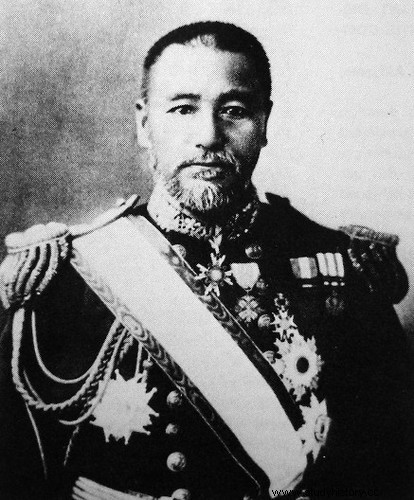

Heihachirō Tōgō was an admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy born on January 27, 1848 and died on May 30, 1934. Trained by the British Navy, he took part in the first battles of the Sino-Japanese War where he obtained the rank of admiral. He commanded the entire Japanese squadron during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, and won a major victory at the Battle of Tsushima.

Who was Togo? Was it like Bismarck, a man "of iron and steel"?... A second Nelson Or an Asian, diabolically cunning, deceitful and cruel? reckless?

the world was talking about this leader and people gazed with curiosity at his portraits in the illustrated magazines. We were also beginning to take an interest in Japan and to wonder what this young nation was basically. We were intrigued by these islanders who, in the space of fifty years, had achieved, a unique tour de force in the history of humanity, a social evolution that had taken five centuries for Western countries.

But this evolution was not only the fruit of fanatical energy, unparalleled wisdom and an extraordinary capacity for adaptation. It proved again, it proved above all, that at the heart of the Japanese race the living forces of the first centuries were still bubbling. The Middle Ages were over from the historical point of view, but its spiritual impulse animated as powerfully as formerly all these modern Japanese.

Japan had not been fundamentally modified by the assimilation of techniques Western. He had only adopted them to better serve the mission he had assigned to himself. He proved to the world that material superiority does not constitute Progress and that it is incapable of making a nation great. Its rise or fall is only the expression of its life force. It is a typically European fallacy to believe that scientific improvement can replace inner unity, faith in one's destiny, everything that makes a country strong. Moreover, the disintegration observed in Europe for a hundred years is proof of this.

In Japan, we repeat, “modernization” and “Europeanization” were only external and practical. They were only the new face inscribed on the old Japanese soul. Thus Togo, who in his youth had been a shaven-headed Samurai carrying two swords in his belt, had become a modern admiral only insofar as he had acquired the most recent principles of Western military technique. He had remained what he had always been:an Asian, wary of strangers, but full of kindness and abandonment towards those of his race, a true scion of the warrior tribe of the Satsuma, steeped in the spirit of Bushido. , of that age-old code which teaches bravery, indifference to pain, asceticism, perfect self-control at all times and in all places, a meticulous sense of honor and finally blind devotion to the Mikado , political and religious leader, direct descendant of God. Deeply respectful of the laws and mores of his country, he was, despite his apparent modernism, the exact opposite of a revolutionary.

As a true Nippon, he was sensitive to the beauty of flowers and cultivated them with love in his garden. He loved the simple life and, like the great conquerors of republican Rome, he returned, once the battle had been won, to this modest house in Tokio where he lived from his marriage until his death, that is to say for fifty-two years. If, to reward him for his victories, he had been offered a palace, he would have refused to live there, for that would have been a fall from the ancient tradition. Glory could not corrupt him. Until the end he remained thrifty, thoughtful and modest. He feared for his family the dissolving influence of wealth and, despite the favors with which his sovereign showered him, despite the pecuniary advantages which his successive offices brought him, he succeeded in dying almost poor.

We draw a parallel between Japan at the time of the Great Change and the First German Empire. This comparison is justified in the sense that these two states had equal faith in their future and owed their rise to the same qualities of discipline, incorruptible honor, silence, tenacity and modesty.

This modesty, this aversion to publicity, were characteristic of great Japanese chefs. The trip Togo and Nogui made to England in 1911 bears witness to this. Silent, self-effacing, the two old men did not understand all the expressions of admiration which rose towards them, the toasts, the receptions, the journalists. Why all this noise? They were not tenors or cyclists, but simply soldiers who had done their duty.

The exploits of Oyoma, Nogui and Togo are worthy of the most grandiose pages of universal history. However, these men never tolerated being placed above their comrades in combat. The results obtained were due not to their merit but to the virtues of the Mikado, to the valor of the troops, to the help of the whole people, and finally to the inspiration of the ancestors whose spirits accompanied them at decisive times. If the leader had not existed, another would have taken his place and accomplished the same work. He was only the sword of his country, but he had to ensure that this sword always remained shining and pure as a crystal.

Togo showed himself violent, bold and obstinate in his youth, and the Marquis Ito, then commander of the naval forces, had to close his eyes to his deviations which sometimes bordered on the refusal of obedience. But a true genius tames himself, and with even more severity than others would. There was in the admiral a balance, a patience, a solidity which, at the same time as his military virtues, only developed over the years and which communicated themselves to those around him. The end of his life was infinitely peaceful and serene. He was revered as a saint. His compatriots were right to see him as their national hero, because, in addition to his unparalleled personal value, he was a living embodiment of all the qualities that make the merit and greatness of this people.