Tens of millions of dead and even ten million people delivered into slavery - this is the balance sheet of three hundred years of colonial activity of this European country. An Empire Built on Corpses? Not exactly. The slave trade was not as profitable as it was thought ...

If Africa was indeed fashionable in London, it was also the cause of the lingering ethical crisis that would shape British foreign policy for the next half century. By the end of the 18th century, trade on Guinea's shores - which was then called after the country's most important commodities - ivory, gold, slaves, and grain - had become a key part of the economy. From the mid-century to 1772, the value of African trade increased sevenfold to almost a million pounds per year.

"How important is our trade with Africa," wrote an anonymous English merchant that year. "This is the first principle and the foundation of the rest of the principles, the most important driving force that sets all wheels in motion." The currency of much of the deal was people:the capturing of ships from London, Liverpool and Bristol exchanged firearms produced in Birmingham and East English textiles for slaves, which were sent to the liquidity of the British economy of tobacco and sugar plantations in the West Indies.

This is how Charlie English reports on the commercial activities of the British Empire in his latest historical report " The book smugglers from Timbuktu ". It was a nightmare for the people of Africa. Captured somewhere in the interior of the continent, they were dying out en masse on their way to the coast. Historian Joseph Miller in the book "Way of Death" calculated that about half of those transported died in this way. Perhaps a little more of them would live if they were caught by white people - who see them as a commodity that needs to be taken care of at least a little.

Meanwhile, the Africans were usually captured by the Africans themselves - members of other communities at odds with them (you can read more about it HERE). The brutality of these round-ups was inherent in the centuries-old tradition of permanent tribal warfare, and the profit itself was of secondary importance.

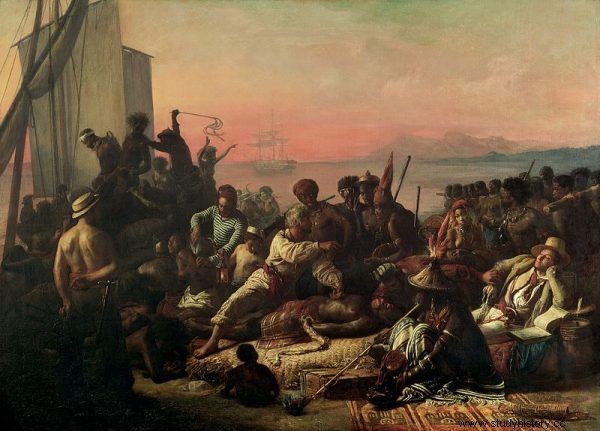

The slave trade in the Atlantic Ocean was started in the 16th century by the Portuguese. But it was the English who led the way in the transport of blacks from Africa to America. Pictured is François-Auguste Biard's painting "The Slave Trade".

Once the survivors reached the point of sale on the coast, first the blacks had to wait for the hold to be full - which again cost them a good percentage of their lives - and then spend several weeks below the ship's deck, in a closed and unventilated hold. In the 18th century, the death of a quarter of the "cargo" was considered an acceptable cost. Usually every seventh candidate for a slave died. In this way, from Africa to America, " in the 1860s, British ships transported 42,000 slaves a year across the Atlantic, more than any other European state ”- reports Charlie English.

Mass death statistics

Black slaves were first brought to Virginia (where English colonists established their settlement) in 1619. From that moment on, the economy and its laws were ruthless. Speaking its language, there has been a steady increase in both the number of the shipments themselves and their human content. Paul Johnson in his "History of the English" estimates that in 1768 alone, a total of 100,000 people were brought from Africa.

Of course, it wasn't just the English who did it - the French, Spaniards and Portuguese also grabbed and transported the living goods. However, it was English trade that accounted for well over 60% of all trade. These figures were roughly corroborated by the senior historian David Macauly Travelyan, who, writing about 1771, mentioned 53,000 slaves on 188 English ships departing from London, Bristol and Liverpool.

The years were certainly unequal in this respect, as were the proportions. Spain and Portugal gradually fell out of the game, and the farther into the eighteenth century, the more the entire burden of the global slave trade fell on the English. The number of 42,000 a year given by Charlie English is therefore averaged and mainly concerns the beginning of the second half of the 18th century. By 1807, they were delivering roughly 40,000 to 60,000 slaves a year to America, a total of around 10 million throughout Britain's colonial operation.

