Scattered around various places in the city of Rome, fragments of a curious inscription from the end of the 1st century BC appeared over the decades. which was originally part of a tombstone or funerary stele dedicated by a man to his deceased wife.

Today that inscription is important for several reasons. In the first place because it is one of the few first-hand sources that allows us to know what life was like for women in ancient Rome. It also provides a good overview of the Roman law of inheritance and marriage. And secondly because, with its 132 lines of text, it is the longest surviving personal inscription from that time.

In addition, it contains the small mystery of whether the one alluded to in the inscription may be the Turia from whom the so-called Laudatio Turiae takes its name. (praise of Turia), since some facts mentioned in it coincide with those attributed to the famous wife of Quinto Lucretius Vespilón. However, the inscription does not mention her name.

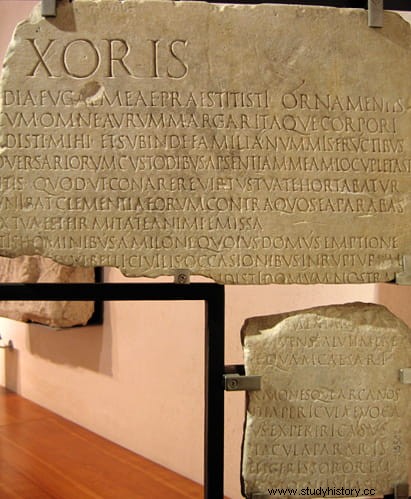

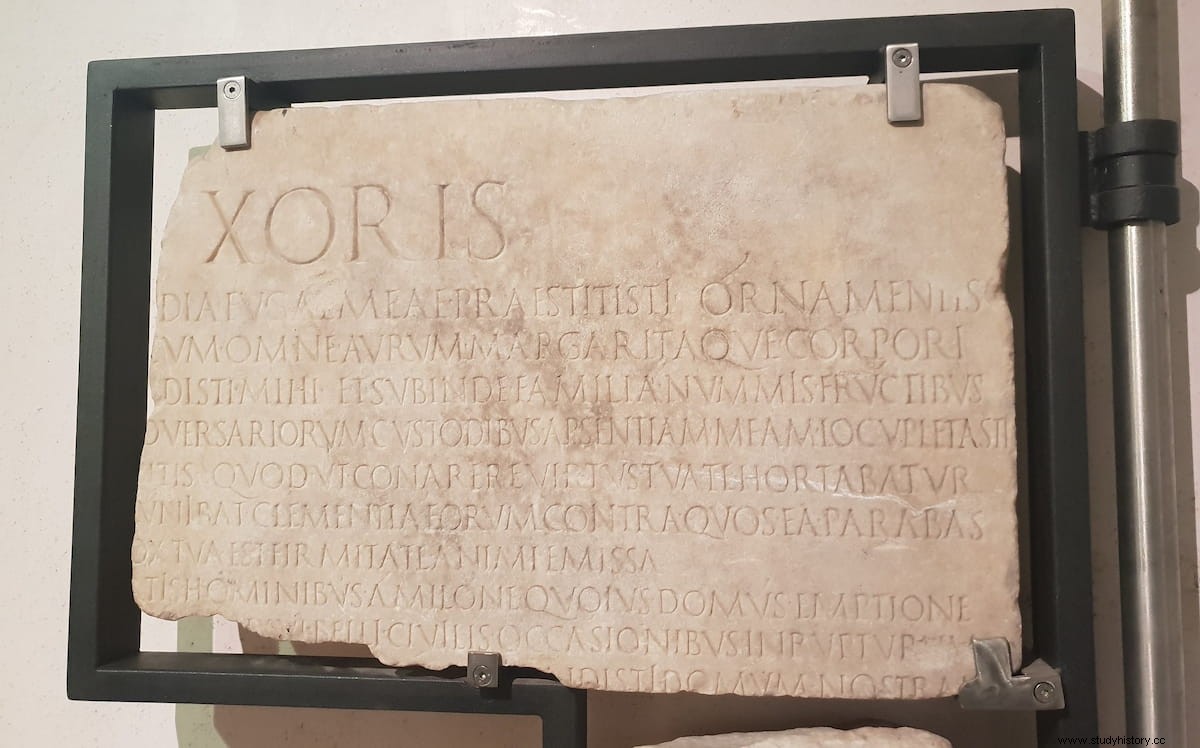

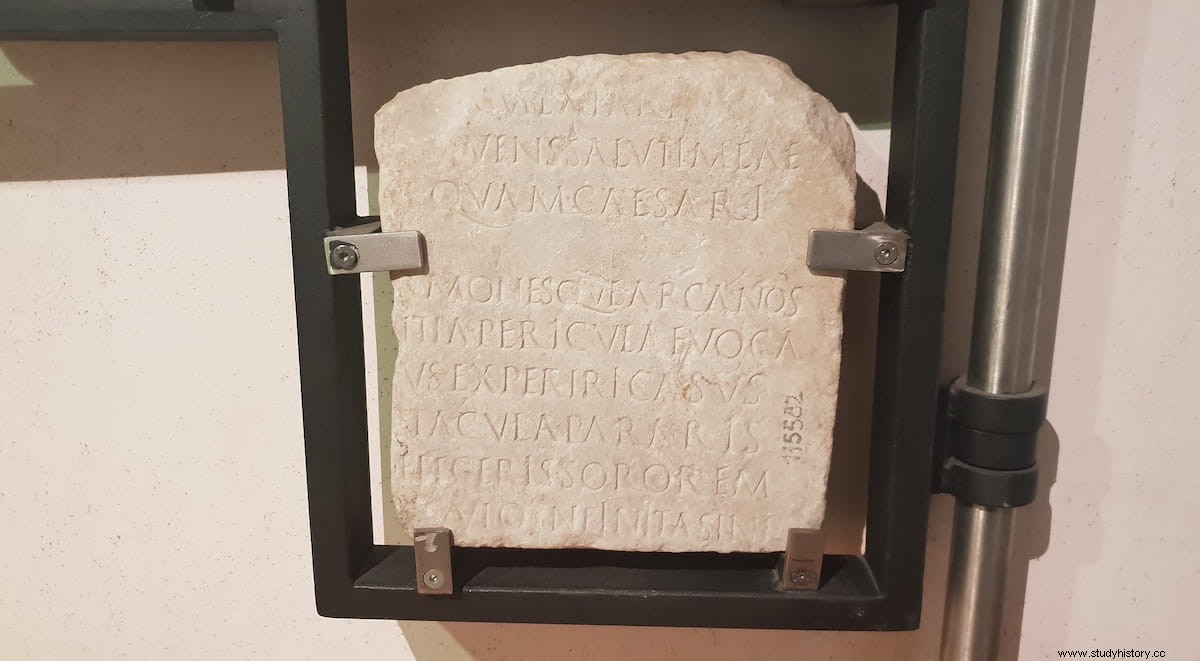

So far seven fragments have been found, which were part of the original inscription carved on two stone slabs about 2.6 meters high and 90 centimeters wide each, which possibly framed a statue of the deceased and her husband. . It originally had about 180 lines of text, of which about 132 are preserved in the fragments.

The great dispersion of these fragments throughout Rome seems to be due to the dismantling of the tomb around the 3rd century AD. Two of the fragments found had been used to cover the niches of the catacomb of Saints Marcellin and Peter on the Via Labicana, built around that time.

Of the three fragments on the left side only copies from the 17th century exist, the originals have been lost. And currently only the last two fragments found are on display, which can be seen in the museum of the Baths of Diocletian.

The inscription, in which the widower praises the virtues of his wife (they had been married for 41 years), begins by telling how the wife was orphaned and had to fight for her inheritance:

He continues talking about her marriage, in which they had no children, about her masculine virtues (virtus ) such as bravery, of the feminine (he didn't upset the social order), and how he helped him when he was outlawed for siding with Pompey in the civil war against Caesar.

She later asked the triumvir Lepidus to extend Octavian's edict of clemency to her husband as well. Although Lepidus went so far as to kick her when she threw herself at her feet, she stubbornly insisted and succeeded in her request. Her husband regained his civil rights and was able to return to Rome.

Having hoped in vain for them to have children, she offered him a divorce with the simultaneous relinquishment of her fortune so that he could have children with another woman. He firmly refused.

And even though she asked him not to spend too much on her funeral, the heartbroken widower erected an expensive tomb for her, and a laudatory inscription, so that everyone who saw her would know who she had been.

The name of neither of the spouses appears on the lines that have been preserved. Some scholars, beginning with Theodor Mommsen, surmised that they could be Quinto Lucretius Vespilón and his wife Turia by him.

The similarities are interesting, Vespilon sided with Pompey in the war (even commanding one of his fleets in 49 BC) and was outlawed by the triumvirate in 43 BC. Later, Octavio pardoned him thanks to his wife Turia (or Curia), with whom he was married for 40 years. However, today specialists reject this identification.

Among the reasons to doubt this is the fact that the widower does not mention his rank (he was appointed consul by Augustus in 19 BC) in the inscription, something unusual. And also that Turia's deed, although remarkable, should not have been unique, something that the laudatory text seems to recognize.

Women were rarely honored in this way in ancient Rome, with public speech, much less recorded on a stele. Only two other eulogies to Roman women have survived, the Laudatio Murdiae , which is about the same time, and that of Emperor Hadrian to his mother-in-law Matidia.