Although the usual image we have of the concentration camps in World War II is that of the Germans, in fact the Allies also set up theirs for the Axis prisoners. We saw one of those cases here not long ago, with the half thousand of those commonly called Fritz Ritz built on US soil. Now, in the United States not only the enemy was locked up in camps; citizens of that country also suffered:the nisei , who were the Japanese immigrants or their descendants.

As is known, Japan entered the war well into the war, in December 1941, after a period of growing tension that ended up definitively exploding in the attack on Pearl Harbor . That was what all Americans feared, who lived through days of authentic paranoia , with constant false alarms about the sighting of planes or ships, lights and perception of suspicious radio emissions.

But surely those of Japanese origin experienced greater anguish, because of what this could bring them. So it was. In just over a couple of months, on February 19, 1942 , President Roosevelt authorized his War Department to create concentration camps for the nearly one hundred and twenty thousand inhabitants of oriental ancestry registered in the census.

Installations were set up ad hoc at various points on the West Coast and, following executive order 9006, the FBI proceeded to arrest members of the Japanese community starting with their leaders , accused of being suspected of collaborating with the enemy. No further explanations were given, nor were their relatives told where the accused were interned.

In any case, it didn't take them long to meet with them because a new order, the9102 , enabled the military authorities to transfer them all to prevent any possible sabotage or the provision of information to the enemy.

In this way, tens of thousands of people, including women, the elderly and children, ended up behind the barbed wire after being forced to hurriedly get rid of their properties and belongings -destroying them instead of selling them at a loss was considered sabotage-, in a way unpleasantly similar to what the Jews in Nazi Germany or the Spanish Sephardim had experienced in 1492. Only the process was even faster, because in less than two weeks It was over:in those days it was not uncommon to see buses and trains packed with Japanese Americans traveling under guard to their new destination, nor was it uncommon to see harrowing scenes at stations, as mixed families had to be separated as well.

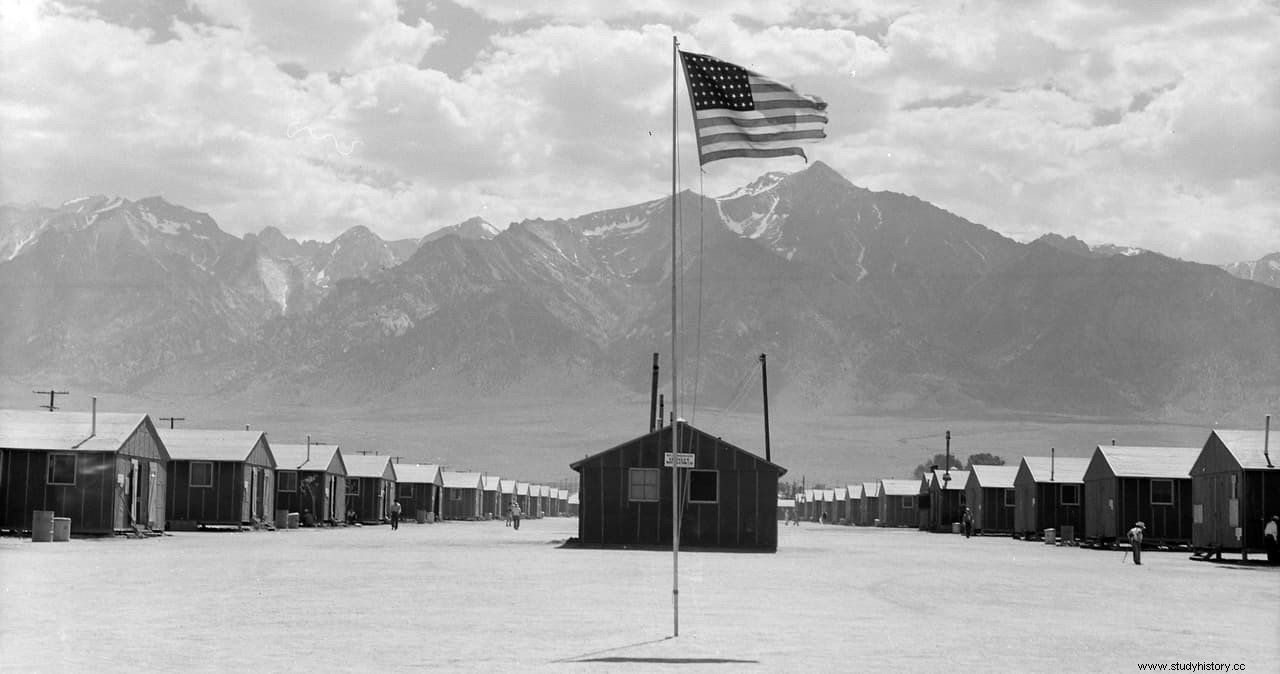

The relocation centers , as they were euphemistically called, used to be located in large areas to build the barracks and be able to watch them without using too many resources:generally in desert areas , with an atrocious climate and far from both inhabited areas and the exclusion zone (coast).

Treatment differed from place to place; it was generally smooth and sometimes a dwelling could be erected outside the fence perimeter; but in other places, where the community leaders were held, they were harsher and some shots were fired from the sentinels. Interestingly, the United States required almost all Latin American countries that they do the same with their Japanese immigrants or hand them over to them; most did.

The operation had a clear racist overtone , given that it barely affected a few German immigrants and citizens of Italian origin were completely exempted. The fact is that the end of the war did not mean an immediate return to normality. Although the War Department had already recommended it since mid-1944, the electoral campaign he postponed it and only after being re-elected did Roosevelt start releasing those nisei that they had shown good behavior or were beyond doubt. They were paid for the ticket back home and twenty-five dollars for expenses.

A year later everyone was at home; at least those who still kept them, because it often happened that, in their absence and due to non-payment of taxes, they had been expropriated . In 1951 the US Government launched a compensation program which returned forty of the four hundred million dollars estimated to have been lost. Those payments continued over the decades and the courts always ruled in favor of the victims; in 1988, Ronald Reagan read an official apology and gave twenty thousand dollars to each survivor.