It is considered that one of the most decisive battles of Antiquity was that of Chaeronea, which pitted the coalition formed by Macedonia, Thessaly, Argos and Arcadia against the Hellenic alliance led by Athens and Thebes. The importance of this conflict lies in the fact that the victory went to the leader of the first, Philip II, which gave him dominion over all of Greece and allowed him to create the so-called League of Corinth to face his most ambitious objective:a campaign against the Persian Empire on its own soil. Something that could not be put into practice, but whose witness was taken by his son, Alexander the Great.

After the Spartan victory in the Peloponnesian War and the consequent fall of Athens, the balance of power in the Greek world was broken. Not only because of the primacy of Sparta, but because Persia knew how to take advantage of the occasion to further disintegrate its old enemies by fostering an alliance between Athens, Corinth, Argos and Thebes, the latter being the one that would emerge as the new dominant power. It hatched in the year 371 BC. due to its hegemonic position in the Boeotian League, which brought together several city-states in that region and liberated Messenia, depriving the Spartans of the workforce that the helots constituted, thus damaging their economy.

However, an exceptional figure was also responsible for this boom:Epaminondas, a statesman and soldier who had a brilliant right-hand man, Pelopidas, thanks to whom peace with the Persians was secured. A good part of the polis The Greeks saw the danger and faced Thebes together, going hand in hand even with ancient rivals such as Athens and Sparta, but they were resoundingly defeated in 362 BC, at the Battle of Mantinea, where the Thebans flaunted their revolutionary wedge tactics with the famous Holy Battalion at the forefront, confirming what had happened in Leuctra nine years earlier.

That would have been the culmination of Epaminondas's work if not for the fact that he himself died in combat, just as Pelopidas had done two years earlier. The result was that confusion spread throughout Greece. Sparta, with its economy touched and the army half destroyed, was sunk; Athens was struggling for a resurgence that did not materialize because the new Attic League that it advocated aroused misgivings; and Thebes tried to maintain his precarious position. All of which seemed to pave the way for foreign powers, since in the meantime, two notable coronations were taking place on the periphery:that of Artaxerxes III on the throne of Persia and that of Philip II on that of Macedonia.

Philip succeeded his brother Perdiccas III in 359 BC. Until then, Macedonia had been a vast though tribal kingdom; Hellenized but despised by the Greeks. However, the new king had spent three years as a hostage in Thebes, which he took advantage of to learn from Epaminondas, whom he would end up surpassing in political astuteness - he has been described as Machiavellian - and military skill. After establishing his position as the new ruler, he spent time both enriching Macedonia and reforming his army into a mighty war machine. Combining this with a clever matrimonial policy, he took control of the northern lands (Chalkidiki, Illyria, Epirus).

