It is often said that the Second World War had a good part of its roots in the end of the First, in the Versailles Treaty of 1919. It is an analysis focused on the harsh conditions imposed on the defeated Germany, but what is not so well known is that Japan also moved away from the West at that time, putting an end four years later to the alliance it had signed with Great Britain to progressively approach what were going to be the Axis powers, something especially noticeable in the army. And one of the reasons was the rejection of the Anglo-Saxon countries to their request to include in the treaty a clause that recognized the racial equality of all peoples.

On November 11, 1918, the Armistice of Compiègne was signed in a railway car, by which a ceasefire was agreed in the Great War and the armies of both sides withdrew to their positions.

It was the culmination of a series of minor armistices, signed individually with some contenders such as Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which in this case added the German Empire and the Allies. The negotiations passed quickly and, after the signature of the contenders, the occupation of the Rhineland was proceeded, putting an end to the conflict.

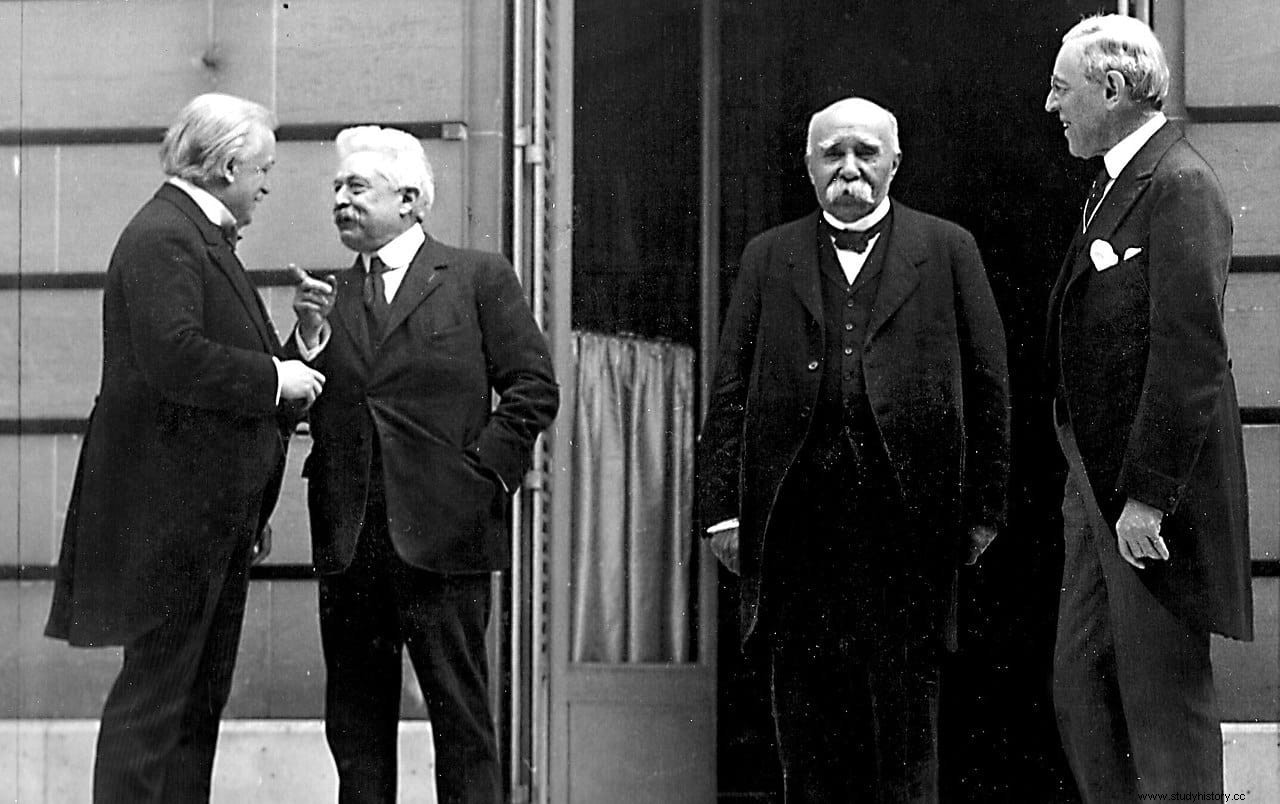

The time had come to negotiate peace, which was carried out at the Paris Conference, which took place between 1919 and 1920 with the participation of thirty-two countries, headed by the political leaders of the so-called Big Four:George Clemenceau for France, David Lloyd George for Great Britain, Vittorio Emmanuele Orlando for Italy and Woodrow Wilson for the USA. Japan, which had also aligned itself with the victors, because since its victory over the Russian Empire in 1905 it was a rising power that also had a bilateral strategic alliance with the British and the government of Hara Takashi advocated a ōbei kyōchō shugi (pro-Western politics), had initially refused to be included in that select group due to his lack of interest in European affairs.

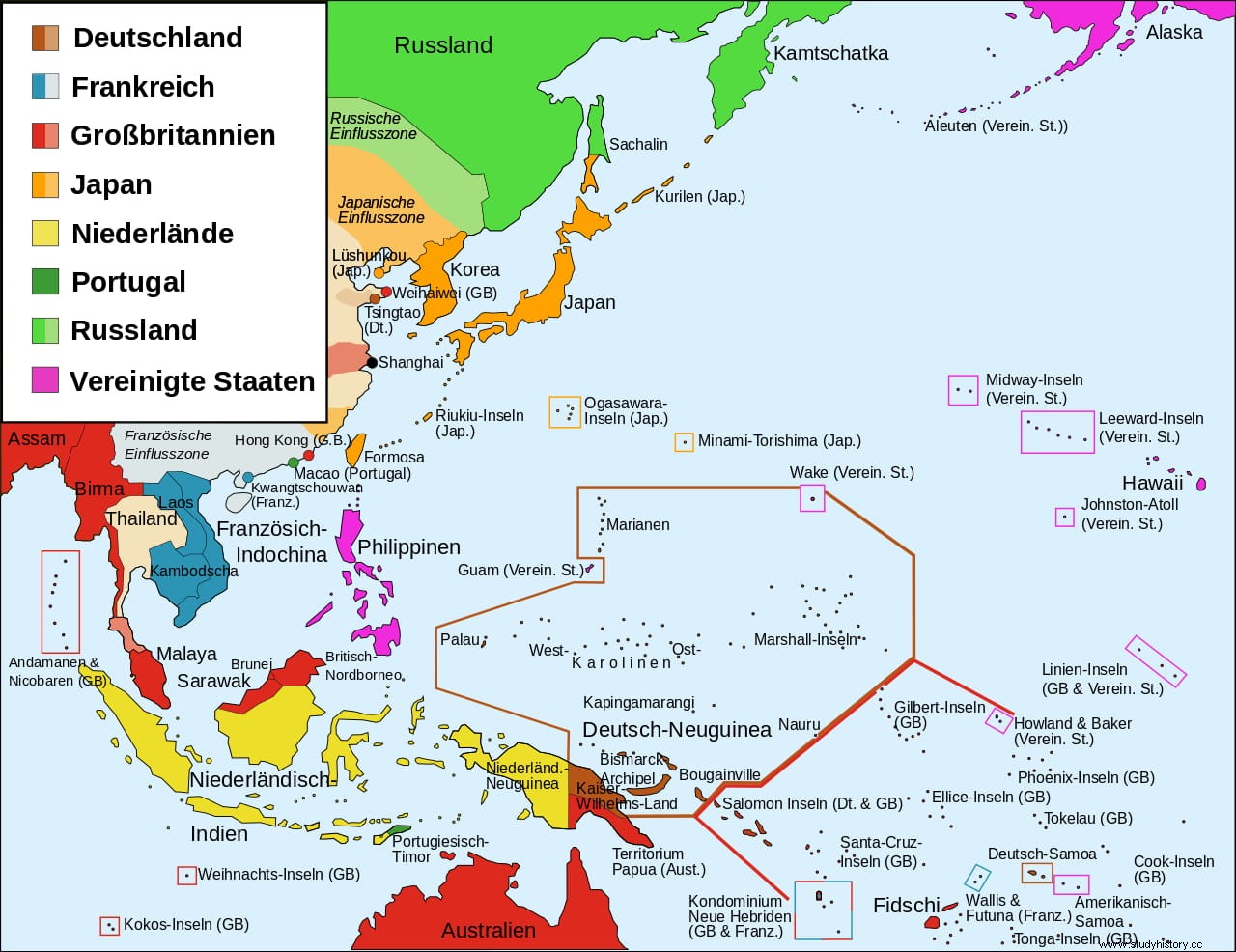

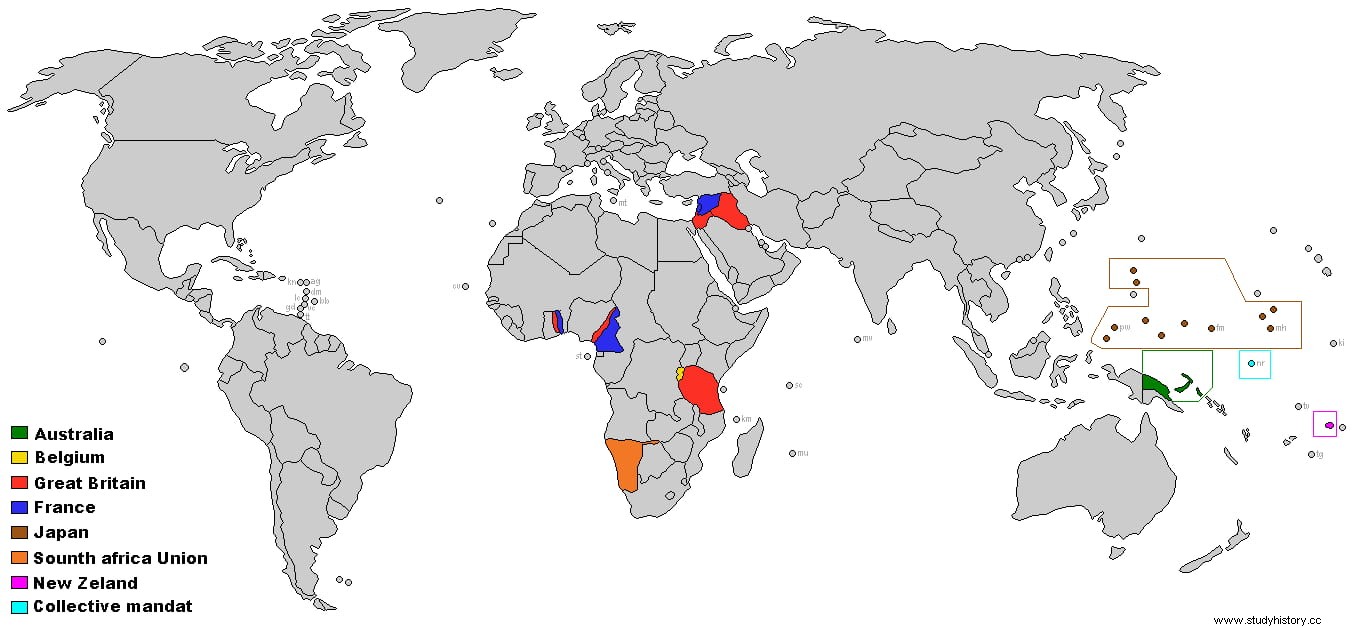

However, the Japanese delegation, made up of former Foreign Minister Makino Nobuaki, former Prime Minister Saionji Kinmochi and Japan's ambassador to London Chinda Sutemi, changed position when the former succeeded the effective second-in-command and aspired to be placed in a place of honor at that long table installed in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles, taking a disappointment when it was relegated to a secondary position. She was only consulted on issues related to Asia and the Pacific, in which her country had direct interests in claiming territories from the former German colonies:Shantung and Kiaochow, on the Chinese coast, plus the Pacific islands north of the equator (Micronesia and the archipelagos of the Carolinas, the Marshalls and the Marianas).

