Æthelstan or Athelstan (c. 894 – 27 October 939) was King of the English from 924 until his death. He is considered the first king of England and one of the greatest monarchs of the Anglo-Saxon period in the country's history.

Son of Edward the Elder, Æthelstan was first recognized as king by the Mercians, and met with some resistance in Wessex, which may have elected his half-brother Ælfweard king to succeed Edward. Ælfweard survived their father only a few weeks, but Æthelstan was not crowned king until September 925. He conquered the Viking kingdom of York in 927 and became the first Anglo-Saxon king whose authority extended to all England. In 934, he invaded the Kingdom of Scotland and forced King Constantine II to recognize his authority. Scots and Vikings ally against Æthelstan and invade England in 937, but he wins a resounding victory over their coalition at Brunanburh.

Æthelstan centralizes the government of his kingdom, with increased control over the production of charters and the summoning of important figures to his councils. The Welsh kings also attend these councils, a testament to their submission to Æthelstan. Her diplomatic activity extended to all of Europe, in particular through the marriage of her sisters to several sovereigns of the continent. Much of the law from his reign survives:his legislative reforms build on those of his grandfather Alfred the Great and illustrate his concern about breaches of the law and the threats they pose. on the social order. Æthelstan is also a deeply religious king, collector of relics and founder of churches. His court became one of the main centers of knowledge in the country and heralded the Benedictine reform at the end of the century.

Never married, Æthelstan leaves no heir to succeed him. It was his younger half-brother Edmund who ascended the throne upon his death in 939. The Vikings took advantage of the situation to retake York, which was only finally reconquered by the English in 954.

Background:Britain at the start of the 10th century

At the beginning of the 9th century, Anglo-Saxon England was divided between four great kingdoms:Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia1. Wessex takes the ascendancy over Mercia under the reign of Egbert (802-839), the great-great-grandfather of Æthelstan, and becomes the most powerful kingdom in the South of England. Viking raids began to hit Britain harder and harder in the mid-9th century. The invasion of the Great Heathen Army began in 865 and destroyed East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia within fifteen years. Only Wessex victoriously resisted its advance, and King Alfred the Great won a decisive victory over the invaders at Ethandun in 8782. Alfred and the Viking chieftain Guthrum shared Mercia. The Danish offensives resumed in the 890s, but they were repulsed by the Anglo-Saxon armies, led by Alfred, his son Edward and his son-in-law Æthelred, who ruled the English part of Mercia with his wife Æthelflæd, Alfred's daughter . On Alfred's death in 899, Edward succeeded him. His first cousin Æthelwold tries to seize the throne, but he is killed in battle in 902.

The war between the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings continues during the reign of Edward. In 910, the Danes of Northumbria attacked Mercia, but suffered a crushing defeat at Tettenhall4. After the death of Æthelred of Mercia in 911, his widow Æthelflæd governed the region alone. Edward and Æthelflæd manage to reconquer Danish Mercia and East Anglia in the years that follow. When his sister died in 918, Edward deposed his niece Ælfwynn and annexed Mercia to his kingdom.

On Edward's death in 924, all of England south of the Humber became part of Wessex. The kingdom of York is ruled by a Viking, Sihtric, but a certain Ealdred maintains an Anglo-Saxon domain around Bamburgh, in Bernicia. King Constantine II rules over Scotland, with the exception of the kingdom of Strathclyde in the southwest. Finally, Wales is fragmented into several small kingdoms, including Deheubarth to the southwest, Gwent to the southeast, Brycheiniog to the north of Gwent, and Gwynedd to the north.

The Anglo-Saxons were the first people in northern Europe to write in the vernacular, and the oldest known code of laws in Old English dates back to King Æthelberht of Kent in the early 7th century. Alfred the Great produced his own code of laws at the end of the 9th century, also in vernacular. Highly influenced by Carolingian law, particularly on subjects such as treason, the maintenance of order, the organization of hundreds or ordeals, it remained in force throughout the tenth century and served as the basis for the codes of later laws. These codes are not rigid regulations, but rather guidelines that can be adapted locally, and oral traditional law retains some importance.

Primary sources

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which dwells extensively on the reigns of Alfred the Great and Edward the Elder, is relatively silent regarding Æthelstan's reign and merely recounts his major victories. William of Malmesbury's Chronicle, written in the early 12th century, offers more information, many of which are unique to him, but their veracity is debated by modern historians. David Dumville does not hesitate to reject Guillaume's account as a whole, which he describes as a "false witness" and whose popularity he regrets. Michael Wood suggests that Guillaume was inspired by a Vita Æthelstani now lost to write his column, a hypothesis taken up by Sarah Foot, who nevertheless points out that it is impossible to say to what extent Guillaume was able to "improve" the 'original. Other narrative sources from all over Europe provide some indirect information, such as the Annales de Flodoard or the Chronique de Nantes.

David Dumville points out that the lack of sources often invoked as the cause of the darkness in which Æthelstan lies is more an impression than a reality. Charters, texts of laws and currencies make it possible to study the management of the kingdom under his reign17. The charters indicate places and dates and show the entourage of the king, and through them, it is possible to retrace his wanderings. This is particularly the case between 928 and 935, when all the degrees are the work of the scribe “Æthelstan A”, who should perhaps be identified with Bishop Ælfwine of Lichfield. This profusion of information offers a singular contrast with the complete absence of charters for the period 910-924, a lack that historians struggle to explain and which makes any analysis of the transfer of power between Edward and Æthelstan difficult. Historians are also increasingly turning to less conventional sources, such as poems written in his honor or manuscripts related to his name.

Youth

According to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan ascended the throne at the age of thirty, which would make him born around 894. He is the eldest son of Edward the Elder, and the only one born of his relationship with Ecgwynn, a very poorly known character whose name appears only in sources after the Norman conquest. These same sources do not agree on her rank:she is of noble birth for some, but one of them describes her as lowly and unworthy of her rank. Its status remains debated. Simon Keynes and Richard Abels believe that Ecgwynn was only Edward's concubine, which would explain why Æthelstan's rise to power is disputed in Wessex. On the other hand, Barbara Yorke and Sarah Foot consider that it was the succession dispute that gave rise to the accusations of illegitimacy, and not the contrary:according to them, Ecgwynn is indeed the legitimate wife of Edward .

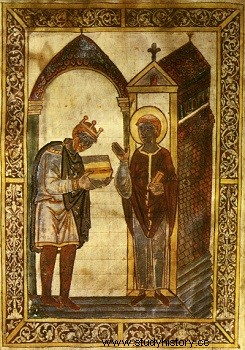

William of Malmesbury describes a ceremony in which Alfred the Great presents his grandson with a scarlet cloak, a jeweled belt and a sword with a gilded scabbard. For Michael Lapidge and Michael Wood, this ceremony represents the designation of Æthelstan as a possible heir to the throne, especially as it takes place at a time when the rights to the throne of Æthelwold, Alfred's nephew, threaten his own line. Janet Nelson recalls that the 890s were marked by difficult relations between Alfred and Edward, and proposes the hypothesis that Alfred may have wanted to divide the kingdom between his son and his grandson at his death.

There is an acrostic poem in honor of a prince "Adalstan", which predicts a great future for him. Lapidge sees it as a reference to young Æthelstan, with a pun on "noble stone", the Old English meaning of his name. Lapidge and Wood attribute it to John the Saxon, one of the leading scholars of Alfred's court, who wrote it on the occasion of the gift ceremony. Wood goes further by presenting the poem as proof of the veracity of William of Malmesbury's account, and by suggesting that Æthelstan may have received an intellectual education under John the Saxon. Nevertheless, Sarah Foot prefers to date the poem to the early years of Æthelstan's reign.

Edward marries Ælfflæd around the death of his father. This marriage is probably due to the death of Ecgwynn, unless she was divorced. He weakens Æthelstan's position, as his stepmother is obviously acting in the interests of her own sons, Ælfweard and Edwin. Edward contracts a third marriage before 920 with Eadgifu, probably after having repudiated Ælfflæd. Eadgifu in turn gives two sons to Édouard, Edmond and Eadred. From his three marriages, Édouard also had many daughters, perhaps as many as nine.

Æthelstan's education probably ended at the court of Mercia, with his aunt Æthelflæd and his uncle Æthelred. He probably took part in the military campaigns against the Danelaw in the 910s. According to an early 14th century copy, Æthelstan granted privileges in 925 to St. 'a pact of paternal piety solemnly entered into with Æthelred, ealdorman of the people of the Mercians'. It is possible that he represented his father's interests in Mercia after the death of Æthelflæd and the annexation of that kingdom to Wessex.

Reign

A disputed succession

Edward the Elder died at Farndon in northern Mercia on July 17, 924. His death marked the beginning of a series of events that are difficult to trace. It is possible that the deceased king wanted Ælfweard, the eldest son of his second wife Ælfflæd, to succeed him, or even to divide the kingdom between Ælfweard, who would receive Wessex, and Æthelstan, who would obtain Mercia. The deposition of Ælfwynn in 918 would in this case have served to prepare the accession of Æthelstan to the head of Mercia. At the time of Edward's death, Ælfweard was in Wessex, while Æthelstan was apparently with his father. He was immediately recognized as king by the Mercians, but it is possible that the barons of Wessex elected his half-brother. Anyway, Ælfweard also dies sixteen days later.