The article was inspired by the latest book by Charlie English "Smugglers of books from Timbuktu" (Poznań Publishing House 2018), in which the author interweaves the history of the African kingdom with the present, creating a story full of tensions.

The aforementioned Paul Johnson noted that "at the time of independence, slaves constituted a fifth of the American population." He forgot to add that after the United States gained freedom, the slave trade continued for a good thirty years, which was enough to bring an additional one and a half million people to the United States. And that, based on previous statistics, could mean another 7 million deaths.

Just right for an Englishman, not enough for England

Historians have usually considered the slave trade to be one of the most lucrative trading ventures of the 18th century. And even that it was he who was the engine of the English industrial revolution, the industrialization of the Isles, or more broadly - the imperial position of Great Britain at that time. This opinion was shared by almost everyone until economists started analyzing the phenomenon.

It turned out then that, yes, human trade allowed some to make small fortunes, influenced the prosperity of certain areas, but it was never so profitable as to significantly contribute to the economic development of the Empire. It is quite commonly assumed that the profitability of this business was similar to other branches of trade and provided the buyer with a profit of 10%. This number was strongly and longest undermined by historian Joseph E. Inikori, who suggested that in the calculations the selling price of slaves is underestimated and their mortality during transport is overestimated. After painstaking calculations, he also, in the end, admitted that even with a profitability of 40%, it would not translate significantly into the economy of the entire Kingdom .

Economic historian Stanley Lewis Engerman compared the profits from the human trade with the national income of Great Britain at the time, and he found that it accounted for an average of 1%, and 1.7% after 1770. "This should slow down a bit those who say that the slave trade was essential to the emergence of industrial capital during the industrial revolution," concluded the professor.

The trade in black people did not turn out to be as lucrative as the Europeans thought. So was it worth it? Pictured is a slave with scarring from whipping.

Roger Anstey was even more reserved and estimated the share of the profits from the slave trade in the rise of British capital to be no more than 0.11%. This is just right for an English corporation, but too little for England. The contemporary classic of economics, Adam Smith, rightly wrote about the economy based on slavery as completely ineffective. So why did the British empire deal with human trafficking for so long?

The turning point

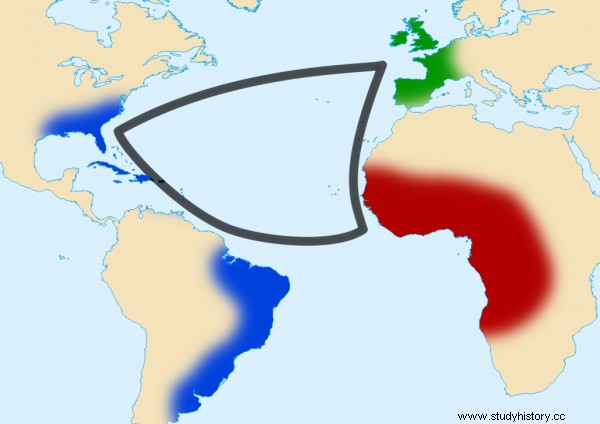

All this delayed genocide translated to some extent into the imperial economy. After all, the slave trade was not an isolated phenomenon, but was part of a series of financial and industrial phenomena, formerly known as "triangle trading", but today "the Atlantic system".

The ships, departing mainly from Liverpool, had cargo holds full of local cotton goods. In Africa, they were exchanged for slaves, and in America - these blacks were exchanged for cotton, which was delivered to factories near Liverpool. Of course not only that. Exclusive goods such as tea, coffee and sugar were also imported from America in such quantities that they soon ceased to be luxurious. During the reign of Charles II Stuart (died 1660), tea was drunk only by the elite, in special establishments offering culinary curiosities. A hundred years later, the historian Fryderyk Eden wrote:

Anyone who takes the trouble to come to the huts in Middlesex and Surrey at mealtimes will find that in poor families tea is not only a daily drink in the morning and evening, but that it is commonly drunk in large quantities also with dinner .

