. Like any province that had felt the weight of Rome's misrule in the Lower Republic, the Pontics enthusiastically joined the banners of Mithridates, who tried to retake the fortress of Zela. It fell to a certain Gaius Valerius Triarius to defend the Roman possession against his previous owner and, longing for all the glory, he did not wait for Lucullus to return to his aid. Triario was confident that he could claim victory with his corps of hardened – albeit prone to mutiny – legionnaires, but he was wrong. The Romans were outmatched and defeated in a pitched battle. This first clash of Pontics and Romans at Zela is not well documented in the sources, since those that have survived are Roman, and the Romans enjoyed recounting their victories to succeeding generations more than describing their defeats. However, the destruction of a Roman army was a rare and remarkable achievement in the ancient world, and we can be sure that even after being reconquered by the Romans, the people of Pontus would have been proud of their deed.

The reconquest of Pontus fell to Gnaeus Pompey or, as he preferred to be known, Pompey the Great . Pompey expelled Mithridates to the kingdom of the Bosphorus, north of the Black Sea, and it was there that this inveterate enemy of Rome died in 63 BC. C. (or in 62 BC according to others), betrayed by his son Pharnaces. He was quick to make peace with the Romans.

Pharnaces

Over the next decade Farnaces he quietly ruled the kingdom of the Bosporus; yet another from Rome's collection of client eastern kings, nominally independent but in reality subjects of the Republic. But Pharnaces was his father's son, and he remembered the days when Pontus had reigned over all of Asia Minor and disputed with Rome the dominion of Greece. Pharnaces also recalled that one of the reasons for his father's success had been that for many years Rome had been too distracted by civil wars to throw all her might against Pontus. It is likely that Pharnaces never abandoned the intention of retaking the ancestral kingdom from him in the event that the grip of Rome weakened.

Thus, when in 49 a. With civil war once again threatening to bring the Republic to its knees, Pharnaces saw his chance. Pompey, the former conqueror of Pontus, contended with his former colleague of the triumvirate Julius Caesar for owning Rome. Hoping to outnumber the small but fearsome contingent of veterans that Caesar had brought from Gaul, Pompey "dried up" Asia Minor of troops. Here was Pharnaces' opportunity. As the historian Dio Cassius points out (History , XLII.9):

Exploiting Roman weakness in Anatolia, Pharnaces attacked south from the Bosphorus kingdom. As his campaign progressed news came of Pompey's defeat at Pharsalia, Greece, but by then Pharnaces had shown his cards and he had no choice but to continue the rebellion. Fortunately for the cause of Pontus, Caesar followed the defeated Pompey to Egypt, where he remained after Pompey's assassination. He did it first to bring his candidate, Cleopatra, to power, and then to enjoy the fruits of victory, in a flirtation that ended with a son of the Egyptian queen, whom he named Caesarion. Q>

