The life and work of Pierre Lepoivre , an officer in the Army of Flanders and a civil architect, always loyal to the Spanish Crown, make clear the great transformations that military architecture and engineering underwent in the transition from the 16th to the 17th century, which significantly altered the art of war.

Military revolution and fortification in Flanders

The modernization of urban fortifications in the Netherlands began in 1534 with Emperor Charles sending the engineer Frate da Modena, better known as Jacopo Seghizzi, who visited and studied the defenses of the southern border of the province and projected new fortifications at Bouchain, Avesnes and Le Quesnoy. In the 1540s and 1550s, due to the shift of the focus of warfare from northern Italy to the Netherlands, the medieval castles of Gravelines, Renty and Namur, the walls of Thionville, were modernized, and urban defenses were erected in several southern cities:Mariembourg, Hesdin, Charlemont and Philippeville.[1] All these works were aimed at safeguarding the Netherlands against an external enemy. However, beginning in the 1560s, growing social unrest and the spread of Protestantism gave rise to a new need:that of consolidating and guaranteeing real control over unruly inner cities. The first to openly raise it before Felipe II was Fray Lorenzo de Villavicencio, a spy of the king in the province, who, before the departure of the Duke of Alba for Italy, pointed out to the monarch the remedy to quell the popular uprisings that were taking place:

