When I visited Orkney years ago, one of the things I had in mind was to see Scapa Flow Bay up close. It is a place that has the desolate tranquility typical of the small archipelago where it is located, almost always with the light filtered by the same overcast sky that usually produces several daily rains. Taking a look at its gray waters, strangely placid as they are protected by dikes built by Churchill, nobody would say that there was a time when it was one of the largest underwater cemeteries in the world, with more than fifty sunken ships on its bottom. . Most were part of the Hochseeflotte (High Seas Fleet) of the German Empire, interned there at the end of World War I but whose crews scuttled them to prevent them from being divided among the victors.

On November 11, 1918, the armistice was signed in the French town of Compiègne, ending four years of bloody global conflict. The terms of the deal called for the unconditional handover of the German U-boat fleet to the Allies, but determining what to do with the surface ships was another story. They were the result of the naval construction project that since 1898 was directed by the Secretary of the Navy, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, with the aim of guaranteeing the integrity of the colonial empire and expanding it, as well as achieving numerical and technical superiority over the Royal Navy. The latter did not succeed because the British, to counteract it, also launched to expand their own fleet.

That arms race led to war in 1914 and although one of its first battles, that of Jutland, ended in a draw, the truth is that it benefited His Graceful Majesty more by sending a good part of the Hochseeflotte to dry dock for the rest of the conflict. , shifting the limelight to submarines and corsairs. Once the hostilities were over and given that the neutral Norway and Spain rejected the proposal to welcome the German units in their ports, Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss suggested interning them in Scapa Flow, maintained by the minimum German personnel and under the custody of the Grand Fleet, the great British fleet resulting from the merger between the Home Fleet and the First Fleet, which was based precisely in that corner of northern Scotland and led by Admiral David Beatty.

