More than 200,000 years ago, our ancestors stored bones for several weeks to eat the marrow during periods of lean hunting, new work reveals.

Until recently, it was thought that our Paleolithic ancestors were hunter-gatherers who lived from day to day... The reality would have been very different.

Our ancestors were far-sighted! Because 200,000 to 400,000 years ago in Israel, Paleolithic humans were already using natural "tin cans":deer bones, which retained their nutritious marrow for long weeks. These findings are based on nearly 82,000 bone fragments found in Qesem Cave and are published in the journal Science Advances .

Thousands of deer bones in a cave in Israel

Until recently, Paleolithic humans were thought to be hunter-gatherers who lived hand to mouth, consuming whatever they caught during the day and enduring long periods of hunger when food sources were scarce. But new work seems to show the opposite.

In the Qesem cave in Israel, researchers have looked at the remains of nearly 82,000 animals - mainly deer - bone fragments, most of which were no more than 2 cm. On these fragments, traces of scraping testified to the extraction of bone marrow, animal fat constituting an important source of calories. But was this marrow consumed directly or weeks after the death of the animal?

Our ancestors were far-sighted! Because 200,000 to 400,000 years ago in Israel, Paleolithic humans were already using natural "tin cans":deer bones, which retained their nutritious marrow for long weeks. These findings are based on nearly 82,000 bone fragments found in Qesem Cave and are published in the journal Science Advances .

Thousands of deer bones in a cave in Israel

Until recently, Paleolithic humans were thought to be hunter-gatherers who lived hand to mouth, consuming whatever they caught during the day and enduring long periods of hunger when food sources were scarce. But new work seems to show the opposite.

In Israel's Qesem Cave, researchers pored over the remains of nearly 82,000 animals - mostly fallow deer - bone fragments most of which were no larger than two centimeters. On these fragments, traces of scraping testified to the extraction of bone marrow, animal fat constituting an important source of calories. But was this marrow consumed directly or weeks after the death of the animal?

Dissection and removal of the tendon by the experimenter. Note the use of the tool with an inclination almost parallel to the bone. © Maite Arilla.

Bone marrow inside a bone stored for six weeks. © Dr. Ruth Blasco/AFTAU.

Up to nine weeks of preservation in autumn

To find out, the researchers measured the nutritional value of the bone marrow of contemporary deer recovered from a Spanish reserve, stored under different controlled environmental parameters (temperature, humidity). The bones thus underwent autumn, spring outdoors and spring indoors. As a result, seasonality is important in bone marrow degradation, with bone marrow remaining in good condition until week 9 in the fall scenario, but losing significant nutrient content after the 3rd week in spring scenarios. interiors and exteriors.

Marks characteristic of late marrow extraction

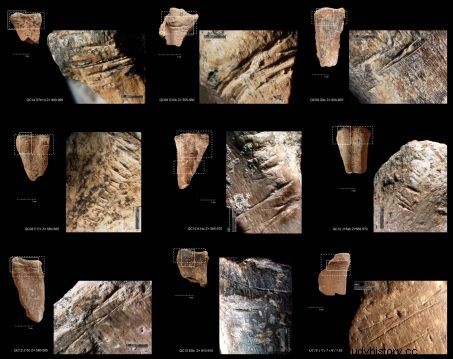

Each week, bones from each group were taken for the same individual to dismember and then extract the marrow, using flint and quartzite tools - compatible with the technological context and the rocks available at the cave of Qesem -, without specific instructions. They then observe that short incisions and saw marks predominate when the skin was removed after two weeks or more. "Since dry flesh is more attached to the bone, greater effort is required to remove it, leaving a distinct pattern of marks", specify the authors in the publication. Marks precisely present in nearly 80% of prehistoric bones:time had therefore passed between the death of the animal and the extraction of the marrow! "The bones were used as 'tin cans' which preserved the bone marrow for a long time, until it was time to remove the dry skin, break the bone and eat bone marrow ", emphasizes Professor Ron Barkai, who participated in the work.

Examples of cutmarks associated with disarticulation and/or peeling on deer metapodials from the Amudian and Yabrudian levels of Qesem Cave. © Ruth Blasco

Ancestors more talented than expected

"We show for the first time in our study that 420,000 to 200,000 years ago, prehistoric humans in Qesem Cave were sophisticated enough, intelligent enough, and talented enough to know that it was possible to preserve peculiar bones from animals under specific conditions and, if necessary, remove the skin, break the bone and eat the bone marrow ", adds Professor Avi Gopher, also involved in this work. This is the oldest proof in the world of the preservation of foods and their late consumption.

"It is possible that Neanderthal populations developed a technique for preserving perishable resources such as meat using sun-drying, smoking, or freezing ", and some examples have been found in France, dating from the Upper Middle Palaeolithic (between 10,000 and 250,000 years BC), explains to Sciences et Avenir Dr. Ruth Blasco, who led this work. But these signs remain complex to detect for paleontologists. "Nevertheless, I believe that Qesem will not be a unique case and that several sites will record this type of activity ", she concludes.

This discovery joins other evidence of innovative behaviors found in Qesem Cave, including recycling, regular use of fire, cooking and roasting of meat.