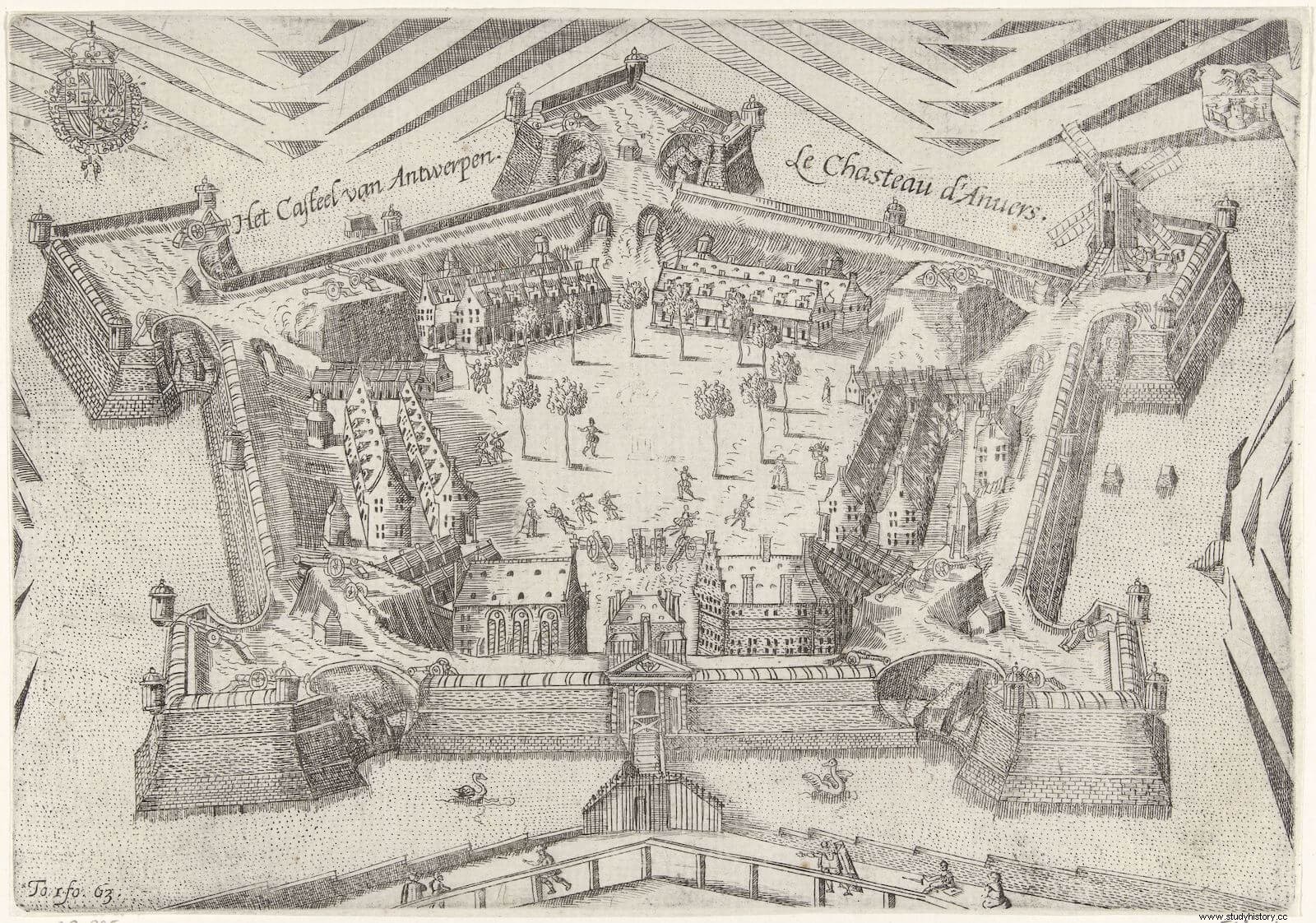

In November 1566, shortly after the end of the iconoclastic fury, the Duke of Alba successfully defended the urgency of erecting citadels before Philip II's Council of State bastions in the main cities of the Netherlands . Governor Margaret of Parma echoed his opinion and, in the summer of 1567, shortly before the duke's arrival, approved the construction of bastioned citadels in Antwerp, Valenciennes, Flesingen, Maastricht, 's-Hertogenbosch –or Bolduque–, Utrecht, Amsterdam, Groningen and Nijmegen.[3] Margarita de Parma commissioned two projects for the most important of these citadels, that of Antwerp –the most populous and richest city in the Netherlands–, to two prestigious architects, the Bolognese Francesco de Marchi and the Flemish Jacques van Oyen. When the governor was replaced by the Duke of Alba, however, the design and construction of the important fortress fell to the duke's military engineers:Francesco Paccioto – architect of the design of the citadel of Turin, then the most renowned in Europe – and Gabrio Serbelloni.

Paccioto's design, so similar to that of the citadel of Turin that he excused himself from sending plans to Felipe II –“because His M. already has those of Turin, which are made like those”–, was harshly criticized by Serbelloni and by other trusted men of Alba:Chappino Vitelli, general field master, and the also engineer Bartolomeo Campi. However, the duke defended the chosen design, a pentagonal plan with a bastion at each corner, not only because of its solidity, but also because Paccioto managed to adjust the space so that it was unnecessary to demolish an excessively large number of houses, when “á Cabrio Gervellon seemed to him that a large number of houses worth more than a million would be thrown to the ground, which [Paccioto] affirms that it was nonsense, since without this expense and damage the square has comfortably grown to more than three hundred houses.” [4]

Qualified in the 17th century as "undoubtedly the most incomparable modern fortification work in the world" by the Englishman John Evelyn,[5] the citadel of Antwerp marked the beginning of a revolution in the art of fortification in the Netherlands and across Europe that altered the way wars were fought. In the words of Mahinder S. Kingra, although in the 1590s most of the two hundred cities of the Low Countries still had medieval defenses, the rapid spread of the Italian trace in the region “restored and consolidated the supremacy of defensive structures in European warfare, which firearms had temporarily undermined.”[6]

The strongholds, some of them capable of resisting months of siege, they asserted control of the territory, its resources and its communication routes, which made the war of Flanders a war of sieges, as Alba himself was able to verify in 1572 and 1573, when his army was held back for months before the walls of Mons and Haarlem and resolved to employ a strategy of calculated terror to save time , men and resources to the royal coffers. Thus, when justifying the sack of Malinas, Alba wrote to Felipe II:"example is very necessary for all the other towns that have to be collected, so that they do not think that each one of them is necessary and the army of V. M., which would be an infinite business.”[7]

Pierre Lepoivre, life and work

It is in this context that Pierre Lepoivre appears, a bourgeois native of Mons who , shortly after turning twenty, already ran his own architecture studio . In 1567, upon the arrival of the Spanish troops, he was required by the Duke of Alba to collaborate in the service of Paciotto, Serbelloni and Bartolomeo Campi in directing the works of the citadels of Antwerp and, shortly after, those of Groningen and Coevorden, which the duke had erected during his campaign in Friesland in 1568.

