If someone thinks that the tricksters of esotericism are a product of our time, they are completely wrong. Quackery is as old as speech and history is full of impostors, storytellers and frauds:there have always been false and enlightened prophets who take advantage of their talk to do business. One of the oldest documented examples is that of Alexander of Abonutico, a Greek oracle who lived in the 2nd century AD. and a mystery cult was invented to a serpent god named Glycon who was a puppet controlled by himself.

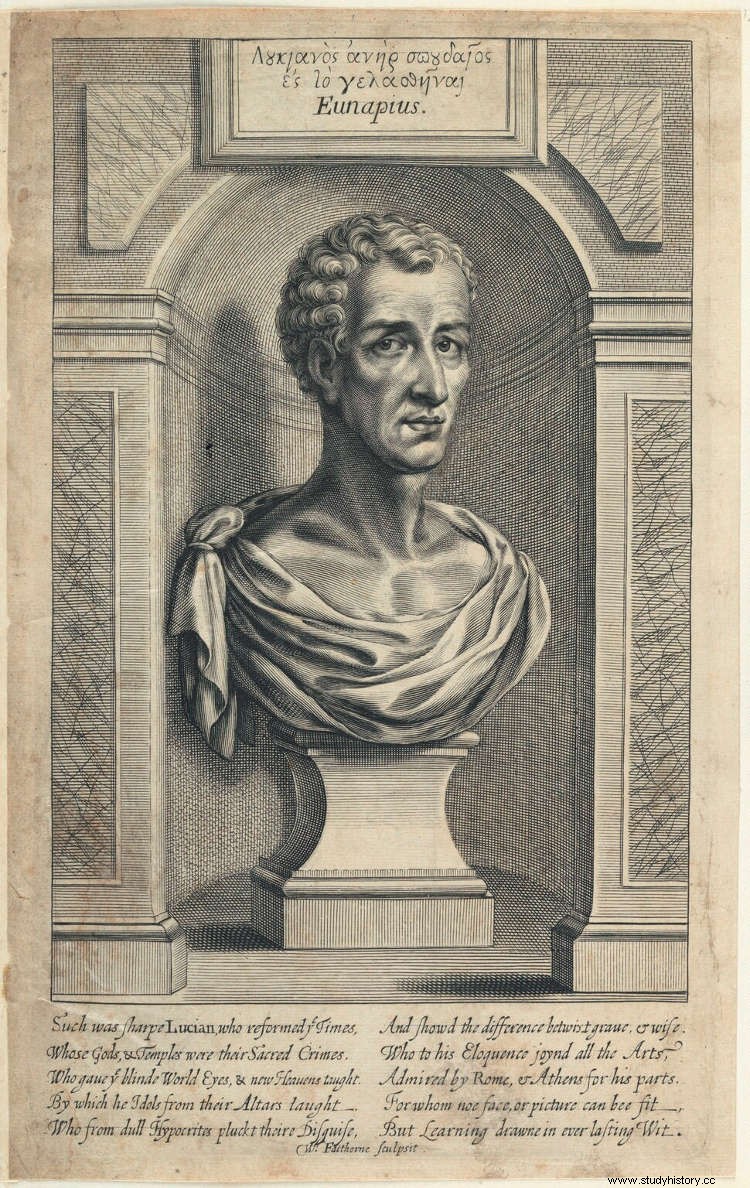

As is often the case, there is little reliable information about Alexander's youth and life before he became famous, except that he was born around 105 AD. in Abonautico. This was a city located in Paflagonia, an area in north-central Anatolia, overlooking the Black Sea between Bithynia and Pontus, in present-day Turkey, then dotted with Hellenic cities. The main documentary source on this character has been left by Lucian of Samosata, a writer also Greek, a native of the homonymous Syrian region, who was a contemporary of his and whose opinion was not exactly favourable; suffice it to note that the title of the work where the subject is treated is Alexandrum et pseudo prophet (Alexander or the false prophet ).

In fact, for a time it was considered that this text was creative, that is, a fiction. Only the reference in this regard by another author, the Christian philosopher Athenagoras, to a statue of Alexander erected in the forum of the city of Paros (on the Cycladic island of the same name), plus the discovery of archaeological evidence, mainly coins, have shown that it was someone real. And, therefore, Luciano's story acquires the value of a chronicle, even when it is a sharply critical piece that reveals that perhaps it went a little further. Why? Because Alejandro maintained a strong confrontation with Epicureanism and Luciano, on the other hand, was a declared admirer of that current that at the end of his pamphlet includes an ode to Epicurean.

In any case, his is the only testimony that exists, so there is no choice but to follow him. We said that we know little about Alejandro de Abonutico prior to the events. Only that he acquired knowledge of medicine as a disciple of a doctor who, according to Luciano, was also a fraud; Perhaps it was Apollonius of Tyana, a neopythagorean sage from Cappadocia, a follower of Aesculapius, as well as an ascetic and famous for being a miracle worker, which caused him to be accused of practicing magic and having to go into exile by order of Domitian, who he saw him as dangerously close to Christianity. At the end of the formative stage, Alexander began to practice medicine accompanied by a Byzantine associate (from the colony of Byzantium, not Constantinople) of whom only his name is known, Cocconas; with him he made a crucial visit to Pella, the Macedonian capital.

He then returned to his hometown around 150 AD. to found an oracle of Aesculapius (Latinization of Asclepios, the Greek divinity of medicine). The project was ambitious but he managed to carry it out after burying some tablets with a prophecy according to which the son of Apollo would be born again and he would do so in a snake egg. Alexander assured that the exact place was the foundations of the temple that at that time was being built precisely to Aesculapius (whose symbol was a snake coiled around a rod) and made sure to place an ophidian egg there to give a blow of effect. He was probably well versed in human psychology, as tricksters often are, and the people of Paphlagonia were known to be especially gullible.