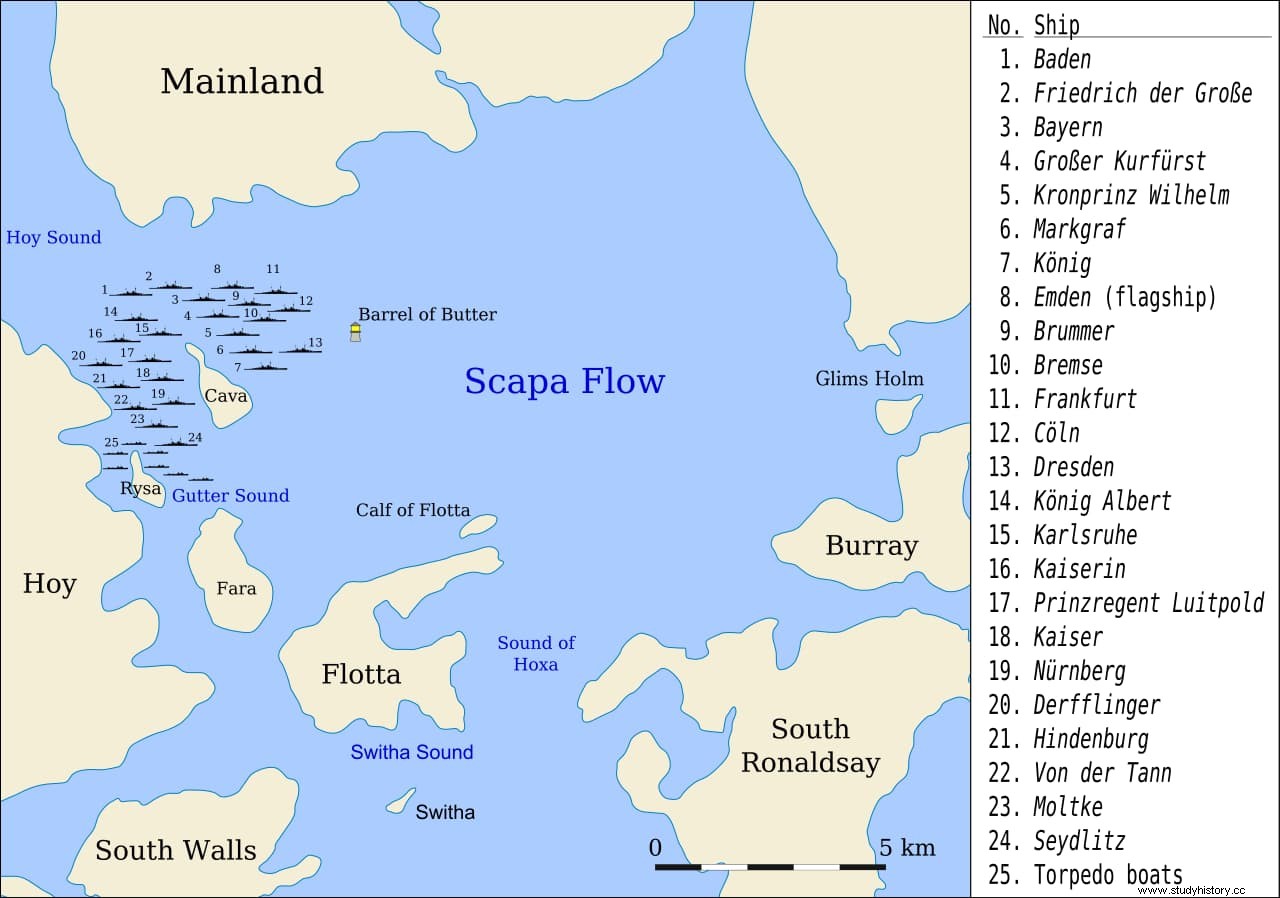

As the one hundred and seventy-six active submarines assembled in Harwich, the seventy ships of the Hochseeflotte, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, set sail for the Firth of Forth, in the estuary of the Scottish river of the same name, where the Great British Fleet -reinforced by those of its allies- to escort them to Orkney. They arrived at the end of November and, once their guns were disabled, they were distributed around the place according to their size:the battleships and cruisers anchored to the north and west of Cava, an uninhabited island of barely one hundred and seven hectares, while the destroyers did so in Gutter Sound, between said island, that of Fara and that of Hoy.

The operation was not easy for the Germans, as some ships -such as the battleship SMS Köenig and the SMS Dresden cruise ship – they had problems with their machines and could not keep up with the others; above, a destroyer sank when hitting a mine. Therefore, initially there were seventy units there, although later the two delayed ones and another couple more arrived. These were not the only difficulties to overcome, since from 1917 the Hochseeflotte crews had begun to show signs of dissatisfaction with the eternalization of the war, crystallizing first in the form of small acts of passive resistance (hunger strikes, refusing to work…) and then in open protests and anti-war demonstrations.

Courts-martial sentenced nine sailors to death (although only two were executed) while imprisoning dozens more, but that did not stop the movement, which blossomed on November 3, 1918. That day, when ordered to set sail for the English Channel for a battle against the Royal Navy in a war that was already known to be lost, the crews of the SMS Thüringen and SMS Helgoland , supported by the trade unions and the USPD (Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany) of Kiel, staged the riot of the same name, seizing that city. That spelled the fall of the regime and the end of the war, but the sailors appointed to guard the German ships at Scapa Flow - two hundred apiece, officers included - were in no better mood.

Indeed, the food was bad, they were cut off from the rest of the world, and they spent the day with nothing to do, which inevitably had an impact on discipline. It got to such a degree that they organized themselves into committees, which had to approve the orders given to them by the officers; one of them called himself the Red Guard and was clearly unwilling to obey. The men, in short, were as abandoned as their ships. They had a medical service but no dentist, they received mail very late - always with censorship - and they could neither go ashore nor transfer to other ships. This being the case, it is not surprising that it was decided to progressively repatriate the number of German sailors from Scapa Flow, so that the initial twenty thousand were reduced to less than five thousand and the figure continued to drop.

And while they languished in that remote place for seven months, the Allied powers continued to argue, not only with the Germans but with each other, each demanding to keep a number of ships to reinforce their respective navies. Of course, Ludwig von Reuter's intention from the outset was to prevent it, ignoring an armistice clause that prohibited sinking ships, but he preferred to wait for the outcome of the negotiations, perhaps waiting for a restrictive order from his own government. However, rumors began to circulate about the leonine conditions that were to be imposed on Germany in the final treaty, scheduled to be signed at Versailles on June 21, 1919, and the German admiral took the drastic decision to sink the Hochseeflotte.

It cannot be said that his guardians did not expect him because he was within the expected and they had also heard something about it among the Teutonic sailors. In fact, the British Admiral Sydney Fremantle, who was in command of Scapa Flow, submitted to his superiors a plan to take direct control of the German ships on the night of the 21st, as soon as the treaty was signed. But he was informed that the signing was going to be delayed for two days, so he considered that there was no rush and instead took advantage of the good weather to carry out an anti-torpedo exercise, leaving only three destroyers and a few armed fishing boats in Scapa Flow. He scheduled the occupation of the German ships for the 23rd; he wouldn't give him time.