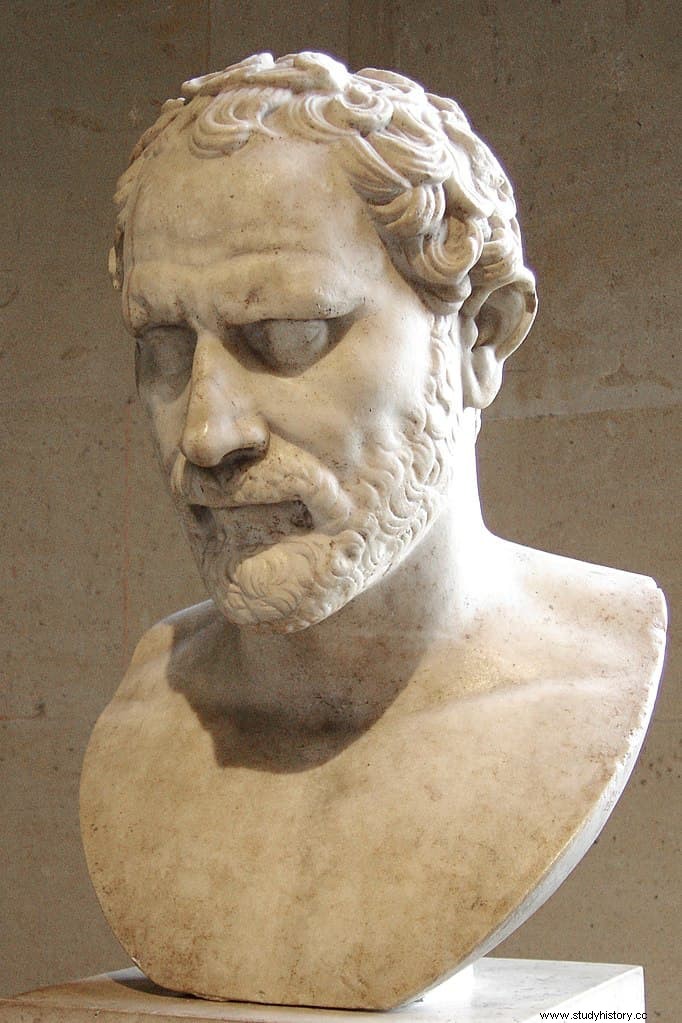

The outbreak of the Social War, a conflict in which various polises Insular (Chios, Rhodes and Cos) faced Athens helped by Byzantium, it served Philip to extend his field of operations to the south. The casus belli it was the sacking of Delphi by the Phocians (because it depended on Thebes):the Macedonians invaded Phocis and took the place of the Thebans as godfathers of the sanctuary. But what was really important was that Philip was advancing towards the center of Greece with the support of Thessaly and the Boeotian League. Athens then began to listen to the warnings that Demosthenes had been making in this regard; his famous Philippics .

The peace negotiations that seemed to have borne fruit at the initiative of the Athenian Philocrates, were based on concessions to Philip that only managed to accentuate his ambition and provoke the condemnation of the first when they failed. Athens was divided between a pro-Macedonian party, driven mainly by intellectuals, and another party led by Demosthenes. There was no way to reach an agreement and in such situations it usually ended up going to war, as was the case. The Macedonian army marched on the Hellespont, the line of communication for the Greek trading states, laying siege to Perinthus and Byzantium.

It was unsuccessful due to the intervention of the powerful Athenian fleet, which meant open confrontation between both sides. Except for the Peloponnese, which remained neutral, the rest of Greece became polarized, with Thebes aligning itself with Athens, forming a new league that included Achaia, Corinth, Chalcis, Epidaurus, Megara, and Troezen. Their combined troops moved to meet the Macedonians to cut them off. It was the summer of the year 338 BC. and the inevitable clash would take place in a Boeotian city called Chaeronea, which would later increase its fame for two reasons:being the birthplace of Plutarch and ending up destroyed by Alexander the Great, who would only leave the house of the poet Pindar standing.

But back to the year that concerns us. In fact, it seems likely that there was some previous skirmish, since Demosthenes records an earlier winter battle, but nothing else is known about it. The location of Chaeronea, located about eighty kilometers west of Delphi, had a special strategic value because it was considered the gateway to the Attica region, hence the Athenians had always tried to maintain a certain guardianship over it. Still, the Thebans preferred to join those traditional enemies considering the Macedonians even worse.

The two armies had a similar number of troops, around thirty thousand infantrymen; Philip also had two thousand cavalry, while the adversary's elite was the Theban Sacred Battalion, made up of a hundred and a half pairs of warriors, each made up of an erastes or veteran plus an eromenos or young people who had a mutual affective and loving bond. Its creator, a companion of Epaminondas named Górgidas, thought (according to Plutarch) that «a battalion founded by friendship based on love will never be broken and is invincible; for lovers, ashamed of not being worthy in the sight of their loved ones, and loved ones in the sight of their lovers, willingly throw themselves into danger for the relief of one another «.

The Sacred Battalion had demonstrated its effectiveness by taking part in victories as renowned as those of Leuctra and Mantinea against the Spartans, for which it accumulated thirty-three years of invincibility. But this time he was going to find something different, new, in front of him. As we said before, Philip had reorganized his army, equipping it perfectly (which included a month's grain ration) and subjecting it to continuous training (according to Polyenus, with marches of three hundred furlongs a day, or about forty-five kilometers), until to the point where it was practically professional. For this, he enjoyed an advantage:having people to spare, since the majority of the population was dedicated to shepherding, not agriculture, and that was a task that their families could do.

Likewise, he provided his hoplites with light armor and the sarissa , a long pike up to five and a half meters long (which protruded four meters from the first line or lochos , granting an advantage over the enemy), although this forced it to be handled with both hands due to its weight (about five kilos, which in turn meant reducing the diameter of the shield). In this way, the front four ranks of the Macedonian phalanx presented a bristling front, with the sarissas of the first sixteen pezetaroi (infants) forward and those of the other three following rows raised between the bodies of their companions. The rest carried them high, to cover themselves from the projectiles and await their turn. They used to supplement their weaponry with a sword, often a kopis .

The usual depth of this imposing formation was sixteen ranks, grouped four by four under the command of a tetrarch. Four tetrachy s formed a syntagm , four phrases a chiliarchy and four chiliarchies a strategy . He had as support the peltastas (light infantry) and the cavalry, made up of the higher classes and the heitaroi (Royal Guard); the horsemen were equipped in the Phrygian style and formed into squads (ile ) of two hundred men, in turn divided into four tetrarchai of forty-nine individuals. They thus signed in four wedges, something that Philip took from the Thracians (and these, in turn, from the Scythians), which gave great mobility and relieved the phalanx of that quality.

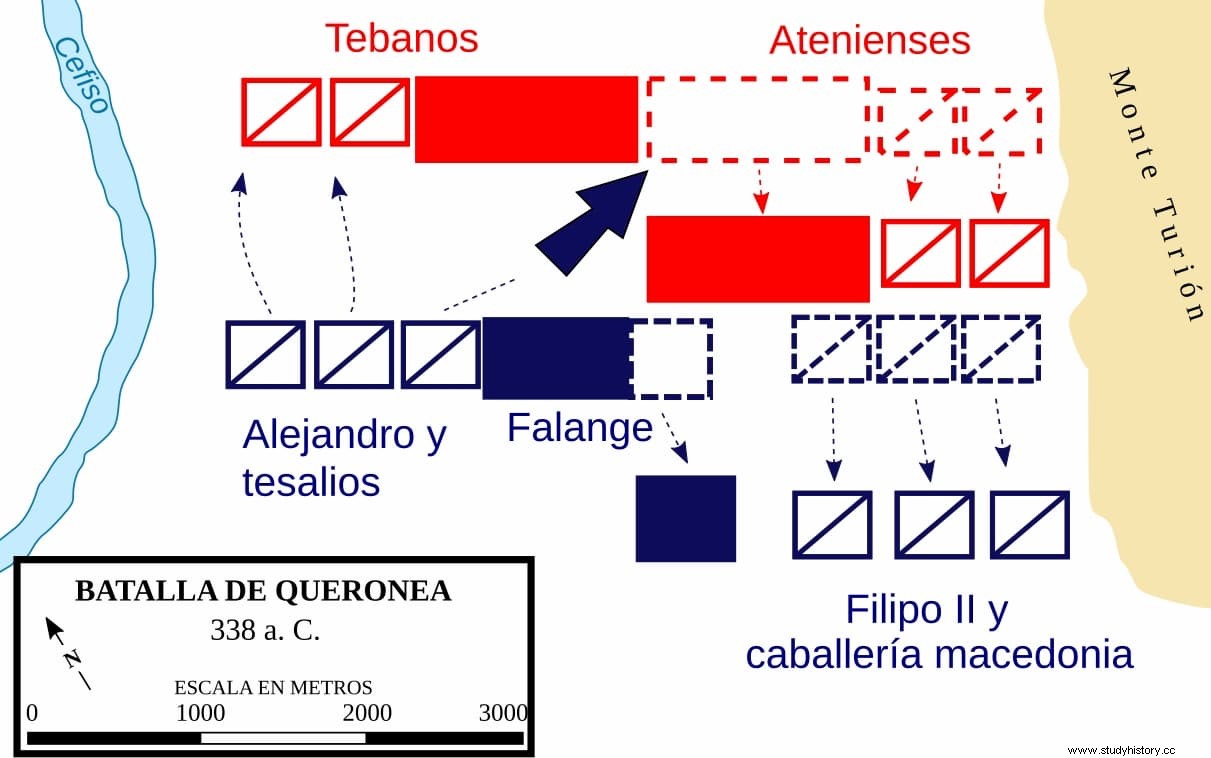

The Macedonians met the enemy on the causeway, forming a four-kilometre line between the Cephisus River and Mount Turion. The Athenians were on the left wing, under Chares and Lysicles, and the Thebans on the right, led by Theagenes (other allied contingents were considerably smaller). Their strong defensive position made it difficult for Philip to attack them. He personally took command of his right wing, made up of cavalry, handing over the center of the phalanx to Parmenion and the left, also on horseback, to his son Alexander, who was only eighteen at the time and therefore had him accompanied by several veteran generals and Thessalian allies.

As contemporary sources of the events are not preserved, it is not known exactly how the battle unfolded, since later accounts are confused and incomplete. The usual version says that, once the fight started, the Macedonian king was able to obtain a quick victory but preferred to drag it out to exhaust the Athenians, less trained than his men. He then feigned a retreat, prompting the others to chase after him, spreading and disarranging the formation. That action ended on a hill, where Philip, seeing that Parmenion managed to break the center of the adversary, suddenly ordered to turn around and then, yes, use himself fully against the exhausted adversary, relying on the cavalry.

He was helped by the fact that, in the meantime, Alexander also disrupted the Thebans and finished off the Holy Battalion, which held the fight to the last of its members. At least that is what Plutarch assures, who left them a beautiful epitaph placed in the mouth of Philip when he saw the mountain of bodies:«Perish those who have been able to think that between such men there could have been nothing reprehensible «. Decades later, a monument would be erected in his honor, the Lion of Chaeronea (which we have already discussed in another article), over the mass grave where they were buried. The excavations found two hundred and fifty-four skeletons, which means that only forty-six of its members would have survived, wounded or prisoners.

The number of casualties suffered by Thebans and Athenians totaled approximately two thousand (to which four thousand captives had to be added), the Macedonians being unknown. Demosthenes was one of the survivors who managed to get to safety in Athens and prepare for the foreseeable siege. It did not come to be produced; Philip considered that city the cradle of Greek culture and did not want its destruction, apart from the fact that he did not have a naval force to blockade it for as long as it would surely resist. Therefore, he limited himself to dissolving the Second Attic League, allowing him to keep his colony of Samos in exchange for the demand to hand over the Chersonesus.

Nor did Thebes suffer the fearful fate that many expected. The conditions of surrender were harsh, with the obligation to pay the ransom of the prisoners and other war expenses, apart from being occupied and replacing its leaders with other favorable but local ones. However, the Boeotian League was not dissolved and the polis were rebuilt of Plataea and Thespiae, which had been destroyed by the Thebans. Other cities received guarantees in exchange for admitting Macedonian garrisons. Only Sparta refused, answering simply and proudly "Yes" to the threat of Macedonia, which consequently invaded Laconia; and, although the capital was respected, the Spartans refused to send delegates to the meeting that Philip called in Corinth that same year.

The result of it were the proposals of koiné eirene (general peace) and a simmachia (alliance), which became a reality in the Hellenic League, better known today as the Corinthian League. To direct it, it had a legislative power developed by a synedrion or council of representatives, with a vote proportional to their importance, and an executive power in the hands of a hegemon which, obviously, would be Philip. Each state would retain its autonomy, but had to contribute a contingent, also proportional, to form a large army and face the common foreign policy.

The Macedonian thus picked up the idea of Panhellenism that had been permeating for some time, hence the tendency towards partial strategic unions of polis which, however, had not yet made the definitive leap to a total union. Isocrates captured this idea in his Panegyric from 380 BC, identifying Persia as the enemy of all and the need to face it together. He said that the leadership should correspond to Athens by the strength of her fleet (after all, he was an Athenian), but after so many years and in the face of changed circumstances, he reassigned that role to Philip. It could not be because he died in 338 BC, but his son Alexander would assume it.