Not only that, but the Japanese became aware of the humiliating comments made by their Western colleagues about them, initially humorous but tinged with racism, such as the one made by Clemenceau about having to be with the ugly Orientals in a city full of blonde beauties. For this reason, when the conference began to discuss the creation of the League of Nations, an international organization that would regulate international relations by exercising arbitration on problems and thus avoiding the risk of a new world war, the Japanese delegation proposed the inclusion of a clause that recognized “the principle of equality of all countries and the fair treatment of their nationals” .

The League of Nations project was based on one of the Fourteen Points enunciated by Woodrow Wilson in 1918 to create new war objectives that would be morally defensible for the Triple Entente, while at the same time serving as a basis for negotiating with the Central Powers . In fact, the explanatory memorandum of the Pact by the League of Nations said verbatim:

The Jinshutekisabetsu teppai teian (Proposal to Abolish Racial Discrimination) made by the Japanese, did not intend to go into details but to be a general statement and read as follows:

Makino Nobuaki (who was the de facto head of his delegation due to Saionji Kinmochi being seriously ill) argued this by referring to the fact that soldiers of different races had fought together on the same side, although obviously the real reason for that initiative it was geostrategic:to prevent his country from being assigned an inferior status that would harm it in the future international order. In fact, Japan itself maintained a discriminatory policy towards Chinese and Koreans, for example (in Korea, the March First or Samil Movement against the Japanese occupation had been harshly repressed, with thousands of deaths, that same year 1919).

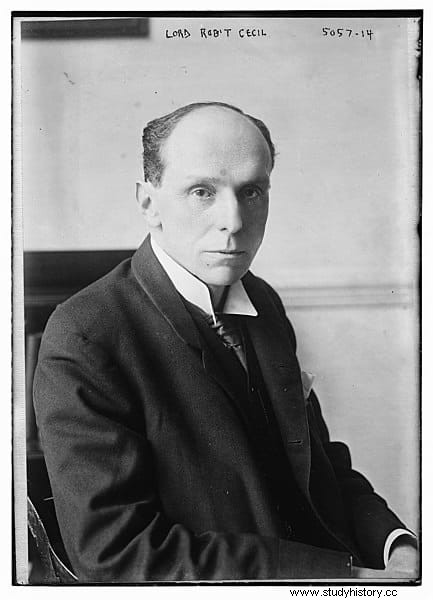

The real problem of Jinshutekisabetsu teppai teian It was that, without intending to, it questioned the foundations of colonialism and with it the external functioning of the great powers, as demonstrated by the fact that other countries adhered to the proposal. Therefore, the British Robert Cecil, who took the floor after Nobuaki, warned that perhaps it would be better not to deal with such a controversial issue. He was supported by the Greek Eleftherios Venizelos, who also wanted to eliminate the clause that prohibited religious discrimination, being immediately answered by a Portuguese diplomat who claimed he had never signed a treaty that did not mention God.

To avoid these discussions, Cecil (future Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1937), discarded the prohibitions of discrimination, both racial and religious, from the document. Now, in reality, it was a very topical issue because the Anglo-Saxon countries (USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) were immersed in a policy of restricting oriental immigration that the Japanese described as « shame» , to the point that others affected such as the Chinese, with whom they were bitterly at odds as both coveted the former German colonies of Tsingtao and Shandong, supported Nobuaki's anti-discrimination clause.