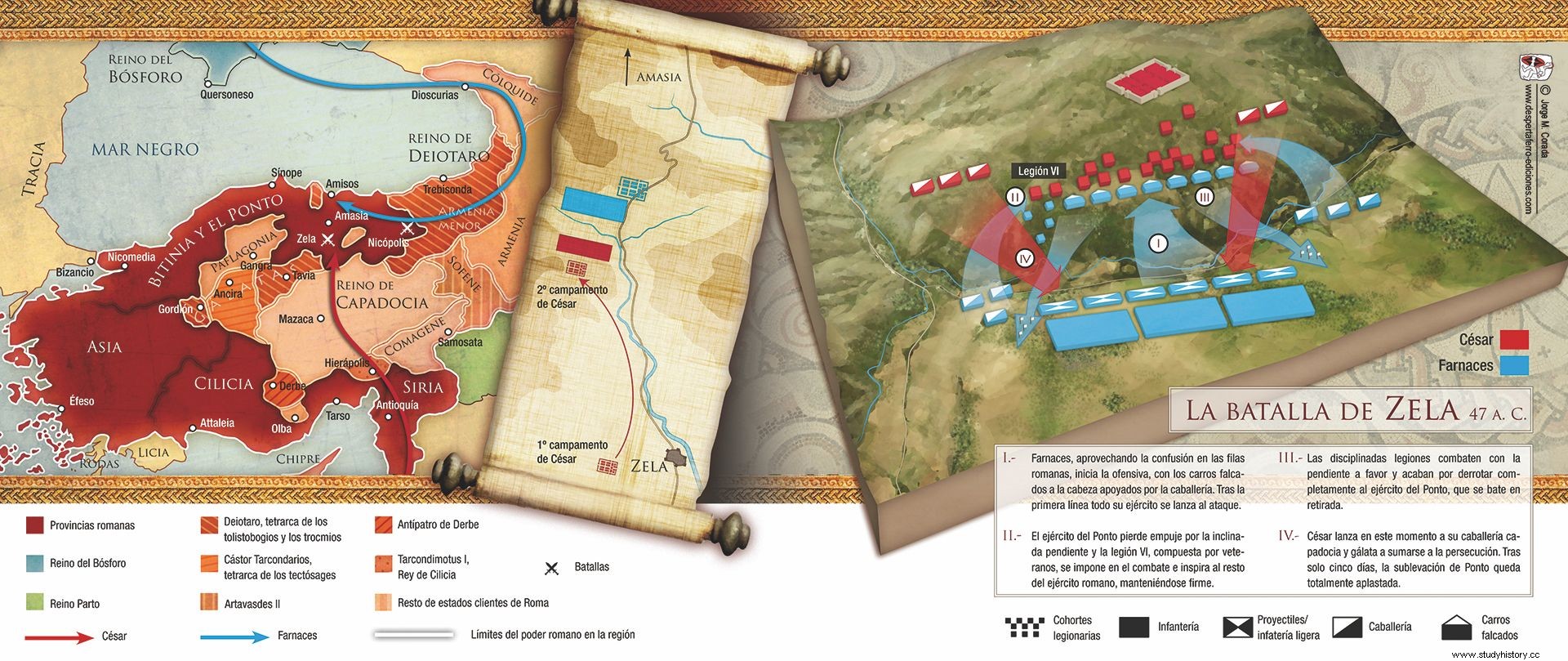

With Anatolia still short of Roman troops and Caesar occupied, Pharnaces managed to reoccupy part of Pontus with little resistance. Colchis, on the shores of the Black Sea, was just as easily occupied. The situation in Galatia was uncertain, since its king Deiotaro he had supported Pompey. As Caesar's enemy, Deiotaro could not afford to further destabilize Caesar's position through military action, so the Galatians stood by while Pharnaces attempted to seize Armenia and most of Cappadocia.

By the time urgent envoys reached Caesar, Pharnaces he was in the process of retaking some cities once ruled by Mithridates but now part of the Roman province of Bithynia. In fact, Pharnaces was close to rebuilding his father's empire . This forced a response from Caesar, and although not yet ready to act in person, he sent a force of legionnaires under C. Domitius Calvin. Calvin informed Deiotaro that the best way to appease Caesar was to ally his army with that of Rome, and taking in addition some troops from the client king Ariobarzanes, he immediately marched against Pharnaces, but was totally defeated at Nicopolis. Q>

Caesar springs into action

This defeat pushed Caesar into action, because Pharnaces also retook the ancient capital of Pontus, the city of Amisos. Until then Farnaces had arguments. He could argue that Asia Minor had been dominated by Pompey's faction and that he was fighting the Pompeians and not Rome. He could also argue, and it was true, that he had tried to negotiate with Domitius Calvin but that Calvin had rebuffed his attempts at peace and gratuitously attacked him. But when he took and plundered Amisos, Farances captured and killed all the Romans of military age, and castrated the youngest to be sold as eunuchs. Since the war with Pompey was over, this attack on the Romans unequivocally made Pharnaces an enemy of Rome.