So, in a very short time, Alexander of Abonutico had managed to organize a religious cult to this reborn god, whom he named Glycon. He personally took charge of spreading the good news by appearing in the markets with a hollow goose egg where he had placed a small snake. At one point during his speech, he opened it showing its content and thus amazed the audience. Taking advantage of his rhetorical ability, personal attractiveness, charisma and undoubted gifts of intelligence, in less than a week people were convinced and approached the sanctuary, where the animal had already been replaced by another larger one:a domesticated snake that was a blond horsehair wig had been placed around the head to give it a human appearance, forming a theriomorphic being which, being alive and moving, made a deep impression on those who saw it; from a distance, yes, which prevented discovering the trick.

The truth is that the cult of these reptiles was not new in the Hellenic world, since the Macedonians had been practicing it for a long time -remember that Alexander and his companion Cocconas were in Pella- as a survival of ancient fertility rites and their mythology It altered the classical Greek a bit in that sense:in it, Zeus disguised himself as a snake to impregnate Olympias so that she would give birth to Alexander the Great (she had married Philip as part of a mystery rite in Cabeiri, on the island of Samothrace, where pre-Hellenic gods were worshipped). It is not surprising that a multitude of sterile women visited the place with votive offerings to ask the god to fix his problem; other people joined them in search of protection against the plague.

Likewise, there were those who came in search of answers to questions about their lives, businesses, loves and the like, but above all with illnesses; after all, it was a shrine to Aesculapius. Alexander attended them seated on the altar with the snake coiled around his body and responded in the usual oracular way:confused and ambiguous, which only increased the enigmatic tone of the farce. He did not raise suspicions because there was a whole setup around him that included false questions in sealed envelopes that he himself had prepared in advance, as well as a whole series of tricks:he soaped his mouth to simulate trances, he said phrases mixing Hebrew and Phoenician as if new language was involved and sometimes he replaced his snake with a puppet that he managed half in the dark while an accomplice spoke through a tube connected to the puppet, startling the unwary. According to Luciano, more wonders were told:

It is believed that he made tens of thousands of oracles, which, as he charged them at the modest price of a drachma with two obols (the obol was worth one-sixth of a drachma), made him rich in a short time. But his prosperity was not due exclusively to that. We have already said that he had the typical cunning of the rogue and wrapped his business with a mysterious and initiatory air in the style of the one in Eleusis, a city located thirty kilometers from Athens where Demeter, the goddess of agriculture and fertility, was worshiped. that taught Man the agrarian cycles. And in the same way that those Eleusinian mysteries transcended beyond Greece, the fame of that version with Glycon did the same for Anatolia and Thrace, reaching Rome and becoming fashionable among the endless other types of faith that took root there.

This allowed Alexander of Abonutico to become related to the Roman upper class through the marriage of his daughter to Publio Mummio Sisenna Rutiliano, a former consul who at that time held the position of proconsular governor of the province of Asia. Rutiliano was quite gullible, the type of person who thinks he sees a sign in anything, according to Luciano:

Rutiliano fell squarely into the net by naively asking the oracle for advice on whom to marry and Alexander answered that with his daughter, whom he would have fathered with nothing less than the goddess Selene; It didn't matter that she was a girl and the marriageable was in his sixties. Apparently Luciano was a friend of the Roman and tried to dissuade him but Rutiliano was so stubborn that he didn't listen to anyone. The chronicler's animosity was twofold, since Alexander had prohibited Epicureans and Christians from accessing the sanctuary due to their strong criticism. That position worsened even more when he, on top of him, he ordered to assassinate him during his return trip by ship. It was the year 159 AD. and Luciano was able to avoid the assassins by embarking on another ship, but as soon as he reached port he filed a complaint with the imperial governor Lucio Hedio Rufo Lolliano Avito.

However, Lolliano was uncooperative in the face of the difficulty of proving the accusation and the idea of confronting not only someone whose popularity stretched almost from one end of the Mediterranean to the other, but also his son-in-law, a colleague from the magistracy who also had a great power and would surely intervene so that everything would come to nothing. Indeed, Luciano had to give up and the oracle's fame continued to grow. It reached its zenith in 166, during the so-called Antonine Plague, a pandemic (smallpox according to some authors, measles according to others) introduced by the eastern legions the previous year and that affected a good part of the empire, even causing the death of the Emperor Lucio Vero among thousands of other victims. The oracle dictated by Alexander was used as a protection amulet against contagion and was hung on the doors of houses.

This reached the ears of the new emperor, Marcus Aurelius, who also commissioned his, although on another matter:the future of the campaign that he was about to launch on the Danube against the Marcomanni (a confederation of Germanic peoples who inhabited approximately what is now Bohemia, in the Czech Republic). Alexander replied that he would achieve victory if he threw two live lions into the river. This was done but it did not work and the Romans reaped a defeat that forced the oracle to give an explanation, twisting the original meaning of what was prophesied according to the model of what was done at Delphi when Crassus had asked for an opinion before facing the Parthians .

However, making good that aphorism that they speak of one even if it is bad, that the emperor himself had consulted him allowed Alexander of Abonutico to settle in Rome, where he not only practiced divination but even arranged for his hometown to be renamed Ionópolis (City of the Serpent). In that period oracles arose in many corners of the empire but Alexander's would prove short-lived, barely lasting seven years and quickly dissolving when gangrene in the leg killed his creator in 170 AD. It was then that it was discovered that he would not stay young until he was killed by lightning at the age of one hundred and fifty, as he had claimed:he not only died in his seventies but also wore a toupee.