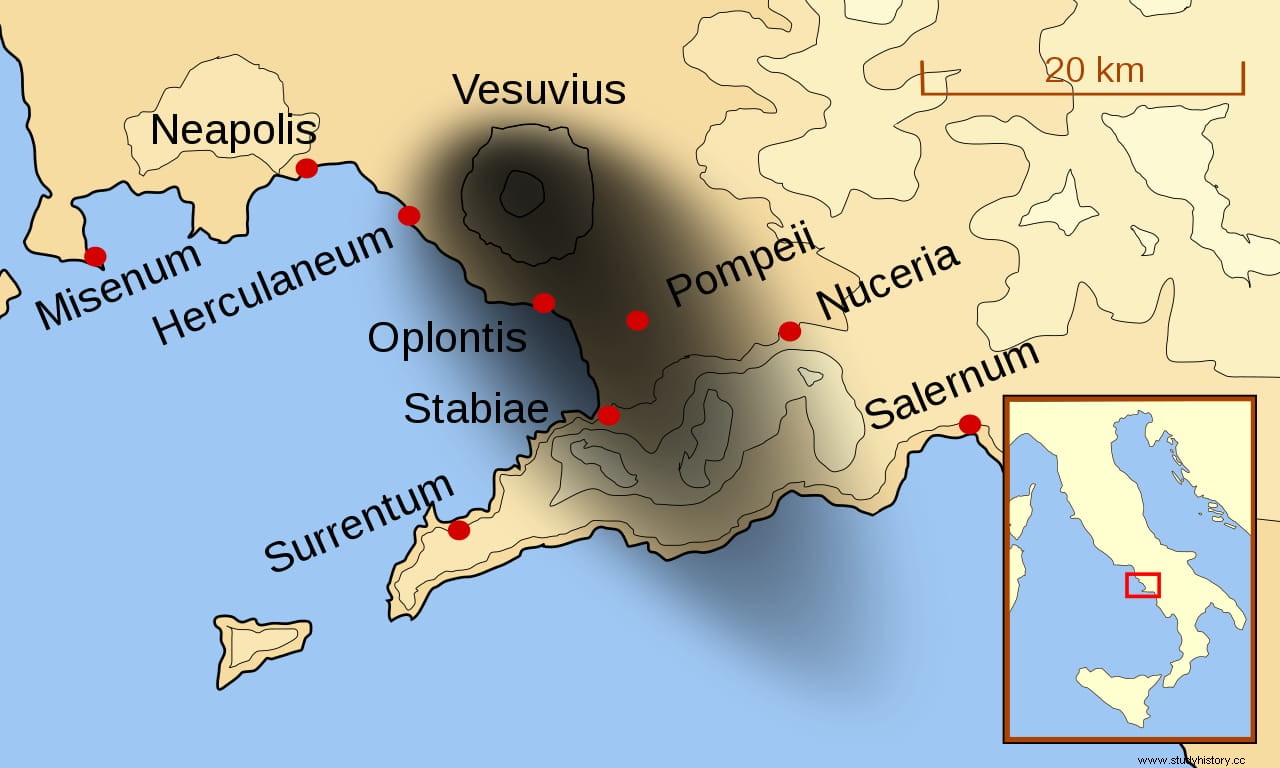

It is well known what happened in the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the year 79 AD. The brutal eruption of the Vesuvius volcano, in the vicinity of which they were located, caused their destruction and the death of thousands of people burned, suffocated and buried under a thick layer of pyroclastic ash that, paradoxically, served to preserve the ruins for centuries. The same ruins that were about to disappear definitively in the summer of 1943, after a devastating bombing in the context of World War II.

Pliny the Younger In his letters to Tacitus, he describes how that fateful day in the 1st century was when his uncle Pliny the Elder died. because of the gaseous emanations when he observed the phenomenon:

Indeed, after the typical rain of volcanic stones came the pyroclastic flow, a deadly burning cloud that first rose into the sky from the crater and then violently descended and spread around, killing everything in its path. Curiously, it would have been a similar sensation if the Pompeians of that time had been present two millennia later, when what fell from the air were not stones but bombs and the effect of the cloud was replaced by the brutal explosions produced this time not by Vulcan's anger but by from the hand of Man.

From March 1943, RAF planes periodically went on missions across the continent to disrupt German lines of communication and transport. In May theAfrika Korps fell leaving North Africa in the hands of the Allies, who on July 10 began the landing in Sicily, completing it in just one month and precipitating the dismissal of Mussolini on the 25th and his replacement by Marshal Badoglio.

The next step was the jump to the Italian peninsula and this implied a series of previous bombardments that were dissuasive for King Vittorio Emmanuel III to capitulate on September 8, five days after the first troops crossed the Strait of Messina and landed in Calabria, beginning its advance towards the north, supported shortly by another landing in Salerno. But before Italy changed trenches (except in the north, where the Germans seized control and rescued Mussolini), Pompeii would suffer a second wave of devastation.

