In León it is called Guest , in Castile Estantigua , in the Hurdes Genti de Muerti , in Asturias Güestia , in Galicia Santa Compaña … The processions of souls that appear at midnight as a harbinger of imminent death are folk legends that spread throughout the Spanish geography, often as a legacy of the Celtic tradition that, for example, in Ireland have their version in the banshees, female spirits that announce death. But it seems that, in general, these figures are indebted to a common myth in almost all of Europe:that of the Wild Hunt.

In it, a group of ghostly hunters with a black appearance, often on horseback and accompanied by a pack of fierce dogs, demonstrated before some unsuspecting passer-by by carrying out a spooky celestial hunt that predicted their death or something bad for the entire community, whether it was whether it was a war, an epidemic, a plague, a flood, etc. In fact, the apparitions used to be in winter, a season especially feared in other times. The witness could die during the vision if he did not cover his eyes, in which case he would join the entourage.

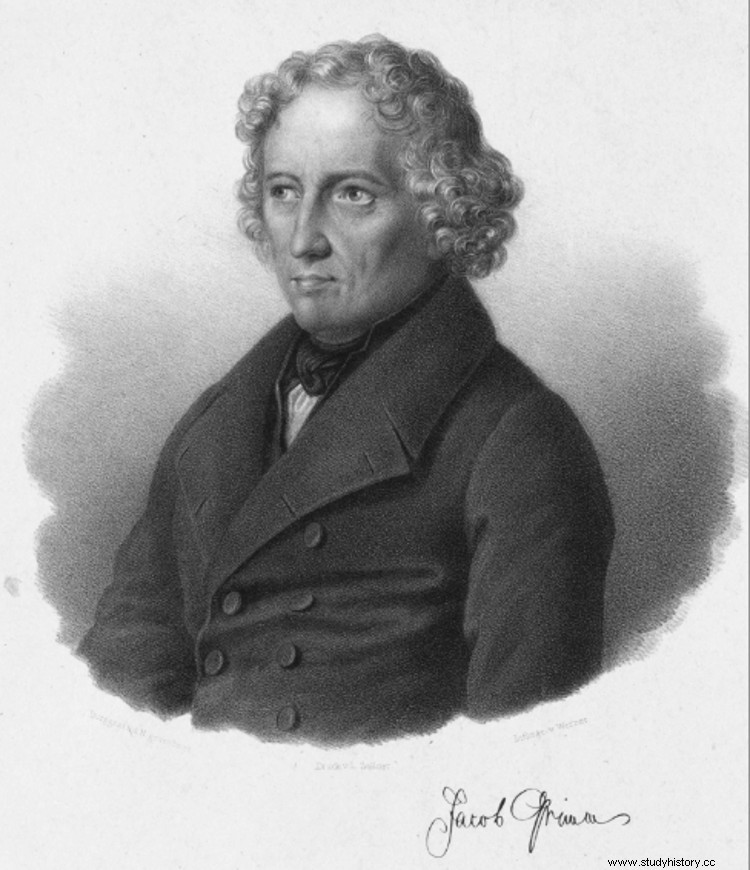

It was the eldest of the Grimm brothers, Jacob, who developed the image we have of that infernal hunting party in his work Deutsche Mythologie, published in 1835. Jacob lived in full romanticism and believed that the folklore of his time had its roots in a pagan ancestral myth, coming from Germanic latitudes, which would have been distorted by the influence of Christianity by transforming the concept of hunting and warrior paraphernalia (the Heruli, for example, blackened themselves in black to fight in the name of Wotan ) into something evil to discredit the old religion.

Jacob was fundamentally a man of letters, not an anthropologist, so he was wrong because, among other things, he was mixing sources from different periods. The researchers of the 20th century corrected their vision by locating the beginning of that history in a more recent date, the Middle Ages, from which it would spread, as we said before, throughout the continent with evolutions and local adaptations developed throughout the passage of time. the ages. Yes, it is fair to recognize the eldest of the Grimm who, at least, was the one who named it:Wilde Jagd.

The famous writer said that originally the hunt was led by a derivation of Wotan, the Teutonic version of the Scandinavian Odin, who would have lost his authentic characteristics to be transformed into a dark and terrible being, often counteracted or complemented by a female entity. However, in each place the leadership of the Wild Hunt was attributed to some similar local figure, usually of ill fame or related to some serious episode in history.

This is the case of authentic characters such as Theodoric, the Ostrogothic king, or the Danish monarch Valdemar IV, under whose reign came the Black Death, later joined by Charlemagne, King Arthur, Frederick Barbarossa and several more. But also other fantastic ones, such as the Welshman Gwyn ap Nudd (the one in charge of guiding the spirits to the other world, like Charon) or the English hunter Herne (a ghost rider that Shakespeare already wrote about).

There are more, from Cain to the Austrian Krampus, the German Frau Holda or the British king Herla, through Herod or Satan himself. It is interesting to add that in Catalonia they have Comte Arnau, a nobleman cursed by his licentious life, condemned to wander eternally on a horse wrapped in fire and accompanied by demonic dogs.

There is no unanimity in explaining the meaning of the Wild Hunt, given the absence of specific sources in this regard. Thus, while some pay special attention to the medieval context and relate it to the belief in the celebration of witch covens, others point to a popular way of interpreting storms and other meteorological phenomena of that type, not missing those who simply allude to superstitious manifestations of witchcraft. faith, continuing the tradition of omens.

The Wild Hunt is documented in some works such as the Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vital, a Benedictine monk of French descent who lived between the 11th and 12th centuries, reviewing many common aspects of Norman England. Vital mentions that in the year 1091 the priest of Bonneval contemplated one of those apparitions, calling it Harlequin's troop; the religious, without a doubt, echoed the Gallic tradition of Mesnée d'Hellequin, an envoy from Hell who led a party of demons in search of souls to take with them and who would later be incorporated into French and Italian comedies with a more burlesque, dressed in a diamond costume.

The hunt is also cited in the so-called Laud Manuscript or Peterborough Chronicle, one of the texts that make up the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and narrates the history of Britain from the Norman conquest to the end of the 14th century. Written mostly in Anglo-Saxon (Old English) prose, a passage dating from the twelfth century mentions a Wild Hunt made up of hellish black-skinned characters mounted on black horses and stags, surrounded by dogs of the same color, as a sign of evil. omen resulting from Henry I appointing a relative of his as Abbot of Peterborough.

The appearance of canines is especially important in Great Britain. Some English counties have even given them generic names such as Yeth Hounds (Devon), Devil Dandy Dogs (Cornwall), Gabriel Hounds (northern) or Gabriel Ratchets (Somerset). In Wales they are called Cŵn Annwn (the Hounds of Annwn, that is, of the Beyond). Now, if something characterizes the legend of the Wild Hunt, it is its great diffusion, since versions have been identified throughout much of the western world.

Thus, the Wilde Jagd baptized by Jacob Grimm was reflected in the English Herlaþing, the Swedish Odens jakt, the Norwegian Asgårdsreia, the Czech Divoký hon or štvaní, the Polish Dziki Gon or Dziki Łów, the Slovenian Divja Jaga or the Italian Caccia selvaggia. . We already saw the Spanish ones at the beginning but, in addition, there are also similar legends in North America, obviously exported by settlers, such as the Canadian Chasse-galerie (in this case the diabolical troupe goes in a flying canoe) or the American Ghost Riders of of which the most famous case is the headless Hessian horseman glossed by Washington Irving in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, derived from Irish, Scottish, and German stories.