Ælfweard's death does not seem to have extinguished the opposition to Æthelstan which reigns in Wessex and especially in Winchester, where the deceased prince is buried. Æthelstan behaves in the first months of his reign as a purely Mercian king:a charter of 925 concerning lands in Derbyshire has for witnesses only the bishops of Mercia. David Dumville and Janet Nelson propose to interpret his celibacy as a concession that allowed him to be accepted as king, but Sarah Foot sees it rather as a religious choice.

Æthelstan was crowned on September 4, 925 in Kingston upon Thames, a city perhaps chosen because of its location on the border between Mercia and Wessex. It is consecrated by Athelm, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who probably writes or applies a new ordo on this occasion. Inspired by the Frankish liturgy, this ordo sees the king wearing a crown for the first time instead of a helmet. It will in turn inspire the ordo of medieval France.

Resistance to Æthelstan continues after the coronation. William of Malmesbury is about a nobleman named Alfred who seeks to punish the king for his supposed bastardy by blinding him. This handicap would have been enough to render Æthelstan incapable of exercising power, and Alfred would not have incurred the opprobrium reserved for assassins. This character does not appear in any other source, and William does not specify whether he seeks to seize the throne himself or to offer it to Edwin, Ælfweard's younger brother. Relations between Æthelstan and the city of Winchester appear to have remained strained for several years. Frithestan, Bishop of Winchester, did not attend the coronation ceremony, and he did not appear on Æthelstan's charters until 928, in a lower position than his seniority should assure him.

Edwin died in 933 in a shipwreck in the North Sea. His cousin, Count Adalolphe de Boulogne, had him buried in the Abbey of Saint-Bertin in Saint-Omer. Wrongly believing that he had reigned over England, the abbey's annalist, Folcuin, writes that he fled the island "driven by troubles in his kingdom". The twelfth-century chronicler Simeon of Durham accuses Æthelstan of drowning his half-brother, but most historians give him no credit. It is possible that Edwin left England following a failed revolt against Æthelstan. Be that as it may, his death certainly contributes to the easing of tensions between the king and Winchester.

King of the English

In January 926, Æthelstan gave the hand of one of his sisters to King Sihtric of York. The two sovereigns undertake to respect the territory of the other and not to provide support to their respective enemies. However, Æthelstan invaded the kingdom of York the following year, following the death of Sihtric. The king of Dublin Gothfrith, cousin of Sihtric, takes the lead of an invasion fleet, but Æthelstan seizes York and receives the submission of the Danes of the region without firing a shot, and without it being known. whether or not he had to face Gothfrith. The Northumbrians react badly, they who have never before been governed by a king of the South. Nevertheless, Æthelstan found himself in a strong position:on July 12, 927, Kings Constantine of Scotland, Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Owain of Strathclyde. and the Lord of Bamburgh Ealdred come to pay homage to him at Eamont, near Penrith. Seven years of peace in the North follow

The situation in Wales is a continuation of Æthelstan's predecessors:in the 910s, Gwent recognized itself as a vassal of Wessex, while Deheubarth and Gwynedd submitted to Æthelflæd, then to Edward l 'Ancient after 918. William of Malmesbury recounts a meeting at Hereford, where Æthelstan summons the Welsh kings to exact a heavy annual tribute from them and secure the border between England and Wales on the Wye. The rulers of Wales regularly attended the court of Æthelstan from 928 to 935 and appear at the beginning of the list of witnesses on the charters of this period, ceding it only to the kings of Scotland and Strathclyde, a sign of their importance. Peace between English and Welsh lasted throughout Æthelstan's reign, though Anglo-Saxon rule was not favorably regarded by all Welsh:the prophetic poem Armes Prydein, written around this time, foretells a victorious Breton uprising against the Saxon oppressor.

According to William of Malmesbury, the meeting at Hereford was followed by a military campaign against Cornwall:Æthelstan drove the Cornish from the city of Exeter, which he fortified, and established the border of his kingdom on the Tamar. Modern historians view William here with skepticism as Cornwall has been under Wessex rule since the mid-ninth century. Æthelstan founds a new episcopal see for the region and appoints its first bishop, but the Cornish culture and language persist.

Æthelstan thus becomes the first king of all Anglo-Saxon peoples, and de facto overlord of all Britain, N 3. He inaugurates what John Maddicott calls the "imperial period" of Anglo-Saxon kingship (from 925 to circa 975), during which Welsh and Scottish rulers attend assemblies of English kings and testify to their charters. Æthelstan endeavored to conciliate the Northumbrian aristocracy through numerous donations to the monasteries of Beverley, Chester-le-Street and York. He is still considered a foreigner, however, and the northern kingdoms of the island still prefer to ally themselves with the pagan kings of Dublin than with the Christian monarch of Winchester. Its position in the North therefore remains unstable.

