If we talk about a famous wall built in Great Britain to block the way to enemies, inevitably Hadrian's Wall, erected in the 2nd century AD, comes to mind. in order to defend against Pictish incursions. Someone may also remember the Wall of Antonino Pio, two decades later. But there was a third wall -not Roman but medieval- that in 2010 was presented to UNESCO to be incorporated into the World Heritage Site, although it did not succeed:the one known as Offa's Dyke .

Joking a bit, we could say that Donald Trump is a faithful student of History when he proposes to build a wall that prevents Latin American immigrants from entering the US, since there are a few examples of that system of blocking foreigners if we look back:the one built by Israel in the West Bank, the one built by Morocco in the Sahara, the famous Berlin Wall (which in this case was to prevent leaving), the Croatian walls of Ston (Croatia), the famous Chinese Wall...

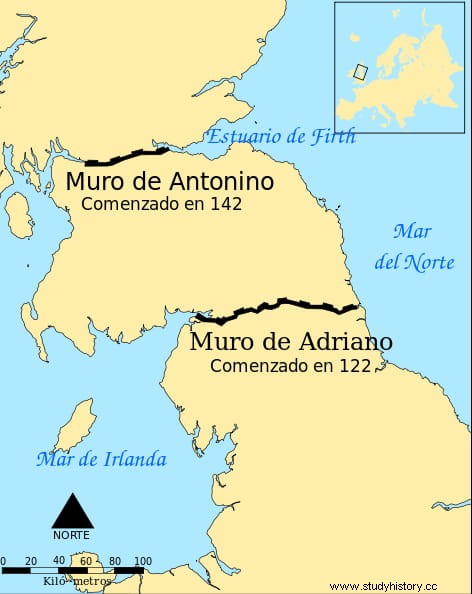

If most of the cases cited extend over very vast territories (apart from the 21,000 Chinese kilometers, the Moroccan wall reaches another 2,720, for example), they would make more sense in Great Britain, where they were also favored by a less abrupt relief. Thus, Hadrian's Wall measured about 117 kilometers from the Gulf of Solway to the estuary of the River Tyne, dividing the island into two halves. That of Antonino Pío, parallel to the previous one, reached 160 kilometers and left the limes already in Caledonia (Scotland).

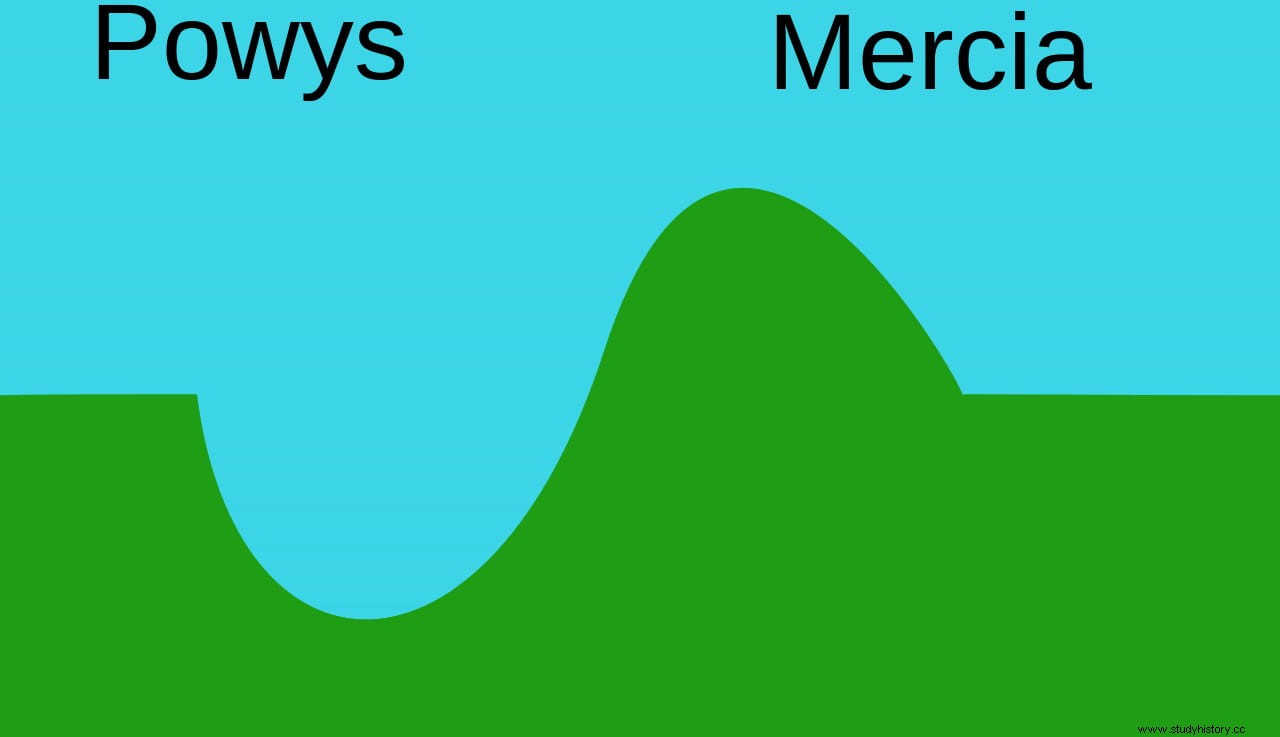

But the Offa's Dyke had different characteristics. First, because stone was not used in its construction, but adobe. Second, because the Romans did not do it, but the kingdom of Mercia, one of those that formed the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy in the 8th century together with Essex, Northumbria, Wessex, Sussex, Kent and East Anglia. And third, because instead of running from east to west, it ran from north to south, establishing the Mercian border with the Welsh kingdom of Powys, which was not Anglo-Saxon but British, of Celtic origin.

