In 1840 a young archaeologist named Charles Thomas Newton, a follower of Winckelmann's theories about the scientific study of classical archaeology, obtained the position of assistant in the antiquities department of the British Museum. On the other hand, a rather modest position for someone with ambitions.

However 12 years later, in 1852, his tenacity would bear fruit when he was appointed British vice-consul in the city of Mytilene, on the Greek island of Lesbos, at that time still under Ottoman rule. His functions included, among others, looking after the interests of the British Museum in the area , which more or less meant taking all those archaeological finds that he considered important or valuable and sending them to England.

He must have done very well what he had been entrusted with, since in April of the following year he was appointed consul in Rhodes. Only a year later he left office to devote himself to archaeological excavations on the island of Kalymnos, where he brought to light a temple of Apollo and an ancient city whose name has not yet been identified.

But his dream was to find the exact spot where the famous Mausoleum at Halicarnassus had been, excavate it and send the remains to London. Which he got the British Museum to subsidize in 1855.

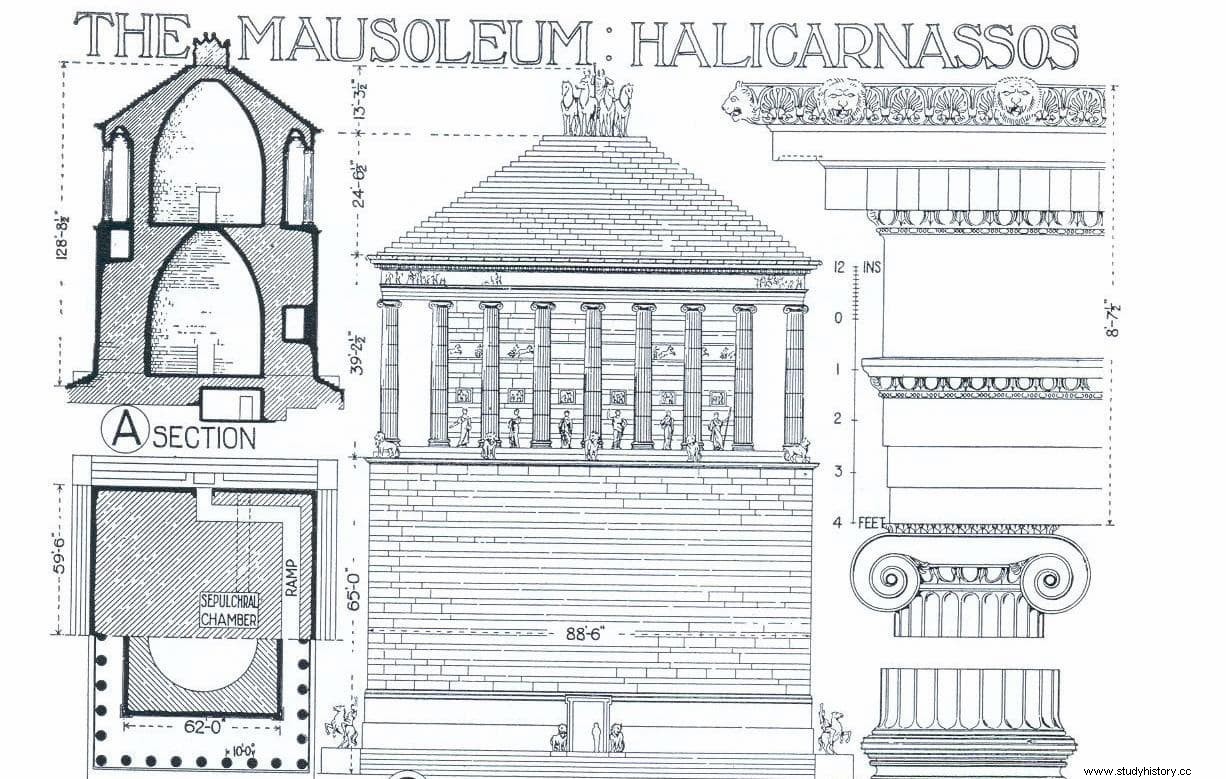

The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus was the last of the six missing wonders of the ancient world, as it is known that it was at least partially still standing in the 15th century (as everyone knows, of the 7 wonders only the pyramids of Egypt remain today ). The funerary monument of Mausolus, ruler of the city of Halicarnassus (present-day Bodrum in Turkey) and satrap of the Persian empire, and his wife Artemisia II had been built between 353 and 350 BC. by the Greek architects Satyrus of Paros and Pittheus of Priene.