The invasion of Scotland in 934

Æthelstan invaded Scotland in 934 for uncertain reasons. It is possible that he finally had a free hand after the death of his half-brother Edwin in 933. The death of King Gothfrith of Dublin in 934 may have weakened the Danish situation and offered Æthelstan an opportunity to impose his domination in the north. The Annals of Clonmacnoise propose another hypothesis:they mention in 934 the death of a sovereign who could be Ealdred of Bamburgh, whose lands would then have been disputed between Constantine and Æthelstan. The twelfth-century chronicler John of Worcester asserts that Constantine had broken the treaty he had made with Æthelstan.

The campaign began in May 934. Æthelstan was accompanied by four Welsh kings:Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Idwal Foel of Gwynedd, Morgan ap Owain of Gwent and Tewdwr ap Griffri of Brycheiniog. His retinue also includes eighteen bishops and thirteen counts, including six Danes. He arrives in Chester-le-Street at the end of June or the beginning of July and offers lavish gifts at the shrine of Saint Cuthbert. According to Simeon of Durham, the armies of Æthelstan sink to Dunnottar, in the northeast of Scotland, while his fleet ravages the region of Caithness, which then probably belongs to the Viking kingdom of Orkney.

The chronicles do not mention any confrontation and do not specify the outcome of the campaign. It is only known that Æthelstan is back in Buckingham in September with Constantine, who is testifying on a charter as subregulus, in other words as Æthelstan's vassal king. He also appears on a 935 charter alongside Owain of Strathclyde, Hwel Dda, Idwal Foel and Morgan ap Owain. The Welsh kings return to the court of Æthelstan at Christmas the same year, but Constantine does not accompany them.

Brunanburh and its aftermath

Olaf Gothfrithson succeeded his father Gothfrith as King of Dublin in 934. He devoted the first three years of his reign to eliminating his rivals in Ireland, and he turned to the Kingdom of York from August 937. He was not strong enough to oppose Wessex on his own, which is why he allied himself with Constantine of Scotland and Owain of Strathclyde to invade England in the fall. This is an unusual season for warfare, usually taking place in the summer, which certainly surprised Æthelstan. He seems to have reacted slowly:a Latin poem taken up by William of Malmesbury accuses him of laziness. Michael Wood salutes his caution:according to him, Æthelstan did not let himself be dragged into battle before he was ready, unlike Harold Godwinson in 1066. Thus, while his adversaries plundered the northwest of the kingdom, he gathered a army in Wessex and Mercia before marching to meet them. The Welsh remain neutral in this conflict.

The two armies meet at Brunanburh, the location of which remains debated. The battle ends in a landslide victory for Æthelstan, while Constantine loses a son and Olaf is forced to flee to Dublin with the rest of his troops. The English troops also suffered heavy losses, including two cousins of Æthelstan. A generation later, the chronicler Æthelweard calls it "the great battle", and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle devotes an epic poem to it, in which Æthelstan is described as the ruler of a British empire.

The importance of the battle is debated among historians. For Alex Woolf, this is a Pyrrhic victory:the campaign seems to have reached a stalemate, Æthelstan's power seems to have been reduced, and after his death Olaf easily seizes Northumbria. Alfred Smyth considers it to be "the most important battle in Anglo-Saxon history", but according to him, it did not have as many consequences as is often attributed to it. On the other hand, Sarah Foot finds it difficult to overestimate the importance of the battle:an Anglo-Saxon defeat would have signed the death warrant of their hegemony over Great Britain. Michael Livingston sees it as "the birth certificate of Englishness", and "one of the most important battles not only in the history of England, but also of all the British Isles".

Death

Æthelstan died on October 27, 939 in Gloucester. Unlike his grandfather and father, he chose not to be buried in Winchester. Following his last wishes, he was buried in Malmesbury Abbey, where he joined his two cousins killed at Brunanburh. They are the only members of the House of Wessex buried in Malmesbury, which according to William of Malmesbury reflects Æthelstan's special devotion to this monastery and its abbot Aldhelm of Sherborne. His remains disappeared during the Reformation, and his tomb at the abbey, fashioned in the 15th century, is therefore empty.

After Æthelstan's death, the people of York appealed to King Olaf Gothfrithsson of Dublin, shattering the Anglo-Saxon hegemony in the North that seemed so solid after Brunanburh. Æthelstan's successors, his half-brothers Edmond (939-946) and Eadred (946-955), devoted most of their reigns to reconquering Northumbria. It was not until 954 that England was reunited, when the last Viking king of York, Eric the Blood Axe, was driven out by his subjects who recognized Eadred as king.