It was about 150 miles long by 12 miles wide and 1.5 miles high, stretching from Liverpool Bay to the Severn Estuary, with the Mercian domains to the east and the Welsh to the west. A convenient separation because, according to the writer and traveler George Borrow in his Wild Wales (an account of his journey through Wales in 1854 including folk and historical as well as geographical aspects, published in 1862):

Powerful reasons to make the boundaries clear, no doubt, and in fact the current border follows a similar path. However, this demarcation was not by mutual agreement. The remains of the wall show that it had a moat on the western side, indicating that it was built as a defensive system, presumably against Welsh raids.

The name means Offa's Wall, alluding to the Mercian monarch who promoted its construction between 757 and 796 AD. He was an important character, not only because he wore the crown but also because he introduced the penny as currency. But above all, for leading his kingdom to dominate most of southern England south of the Humber River, to the point that he became known as Rex Anglorum (King of the Angles), which was almost as much as to say of all the English; something remarkable if we take into account that the unification of the country would not take place until the 10th century. Also, he maintained diplomatic relations with Charlemagne (both negotiated the marriage of his children, although without success).

Offa did battle with the Welsh at Hereford in 760 and undertook further campaigns against them in 778, 784 and 796. Limited evidence makes his reign difficult to ascertain but he must have been powerful enough to marshal the necessary resources. and the labor required to build the wall. In this sense, the workers, serfs, probably had to submit to a compulsory and free labor benefit, typical of feudalism, called corvea.

Now, one thing is that the wall bears the name of Offa and he is considered its author and another that this is true. This is what was traditionally thought, but the radiocarbon analyzes carried out in 1999 on some soil samples suggest that it may be an earlier work than previously believed, at least in part, considerably advancing the date:to the year 446 AD. New analyzes carried out in 2014 in other areas also gave very early results, between the years 541 and 651, the oldest of all being from 430.

In fact, some researchers consider that the description that the Roman historian Eutropius left around 369 AD. of the wall of Septimius Severus (which in reality is not such but rather reinforcement work on Antoninus Pius) in his work Historiae Romanae Breviarium would actually correspond to the original phase of the Offa’s Dyke . Most archaeologists disagree because that would advance the dating even further (Severus' period was from 193 to 211). It does seem reasonable that when Bede the Venerable (who lived between the 7th and 8th centuries) speaks of Severus' Wall in his Ecclesiastical history of the people of the Anglos he actually refers to Offa's, since he says it was made of earth, not stone, crowned by a wooden palisade and with a moat.

In any case, how to explain such an early chronology? There are two possibilities:one, that the Romans already built something there; and two, that the rest would surely be the initiative of successive Mercian kings, not just Offa. Which leads to the question why the wall is then attributed to that monarch. Until now, historiographical sources were used to date it and explain its historical context. The main one is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , from the 10th century, which has the problem that there are several manuscript copies and discordant in some places.

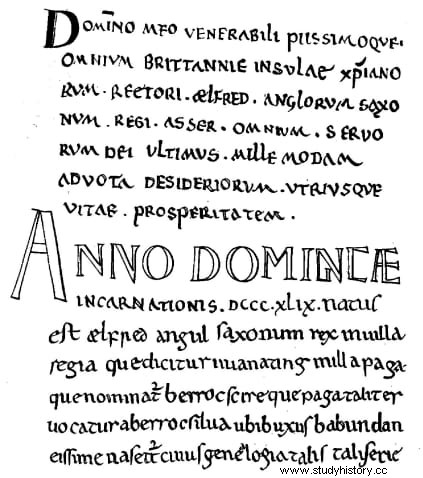

But who attributed the wall to Offa was John Asser, a Welsh monk who lived in the second half of the 9th century and worked as a translator at the court of Alfred the Great of Wessex to, already at the end of that century, become bishop of Sherborne. Asser wrote one of the fundamental works to understand the monarch's reign, Life of King Alfred (which he later expanded with an annex on the history of England) and in it he attributes the wall to Offa:

Since the fifties of the last century, historians such as Cyril Fox and Frank Stenton began to question the veracity of these words. They admitted that the wall was “from sea to sea” , although not continuously but only in places where the orography did not constitute a natural defense by itself, and doubting that the author was Offa. Others, such as Frank Noble or David Hill, qualify these doubts by suggesting that the unbuilt areas may have been equipped with wooden palisades, a material that is not usually preserved.

In contrast, Hill does not believe that the Offa’s Dyke from sea to sea but would be shorter, or it may have formed the main core of more sections of wall built by other monarchs (Offa's predecessor on the throne, Ethebald, would have erected a section called Wat Wall), all remaining connected to each other. Likewise, there are those who consider, like John Davies, that the Welsh people should have been consulted because the layout seems to avoid certain corners, as if it were intended to cede those lands to the neighbor. It is difficult to know for sure, since it is a work of earth and not of stone, over the centuries it has been eroded so much that hardly a trace remains.

Thus, some sections remain buried and their excavation has been avoided so as not to damage them for now. Others can be easily visited thanks to the so-called Offa’s Dyke Path. , a tourist-cultural trail open to the public that was inaugurated in 1971 and is one of the longest in Great Britain, with nearly 283 kilometers, from the aforementioned Severn Estuary, in Sedbur (near Chepstow), to Prestatyn, in the north coast of Wales. There is also a visitor center in Knighton, where the most colorful remains of the wall are located.