The construction, which housed the mortal remains of Mausolus and his wife, was a four-story structure that reached 45 meters in height. It had a perimeter of about 134 meters and each of its parts was adorned with sculptural reliefs and statues made by the best Greek artists of the time:Leochares, Briaxis, Scopas and Timoteo. Crowning the entire ensemble was a large marble chariot, the work of Pittheus of Priene himself.

The model, which consisted of a high-rise quadrangular podium or base on which a building in the shape of a Greek temple was arranged, drew its inspiration from the Nereid Monument, erected in the nearby Lycian city of Xanthos (it can be seen today, reconstructed, in the British Museum) around 400 BC

The tomb was already considered in its time as a great triumph of Greek art, and achieved such fame that even the Roman emperors, three centuries later, built mausoleums and the word ended up designating any tomb built on the surface.

The mausoleum stood invasion after invasion:Persians, Macedonians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs… It seems that in the twelfth century it was still intact when Eustacio, a monk who would later become archbishop of Thessaloniki, saw it, since in his commentary on the Iliad wrote:was and is wonderful . In fact, it stood on the ruins of Halicarnassus, intact, for 16 centuries. But when the knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem (Hospitals) arrived in 1402, it was already in ruins, only the base was recognizable. The shattered columns lay on the ground as did the bronze chariot. It is therefore believed that at some point in the 14th century it collapsed due to one or more earthquakes.

The fact is that the hospitaller knights used many of the stones from the mausoleum ruins for the construction (and later reinforcements) of their castle of San Pedro in Bodrum (name with which Halicarnassus was already known at that time). They were even able to retrieve some of the reliefs and include them on the castle walls. These reliefs were later removed by Lord Stratford of Redcliffe and sent to England.

However, by the 19th century the ruins had been so buried that no one could identify where the imposing monument had once stood. And this is where Charles Thomas Newton appears, who arrived in Bodrum in 1855 with the mission of locating the exact place where the Mausoleum had been and recovering everything he could from it.

Newton studied all references to the monument from historical sources that he could find, combining them with field study of the topography of ancient Halicarnassus. Vitruvio, in his ten books De Architectura written between 27 and 23 B.C. gives your situation quite accurately:

Newton realized that the place pointed out by Vitruvius coincided with the news reported by Professor T.L. Donaldson who, several years before and after his visit to Bodrum, had written that a little north of the Aga's palace there were many fragments of column shafts, scrolls and other ornaments of a magnificent Ionic building equal in taste, finish and materials to the most refined buildings of Athenian art .

However Newton realized that the site in question was so heavily laden with houses and garden walls, and so cut into small plots, that it was not until after a long familiarity with the soil that I recognized its true characteristics. Even more, as he goes on to explain in his memoir of the discovery:a peculiarity of this place was the unevenness of the surface of the fields, in which the hills and hollows were produced so capriciously that they were rather the result of ancient excavations than from a natural formation. This anomalous configuration of the ground, and the impediments that the houses and enclosures offered to a general view, prevented me for a long time from tracing the outline of the great platform on which the Mausoleum stood.

So he chose to start the excavation work in one of the adjacent farms, given the impossibility of doing it in the place where he knew which were the remains of the Mausoleum. Within two days he began to extract from the ground fragments of marble and reliefs, column drums and remains of statues. Everything indicated that he was going in the right direction. But he was held back by the impossibility of negotiating and agreeing with as many homeowners as he had ahead of him.

So he began to dig tunnels to explore the surrounding land. Thanks to them he discovered some walls, a staircase and three of the corners of the foundations of the Mausoleum. With that knowledge he knew what plots he had to buy from Bodrum's stubborn neighbors.

Newton's excavations brought to light the remains of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus as well as a multitude of reliefs and sculptures, including those of the Mausolus themselves and his wife Artemisia. However, upon entering the burial chamber there was no trace of their bodies. Researchers believe that either they were cremated and therefore only the ashes in an urn would have been in the Mausoleum, or looters made them disappear over the centuries.

The Mausoleum would be extensively excavated and studied later, between 1966 and 1977 by Professor Kristian Jeppesen of the University of Aarhus, until today the main authority on the matter.

As for Newton, in 1858 he would make impressive discoveries at Cnidus, an ancient city in southwestern Anatolia, where he found the famous 2nd century BC Lion. In 1860 he would be appointed consul in Rome, and the following year he would take up the newly created post of keeper of Greek and Roman antiquities at the British Museum. He would die 34 years later having been named honorary director of the German Archaeological Institute, and honorary member of the Academy of the Lyceum of Rome.