The aforementioned raids Air raids began on August 24 (by ominous coincidence, the same date Vesuvius erupted), with Naples and its important seaport as the target, and lasted eight days straight with a curious extra interest:to determine if it produced better results to attack at night or in full light. According to a study by the Spanish Laurentino García, the British and American squadrons dropped almost two hundred bombs of four hundred kilos each and, as usually happens in wars, caused unexpected collateral damage when several of them fell on the grounds of the ancient Roman city .

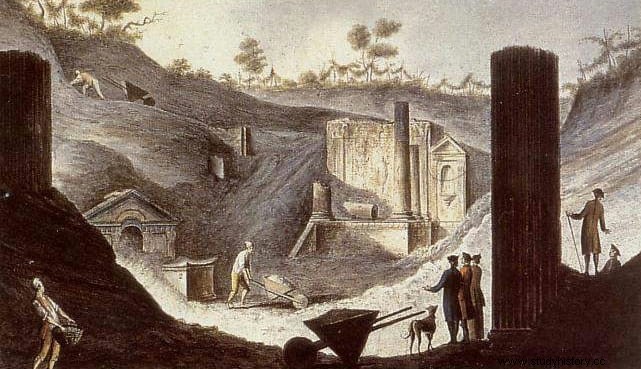

This, which remained preserved underground for so long, had come to light in 1550, when the architect Domenico Fontana made a canal to divert water from the Sarno River to the town of Torre del Greco. However, it is said that he found the erotic frescoes and, scandalized, ordered them to be buried again, for which reason excavations did not begin until 1738, in a series of archaeological works sponsored by the Neapolitan king Charles VII (the same king who would later reign in Spain as Carlos III).

Thus, Pompeii's memory was recovered and from then on the work continued until that fateful summer of 1943. It should be borne in mind that the damage recorded in Pompeii is due to three different stages. The first, an earthquake that shook it in the year 62 causing panic and causing a good part of its twenty thousand inhabitants to flee fearing that it was an eruption of Vesuvius. The earthquake had several aftershocks, hence seventeen years later, when the volcano actually erupted, reconstruction work was still being done.

The second was the described volcanic action, which not only buried the city in ashes but also destroyed architectural structures with the previous tremors that had occurred throughout the days before, according to Pliny the Younger attests. , and then with the rain of stones, which sank quite a few roofs. From 1924, already under the Mussolinian government, a series of restoration works were carried out directed by the archaeologist Amedeo Maiuri; World War II changed things.

The Allied bombs constituted a third stage in that sequence of destruction, by making the Via de la Abundancia (which was the liveliest street in Pompeii), the Porta Marina, the arches that flanked the Forum, the Teatro Grande, the Schola Armaturarum (the building where trophies captured from the enemy were exhibited, which the fascist regime rebuilt for its propaganda potential and whose frescoes that decorated it were lost), the House of Triptolemus, the House of Romulus and Remus, a part of the House of Archaizing Diana, the atrium of the House of Epidio Rufo and the paintings of the House of Sallustio.

Even modern structures ended up pulverized with all their valuable content, in the case of two of the rooms of the Pompeian Museum, among whose rubble were thousands of pieces rescued in the 18th century. In this regard, a curious situation arose, and that is that the most valuable pieces of the museum (statues, jewels...) had been evacuated when seeing that the combats were approaching, but the place where they were taken was nothing less than the Abbey of Montecassino, which between January and May 1944 it would be the scene of another very hard battle and it would be demolished; luckily, just before General Frido von Senger had sent them to the Vatican.

In addition, the bombardment produced secondary effects whose results are still noticeable today:the explosions, even those that did not reach any specific place (which luckily were the majority), stirred up the earth in such a way that since then the rains penetrate easily. in the subsoil, softening it and making it unstable. Murphy's Law caused a new earthquake to take place in 1980 that gave the finishing touch to many corners. A consequence of this is the periodic collapse of some buildings such as the one mentioned in the Schola Armaturarum in 2010 (which on top of that had been rebuilt with reinforced cement, a rather flimsy material).

From that pre-war Pompeii there are twenty photographs on glass plates that show what it looked like then. Currently it has been possible to rebuild some of the buildings, such as the Antiquarian (used as a museum) and it has been protected since 1997 by UNESCO within its World Heritage Site. Despite being one of the main economic engines of Naples, a reduction in public access has been decreed (exhibiting only a third of the city) and a suspension of archaeological excavations to focus on saving what is there now.

So for now, unexploded bombs will not appear again, like the one from 2006, which today is exposed as another part of the site's turbulent history.