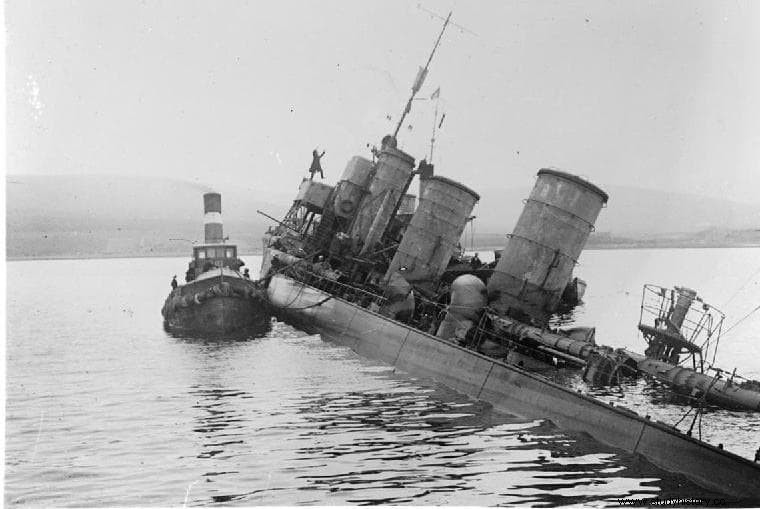

At mid-morning on June 21 and using signal flags, von Reuter gave the order to scuttle the ships. German sailors opened the spigots and portholes of their ships; in some, holes were even made in the bulkheads to speed up the process. For half an hour the British did not notice anything anomalous, but around twelve o'clock they noticed that the battleship SMS Friedrich der Grosse list to port and that all the crews boarded the boats, leaving their flags hoisted. Fremantle was quickly alerted and sent back to Orkney at full speed. But it was late; It arrived two and a half hours later, when most of the ships had already gone to the bottom.

Basically, only the important ones were still afloat due to their size and he set out to save them. To do this, he ordered his men to climb up and run them aground. However, the operation only went well with eighteen destroyers and three light cruisers; Of the big ones, only the battleship SMS Baden was saved. , adding a total of twenty. The rest, more than fifty, remained under the waters of the bay, the last to be lost was the SMS Hindenburg cruise ship. , at five in the afternoon. Nine sailors died with them - including the captain of the battleship SMS Markgraf -, shot by the British when they tried to prevent them from boarding. The other men, less than two thousand, no longer made sense to keep them there and they were transferred to the Invergordon naval base, near Inverness, from where they were transferred to the prison camp of Nigg (Aberdeen).

Ludwig von Reuter was taken with his officers to HMS Revenge , where Fremantle harshly reproached him for his violation of the armistice conditions, to which the Teuton replied that «any British officer would have acted in the same way» . Indeed, in Germany they considered him a hero, something that did not prevent him from spending time as a prisoner of war with his men. Of course, they were soon repatriated while he had to remain on British soil until the end of January 1920. Five months after returning to his country, following the terms of the Treaty of Versailles that ordered a drastic reduction in the navy, he was asked to resignation; he would go to the Council of State and, already in Nazi times, he was promoted to admiral, dying in the middle of World War II of a heart attack.

Despite everything, the British viewed with some relief this disaster that deprived their allies of reinforcements for their fleets and guaranteed the prevalence of the Royal Navy's superiority on the seas. Even so, the stranded ships were divided up, leaving the others where they were because refloating them was expensive and unnecessary; If there was anything left over after the war, it was scrap metal. Only four destroyers whose location threatened local shipping were brought to the surface. In the mid-1920s, a businessman bought the remaining twenty-six destroyers, refloating twenty-four, and then going on to do the same with five battleships and two cruisers. He then sold the rights to a company that salvaged a few more large ships.

They all went to scrap, logically, later becoming one of the world's main sources of low-grade steel (manufactured before the nuclear age). The irony is that part of that metal was bought by Germany and would be used to build the Kriegsmarine submarines that would fight in World War II. In October 1939, one of them, Major Günther Prienn's U-47, entered Scapa Flow, bypassing the defenses, and torpedoed the battleship HMS Royal Oak. , which also went to the bottom dragging more than eight hundred sailors. She rests there today, next to the seven German wrecks that were not raised because they were deeper (up to forty-seven meters) and, therefore, required greater technical difficulty.

For a time, loose pieces were removed, but since 1979 they have been protected as monuments and archaeological areas... which has not prevented three of them very close to each other, the Markgraf , the König and the Kronprinz Wilhelm , were sold by eBay in 2019; the Karlsruhe it had been auctioned before.