In 2017, the weekly magazine Flair out with a staggering article:from a worldwide survey (by dating site Victoria Milan ) showed that 38% of women and 36% of men would rather spend Valentine's Day with their lover than with their regular partner. No less than 21% of the respondents indicated that they prefer to celebrate Valentine's Day with their lover and partner. Disturbing results, but Flair is always right. We like to use this holiday of love for a short explanation about adultery in the papyri.

The many thousands of papyri that have withstood the test of time in Egypt's arid climate offer a privileged glimpse into the day-to-day reality of Egyptian antiquity. Most of the papyrus texts that have come down to us have never been intended for a wide audience, but only for limited use:letters, contracts, court documents, receipts, bills, and the like, not so different from what you find in the trash today. The authors of these papyrus texts, however, could never have imagined that civilization would one day drive man to the point of extracting these papyri from their wastepaper basket and deciphering them letter by letter to extract from the poor wretches their deepest secrets. This voyeurism has today developed into a scientific discipline, heavily practiced by Leuven antiquarians. But do these papyri also offer a glimpse into the bedroom of our ancestors? What do the papyri say about adultery?

#MeToo

We begin our journey in the New Kingdom, a little over 3000 years ago. Adultery with married women features prominently in a number of Ramessid-era complaints, mainly from the working-class settlement of Deir el-Medina, near the Valley of the Kings. A good example of such a complaint is Papyrus Salt 124 (=P. BM 10055), in which a certain Amennacht his fellow villager Paneb accused of all kinds of evil in front of the vizier (the prime minister, so to speak). Paneb was accused not only of theft, bribery and violence, but also of unchaste acts with a whole host of women:

Paneb had sex with village resident Tuy , who is the wife of the workman Qenna; he had sex with Hul , which is together with Pendwau; he had sex with the villager Hul , who is together with Hesysunebef (…) and when he had sex with Hul, he had sex with Webchet , her daughter; and Aapehty , his son, also had sex with Webchet.

So Paneb made a big deal about it. This may have involved abuse of power:Paneb supervised the works on the royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings and as such had a great deal of influence in the working-class village of Deir el-Medina. #MeToo in Ancient Egypt?

Deir el Medina

Of course, the example of womanizer Paneb should not be generalized. We find a very different view of marital fidelity in P. Leiden I 371 , also from the Ramesid period. In this letter from a man to his late wife - Egyptians often wrote such letters - the former repeatedly emphasizes that he has always been faithful to his wife, both before and after her death. Perhaps this gesture enraptures the romantic souls among us, but recent research by Lana Troy questions the traditional romantic interpretation of this papyrus. According to Troy, the author of P. Leiden I 371 the spirit of his loved one of mischief:although he has always looked after his wife so well, she harasses him from the realm of the dead.

The wise advice of Ankhshesjonqy

Before looking at documentary papyri from later periods, it may be interesting to consider references to adultery in literary papyri. The first reference to adultery is found in the Book of the Dead, a collection of funerary texts that has been used since the New Kingdom to guide the dead during their journey through the underworld and occasionally to house the mummy of Imhotep to bring to life. In the so-called 'Negative confession', pronounced by the deceased when they worship the god of the dead Osiris appear and their hearts by Anubis When weighed, the dead list all kinds of naughty things that they have never committed:they have not murdered, they have not stolen, they have not lied, they have not hurt anyone, they have made no one weep… and they have not cheated. If their hearts prove righteous, they may continue to dwell in the underworld; if not, they are eaten by the hippo lion crocodile Amemet (can you hear it?), an unpleasant second death.

Weighing the Heart in the Book of the Dead of Any (P. BM 10470 , c. 1250 BC)

Equally gruesome is the "Tale of the Two Brothers," preserved on Papyrus D'Orbiney (P. BM 10183) . This story goes – yes! – about two brothers, Anubis and Bata who at first worked together in unison, but soon became involved in a quarrel over a woman. One day, when Anubis's wife came to tell him that his younger brother Bata had tried to seduce her, Anubis decided to kill his brother. Bata barely escaped by offering a quick prayer to the sun god, who conjured up a lake full of crocodiles between the two brothers. This gave Bata an opportunity to defend himself:first, he assured his brother of his honesty by cutting off his own private parts and throwing them into the water, and then he explained that he had not tried to seduce his sister-in-law at all, but his sister-in-law it! When she was rejected, the crafty woman turned the story around in the hope that her husband would take revenge on Bata. When Anubis heard this, he immediately returned home, killed his wife, and threw her to the dogs. The story continues a little further, but in the end Bata and Anubis became king and crown prince and they lived happily ever after.

The so-called Egyptian wisdom texts also offer an interesting look at moral conceptions surrounding adultery in ancient Egypt. The 'Teaching of Anchsjesjonqy ’ (P.BM 10508 et al) can serve as an example. This long series of advice from the imprisoned priest Ankhshesjonqy to his son, according to the box story, not only contains important marriage advice of a general nature (e.g. "the one who is ashamed of having sex with his wife will not have children"), but also refers several grind to adultery. At times the advice is quite witty:"Do not marry a woman whose husband is still alive, lest you make yourself an enemy", "If you find your wife with her lover, comfort yourself also with a (new) bride", or "if a woman does not take care of her husband's property, she has another man in mind." Warnings such as "whoever loves a married woman will be killed on her doorstep" or "whoever takes a married woman on her bed, his wife will be taken on the floor" are much less funny:they bear witness to murder and rape as a form. of honor killings. In general, the wise advice of Ankhsjesjonqy is not very friendly to women.