Caesar arrived in Syria, and from there he marched towards Asia Minor with his famous celerites , the quickness of movements that he so often took his friends by surprise. King Deiotaro had gone to meet Caesar when he landed, and he was formally pardoned for his "rebellion." From then on he and his men served in the expeditionary force. Plutarch tells us that this consisted of “three legions ”, but in reality the Caesarian army was rather less substantial than that figure would seem to indicate. The VI Legion, which had accompanied Caesar from Alexandria, was badly depleted by constant campaigning, barely numbering a thousand men. But these men, all veterans accustomed to victory, provided a solid backbone that would prove essential. The other two legions were the remnants of the force defeated by Pharnaces at Nicopolis, thus less reliable. Not mentioned by Plutarch, the Galatians formed a fourth "legion", as some of Deiotaro's troops were armed and trained in Roman fashion. This legion had also been battered at Nicopolis, but was probably the largest unit. Caesar no doubt recruited more troops as he advanced into Cappadocia, including the light cavalry for which this country was famous.

The size of the forces that Farnaces had at his disposal is unknown. Surely he would have Scythian archers and spearmen from the Greek cities of the Bosphorus, along with levies recruited from the warlike people of Pontus. A rough estimate could be around 25,000 men, but the truth is that the true size and composition of the armies that fought in Zela have been lost. What we do know is that Pharnaces' army included falcate chariots. These could be formidable machines if deployed at the right time, but the Romans had encountered them in the Mithridatic Wars a generation earlier and had convincingly overcome the threat.

If Pharnaces was concerned by the news of Caesar's arrival, his subordinates had long feared it. Asander, the regent that Pharnaces had left on the Bosphorus, decided that it was preferable to face the army of his own king than the legions of Rome, and rebelled. Pharnaces was on his way north to deal with this uprising when news of Caesar's coming forced him to turn around to face this more immediate threat.

To block Caesar from entering Pontus , Pharnaces settled on an elevation about three Roman miles from Zela (about 4.5 km). From there one could see the victory monument erected by Mithridates to celebrate his triumph over Triarius in 67 BC. C. It is clear that this previous battle was considered important for both the Romans and the Pontics. Pharnaces saw in the victory of his father an inspiration, and the Romans a shame that had to be avenged.

When Caesar arrived, Pharnaces sent ambassadors to him to propose peace, while at the same time he prepared for war by fortifying the rise where his army was encamped. But Cesar could play this game. He let the ambassadors know that the conflict could be resolved peacefully, and while the peace talks were taking place, he took the opportunity for his army to maneuver without obstacles to a more advantageous position for the confrontation.

The Battle of Zela

Caesar established his first camp about five miles (about 7.5 km) from the Pontus army, and from there he surveyed the terrain to discover that the valleys separating the two armies They could be easily defended. As Caesar assumed that he would have to fight on the rise that Pharnaces had fortified, he decided to at least take possession of said valleys first. A quick night march brought his troops into the same strong position that Mithridates had used years before to launch his army against the Romans, well positioned to seize the valley between the two armies.

To level the field in front of the rise where Pharnaces was entrenched, Caesar sent the slaves of the camp to gather bundles of firewood –fascines – to fill the holes or ditches that the pontics had dug. Meanwhile, as was the Roman custom, the legionnaires had begun to fortify their camp.

Caesar hadn't counted on Pharnaces' sky-high morale, nor on the fact that he was both impetuous and generally evil . Therefore, when he saw the army of Pontus emerge from their secure position and prepare for battle, he did not pay much attention to it. He thought the king was either making a show of force to boost his man's morale or, at best, preparing to harass the slaves who were collecting wood for the fascines . Even when he saw the enemy arrayed for combat and beginning to advance, Caesar thought the maneuver was a bluff. He went against all military logic for an army to leave a secure position, advance through a narrow valley that denied it its numerical advantage, and then attack a veteran army arrayed in a strong position. So Caesar only put the first rank of his soldiers on alert, and ordered the rest to continue working on fortifying the camp, confident that once Pharnaces had shown his men that he was not hiding from the Romans, the army would go on. Pontus would return to his barracks.

But the Pontics drew near, and when the army enemy began to ascend the slopes of the hill that the Romans were fortifying is when Caesar finally realized that Pharnaces was serious. There was a horrible bewilderment among the Roman ranks when the legionnaires, who had been imperturbably digging in and ignoring the approaching enemy, were ordered to drop their entrenching tools and immediately prepare for action.

This rare moment of confusion in the Roman ranks was the ideal moment for Pharnaces to launch his falcate chariots , and that's what he did. The chariots added to the confusion, further supported by cavalry. Things might have gone awry for the Romans if the fighting had been on flat ground, but fortunately for Caesar the chariots, charging uphill, quickly lost thrust, while the slope helped the legionnaires launch their missiles until the vehicles came to rest. stop. The chariots had done their job, which was to keep the Romans in confusion while the rest of the Pontic army followed to charge through the hastily formed enemy ranks. The result was that, although the Pontics were charging uphill, the legions had trouble dealing with this fierce and unexpected assault. The fighting in the center of the line was long and hard, and the result doubtful.

But the same was not true on the Roman right wing, where the VI Legion was stationed. As veterans these men had been more agile in their deployment, and thus more ready when the attack hit them. Years of campaigning with Caesar had taught them to be prepared for the unexpected, so at least they were ready and waiting for the onslaught. This flank quickly overcame their attackers, and with the VI Legion setting an example, the rest of the army stood their ground.

Once the surprise attack wore off, the inherent advantages of the Roman legions came into play. Disciplined troops trained in hand-to-hand fighting will eventually win out over the most enthusiastic of amateurs, especially if the latter fight uphill. The advantage of the legions having the slope to their advantage made it even easier to push the enemy back, and once the Pontus army began to give ground, their cohesion disappeared. Soon Pharnaces' troops fled with as much energy as they had previously charged. The narrowness of the valley hampered this undisciplined retreat and, having had quite a scare, the legionnaires were not about to be lenient. Although the sources do not confirm it, it is probable that Caesar launched his Cappadocian and Galatian cavalry at this time to join in the slaughter. The fortified elevation served as no protection, as the Romans were hot on the heels of the fleeing enemy too close for the Pontic commanders to mount any attempt at resistance. Farnaces soon realized that the journey had been lost and fled with a small number of bodyguards on horseback; later his rebel governor Asander would find and assassinate him. The rest of the army had nowhere to flee, and the Caesarian narrator (Alexandrian War , LXXVI) points out dispassionately that “[…] many soldiers were killed, many others were crushed to death during the flight.” Some four hours after Pharnaces had led his men out of his fortified camp, the Pontus uprising had been completely crushed. Cesar had been in the country for five days. The brevity of the campaign inspired his famous report to the Senate: Veni, vidi, vici ; I came, I saw, I conquered.

Caesar later commented scornfully that Pompey had been fortunate to earn his reputation against foes as poor as these he had encountered. This disdain was unjustified, for the Pontus army had fought hard and defeated Domitius Calvin at Nicopolis. It was not the fault of the troops that a bad general had led them into an untenable position.

Caesar erected a great monument to his victory at the Battle of Zela. He deliberately placed it next to the one Mithridates had erected to commemorate his over the Romans in 67 BC. Because of its size and grandeur, Caesar made sure that his monument surpassed that of Mithridates, and in fact his victory was also more significant:after this battle Anatolia remained in Roman hands for centuries, even longer than the city of Rome itself.

Primary sources

- Caesar, The Alexandrian War . Sarpe. (Trans. Goya Munián, J.).

- Casius Dio, History. Gredos . (Trans. Candau Morón, J. M., Puertas Castaños, Mª. L.).

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives , Caesar . Gredos. (Trans. Bergua Cavero, J, Bueno Morillo, S., Gúzman Hermida, J. M.).

Bibliography

- Goldsworthy, A. (2007): César, the definitive biography. The Sphere of Books, Madrid.

- Keaveney, A. (2007):The Army in the Roman Revolution . Routledge.