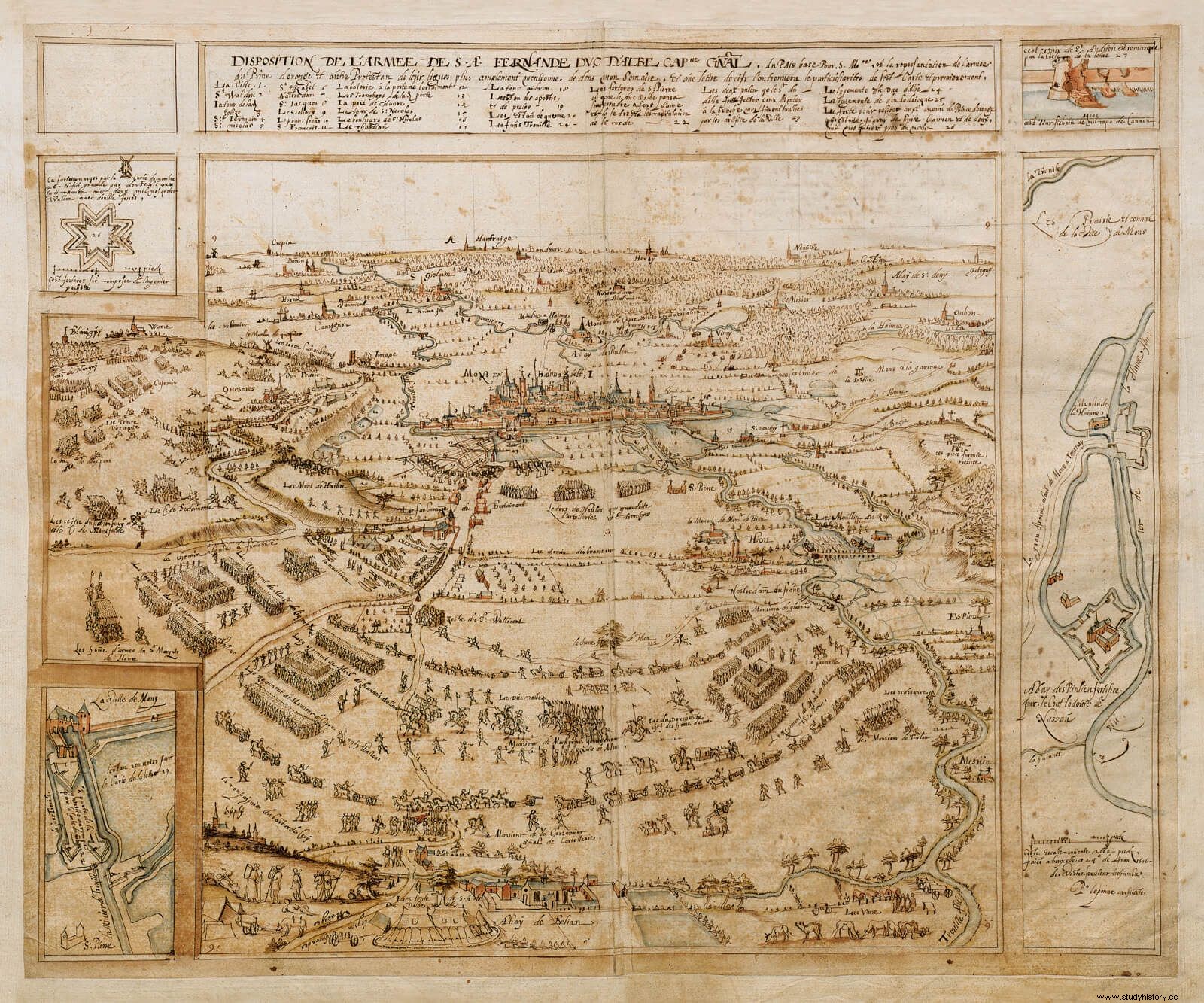

The following year, Pierre Lepoivre accompanied Count Ernest from Mansfeld to France with a body of Hispanic troops who collaborated with the French Royal Army in the fight against the Huguenots, and in 1572 and 1573 he participated as an engineer in the sieges of Mons and Haarlem . On the death of Luis de Requesens in 1576, Lepoivre remained loyal to the Crown despite the fact that two of his relatives had been executed by order of the Court of Tumults, and he continued to serve in the Army of Flanders until the 1590s. In 1579 he served as assistant to Gabrio Serbelloni in the siege of Maastricht, and in the following five years he was assistant to the successive chief engineers of Alejandro Farnesio, Properzio Barozzi and Giovanni Battista Piatto.[8]

Pierre Lepoivre's responsibility was in crescendo , and soon began directing projects commissioned by Farnese . In 1581 he built a fort at Outrijve on the banks of the Scheldt to control shipping traffic between the rebellious cities of Tournai and Oudenaarde, and in 1583 he was the architect of the pentagonal fort that forced the surrender of Ypres. For all these reasons, in 1582 he was forced to close his Mons studio due to the impossibility of simultaneously attending civil and military projects. His services in the following decade were rewarded on November 16, 1593 when he was appointed court engineer and cartographer, as well as maître artiste du roi , a position for which he received an annual salary of 400 pounds, plus an allowance of 3 guilders a day – later raised to 4 – for his travel expenses.[9]

