When Herodotus , in the 5th century BC. C., he undertook the task of describing Egypt in the Histories of him , a certain topic in particular fascinated him, and so he stopped to write a long, detailed and explicit study on the different types of mummification and its techniques (II.85-90). Beyond the Greek taste for anecdotes, the inclusion of such a macabre and specific subject responded to deeper motivations, which have to do with the Hellenic vision of the world itself:Egypt was represented as an ancient and developed civilization, with arcane knowledge and profound religiosity, but also strange and mysterious, with extravagant customs. Nothing exemplified this ambivalent vision better than the mummies and their details.

Eternal Myth

Herodotus's work became a true reference manual for all Greco-Latin writers regarding Egyptian culture. Of course, the vision of this civilization in the ancient sources was very varied and was conditioned by multiple ideological motivations:from the melancholic fascination of classical Greece, which saw Egypt as a utopian country, to the animosity promoted by Augustus, annoyed at Cleopatra's challenge . The interesting thing is that, beyond the changing attitude of classical literature, certain basic ideas remained intact:its immutability in time, its hidden wisdom, its deep religiosity and its mysterious funerary customs, which became the dogma that will define Egypt by transmitting itself to Western culture.

Probably one of the most persistent consequences of that image is its constant association with a multitude of mystical and esoteric movements, a mixture of magic, astrology, philosophy and religion. Emerged during the Greek domain, the Ptolemaic period, and extended with the Roman Empire, they responded to the efforts to understand that mysterious Egyptian spirituality and access their supposed lost knowledge. The hermeticism It is probably the best known and most sophisticated but, in general, virtually everything related to the occult sought its references in the country of the Nile . This obsession had a long continuity over time, remained in medieval alchemy and astrology, both Latin and Arabic, and experienced a new boom in the Renaissance, capturing famous humanists such as Athanasio Kircher or Giordano Bruno. Always standing on the thin edge between Christian adaptation and heresy, not even the dissuasive Catholic bonfires put an end to those concerns; the tireless search for the hidden keys of Egypt would be transmitted to Freemasonry, Nazi esotericism and the most superficial astrological trickery. That mirage will fill with allusions The Magic Flute of Mozart and will populate dollar bills with pyramids.

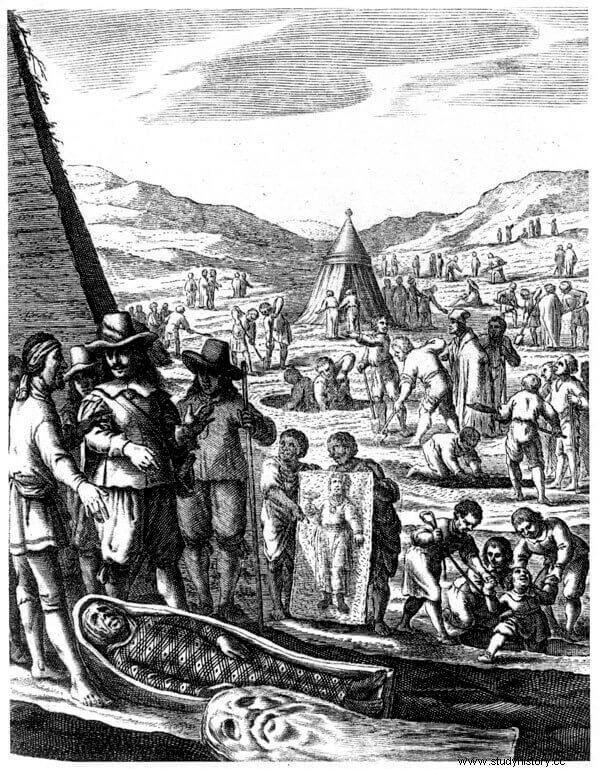

Of course, mummies were not excluded from such occult interest by the Egyptians. Quite the contrary, as part of the idea that they harbored arcane scientific knowledge, the legend spread that embalming substances had supernatural medical properties. This led to the spread of the practice of crushing mummies since the Middle Ages in order to use the resulting powder in healing elixirs (mummia ). Its popularization, which reached the apothecaries of the European monarchies, led to the development of a whole normalized market of mummies, with the consequent systematic looting of tombs, as well as their falsification through the arrangement of recent corpses.

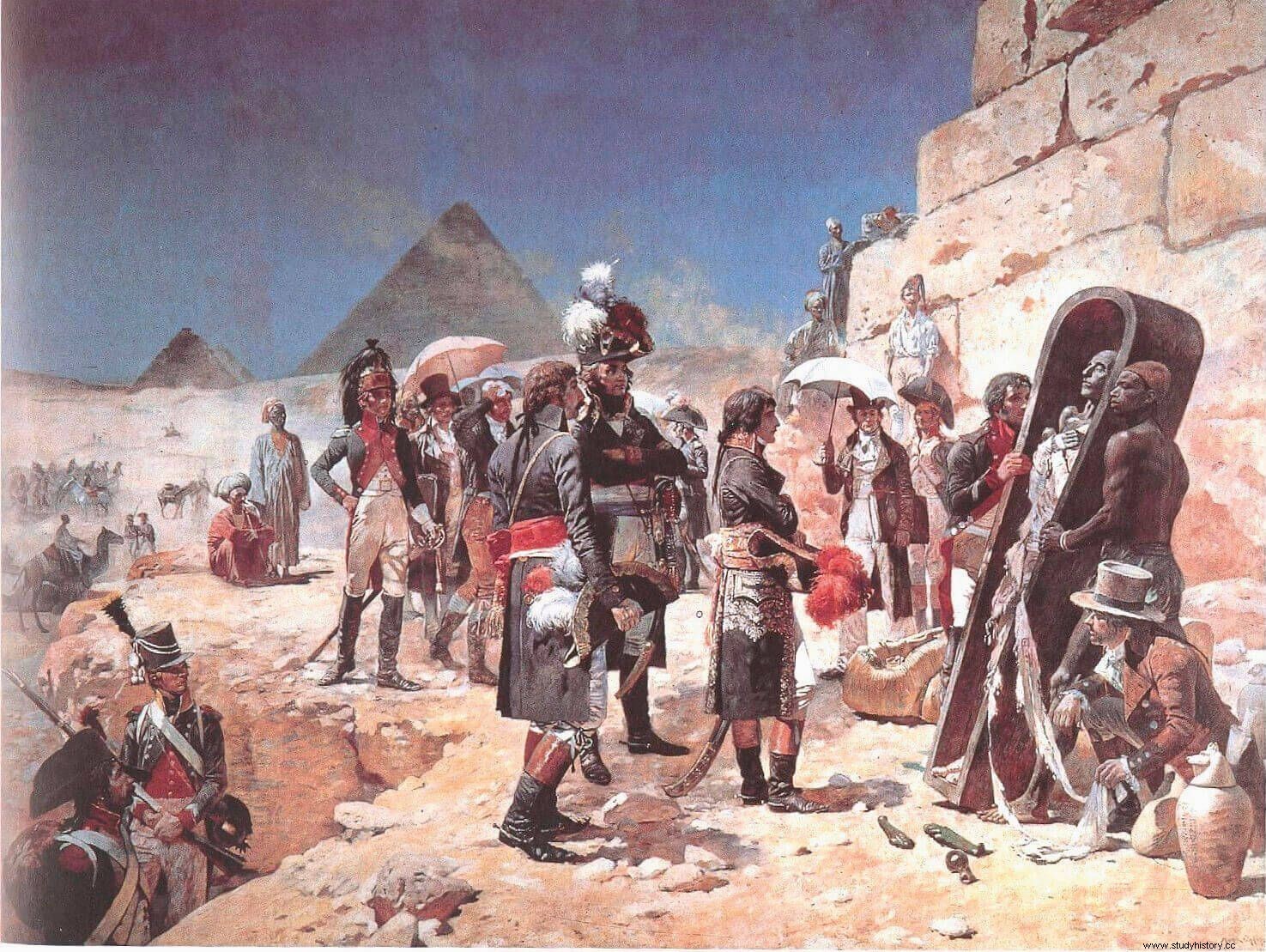

Meanwhile, knowledge about Egyptian culture was becoming more and more palpable and direct. There have always been pilgrims, merchants, travelers and antique dealers who dared to enter the country and its famous monuments, but without a doubt the doors of Egypt were definitively opened with Napoleon's campaign in 1798 . With it, his systematic exploration and plundering began, which marked the beginning of his archaeological and philological study and, ultimately, the birth of Egyptology as a discipline. It also meant a new "democratization" of the myth:the colossal statues, mummies, sarcophagi and trousseaus, hitherto accessible to a few scholars, could now be seen in the new Western museums, to the enjoyment of all of society and satisfaction of imperialist pride. With these new opportunities, the heroic figure of the archaeologist explorer was also born:adventurers halfway between academics and thieves who embarked on the profitable activity of searching temples and tombs in search of valuable pieces. This is the case of Giovanni Battista Belzoni, a circus giant turned professional looter, who became world famous for entering the pyramid of Khafre in 1818, which was celebrated with books, conferences, exhibitions and commemorative medals.

But that physical rediscovery of Egypt did not dim its halo of mystery; on the contrary, it gave it a new life. Lucubrations about its secrets spread to a bourgeois and educated society avid for curiosities, also incited by a new mass cultural, publishing and tourist industry that would make a good profit from it. That nineteenth-century society excited by the exotic, anxious to escape from its restrictive reality and fascinated by everything that transgressed its spiritual and moral taboos, welcomed the enigma that Egypt offered them with open arms.

A good example of that combination of science and entertainment it is the phenomenon of “mummy unrolling”. When an amateur managed to get his hands on a mummy in the antiques market, he would hire a "professional" to ceremoniously open it at a public event and reveal its secrets. He thus satisfied the morbid curiosity of the guests about the state of conservation of the body and the jewels that adorned it. The practice became remarkably popular among the wealthy classes, with some of those specialists, such as Thomas "Mummy" Pettigrew, becoming true celebrities.

At the same time, mummies invaded literature. The futuristic story of Jane Webb Loudon, The Mummy. A Tale of 22nd Century , from 1827, is generally considered the first work in history about a living mummy. From that moment on, the stories, novels and plays with this theme followed one another unstoppably, seducing great figures such as Edgar Alan Poe, Louisa May Alcott or Bram Stoker, among many others. Ancient Egyptian occultism thus intermingled with the romantic taste for monsters, death, the supernatural, and impossible erotic romances.

In this way, throughout the 19th century, in parallel with the development of Egyptology, Egyptomania was born, the popular recreation of Egyptian culture and its topics. It was very present in literature, but also in art –such as in the exceptionally documented painting by Lawrence Alma Tadema–, music –such as the famous Aida by Verdi (1871)– or architecture –such as the famous Egyptian Hall in London or, of course, countless pantheons and funeral decorations–.

If Napoleon's campaign opened the doors of Egypt to the West, the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb by Howard Carter in 1922 He fully introduced him to the new reality of the 20th century. An unprecedented, perfectly designed media apparatus was deployed around the event, making the most of new technological resources to magnify the discovery and its protagonist. Paradoxically, all these novelties did nothing but relaunch the topical image of Egypt as a culture defined by the Beyond and its mysteries. The episode not only reproduced the stereotype of the explorer, the tomb, the mummy and the treasure, but it was also imbued with fantasy overtones. Indeed, the discovery of Tutankhamun is inseparably linked to the legend of his curse; propagated after the death – nothing supernatural – of Lord Carnarvon, the controversy reached unimaginable heights, fueled by the sensationalist press and with the intervention of celebrities such as Arthur Conan Doyle. The story of this archaeological find thus acquired the form of a hackneyed fictional plot, but with the help of a new journalistic projection and the added value of dangerously intermingling with reality.

Not by chance, in the heat of the Carter episode, the mummies made the leap from literature to cinema with The Mummy (1932). Although there were already some silent films with this theme, the overwhelming success of this film consolidated a subgenre that would be enormously prolific, reinvented again and again, whether in the tone of a thriller, adventure, horror, comedy, eroticism or children's entertainment. Its vitality is demonstrated by the repercussion of the recent Stephen Sommers saga (1998-2008), which has generated a colossal merchandising franchise. , TV shows, novelizations, animated series, video games, etc. But it is not only a cinematographic phenomenon; In the current imaginary, the Egyptian mummy is already a universal archetype, a standard monster, like vampires, skeletons or Frankenstein's creature, and it is absolutely omnipresent. Egyptomania (with tutmania and mummymania) ceased to be the fashion of a boring bourgeoisie to become a global cultural phenomenon. Herodotus would smile with satisfaction.

A double-edged sword

There is no doubt that Carter's discovery, beyond its fanciful aspects, constituted a true turning point in the history of Egyptology as discipline. But it was not so because of the historical information provided by the find (which was minimal) or the value of the objects found; he made a difference because, far from conveying a more serious image of Egyptian archaeology, he reinforced the topics forged centuries ago and favored their association with scientific research itself. Above all, his media paraphernalia consolidated the prototype of the heroic archaeologist:the adventurer with unique abilities who, after overcoming adversity, manages to reveal to the world a universal secret or a spectacular treasure hidden under the desert sands. That model has captured the collective imagination, reproducing itself repeatedly in popular culture; it is in Indiana Jones, in Rick O'Connell, in Lara Croft and in hundreds of characters that respond to an identical pattern. But the most important thing is that this stereotype was also linked to the Egyptologists themselves, becoming the ideal with which they are forced to compete with society.

Undoubtedly the most transcendental effect of Egyptomania is its decisive influence on Egyptology . On the one hand, it is true that this enormous popularity has very positive effects for research:no other archaeological specialty has so much repercussion in the media, sells so many books and inspires so many documentaries, which in turn provides –in principle– more opportunities for financing and greater social recognition, as well as the attraction of students in universities and the public in museums and monuments. However, these advantages come at a price.

First of all, you pay on the quality of the popularization of Egyptology itself. To begin with, the attraction exerted by the subject has the effect of generating an amateur movement unparalleled in any other discipline. The involvement of amateurs, better or worse trained, in informative work is systematic and inevitable, which favors its dissemination, but often also contributes to repeating topics or, in the worst cases, feeding grotesque theories (the so-called "pyramidiotes"). ”). On the other hand, the very economic exploitation of Egyptology entails in itself a popularization of its knowledge. Much is published and produced on the subject and, by its own commercial logic, it is done as quickly and cheaply as possible. This dynamic means that imprecise knowledge tends to be transmitted and that, in addition, the themes that are most attractive and recognizable to the general public are reproduced:mystery, religion, famous people and, obviously, tombs and mummies.

Now, what role do Egyptologists play in this? Many researchers critical of their own discipline warn of how the academic world itself is unconsciously feeding these preconceived images. The key is in the fact that the research largely depends on the popularity that Egypt enjoys:for an Egyptological team to obtain funding and institutional support What you need has to respond to certain preconceived expectations, basically, finding a new tomb, valuable pieces or the mummy of a historical figure, that is, what society expects from a discovery in Egypt. Or put another way, a material that can be translated into reports, exhibitions and merchandising in a simple, fast and profitable way.

This conditions the type of archaeological projects that are designed , and with it, the topics covered:the excavation of the tomb of a member of royalty or a high official has infinitely greater media potential than the excavation of, say, a peasant village, although the latter could tell us much more about the way of life of the vast majority of the inhabitants of Egypt. Indeed, an important part of the research continues to focus on very traditional issues:religion, the funerary world and the pharaonic court. On the contrary, other alternative topics, although increasingly discussed, continue to be a minority :social conflicts, economy, landscape archaeology, urban planning, etc., issues that are considered fundamental in other areas such as Greece or Rome. The result is that, in general, Egyptology has a certain tendency to isolate itself, maintain traditional perspectives and focus excessively on funerary archeology and the study of elites. This in turn has consequences for exhibitions and museums. In any conventional exhibition on Egypt, the question of the afterlife has a leading role, if not an exclusive one; In addition, it is usually presented with a dark and suggestive set design, and all its technological resources are poured into 3D representations of mummies or audiovisuals on mummification. In short, what is expected to be found is sought and what is expected to be seen is taught. And with this, the topic of the Egyptian obsession with death continues to be transferred to society, leaving aside many other interesting facets of its history.

In this way, the popularity of the topic and the attention of the media turns out to be a double-edged sword. Actually, these problems are not exclusive to Egyptology, they affect all the specialties of archeology today; however, the case of Egypt is particular because the strength of its myth is incomparably greater than that of any other civilization. This translates into the frustration of researchers, disseminators and conservatives, who have to work in a world very conditioned by preconceived ideas. True Egyptologists face the challenge of questioning these topics and transmitting it to the people.> They take on the challenge of discarding the image of Egypt as a dehumanized civilization, in which mummies seem to have more life than the society that created them.

Bibliography

- Carruthers, W. (2015) (ed.):Histories of Egyptology:interdisciplinary measures . London-New York:Routledge.

- MacDonald, S.; Rice, M. (2003):Consuming Ancient Egypt . London-Portland:University College London Press.

- Pérez Largacha, A.; Gómez Espelosín, F. J. (2003):Egyptomania:the myth of Egypt from the Greeks to us . Madrid:Alliance.