If there is something that characterizes archeology, it is the care, the almost exquisite touch that is given to the sites and that makes a tool as simple and limited as a brush the protagonist of the excavations, making the archaeologist have to spend hours and hours under the sun separating just a few centimeters of sand or earth to ensure that no piece, no matter how small, escapes. Thus, reality contrasts with the fantastic image left by the cinema and the adventure is more in the process of discovery, slow as it may be, than in the action. But it was not always like this; In its beginnings, archeology sought to exhume remains of other civilizations at all costs and things were done without so many trifles. A good example of this was Giuseppe Ferlini.

Let us place ourselves chronologically in the first half of the 19th century, the time in which Archeology was born as an auxiliary science of History. Of course, Man had always been interested in his past and the ancient chroniclers already paid attention to earlier times to explain his present. However, it was not until the Renaissance that a revival of Classical Antiquity was experienced through the recovery -and imitation- of its art; We know that Brunelleschi, Michelangelo or Domenico Fontana attended those Roman excavations, the result of which came to light the famous sculptural group Laocoon and his sons , as well as the ruins of Pompeii, among others.

In the following centuries, that taste for the past became established, although from a rather collector's point of view. The city buried by Vesuvius was rediscovered after Johann Joachin Winckelmann found Herculaneum and went down in history as the father of Archaeology. The ban had been opened, everyone set out to dig the earth in search of treasures, Napoleon carried out his Egyptian campaign taking with him a scientific team and the so-called cabinets of curiosities began to appear. It is in this context, in which the passion for Egypt had become fashionable, jumping from France to England and other countries, that Ferlini should be placed.

He was born in Bologna in 1797 but soon left his house fleeing the impossible coexistence with his stepmother. He passed through the cities of Venice and Corfu, in some of which he studied medicine, although he said that he had already begun his studies before. The fact is that, giving boats, in 1817 we find him in Albania, a country that was then part of the Ottoman Empire but, being in conflict with the sultan, welcomed anyone in his army. If in addition he was a doctor better than better and, in any case, nobody demanded the title from Ferlini.

In any case, five years later he is part of the Greek rebels who were facing the Turks in the Peloponnese peninsula. Defeated by the enemy troops of Ibrahim Pasha, son of the governor of Egypt Mehmet Ali, who won resounding victories like that of Mesolongi, Ferlini had to escape once more and did not return to Greek territory until 1827, although he did so rather to bury her lover By then the war was ending, since the three great European powers (Russia, France and the United Kingdom) had decided to intervene and consolidate, thanks to the naval victory in Navarino, what had been baptized as the First Hellenic Republic.

Ferlini decided to gather his savings and emigrate once more. The destination this time was Egypt, which appealed to him for two reasons. The first, that a good part of the troops stationed in Greece by the Ottoman Empire were Egyptian and now they were preparing to re-embark back to their land, presenting themselves with a good opportunity to find a place on one of the ships; the second, that Mehmet Ali was determined to modernize his administration and, consequently, hired European technicians. A doctor would be welcome.

Effectively. the Italian landed in Alexandria in 1829, heading for Cairo. One of the things that the governor wanted to improve was the army and that included providing it with more efficient military healthcare, so Ferlini enlisted as an assistant and the following year he was already a senior doctor in an infantry battalion. As such he accompanied the I Regiment on its march to Sennar, the capital of the homonymous sultanate, where that body had been assigned. Sennar was located in southeastern Sudan, on the banks of the Blue Nile, as Mehmet Ali's campaigns had extended the borders to Ethiopia.

The trip lasted more than five months and during that time Ferlini visited places like Khartum or Wadi Halfa, where there was an abundance of archaeological remains, raising in him his first interest in ancient civilizations. In fact, after a dark stage in which he married an Ethiopian slave, lost the son he had with her and was forced to fight a malaria epidemic in a hospital with poor facilities and harsh conditions, he was transferred to Khartum to join a medical team. There everything was more bearable and he also made friends with the governor, Curschid, whom he accompanied on several expeditions through Nubia in search of gold.

Surely the scarcity of found metal prompted the Italian to look for an alternative:the pharaohs had accumulated a lot in their heyday; you just had to locate it and dig it up. In fact, it had precedents:in that first quarter of the 19th century, the Frenchman Bernardino Drovetti, the Paduan Giovanni Batista Belzoni and the Englishman Henry Salt had taken the first serious steps in Egyptology precisely at the service of Mehmet Ali. Ferlini chose Meroe as his objective, the city of the Meroitic Kingdom that had provided Ancient Egypt with its black dynasties, and he went there on an expedition associated with the Albanian merchant Antonio Stefani, who financed the equipment in exchange for half of the profits obtained. .

The column, made up of the two of them plus his wives, around thirty servants, hundreds of porters and a good number of horses and dromedaries, set out in August 1834. The results of that adventure were not good. First, they attempted to access a half-buried temple but to no avail, despite chipping away at the walls to open an entrance. Then they also failed with some sand-covered ruins where they found a large obelisk decorated with hieroglyphics but which, due to its enormous size, had to be left behind. Meanwhile, diseases began to take their toll on workers and animals.

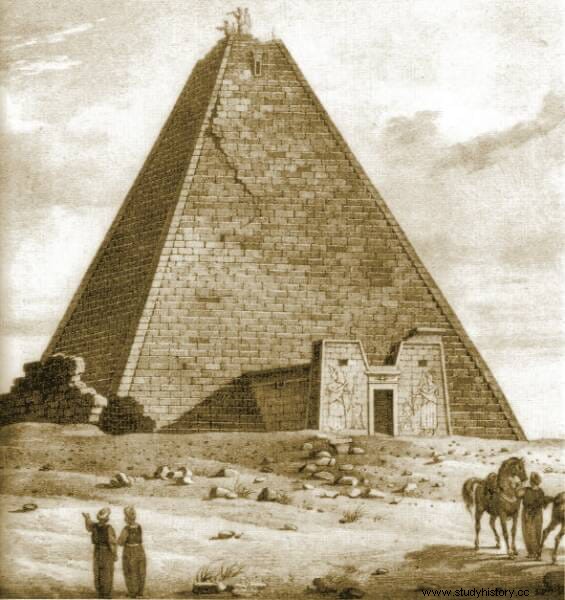

Things were starting to get difficult and Ferlini decided to try his luck with the pyramids. Not the Egyptian ones properly speaking, but those of Meroe, where there are more than a hundred, although they are much smaller than the others - none exceed thirty meters in height - and, on the other hand, they have a considerably greater angle. They had been discovered in the previous decade by the Frenchman Frédéric Cailliaud, also in the service of Mehmet Ali and also while looking for gold, since the local tribes had a legend about it, hence Ferlini wanted to try as a last resort. He specifically focused on the forty-seven of Es-Sour and this time he did not walk with contemplations:he hired half a thousand indigenous laborers who, with their picks, dedicated themselves to demolishing them. That irreparable damage was in vain.

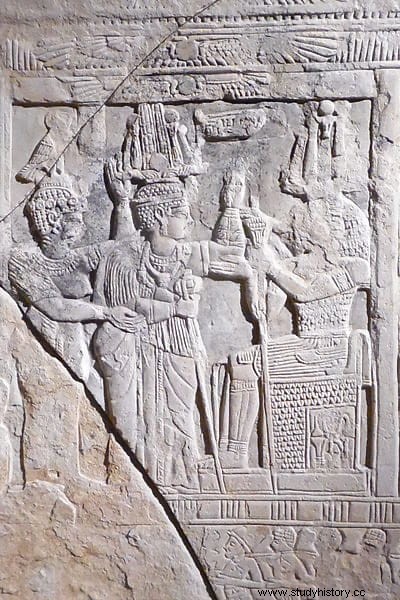

Already desperate, the Bolognese chose the largest pyramid, the one known today as N6, and instead of cutting it laterally, he did it from the top down. This time he smiled fortune and a sarcophagus appeared -without a mummy- accompanied by a funerary trousseau. Not that it was wonderful, but it certainly corresponded to a real person (today identified as Queen Amanishajeto, who ruled on horseback between 15 BC and 1 AD) and it was suggestive enough to suppose that there could be more. And so it was because two weeks later a secret chamber beautifully decorated and with some interesting objects appeared; almost all of them were bronze, rather than gold, but at least they wouldn't come back empty-handed. Of course, it was necessary to keep the pieces hidden when doubting the fidelity of the natives, who flocked to the excavations when they found out that there had been finds.

Finally, the servants alerted Ferlini and Stefani of a betrayal and together they loaded what they found on their camels:a dozen gold, silver and bronze bracelets, sixteen gold scarabs with enamels, dozens of rings, bracelets, crosses, necklaces, figurines of various stones... They managed to reach the Nile, embarking and putting distance in between. They went down the river to the Fifth Cataract and then the Bolognese went to Cairo to present his report to the governor. Said report or an enlarged and detailed version, he published later, in 1836, when he had returned to his native city; his title was Nell’interno dell’Africa 1829-1835 .

That treasure was distributed throughout Europe between sales, donations and auctions to try to recover what was invested; most of it was divided between the Egyptian museums in Berlin and Munich, since it was validated by the German Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius, against the experts of the British Museum, who considered it false and, consequently, did not want any piece.

Ferlini died in Bologna at the end of 1870 and was buried in the cemetery of the Carthusian monastery of Certosa di Bologna, where the remains of other personalities lie, such as the singer Farinelli, the automobile manufacturers Alfieri Maserati and Ferrucio Lamborghini, Letizia Murat (the daughter of the famous Napoleonic Marshal) or Isabella Colbran (wife of the composer Rossini). Today he is hardly remembered except for having destroyed forty pyramids.