Hundreds of Polish scouts marching briskly in the shadow of Kilimanjaro on the occasion of the 3rd May holiday? This is not an imperialist's dream, but a real picture of a settlement in the Black Continent. Twenty thousand Polish women and men went to him.

When the news of the agreement between the London government and the Russians reached the Poles living in the USSR, a gigantic wave of them moved towards freedom. Men were drawn to the army, and in their footsteps were followed by women and children who wanted to free themselves from the hands of the Soviets as soon as possible:

The half-alive, shabby and sick women with children knew that sticking to the Polish Army was their only hope for survival. General Anders boldly decided, against Stalin's wishes, to take with the army as much of the Polish civilian population as possible across the Caspian Sea to Iran . (memory of Regina Villmo née Zielińska, collected as part of the "Trail of Hope" project).

Most of the fleeing Poles reached Iran. But that was by no means the final destination of their journey. After spending a few weeks in a transit camp, they were sent on their way.

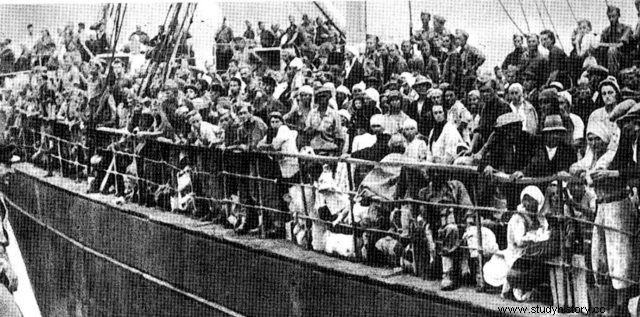

Ship transporting Polish refugees who left the USSR. 1942. (photo public domain)

The men who regained their strength set out to support British troops in this part of the world. There was a bigger problem with civilians. They were sent to the four corners of the world, to various provinces of the British Empire, over which the sun did not set. Nearly twenty thousand refugees ended up in the Black Continent , where for many years they had their own piece of Poland surrounded by the jungle.

Way into the unknown

There was a long way to go from the Middle East to Africa. First, a five-six-day cruise from Pakistani Karachi to Mombasa, and then an exhausting hike inland. As Danuta Skiba recalled years later:

Great camps for Polish civilians were built near Masindi. Their location [...] was chosen by the envoys of the Polish government in London and we were to stay there until the end of the war. We were assigned half a hut with only wooden beds on the bare ground. (Quote from:Norman Davies, "The Trail of Hope" Rosikoń press 2015).

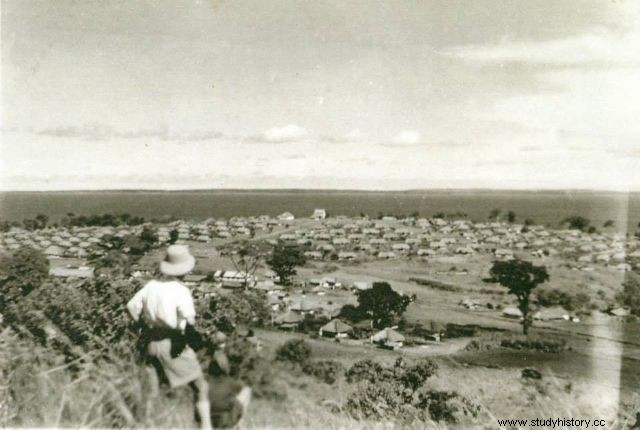

Ultimately, 22 housing estates were built, bringing together about twenty thousand Poles. Many of them had considerable doubts about what to expect in a foreign continent. They knew Africa mainly from "In Desert and Wilderness", and the image of the wild and inhospitable land emerging from the book must have filled them with anxiety.

High school students in the Polish settlement in Masindi, Western Uganda, 1944-1945. The photo is in the collection of the Kresy-Siberia Foundation.

The fear was fueled by rumors circulating around the camps. It was said that the British were doing everything they could to get rid of the "problem" of the refugees. Apparently, they sent them deliberately to countries with an extremely unfavorable climate, and then only waited for the same ones to die ...

