Alanya is a city in the Turkish province of Antalya, a charming enclave that, due to its combination of archaeological heritage, natural landscapes and Mediterranean climate, constitutes an attractive tourist destination, the current economic engine of the city. Alanya is best known to history buffs because it was there that the famous Pompey put an end to the recalcitrant Cilician piracy that, in his growing daring, had reached Roman shores. It was in a battle that has been baptized with the old name of the place, Coracesio.

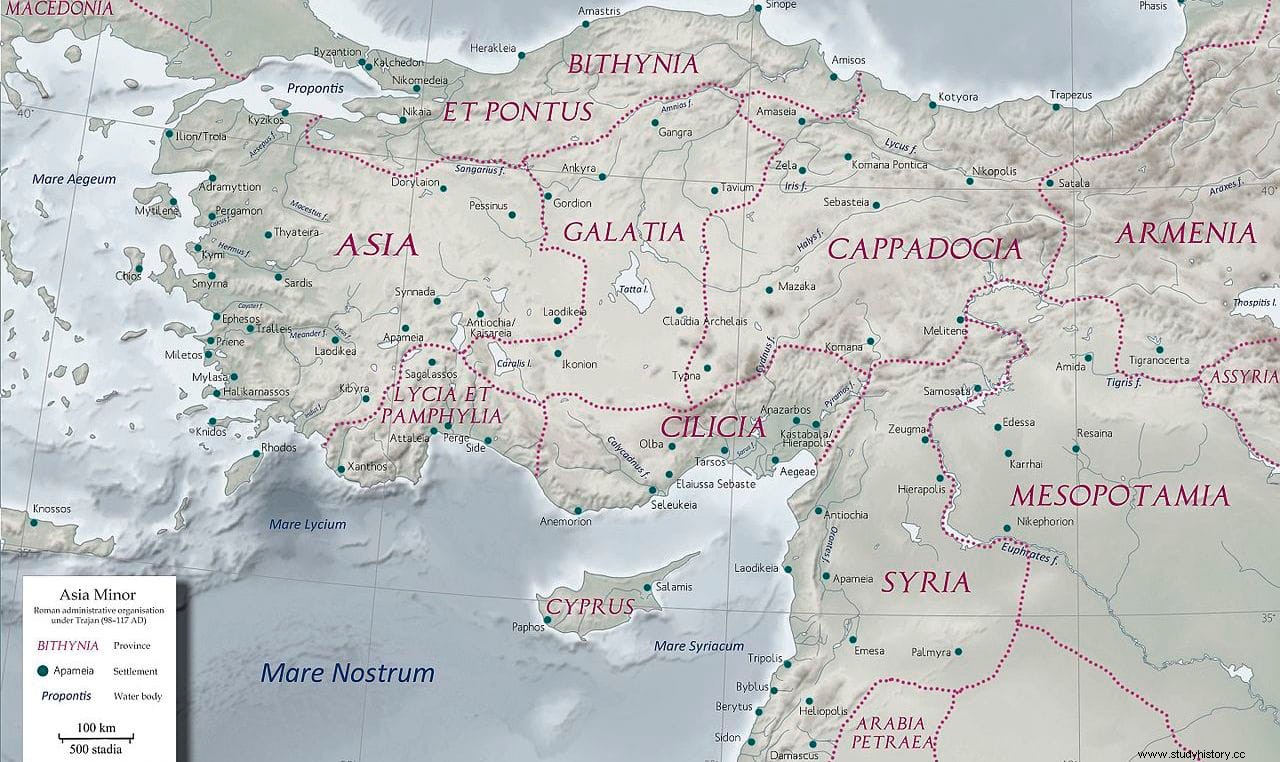

Cilicia, the littoral of Anatolia, was an ancient Persian satrapy that had been the object of disputes by the Diadochi, the successors of Alexander the Great, coming first to the Lagids (Ptolemy's dynasty) and then to the Seleucids (the Ptolemaic dynasty). of Seleucus). The first ones built important fortifications there that turned its port into a perfect and safe place for numerous pirates, something that not only continued but increased with the following thanks to the fact that they expanded and perfected those defenses, already strong thanks to the cliffs that make landings difficult and the scarcity of other inhabited nuclei.

In this way, the Trachea Cilicia (that is, the one that was located between the sea and the Taurus mountains, in front of the flat Cilicia Pedias, preferably inland), became the quintessential refuge of piracy in the Mare Nostrum . And, as we said, it reached such proportions that its raids extended to the Italian peninsula without Rome being able to do anything to prevent it, because it neglected maritime protection, believing itself to be safe. After all, the praetor of Cilicia, Mark Antony Orator, had waged a campaign against the pirates in 103 BC, disrupting their base on Crete (despite the fact that his son Mark Antony Creticus spoiled his father's work in 71 BC), which was completed in 68 BC by Quintus Cecilio Metelo Cretico.

But that ended with the Cretan pirates, not the Cilicians, who took advantage of this lack of vigilance on the part of the Romans, a consequence of the aforementioned misperception of security and the recent civil wars, to reorganize and return to operating more and more daringly. , as Cassius Dio explains:

Its sighting in an area as delicate as the mouth of the Tiber set off all the alarms, already disturbed by the discontent that spread among the population due to the rise in the price of bread, as a result of the shortage of grain caused by the raids on merchant ships. This is how Dio Cassius explains it:

In other words, the threat was multiple:military, economic and social. The humiliation felt in Rome was not minor, as Plutarch reviews:

In fact, no other Mediterranean state had adopted measures in this regard either, because the incursions into the Greek Delos, the main slave market at that time, plummeted the price of human merchandise, allowing that workforce to flow in large quantities to the large towns. and mines. It was the humiliations suffered by the imprisoned Roman notables - whom they ridiculed in grotesque taunts when they claimed their lineage - that finally overwhelmed the patience of Rome.

It was the year 67 B.C. when Aulus Gabinius, tribune of the plebs, took up a never-implemented Senate plan to, by law (the Lex Gabinia ), designate a promagistrate with imperium proconsular for three years, empowered to intervene in all the Mediterranean territories from the Pillars of Hercules to the Black Sea up to a distance of fifty miles inland (about eighty kilometers), with the ability to appoint fifteen legates of the rank of praetor and arm two hundred ships; all financed from the public treasury, calculated at one hundred and forty-four million sesterces. In practice, it was an all-encompassing command that encompassed not only all the Roman domains but also those of other states.

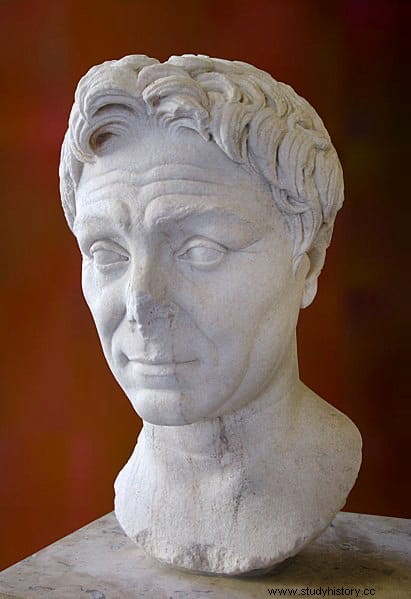

It was foreseeable that the Senate would oppose the granting of so much power to a single man, and so it was; the only one who supported the rogatio Gabinius was Julius Caesar, who long ago had been held hostage by the Cilician pirates and had to pay a ransom for his freedom, though he later marched against them and punished them. That is why Gabinius presented his initiative directly in the elections, in the Forum (what Cicero called popularis ratio ), without needing to propose a candidate because he knew that the people would acclaim his relative Gnaeus Pompey Magnus, under whom he had served in the Third Mithridatic War.

Pompey, indeed, and despite senatorial criticism (a joke at the time spoke of a Pompey navarca as a prelude to Pompey monarch), first pretended not to be interested but then got his imperium he assembled an army of one hundred and twenty thousand foot and five thousand cavalry (approximately thirty legions), appointed twenty-four legates and two quaestors, and embarked them all in half a thousand ships, heading east. The numbers are obviously exaggerated but the important thing is that, Plutarco says, this had an instant soothing effect on the economy:

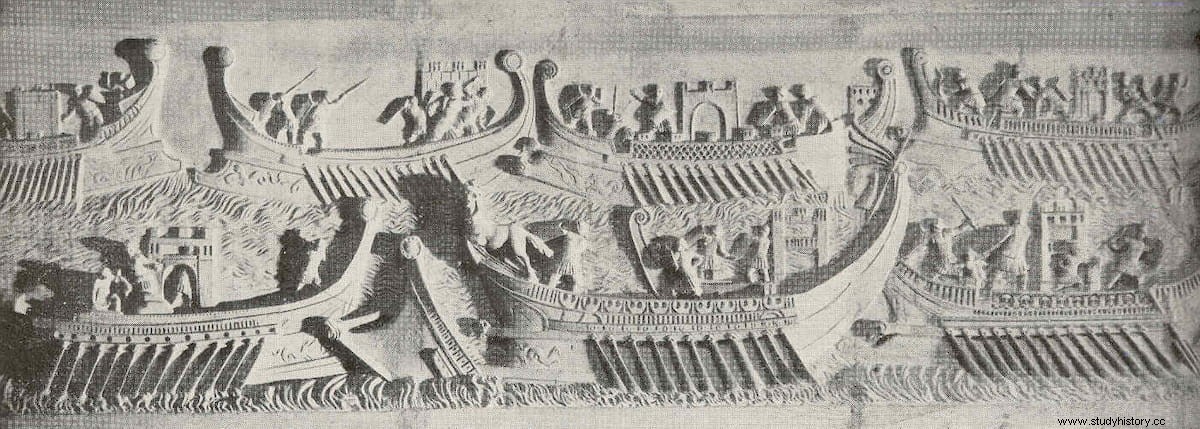

And the first thing he did was clean the Tyrrhenian Seas (the one that bathes the western coast of Italy and the islands of Sardinia, Corsica and Sicily) and the Libyan Sea (the one located between southern Sicily and northern Italy) of pirates. Africa) in just forty days. He then assembled his fleet at Brindisi and leaving his sons Sextus and Gnaeus to guard the Adriatic, set sail again for Athens, where he settled to prepare his strategy. He divided the Mediterranean into thirteen areas, each commanded by a legate with an assigned squadron, so that the presence of Roman ships would be constant and a deterrent. Besides, he reserved two hundred ships under his direct orders.

The plan, which according to Cassius Dio combined a heavy hand with an invitation to come over to his side, worked well. The pirates, accustomed to meeting no resistance, were outnumbered everywhere and defeated or forced to flee; Since they could not find ports in which to take refuge, they fled to their base in Coracesio, where it was clear that the conflict was going to be settled. The naval battle that bears that name was quick and ended with a resounding Roman victory, because, despite his numerical inferiority (although the relationship of forces that Plutarch reviews seems exaggerated), Pompey swept the enemy. Plutarch's narration at that point is rather laconic:

The war had ended with a record duration of less than three months, with spectacular success. According to the various classical chronicles (Strabo, Pliny, Appian...), Pompey killed ten thousand pirates, occupied one hundred and twenty strongholds, seized eight hundred and forty-six ships and took twenty thousand prisoners. Of course, current historiography considers these figures impossible, but they are a clear expression of the triumph of the Republic.

On this occasion, the traditional harshness of Roman justice was not so great, perhaps because executing two thousand prisoners could be excessive. He had taken down Spartacus's rebels shortly before, but that was in Italy; in a foreign land it could backfire. However, Pompey could not allow them to disperse and then come back together, considering that lack of resources and being bellicose is a perfect combination to take up arms. For this reason, the dispersion was carried out in a programmed and controlled manner, through places in Asia and the Greek region of Achaia. Let's go back to Plutarch:

A whole reintegration project that was soon relegated to the background because, although “the war ended and piracy from all places was expelled from the sea” , in the words of the author of Parallel Lives , at that time another current problem was imposed that had been dragging on since 74 B.C.:the aforementioned Third Mithridatic War, an intermittent conflict, which erupted and temporarily subsided to resume, due to the efforts of the king of Pontus, Mithridates VI, in confront the Republic of Rome… for which he had allied himself with the pirates sporadically.

And again it was Pompey who was destined to put an end to it once and for all, by once again accepting the imperium , this time for a rogatio presented by the tribune of the plebs Gaius Manilius, who imitated his predecessor by dictating the Lex Manilia . Which is another story.