After the peace of Vervins with France (1598), Lepoivre once again alternated civil architecture with military architecture and designed and directed the embellishment works of the residences of the Archdukes Albert and Isabel in Binche and Mariemont, where he erected gardens inspired by those of Aranjuez. He also carried out renovations at Coudenberg Palace and various noble residences such as the Hotel de Croy and the castles of Hoogstraten and Westerloo. His last campaign service was in 1603, when he participated in the defense of Den Bosch against the army of the United Provinces. Before retiring in 1611 he modernized the defenses at Le Quesnoy, Landrecies, Avesnes, and Philippeville, drew up a new design for the fortifications of Cologne, and traveled to Franche-Comté to inspect the defenses at Dôle and Gray.

Lepoivre dedicated the last years of his life to art and, between 1615 and 1622, he produced his crowning work, a compilation of 128 ink drawings, colored with watercolours, on different acts of arms from the War of Flanders (75), plans of fortresses and cities (31) and topographic maps (12), all of them accompanied by their corresponding scales, compass roses and detailed legends that illustrate and explain the events represented. The work was presented in 1624 to the Archduchess Elizabeth and is currently preserved in the Royal Library of Belgium under the title Recueil de plans de villes et de châteaux, de fortifications et de batailles, de cartes topographiques et géographiques, se rapportant aux règnes de Charles-Quint, by Philippe II et d'Albert et Isabelle, 1585-1622 .[10]

The detail and precision of these maps and urban views, in addition to their simple but elegant beauty, compare the work of Pierre Lepoivre to that of other illustrious cartographers in the service of the Monarchy Hispanic like Jacob van Deventer and Christian Sgrooten. The choice of the view corresponding to the siege of Mons for our Desperta Ferro Historia Moderna gift #50:The Duke of Alba in Flanders It's not by chance , as it is the most spectacular piece in the collection, a mixture of urban views and cartography, as well as the most detailed visual representation of the Mons site. There is no more valuable graphic document than this collection to verify to what extent the The art of war evolved in the last thirty years of Philip II's reign into a revolution that laid the foundations for modern warfare.

Notes

[1] Van den Heuvel, C.; Roosens, B. (2000):“The Netherlands. The fortifications and the coronation of the defense of the Empire of Carlos V”, in Hernando Sánches, C. J. (coord.):The fortifications of Carlos V . Madrid:Threshold Editions, p. 587.

[2] Villavicencio, L. de. (1567):"Memory of Father Fray Lorenzo de Villavicencio on the consideration that must be taken of what the Duke has to do when he enters Flandes", in Collection of Unpublished Documents for the History of Spain , Vol. 37. Madrid. Widow of Calero, p. 45.

[3] Van den Heuvel, C.; Roosens, B., op. quote ., p. 597.

[4] Pachoto's card points to his Mj. From Antwerp to November 30, 1567, and from another writing to the Duke on January 6, 1568, in Collection of Unpublished Documents for the History of Spain , Vol. 37. Madrid. Widow of Calero, p. 72.

[5] Evelyn, J.; Bédoyère, G. de la (2004):The Diary of John Evelyn . Woodbridge:Boydell Press, p. 40.

[6] Kingra, M. S. (1993):“The Trace Italienne and the Military Revolution During the Eighty Years' War, 1567-1648”, The Journal of Military History, Vol. 57, No. 3, p. 434.

[7] The Duke of Alba to Philip II, Malines, October 2, 1572, in Gachard, M. (ed.) (1851):Correspondance de Philippe II on the affaires of the Pays-Bas , II. Bruxelles-Gand-Leipzig:C. Muquardt, p. 283.

[8] Martens, P. (2014):“Pierre Lepoivre (c.1546-1626):architect, ingenieur, vestingbouwkundige en geograaf”, in Nationaal Biografisch Woordenboek , 21. Brussel:Paleis der Academiën., 657.

[9] Martens, op. quote ., p. 658.

[10] Available online at:[https://opac.kbr.be/Library/doc/SYRACUSE/15357226/recueil-de-plans-de- villes-et-de-chateaux-de-fortifications-et-de-batailles-de-cartes-topographiques?_lg=nl-BE#detail-holdings]