Diagram of the triangular trade in the modern era. Europeans transported various materials to Africa. Then they exchanged them for slaves, which were then transported to American plantations, from where they obtained goods for the European continent.

This trade exchange on three continents stimulated local centers in a natural way, created fashion (for example, cotton clothes replaced woolen ones in England) and created specializations aimed at satisfying them. The truth is, however, that if there is any benefit to the era of slavery at all, it was not money but thought .

It was at the end of the eighteenth century, partly on the wave of Enlightenment philosophy, but certainly also Puritan religious trends, that the idea of universal human freedom and - for the first time - the abolition of slavery appeared. British historian George Macaulay Travelyand calls this moment "a turning point in the history of the world" and thus develops this theme:

If slavery and the slave trade had continued throughout the nineteenth century, armed with new weapons of the industrial revolution and modern knowledge, the subtropics would have become a huge slave farm exploited by whites and European nations in their own countries would be decayed by the indispositions so characteristic of a civilization based on slave labor that perished the ancient Roman Empire .

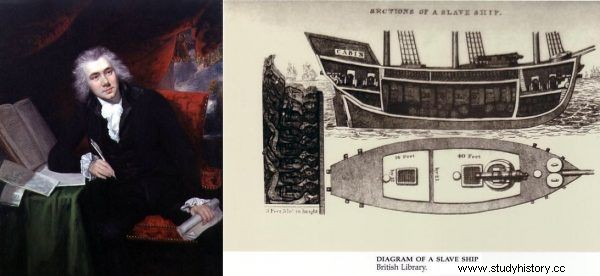

The historian speaks of the year 1807, when the abolitionist lobby, led by William Wilberforce, managed to push through the Slave Trade Ban Act, which directly led to the complete abolition of slavery in the Empire in 1833.

The article was inspired by the latest book by Charlie English "Smugglers of books from Timbuktu" (Poznań Publishing House 2018), in which the author interweaves the history of the African kingdom with the present, creating a story full of tensions.

The brutality of this practice has aroused serious resistance in society for at least a century. As Charlie English reports in a historical report, " Book smugglers from Timbuktu ":

(...) The British were slowly beginning to feel remorse. In the 70s. [Eighteenth century] 10,000 blacks worked in England on duty, and by the 1980s a small series of popular books had been published showing the detrimental effects of trade. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano in particular became a classic for anti-slavery Quaker activists who were to initiate the abolitionist movement. According to (...) members of the Saturday Club (...) finding other African goods offered a prospect of an end to the slave trade .

Wilberforce's task was therefore a bit easier, although it must be admitted that the methods he used were extremely modern; almost twentieth century. Namely, he started - of course on a scale appropriate to the then possibilities - a social campaign promoting abolitionism. As Travelyan continued:

The method by which this conversion was accomplished began by itself a new era in British public life. The anti-slave trade movement was the first successful modern type of propaganda, and its methods later found followers in the thousands of societies and leagues - political, religious, philanthropic and cultural - that characterized 19th century England .

William Wilberforce, one of the main opponents of the slave trade at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries (John Rising painting) on the left, slave transport ship from 1831 (Robert Walsh drawing) on the right.

A savage man too?

This is important, because despite the formal restrictions, the slave trade - although to a limited extent - continued. It must be remembered that the prohibition applied only to the territories of the Empire itself. Black people were still being sold to some Arab countries, the United States, and the Black African states, and no one controlled it in practice . The initiative in this matter came from the bottom up, such as in the case of - described by Charlie English - James Richardson.

Evangelical James Richardson joined the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society on the day it was founded in 1839 and became particularly interested in trade through the Sahara. In 1845, research led him to the Ghat Oasis in Fazzan, and on the way back he gave the Foreign Minister Lord Palmerstone the idea of a trip to Lake Chad. Its aim was to replace the slave trade with goods produced in Great Britain .

It is interesting, however, that all these initiatives concerned almost exclusively Africans and Africa - perhaps on the wave of Enlightenment philosophy and the idea of a "noble savage". The history of Great Britain did not record any major protests against the selling into slavery of the Irish, who were delivered to America in the 17th century by tens of thousands …

The remarkable history of the African kingdom, where the past is intertwined with the present: