In early December 1943, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Armored Brigade began the most savage battle of the Italian Campaign. In the mud and rain, the troops attacked from the Moro River to Ortona. Then house by house and room by room a fierce battle was waged against the determined German defenders. With extraordinary courage, the Canadians won and secured the city just after Christmas . So reads a plaque placed in the year 2000 in the piazza Plebiscite in the town of Ortona (Italy), where at the end of 1943 one of the fiercest battles of World War II took place, despite its modest size.

Ortona is a municipality in the province of Chieti, in the Los Abruzzo region. It overlooks the Adriatic Sea, some twenty kilometers south of Pescara, and has a rich history:founded in ancient times, probably by the Frentani (an Italic people descended from the Samnites), incorporated into the Roman domains and occupied in the Medieval by the Franks first and the Normans later, it was conquered by the Republic of Venice -which disputed it with Aragon- in the 15th century, to pass into Spanish hands in the next and finally join the Kingdom of Italy in the 19th century.

Today it is a very small city that multiplies its population in summer but that out of season barely exceeds twenty thousand inhabitants, double the number it had when the Second World War passed its halfway point and entered the Italian Campaign in mid-1943 with the objective of forcing the Germans to divert troops from France, since Operation Overlord, the famous landing in Normandy, was already being planned. Since the North African Campaign had just ended successfully, the Italian peninsula seemed like the next logical step to put pressure on the Axis on several fronts.

Sicily was the first step and when the operations jumped to the mainland, in the operationsAvalanche , Baytown and Slapstick , the Italian regime collapsed. In July, Mussolini was dismissed by order of King Victor Emmanuel III, who then signed an armistice with the Allies. But a month and a half later, a Waffen SS commando released the Duce , who went on to preside over an Italian Social Republic; In reality, beyond his headquarters in the Alpine region of Saló, he lacked effective power against the Wehrmacht, which was the one that took control of the country de facto and set out to stop the Allies.

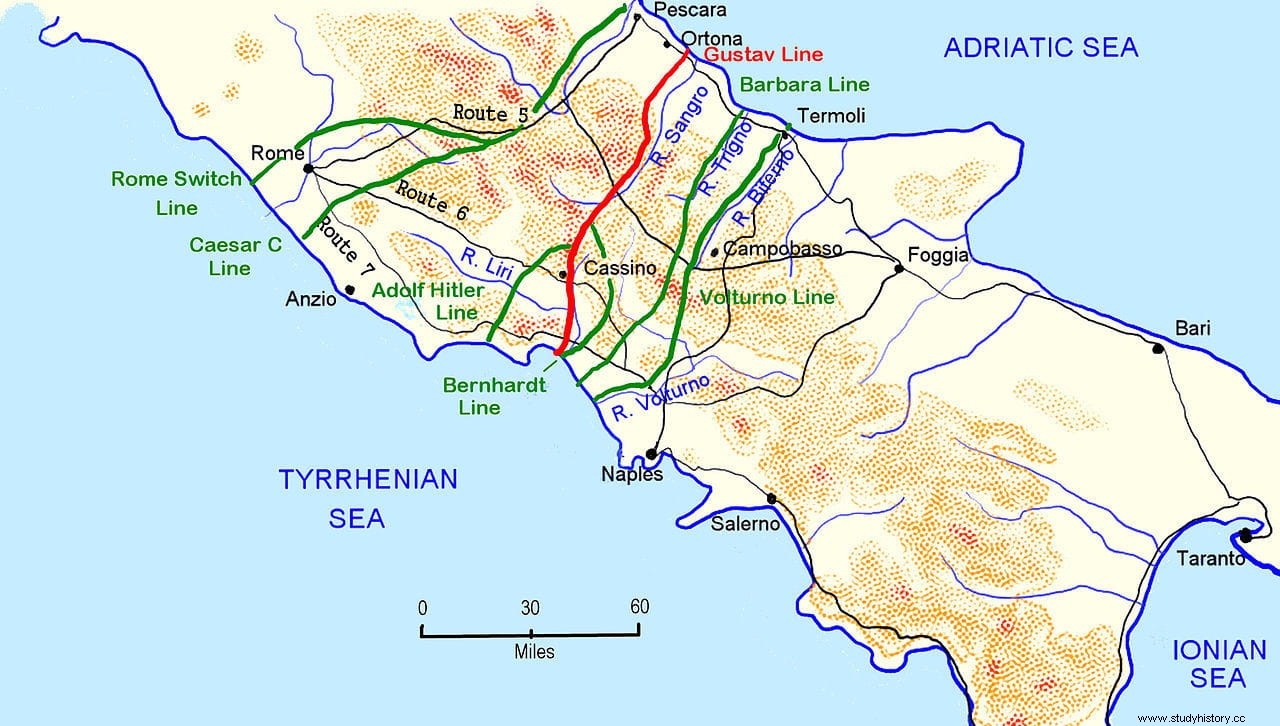

Their advance along the peninsula to the north - Americans on the west coast, British on the east - was not easy because the Germans took advantage of the difficult orography to take up positions. Thus, both the Apennines and the Abruzzo were authentic natural barriers that favored the creation of a set of defensive lines that extended from coast to coast through the central peninsular area, between the Tyrrhenian and the Adriatic:from south to north the Volturno , the Barbara , theGustav , the Caesar and the Switch (in the north more were established).

There were two smaller ones, the Bernhardt (or Reinhard ) and the Hitler (renamed Senger in 1944), the first being the scene of the famous Battle of Montecassino, but both were complements to the western part of the Gustav , whose eastern end ended precisely in Ortona, taking advantage of another obstacle provided by nature, the Sangro River, which ran parallel in that section. Between the three they formed the so-called Winter Line , armed with bunkers, cannons, machine gun nests, barbed wire and minefields.

Added to this was Army Group C, a group of troops commanded by Hessian General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, who had taken part in the invasions of Poland, Greece, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, and to which Italy was assigned that summer from his command in France. Under the orders of Marshal Albert Kesserling, commander of the German forces in Italian territory, he was ordered to delay the advance of the enemy as much as possible. To defend the eastern part of the line he appointed Richard Heidrich, a paratrooper general who had fought in Poland, Crete, and the siege of Leningrad.

Heidrich would make a name for himself above all for Montecassino, but first he had to face Major General Christopher Vokes in Ortona, an officer from an Irish family with a military tradition (although he emigrated to Canada with his parents as a child) who had just been promoted. to relieve his superior in command of the Canadian 1st Infantry Division, due to his illness. Vokes came from the General Staff, where he had a brilliant career, and he was valued for the balance he achieved between the technical part (operational planning and direction) and the human part (understanding and motivation towards his men).

The Volturno lines and Barbara fell throughout the month of October-early November 1943. The offensive against the Gustav , led by the British Eighth Army (made up of four infantry divisions, one British, one Canadian, one Indian and one New Zealand, plus two armored brigades) and jointly led by General Sir Harold Alexander, began on 23 November. Before the month was out, Major General Vyvyan Evelegh's 78th Infantry Division had successfully crossed the Sangro, so the next objective was another minor riverbed, the Moro, four miles away. It was at this point that Evelegh, who had suffered seven thousand casualties in six months, handed over the baton to Vokes.

The attack resumed on December 5 and, according to the plan drawn up by Montgomery, Ortona and Pescara were to be taken on the coast (the latter considered the best way to Rome), while the objective of the New Zealanders, a little further inland, was Orsogna; the Indians had to remain on the lookout, as support. Opposing them were the 1st Parachute Division, the 90th Panzergrenadierdivision , the 26th Panzerdivision and the 65th Infantry, supported by smaller units and by the LXXVI Panzer Corps. Vokes managed to reach the Moro on December 9, but was then stopped, as were the New Zealanders, which is why the Indian division was ordered to intervene, whose engineers built a bridge.

