We are going to talk today about the Athenian sacred ships and we cannot think of a more fascinating way to start than by remembering the so-called Paradox of Theseus . It consists of asking if something material remains the same when all its parts are replaced, something that Heraclitus exemplified by explaining that no one crosses the same river twice because neither its waters nor any human being would always be the same (the latter is especially interesting because , as we know, we renew our cells constantly). In the case of Theseus, it is a reference to the fact that, according to a legend collected by Plutarch, his ship was kept in Athens for a long time by periodically restoring its timbers.

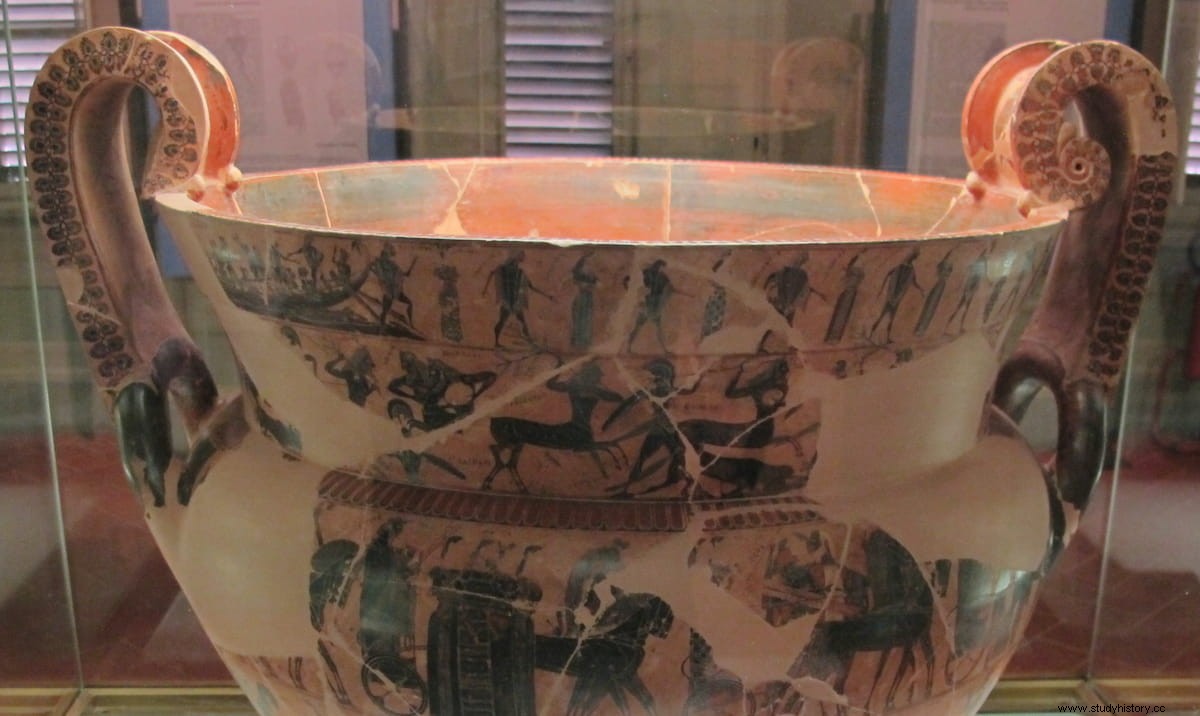

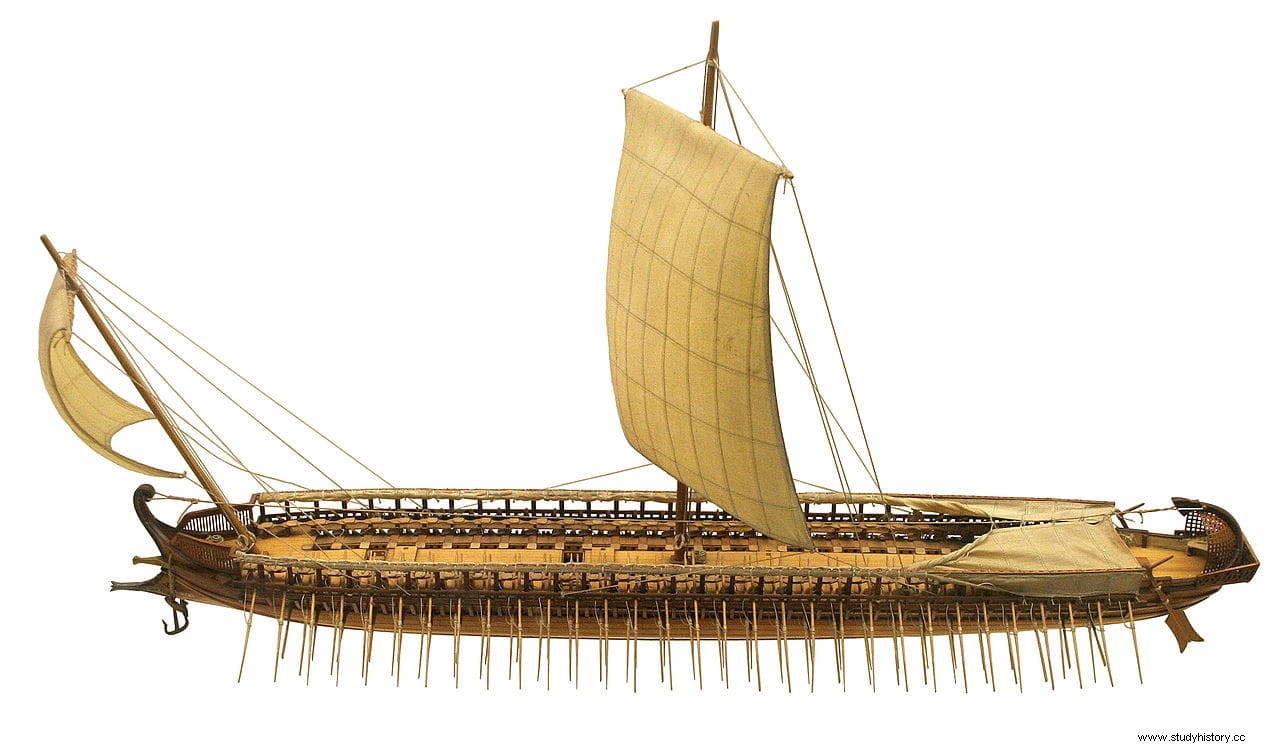

Although the triremes are perhaps the most representative ships of naval warfare in the ancient eastern Mediterranean, there were also other models such as cercuri, liburnas, lembos, hemiolotai , etc. The navarchs used to embark on triaconteros, that is, galleys with thirty oars -fifteen per side-, which were much more agile to move to the different areas of the battle. The ship of Theseus was one, as can be deduced from the painted representation that appears on the famous Vaso François (a 6th-century BC krater showing the hero landing in Athens with the youths he rescued from the Cretan Labyrinth).

His name was Delias , a name that alluded to the festivities in honor of Apollo Delio that were celebrated in Delos, where a delegation of notable Athenians (the deliastas) used precisely a triaconter. The latter must be underlined because it had to be that type of boat, in the same way that to commemorate Theseus' stay on the same island they went in a trireme. These were not capricious choices but rather they obeyed a ritual, which is why Athens always had sacred ships destined for other functions, apart from combat.

Embassies, regattas, religious ceremonies and post office were the most frequent missions for these special ships, although in case of war they joined the fleet to fight or carry out the mission entrusted to them. Some of them have gone down in history with their own name, apart from Delias , whose existence is more part of mythology than reality, apart from the fact that there could have been a ship named like that in Athens that was linked to Theseus (since, returning to Plutarch, it was preserved until the time of Demetrius of Falero, in the 3rd century BC).

Among those whose memory still endures today, we must inevitably cite Salaminia , a messenger trireme from the late 5th century BC. which in those days was one of the two sacred ships that Athens had. The Salaminia It was the official ship in charge of transporting diplomatic representations and high-ranking statesmen (to the Oracle of Delphi, for example, or to Delos, as we said before), so only those Athenians who had citizenship could embark on it. Plutarch compares her to Pericles saying that she only acted when necessary.

She likewise played a curious role during the Peloponnesian War, carrying messages considered to be of rare importance. One of them was the arrest warrant against Alcibíades when he was on an expedition in Sicily, accused not only of the final disaster but also of having desecrated the hermai (heads of Hermes) and the Eleusinian Mysteries, but also of conspiring against democracy. Alcibiades sailed to Catania, where the Salaminia awaited him.; but he refused to go up, arguing that he would use his own boat, which was granted and he took the opportunity to escape.

Alcibíades was not the only illustrious person who could have traveled on board. So did Iphicrates the Elder , a general famous for being the author of the so-called Ichratean reforms, which improved the equipment of the hoplites (replacement of the bronze cuirass by linothorax and the heavy shield aspis for the light pelta , originating the body of peltasts). Iphicrates made use of Salaminia in the expedition that he led to Corfu to help it before the siege it suffered by the Lacedaemonian fleet and a contingent sent by Dionysius I of Syracuse; It was in the year 373 B.C. and it was the last official documented voyage of the ship.

In his work Hellenic , Xenophon praises the good use that the Athenian military made of the boat in that campaign, in which the other great sacred ship, the Páralo also took part. . This was not a triaconter but a trireme and if the Salaminia probably named after the battle of Salamis, in which he would have participated, the name of the other can be translated as "coastal", although it is a reference to one of the sons of Poseidon. The Stop it It is the ship that is most often cited in classical sources (documentary, epigraphic and literary) as an example of its kind, which is logical considering that almost all Athenian rulers sailed on it between the 5th and 4th centuries BC. /P>

In fact, he used to accompany the Delias every year in the theōría , the ceremonial trip to Delos, carrying not only the theoros (religious ambassadors, who had diplomatic rank), but also the offerings that they were going to make to the gods Apollo and Artemis. But he also participated in the war and it is known that he played a role in the battle of Aegospotami (406 BC) against the Spartan army, being one of the ten that were saved and being assigned the mission of bringing the news of the defeat to Athens. Likewise, says Flavio Arriano in his Anábasis that the Stop them he arrived at Tire to transfer the ambassadors Diophantus and Achilles to Alexander the Great, who then turned to him to return to Athens the soldiers taken prisoner in the Granicus and rescued.

Although surely his most famous action was in defense of Athenian democracy:in 411 B.C. he prevented an oligarchic coup d'état in Samos, giving himself the paradox that when he returned to Athens there had also been a seizure of power by the oligarchs, establishing the system of the Four Hundred; consequently, the crew was arrested and only one sailor was able to escape and warn Samos. Since then, the political and civil classes have been separating and alienating. For something Fitelo de Rodas nicknamed the Páralo "club of the people" (which others translate as "club of the people").

To understand it better, it is necessary to know that the crews of the sacred ships were somewhat special. Directed by a tamías (treasurer), who acted as supreme ambassador and, according to Aristotle in the Constitution of the Athenians , was elected by the estates in a show of hands in the Assembly, the members were not recruits but voluntary and select citizens who received a substantial daily salary of four oboles (an obol was equivalent to one sixth of a drachma), whether they worked or No. This generated a group spirit that reinforced the belief that they all probably belonged to the same genos (clan), the Paraloi.

In this sense, we must remember the reforms carried out by the legislator Cleisthenes, a political opponent of the oligarchy who instituted the isonomy or equality of all citizens before the law and converted the Ekklesía (Assembly) in the main decision-making body to the detriment of the elitist Areópago. To limit the power of the aristocratic clans, Clístenes created ten new tribes that were added to the primitive ones (Geleons, Egícoras, Árgades and Hoplitas). The criterion was that they group together the inhabitants of the cities plus their rural environment, dividing Attica into three large regions:Mesogea (central), Asty (urban) and Paralia (coastal). Each tribe that originated a political leader named a ship, possibly with a sacred character.

The fact is that the crews represented a considerable expense for the public treasury, since they added up to hundreds of oarsmen and sailors, to whose payments the maintenance of the boats had to be added, hence the need for each one to have an administrator. That cost increased even more if you take into account that, apart from the Salaminia , the Delias and the Stop it , there were other units of which less news remains:Aristotle and Demosthenes review the so-called Ammonias (which is believed to have perhaps replaced the Salaminia ), while the aforementioned Flavio Arriano does the same with one used by Alexander who would bear the name of Periplous and Philochorus cites two more, Demetrias and Antigonis .

Like the Delias , the Salaminia It was continually restored until the time of Ptolemy Philadelphus and the same can be said of Páralo and the others, hence because of so much renewal the aforementioned Paradox of Theseus arose. However, these ships received such respect that when they were absent Athens postponed pending executions; For this reason, in the year 399 BC, Socrates had to wait a month from his death sentence until he took the hemlock that ended his life, waiting for the Páralo to return. of a mission. This was testified by Plato in two of his plays:the first scene of his play Crito and the prologue of Phaedon .

The explanation contained in the latter is perfect to close the article: