When I was a kid, together with José Luis – my inseparable friend from the E.G.B.–, every Saturday we went to the public library. We got hold of that great volume with green covers and golden capital letters –Ancient Egypt – and we resumed our secret project:writing a book about archaeologists, wearing pith helmets, exploring among pyramids, sphinxes and pharaohs. Indeed, my love for archeology was born thanks to Egyptology. An attraction that, since then, I have never abandoned, nor will I abandon.

It is true that the passion for the past crossed paths, shortly after –it was the year 1982– with Charles R. Darwin. I had 13 blocks at the time and I decided that I wanted to dedicate myself to the study of the origin and evolution of Humanity. For this, it was necessary to travel to the African continent in search of the fossil remains of our most archaic ancestors and, not without many adventures and misadventures along the way, the dream came true with my first scientific expeditions in the Great Rift Fault . Working in the archaeological and paleontological sites of Lake Natron, in Tanzania –and as I had previously experienced in several European prehistoric settlements–, I verified that the work of the modern researcher is very far from that of the treasure hunters of until the middle of the 20th century. Even having replaced the pith helmet of childhood dreams with the fedora, the current archaeologist and anthropologist is light years away from the methodology used by those adventurers on whom George Lucas based himself to build the character of Indiana Jones, the Hiram Binghams, Roy Chapman Andrews, Belzoni and etcetera.

Today, the detective of the past does not dig big holes nor does it destroy funerary complexes in search of beautiful and valuable objects destined for private collections or sumptuous colonial museums. No, the contemporary investigator follows protocols much closer to another of my heroes:Sherlock Holmes. Every little fossil or piece of evidence is important. That is why, paraphrasing the words of Holmes in A Study in Scarlet, just as from a simple drop of water we can infer –through the science of deduction– the existence of an ocean, by looking at bone fragments, analyzing the microscopic traces of use on a stone knife or measuring the disposition of all the fossil remains of an occupation ground can lead us to recreate a scene that occurred millions or thousands of years ago. This was one of the great contributions of prehistory and paleontology to the New Archaeology. But at the beginning of the 20th century, and going back to the romanticism of archeology in Egypt, there was a man who was ahead of his time. An enthusiast whom I have always admired thanks to those unforgettable Saturday readings:Howard Carter.

Just as the Frenchman Champollion, precisely in the Napoleonic era, imagined visiting Egypt and would make it a reality –in addition to deciphering the Rosetta Stone–, from the Sant Jordi library –in the working-class neighborhoods of L'Hospitalet– I wanted to go to the land of the Nile to see the place that made a clever English Egyptologist famous. Deprived of money and social position, Carter struggled until he obtained the providential financing of Lord Carnarvon. Thus, with tenacity and method, in 1922 he discovered the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Another, in true Dr. Jones fashion, would have impatiently waded into the Valley of the Kings hypogeum like an elephant into a china shop, but he was different. He acted more like the unflappable detective from 221b Baker Street. The tomb being almost intact and full of treasures, he did not allow himself to be blinded by the gold that surrounded him –“I see wonders”, he told Carnarvon when he saw the interior through a small hole– and began a meticulous work of prospecting, cleaning, excavating , restoration, drawing, photography, written documentation, inventory and detailed study of all objects:from the famous funerary mask of the young pharaoh Tutankhamun to the last tiny necklace bead abandoned on the ground.

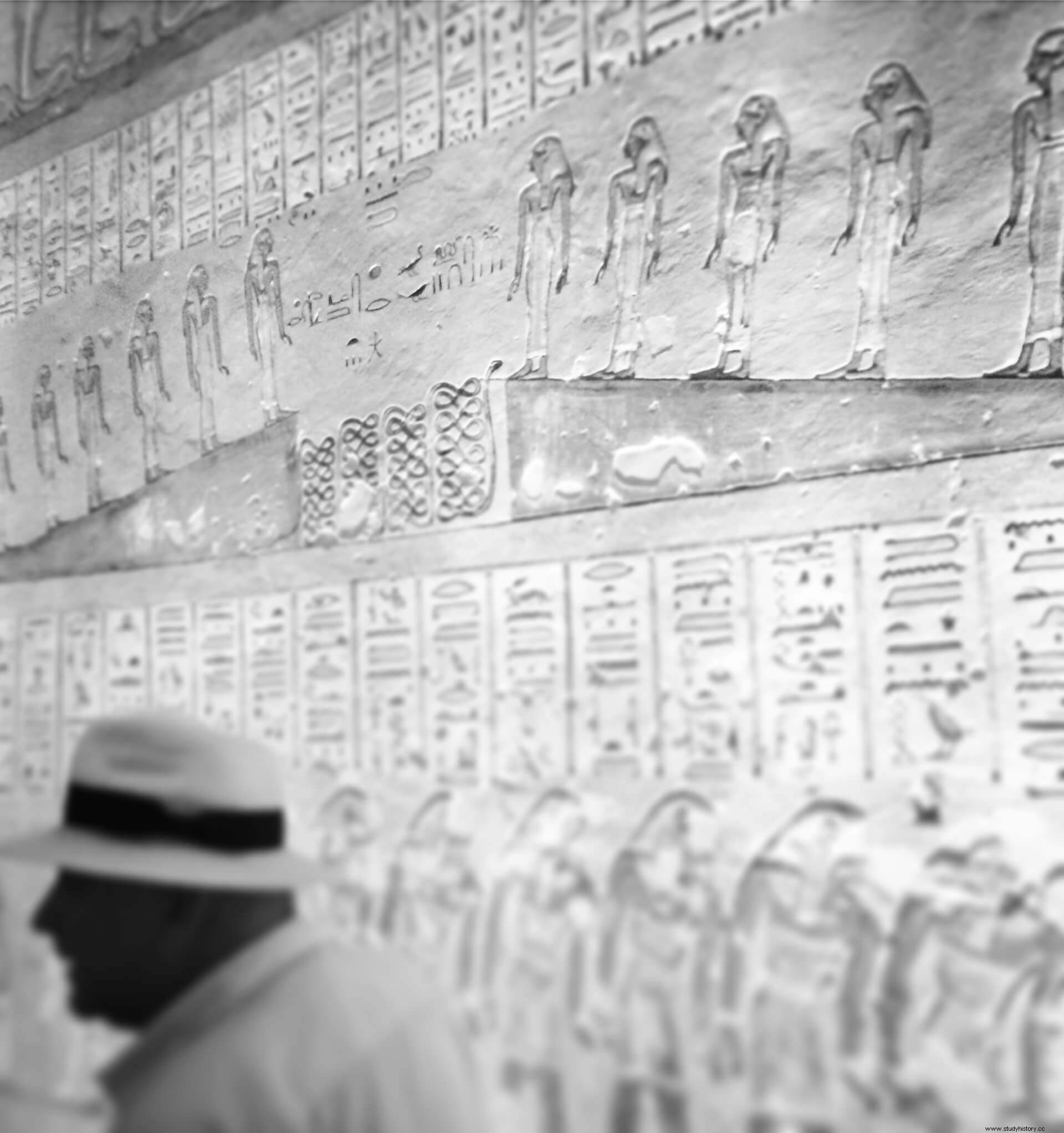

That is why every time I find myself in Luxor , standing on the first step of the entrance to KV62, always peering into the shadows with a mustache and white hat… it's just to say thank you to Professor Carter. That said, deep down I'm a romantic primate.

Jordi Serrallonga

Archaeologist, naturalist and explorer

Professor at the Open University of Catalonia

Collaborator of the Museum of Natural Sciences of Barcelona

Author of Awake Ferro