The Mers el-Kébir operation on July 3 had been calculated to coincide with the seizure of French warships in British ports. At 3:40 p.m. that day, detachments of armed British sailors silently approached the ships anchored at Portsmouth and Plymouth. The operation had been carefully prepared to obtain the effect of surprise:it was a success except for the incident which occurred on the large Surcouf submarine, anchored in Plymouth, where two British officers were injured and an officer French was killed. The officers and sailors of the French vessels were interned in separate camps in the Isle of Man and near Liverpool, where they were practically treated as prisoners of war.

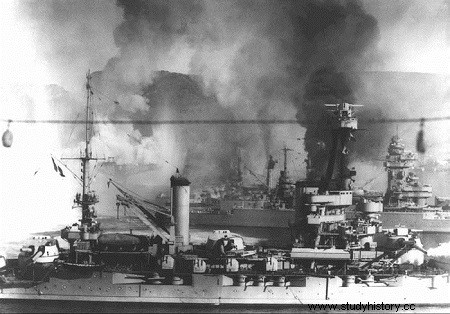

Only a small number joined the Free French Forces. The majority ended up being repatriated to Casablanca by English ships. In Casablanca, the battleship Jean-Bart, unfinished, did not have its main armament so it was not attacked. But in Dakar, her sister-ship, the Richelieu, had on the other hand all her armament. On July 7 a division, composed of the small aircraft carrier Hermes and two destroyers, under the command of Captain Onslow, presented itself in front of the port, and Governor General Boisson received the same ultimatum as that of Oran. He was rejected. A motor boat from the Hermes then entered the port and dropped four mines under the bow of the Richelieu. Due to the shallowness of the water, they did not explode. The next day, at dawn, six torpedo planes attacked the battleship:the only torpedo that exploded damaged her hull. It took a year to repair, due to insufficient local resources.

At Alexandria, Admiral Godfroy's French squadron, consisting of an old battleship, four cruisers, three destroyers, formed an integral part of Admiral Cunningham's Eastern Mediterranean Fleet. The ships of the two nations had worked well together and relations between the two admirals were close and cordial.

Cunningham spoke forcefully against the Admiralty's suggestion of June 29, aimed at s seize French ships on July 3, simultaneously with the Mers el-Kébir operation. He feared that any attempt to use force would run the risk of sinking ships at their berths, thus obstructing the entrance to the port. He managed to come to an agreement with Godfroy for his ships to unload their fuel oil and reduce their crews. But on July 3 Godfroy received orders from his Admiralty to put to sea immediately, and on learning of the Mers el-Kébir affair he no longer felt bound by his agreement with Cunningham.

The English admiral acts with tact and firmness; British officers intervened directly with French officers and crew. Finally, by a written agreement signed on the 7th, the British undertook not to use force and the French to unload their fuel and disarm by putting down the firing mechanisms of their cannons and their lance tubes. -torpedoes.

By taking the decision to use force, the British War Cabinet ran the risk of pushing Vichy to join the Axis. But even if he had known both of Hitler's fleet concessions and of Darlan's measures to prevent the seizure of his ships by the Germans, he would have taken the same measures. Indeed, hadn't Churchill written:"What man in possession of all his faculties would trust Hitler's word, knowing his past and his present behavior? »

However, the fate of the French fleet still depended on Darlan and not on Hitler. Moreover, once the armistice was signed, France was threatened with the worst reprisals if it contravened the relatively moderate naval clauses.

Cunningham had shown, in Alexandria, what could be obtained without bloodshed. The conditions for such an arrangement were more difficult in Oran, but since Admiral Gensoul was about to disarm his squadron when he received the British ultimatum, a little patience and diplomacy might have obtained the desired result without recourse. to violence. The Germans were on the other side of the Mediterranean, and even if they had been able to seize the ships, the French crews would have refused to serve. Months of training would not have been enough for the German crews to arm these foreign vessels.

It is therefore not surprising that Mers el-Kébir provoked feelings of bitterness in France. The Vichy government still controlled one battlecruiser, four cruisers armed with 200 mm and six 150 mm guns, thirty destroyers and seventy submarines. There were about 180 bombers and 450 fighter planes in Africa. Had these forces joined with those of the Axis in the Mediterranean, they would have rendered Britain's position there untenable. But France was beaten and disorganized. His only reprisals for the Oran affair were an ineffective bombardment of Force H in Gibraltar by the French naval air force in the early hours of July 5. Darlan wisely refrained from any further hostile action and gave orders to attack British ships only if they approached within 20 miles of the French coast. Diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom were severed on July 5.

One of the immediate consequences of Mers el-Kébir was that the Germans allowed the French ships to remain fully armed. Those in North Africa were recalled to Toulon, where they were safer from a possible British attack, but also, closer to German control.

Finally, the episode of Mers el-Kébir created a deep feeling of animosity in all the French navy and encouraged the propaganda action of the collaborators. On the other hand, the world was convinced of Britain's determination to continue to fight, come what may.