God, money and sex

The numerous papyri from Ptolemaic Egypt also contain interesting information. A first important group of texts in this context are the temple oaths:these oaths, incidentally an earlier invention, were sworn in shrines in the name of the gods and are usually associated with lawsuits and disputes. They were written down on potsherds (ostraca), which are also part of the papyrological field. More than twenty of these oaths deal with marital problems and several of these texts refer to adultery. For example, a certain Taminis . swore about the end of the 2 the century BC in Djeme (on the east bank of Thebes):“Since my marriage to you to this day I have not robbed you, I have not robbed you, I have done nothing in secret, for more than twenty pieces of silver; I did not sleep with another man during our marriage” (O. BM 31940 =O. Tempelide 7 ). When you take a closer look at this corpus of texts, it is noticeable that the vast majority of these oaths regarding adultery are sworn by women. Another sign of misogynistics? Yes and no:Researchers have pointed to a close connection between these oaths and provisions in Egyptian matrimonial law. A divorce without a good reason could cost a man a lot of money; however, if he could prove that his wife had been unfaithful to him or dishonest about the financial affairs, he owed his wife much less money. Taking a temple oath was a good way to prove this. Men had better not accuse their wives of infidelity indiscriminately:if they finally dared to swear and thus prove their innocence, their husbands had to pay a fine. “Then why not just lie?” you ask yourself today. The answer is simple:the gods in whose name you swore perjury and in whom the Egyptians believed passionately could punish you in all sorts of terrible ways.

The regulations of religious associations are a second important source of information. The Rules of the Association of the Temple of Horus Behdety ’ (P. Lille Dem. I 29 , 223 BC) punishes adultery with the wife of another member of the association with exclusion from the association and a fine of 2 kite silver:not insurmountable in itself when you know that this amount corresponds to about 12 daily wages and that you were fined four times more if you told another member of the association that he had leprosy, when that was not true. You had to be careful in the 'association of the crocodile' in Tebtynis:there you paid 300 deben in case of adultery. or 3000 kite (P. Prague , 137 B.C.). It is difficult to estimate the exact value of this sum of money, due to the instability of the Ptolemaic monetary system during this period, but in any case it seems to be a considerable amount:for 300 deben in this association you might as well beat your superior three times or accuse three colleagues of leprosy. Perhaps the crocodile club was recently rocked by a scandal?

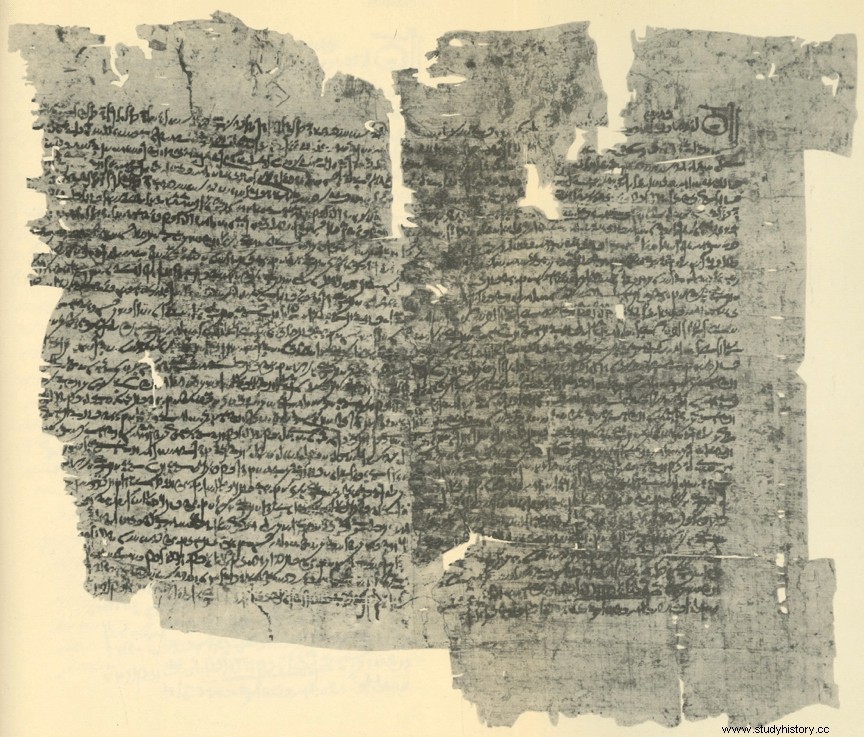

Demotic Rules of the "Association of the Temple of Horus Behdety" (P. Lille dem. I 29 , 223 B.C.)

Crimes passionnels

The last papyrus to be reviewed here dates from the late 4 de century AD BGU IV 1024 is an excerpt from a legal handbook, which contains three summaries of murder trials. The first case concerns a man who caught his wife in the act with a lover; the latter was able to flee, but the woman was stabbed by her husband. The second case, “against one who loves his girlfriend too much,” is very similar to the first, but in this case the man and the adulterous woman are not married. Finally, the third case concerns the murder of a prostitute by a jealous Alexandrian senator. These 'crimes passionnels ' recall the Ptolemaic petitions of the twin sisters in the Memphite Serapeum, already discussed on this blog:the mother of these girls had asked her lover to get rid of her husband. The fate of the first man from the legal textbook is unknown. In the second case, love was considered a mitigating circumstance and the murderer was "only" sentenced to lifelong hard labor in the mines. The Alexandrian senator, in turn, could count on less leniency:the judge sided with the prostitute, a pitiful creature who was forced to sell her body, and sentenced the senator, who had disgraced his position, to death. Even today, love madness is invoked in some legal systems as a mitigating circumstance in murder cases. In Belgium, this fact was removed from the law in 1997. Still not completely reassured? Then you should celebrate Valentine's Day with your own partner!