However, the panzergrenadier s, who had orders to "fight to the last house and tree" , resisted by receiving reinforcements from the paratroopers (among whom was Lieutenant Harold Quandt, son of Magda Goebbels's first marriage, who would also fight in Montecassino). Meanwhile, on December 23 Montgomery left Italy to focus on Operation Overlord - being replaced by Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese - Brigadier Howard Graham, of the 1st Infantry Brigade of the 1st Canadian Division managed to overcome the inclemencies meteorological (the rains turned the land into a quagmire) and reach the outskirts of Ortona. There he was relieved by Brigadier Bert Hoffmeister, of the 2nd Brigade, to carry out the assault.

It was not going to be easy, since the veteran Teutonic engineers and paratroopers had demolished much of the old town to barricade the narrow streets, where they could place their machine guns, hide their tanks and lay mines or other booby traps. A deadly labyrinth that would force the Canadians to fight in a somewhat atypical way.

It all started on the 20th, with the frontal attack of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment and the Seafort Highlanders of Canada , to which the 3rd Infantry Brigade joined with a flanking movement. The next day they entered the inner city, but there awaited them an inferno that is often described as a version of Stalingrad on a smaller scale.

And it is that, although the Allies were aided by the tanks of the 12 e Armored Regiment of Canada , the Germans had hidden anti-tank guns that slowed them down, forcing the troops to fight house to house and apply an unusual urban warfare tactic in which, foregoing street fighting, soldiers had to open holes in the walls to access the buildings and, moving from room to room, dislodge the defenders. It was what was baptized as mouse-holing (mousetrap), which had already been practiced in Dublin during the Easter Rising of 1916.

Thus, the Canadians used their PIATs (anti-tank weapons) to make those openings and throw grenades inside, and then enter and sweep the rooms and stairs with machine gun fire (even reaching melee). Often they had to repeat the operation with the partitions, passing to the adjoining rooms, as the British did against the Zulu in Rorke's Drift, although in this case it was to escape. Likewise, it was a way of moving from one building to another without being exposed to a burst or a sniper shot in the open air. There was no shortage of occasions when the entire house was dynamited so that it collapsed on the enemy, something that was practiced by both sides.

On December 24 and 26, the Germans carried out counterattacks that caused a significant number of casualties to the Canadian forces in the city -some six and a half hundred-, but being short of supplies and in danger of being overwhelmed by flank and pocketed by the 3rd Brigade, the defenders judged it preferable to leave Ortona the following day. Therefore, Vokes seized the city after little more than a week of battle, on December 28, although at the cost of human and material bleeding.

The historic center of Ortones was practically destroyed and the cathedral, the hospital and some other places were barely saved, thanks to the fact that the march of the Teutons made its planned destruction unnecessary. However, the worst was the human cost of what became known as Bloody December .

The Canadians recorded a total number of casualties that exceeded five hundred dead - one thousand three hundred and seventy-five, if the previous actions in the Moro River are counted - and nine hundred and sixty-four wounded, which meant a quarter of the casualties suffered by them. throughout the Italian campaign, to which must be added nearly five thousand evacuated due to illness and/or exhaustion. It seems that Vokes cried when he heard those figures, which did not prevent his men from nicknamed him the Butcher and that he received harsh criticism for his unimaginative system of sacrificing battalion after battalion (which he would continue to do in the continuation of the march towards Pescara).

And all for what, many wondered. The impact that the battle had on the course of the war was not very important, compared to other more renowned ones, except for the fact that the Germans took good note of their tactics and repeated them at Montecassino. In fact, the analyzes on Ortona's strategic value differ quite a bit depending on the side. The Allies, for example, considered it valuable as one of the few usable deep-water ports on the Adriatic to supply the Eighth Army, shortening existing supply lines at the time, which stretched as far as Bari and Taranto.

For the Germans, on the other hand, its value was limited because the port facilities had been blown up and could not be used, so it was not worth the bloodshed involved. In addition, they always considered Ortona a minor confrontation -two battalions on each side- that they defended to fulfill their duty and amplified by the Allies; Vokes seemed to express this with the petulant declaration that he had crushed and taught the adversary a lesson, forgetting that he had inflicted many more casualties on him than he had received.

In any case, with greater or lesser reason, but due to its resemblance to the development of what happened, fighting house by house, the battle has gone down in history with the nickname of Stalingrad of Italy .