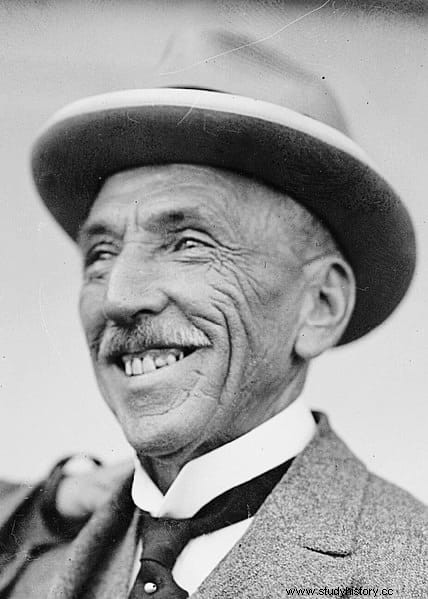

The truth is that the racial question was not based only on genetic causes but also economic ones. The Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, rejected equality because he came from the trade union world, which in the Anglo-Saxon sphere was opposed to the entry of Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Polynesian immigrants because they accepted minimal wages, hence he aligned himself with the policy of White Australia (which, based on the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, gave preference to British immigrants over others until 1949) and even joined in the racist jokes.

Opinions were divided. New Zealand Prime Minister William Massey also took a position against the clause and Britain's Arthur James Balfour declared that he did not believe that « a man from central Africa was created equal to a European» , putting the government of Lloyd George in a compromise because both the alliance that Great Britain had with Japan since 1902 and the union of the British Empire would falter if it disavowed the immigration exclusion policy of Australia and New Zealand.

The prime ministers of South Africa and Canada, Jan Smuts and Robert Borden, tried to mediate between the Japanese and Hughes, summoning them to a meeting to bring their positions closer together. It was a disaster. The former could not hide their displeasure at someone whom they considered a simple and coarse peasant, and he came to agree with them by complaining that they were bowing all the time. However, he agreed to admit the clause if emigration was excluded from it... which the Japanese refused to accept.

The opinion of the United States was yet to be known, although it was not difficult to imagine. Woodrow Wilson was a convinced segregationist that in addition to seeing the immigration policy in danger, which restricted the access of Asians to the west coast of the United States, he needed the votes of white supremacists -fundamentally Southern Democrats- for the Senate to approve the entry into the League of Nations. Likewise, he had Great Britain as an ally and did not want to lose her, since a good part of his collaborators were WASP ( White Anglo-Saxon Protestant ie white Anglo-Saxon Protestants), Australia's opposition to the Japanese proposal suited him like a glove.

That is why it was he who starred in one of the most tense moments of those days, that of the final vote. It took place on April 19, 1919, after the arguments of each representative. Seventeen delegates voted, eleven of whom voted in favor of including the Jinshutekisabetsu teppai teian (Japan, France, Italy, Brazil, China, Greece, Serbia and Czechoslovakia), compared to the abstentions of the others (British Empire, USA, Portugal and Romania) and the non-appearance of Belgium. In other words, no one voted against it, despite which Wilson decided to annul the process due to the manifest opposition , considering that there should be unanimity.

In exchange, the US president promised the Japanese to support their territorial claims over the German colonies in China and to ratify their administration, on behalf of the League of Nations, over those of the Pacific archipelagos that they had occupied in 1914, as it would happen. . It was not enough to satisfy the Japanese, who aspired to a full annexation, so they ended up leaving Paris. This did not have an immediate effect, since the conference had come to an end and the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, but it did in the medium term.

And it is that Japanese public opinion began to distill anti-Americanism, especially evident in its armed forces after, in 1922, the Washington Treaty imposed on the Imperial Navy a limit of units below that assigned to the Royal Navy and the fleet of USA. Anglophilia was abandoned in favor of a Germanophilia that had already permeated the army during the First World War and, in a few years, military bases were installed on those islands ceded by the League of Nations, which now came to be governed directly. because Tokyo announced in 1933 that it was leaving said body. He did it together with Nazi Germany (Italy imitated them in 1936), at the mercy of sympathetic prime ministers such as Fuminaro Konoe or Hideki Tōjō.

Meanwhile, the United States was shaken that same 1919 by what became known as Red Summer (Red Summer), riots between white and black citizens that devastated some thirty US cities. Wilson didn't get the play right; Although he won the Nobel Peace Prize that year, he suffered a stroke that left him a hemiplegic and could not adequately defend his position, so the Southern Democrats voted against entering the League of Nations. This gave rise to the paradox that its main promoter would not be part of it, leading it to a failure that was tragically reflected in its ineffectiveness in the face of the Spanish Civil War and the immediate Second World War.