If we ask for the names of historians of Ancient Rome, surely Titus Livy, Plutarch, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Dio Cassius, Polybius will come out... Most of them have in common being of Greek origin, although some were Roman and others obtained citizenship, but there is one thing on which they unanimously agree:having used as a source an illustrious senator and military man, a veteran of the Second Punic War and, paradoxically, underestimated:Quinto Fabio Píctor.

It is not the first time that we speak here of a member of the prestigious gens Fabia, whose members were considered maiores , that is to say, those patricians who constituted the aristocracy of Rome together with Cornelios, Emilios, Claudios, Valerios and Manilos. The Fabios claimed to descend from Hercules, who would have visited the Italian peninsula before the Trojan War, although they had another reference ancestor in Evander, son of Mercury and the nymph Carmenta, who according to mythology had guided the Arcadians to Lazio , introducing there the Greek gods and alphabet as well as instituting the festival of the Lupercales and being deified at his death.

The ancestry of the Fabios was so rancid that he was also related to Remus, one of the founders of Rome (as opposed to the Quintilios, assimilated to Romulus). In fact, one tradition attributes the cognomen at fovae , the wolf traps, revealing their relationship with one of the children suckled by the Capitoline wolf and with the outlined introduction of the Lupercalias (the Fabios were associated with one of the two colleges of Luperci priests), although Pliny the old preferred the etymology of vicia faba , a broad bean plant that he claims was first cultivated by that gens .

Over time, the nomen Fabio branched out into various cognomen :Vibulanos, Ambustos, Buteos, Dorsos (or Dorsuos), Labeos, Licinios, Máximos and Píctores. The latter owed it to Cayo Fabio Píctor, the first to wear it. Pictor means painter and that character was, indeed, an artist who has gone down in history, above all, for being the author of the oldest documented paintings in Ancient Rome, dating from around 304 BC:those that decorate the temple of Salus on the Quirinal hill recreating the battle that has been identified as the one that General Gaius Junius Bubulco Brutus won against the Samnites.

This work has not been preserved because a fire destroyed the building during the reign of Caligula (or Claudius, depending on the version), but we know of it through references to Pliny the Elder (who did not value them very much, probably because they were made in the archaic Etruscan style and, in any case, pictorial art was not particularly appreciated at that time) and Dionysius of Halicarnassus (who, on the other hand, does praise their grace). But what is really important for what we are dealing with here is that Gaius Fabius Pictor was the grandfather of Quintus.

Gaius had a son whom he named himself praenomen and that it inherited the singular cognomen , becoming consul in 269 B.C. and that, in turn, had an offspring that he named praenomen of his father. The new Fifth Fabius Pictor was born on an uncertain date between 270 B.C. and 254 BC. We know that, according to his lineage, he reached the Senate and received command of a contingent that made up the consular legions that faced the Gallic invasion of 225 BC, during the consulate of Lucius Emilio Papo and Gaius Atilio Régulo.

A coalition of tribes from Cisalpine Gaul made up of Insubrians, Taurisces, Lingones, Taurines, Agons, Salasians and Boii, supported by groups of transalpine Gesatas, crossed the Apennines and sacked Etruria. The consular armies met them with the help of several enemy tribes of the previous ones, such as the Veneti, the Patavini and the Cenomans, defeating the invaders at the battle of Fasulas, near present-day Montepulciano. Pictor apparently distinguished himself in that campaign, so it's no wonder he was given new missions when the Second Carthaginian War broke out eight years later.

That contest was marked by the invasion of the Italian peninsula by Hannibal and one of his most renowned victories, that of Cannae, put Rome on the brink of the precipice. So desperate was the situation that the Senate appointed Quintus Fabius Pictor, who spoke Greek well, to travel to Delphi to consult the oracle and ask the gods for advice on how to face the danger. We do not know what response they gave him, but it was effective, because the brilliant Punic soldier gave up trying to conquer the city. Although, in reality, it had more to do with another member of the gens -by another branch- that would achieve greater celebrity.

It was Quintus Fabius Maximus, alias the Shield of Rome , the man who won the consulate five times and twice the dictatorship to confront Hannibal and who with his unique way of fighting, the so-called Fabian tactic, consisting of avoiding direct clashes to wear down the enemy, earned the agnomen of Cunctactor (translatable as "he who delays"). Paradoxically, and despite the pejorative character of the nickname, he was successful; We already saw it in an article that we dedicated to it some time ago, as you can read in the previous link.

Let us return, then, to the Fabio that concerns us and that, despite the fact that he also had an important military and political activity, what has fundamentally transcended is his work as a historian. His work, presumably titled Gesta de los romanos , has not been preserved. , of which we have news only because of the references to it made by other historians, in the case of those mentioned at the beginning and some others, such as Aulus Gellius or Quintus Claudius Cuadrigario. The former lived much later, in the 2nd century AD, and wrote Attic Nights , a chronicle of Rome whose importance lies precisely in the fragments it reproduces from previous authors, Pictor among them.

The second, on the other hand, lived between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. and therefore he is considered one of the oldest Roman historians. their Annals , History or Rerum Romanarum Libri They consisted of twenty-two books that took a lot of data from Píctor and, in turn, served as a source of inspiration for Tito Livio. Of this, who was professor of the Emperor Claudius, it is not necessary to mention the almost one hundred and a half volumes of his Ab urbe condita , just like the twenty of the Roman Antiquities of Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who lived at the time of Augustus.

All of them practiced what is called annals, that is, the history of Rome, a genre whose paternity is attributed precisely to Quintus Fabius Pictor, despite the fact that it is actually unknown how his writings were formally, except that they were in Greek. . Cicero says that, from the founding of the city to the pontificate of Publius Mucius Scaevola, the pontifex maximus It recorded the most notable events that occurred each year in a table that was posted publicly and included the names of the heads of each consulate and other magistracies.

It was what was called annales maximi or annales pontificum , who subsequently used authors in a personal capacity for their works. That is why many called them Annals like Tacitus did. Also, there were the so-called carmina convivalia , poems and songs of a legendary nature that extolled Roman origins, although by the 3rd century B.C. they had fallen into disuse. And we had to add the Hellenistic Greek historiography, which was beginning to take into account that emerging Rome.

A contemporary of Pictor, Lucio Cincio Alimento, as well as Cato the Elder also belonged to this analyst tradition. (who was the one who began to write in Latin, like Ennius), Lucio Caso Hemina, Lucio Calpurnio Pisón, Publio Valerio Antias, Gaius Licinius Macer, Lucio Celio Antípatro, Sempronio Aselio and Lucio Cornelio Sisena, in addition to those outlined above. Plutarch was not an analyst because his Parallel Lives they are biographies, but he also used Pictor as a source.

And what sources was he based on? To begin with, those about his own family, father, grandfather, etc., as well as the aforementioned pontifical annals and the data that he himself pointed out about his experience against the Gauls and the Carthaginians. He also turned to Greek historians such as Diocles of Pepareto, an author of the third century BC, whose work recounted, among other things, the first steps of Rome and the relationship of its customs and traditions with Greece; that work has been lost and we only know it through the citations of Pictor himself and Plutarch (in his Life of Romulus ).

Another inspiration was Timaeus, a native of Taormina but exiled to Athens by Agathocles (the tyrant of Sicily), author of a book in forty volumes entitled Stories , which ranged from Ancient Greece to the First Punic War, establishing the chronology through the usual system used by Hellenic historians:the lists of the Olympic Games plus the years of the Athenian archons, the Spartan ephors and the priestesses of Argos. However, Timaeus was heavily criticized by Polybius (not in vain nicknamed Epithymeus, i.e. fault finder ) for considering that he had superficial knowledge (not like him, a military expert and statesman), hence he also left Pictor in a bad way.

According to studies carried out by specialists, the history written by him began, of course, with the founding of Rome by Aeneas, a member of the royal family of Troy who managed to escape the destruction of his home by the Greeks to settle in Latium. Like his Hellenic model, Pictor used the Olympiad for dating, placing the start of his homeland in the first year of the eighth, which according to Dionysius of Halicarnassus was around 747 BC. That first part would end with the enactment of the Law of the XII Tables.