Kowalski in the Black Land

The largest Polish settlement in Africa was Tengeru, located at the foot of Mount Meru, whose top is lost in the clouds. Also Kilimanjaro, with its famous snow-capped peak, is perfectly visible from there.

When the first transports of refugees reached their destination, the Poles found round mud huts covered with thatched roofs and native people clearing the bushes. A few or a dozen days earlier, there was a jungle there.

There were no special amenities waiting for the new residents. Houses with a diameter of five meters, due to their shape called by the locals hives, were able to accommodate three or four people. The British had to provide the Poles, who very often left the USSR only with their clothes on, with all the equipment. At the beginning, the settlers were given a bed, mattress, bedding, blanket, mosquito net, towel, cutlery, plates and cups. The cabins also had a table with chairs, a basin, a bucket and a lamp. Not much, but for people who broke free from Stalin's hell, it was still a luxury.

At the beginning, Poles did not even have to cook for themselves. There were general kitchens in the estate, feeding all residents to their heart's content. It was a wonderful change for many of those who were starving until recently. Only with time (and at the request of the interested parties themselves), the British commandant of the camp allowed them to cook on their own.

View of the Polish Koja estate in Uganda, 1945. The photo comes from the collection of the Center for the Documentation of Deportations, Expulsions and Resettlements.

An ordinary inhabitant of the estate had access to a church, synagogue and church (although this was not created immediately). There was a cinema and theater in the camp, as well as various clubs. The youth went to primary and secondary schools.

Poles could also receive, if necessary, medical assistance in a brick hospital. They went to nearby towns without any problems, where they spent the pocket money they received from the British.

Poland is not dead yet

In the very center of the Polish settlement in Tengeru, there was a hedge forming the inscription POLAND 1942, and Poles emphasized their patriotism at every step. State and church holidays were extremely important for the inhabitants of the estate, which turned into real manifestations of longing for the country.

Helena Kolowski, née Palimąka, who was born in the Kielce region in 1931 and came to Africa in 1943, recalled the Poles' approach to Christmas:

We celebrated public holidays, everything was the same as in Poland (quoted after:"Generations are leaving")

Children participating in the November 11 performance in Tengeru. Photo NN, the Polish Institute and the Gen. Sikorski in London.

Stanisława Giermer née Czerniak, born in the land of Nowogrodzka in 1930, recalled the great celebrations:

I don't remember exactly what occasion it was, but it seems that on May 3rd, we had a huge scout parade ... in uniforms throughout the camp ... maybe two hundred young people ... it was very solemn (quoted after:"Generations are leaving")

There were many orphans in the African camps, or children separated from their families and denationalized by the Soviet authorities. Also their guardians did not neglect to familiarize them with Polish culture.

The theater turned out to be an excellent tool for this. As Anna Hejczyk writes in the book "Siberians at Kilimanjaro":

The manager also took care of the patriotic upbringing of her charges. [...] Performances, folk dances, songs and regional costumes - all this influenced the consciousness of young people. The plays, often recreated by teachers from memory, were to convey important values to children and, above all, to teach patriotism and love for Polish culture.

Plaque on the wall of the Polish cemetery in Tengeru. (photo published under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license by Cezary Tulin).

Polish newspapers provided the inhabitants of the estates with news from Poland and around the world. The most important was "Pole in Africa", to which the supplements "Polish Book in Exile" and "Płomyczek Africanski" were added every two weeks. The latter, addressed to the youngest, provided them with contact with Polish literature for children and with their native fairy tales and legends.

In many cases, cultivating patriotism and instilling a love for Polish culture did not lead the refugees home. Many of those who found refuge in Africa did not return home - the death rate in the foreign climate was indeed frighteningly high.

At the end of the 1940s, the liquidation of Polish settlements began. Some of their inhabitants returned to the country, others, fearing repression by the communist authorities, chose to live in exile. Meanwhile, the Polish government was particularly vocal about the repatriation of orphans and claimed that they were in the British colonies against the law. After all, post-war reconstruction required a hand to work.

Today, the Polish settlements at the foot of Kilimanjaro are mainly cemeteries with the remains of those who will never return to their homeland.