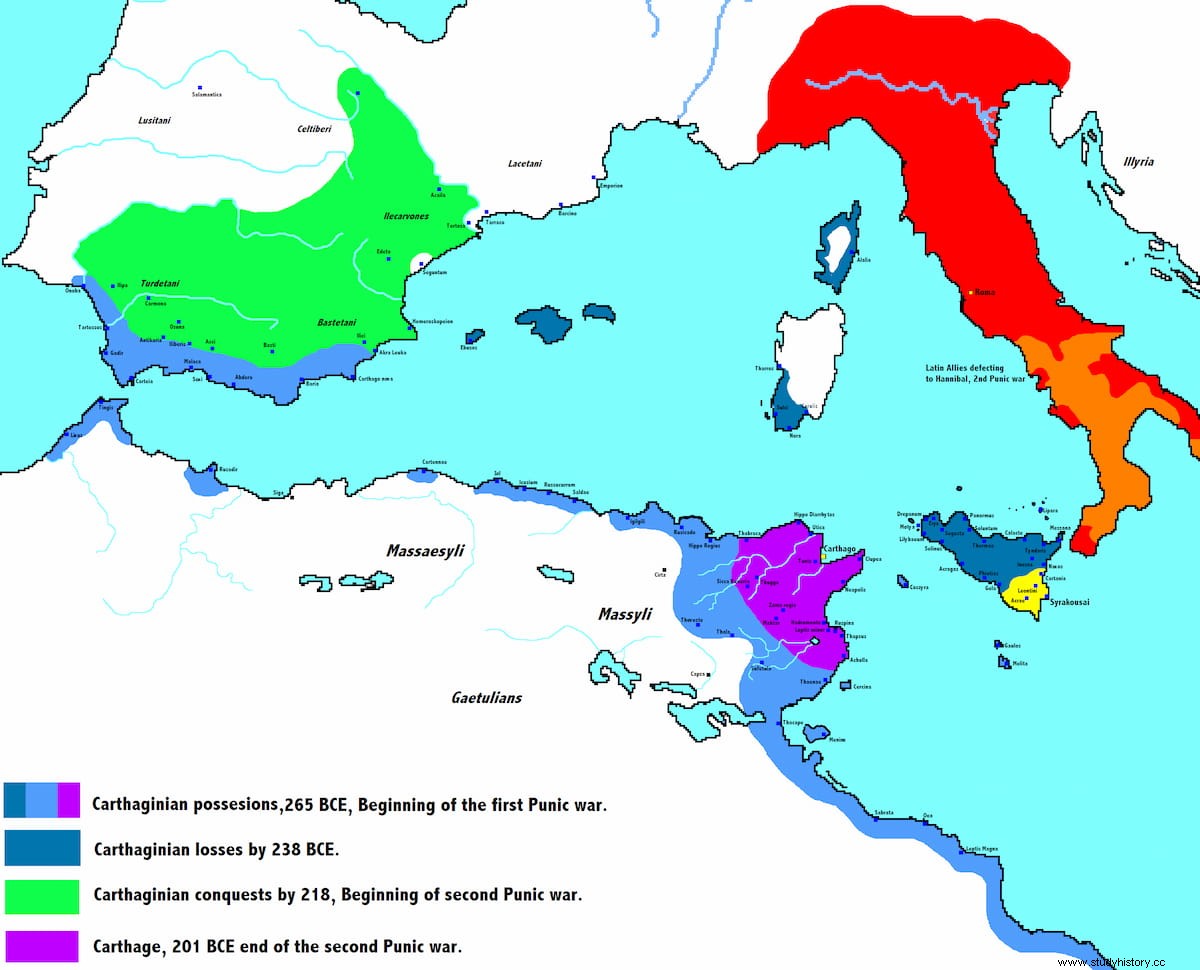

The next would go from the middle of the 5th century B.C. until the First Punic War, narrating the disputes with the neighboring towns, the expansion and formation of the Roman Republic and the progressive domination over the rest of Italy. The third and last part begins in 264 B.C., with the outbreak of hostilities with Carthage, and the end takes place in the context of the Second Punic War, in which, as we have seen, he personally took part and is therefore not objective. blaming everything on the Barcas. By the way, we do not know if the author got to see how that conflict ended.

Such was the Greek influence on Quintus Fabius Pictor that he wrote in that language, although we know from Cicero that later, in his time, a Latin translation called Graeci Annales was made. . In that same sense, it is curious to note that in 1749 an anonymous story was published in English entitled Some account of the Roman history of Fabius Pictor (which could be an indication of what its original title was) which, according to what he says, was made from a manuscript found in the ruins of Herculaneum and written in the Carthaginian language. In reality, it was a typically eighteenth-century pamphlet satirizing the politics and religion of England at the time.

There are exegetes who consider that Quinto Fabio Píctor was not an analyst, since what we know of his work does not conform -at least in its entirety- to the canons of that school, as he does not recount the events year by year except perhaps in its last part. Others, on the other hand, consider him the father of analytics by adapting the Greek historiographical model and enriching it with the Roman documentary tradition, overcoming both and creating a new form of historical discourse.