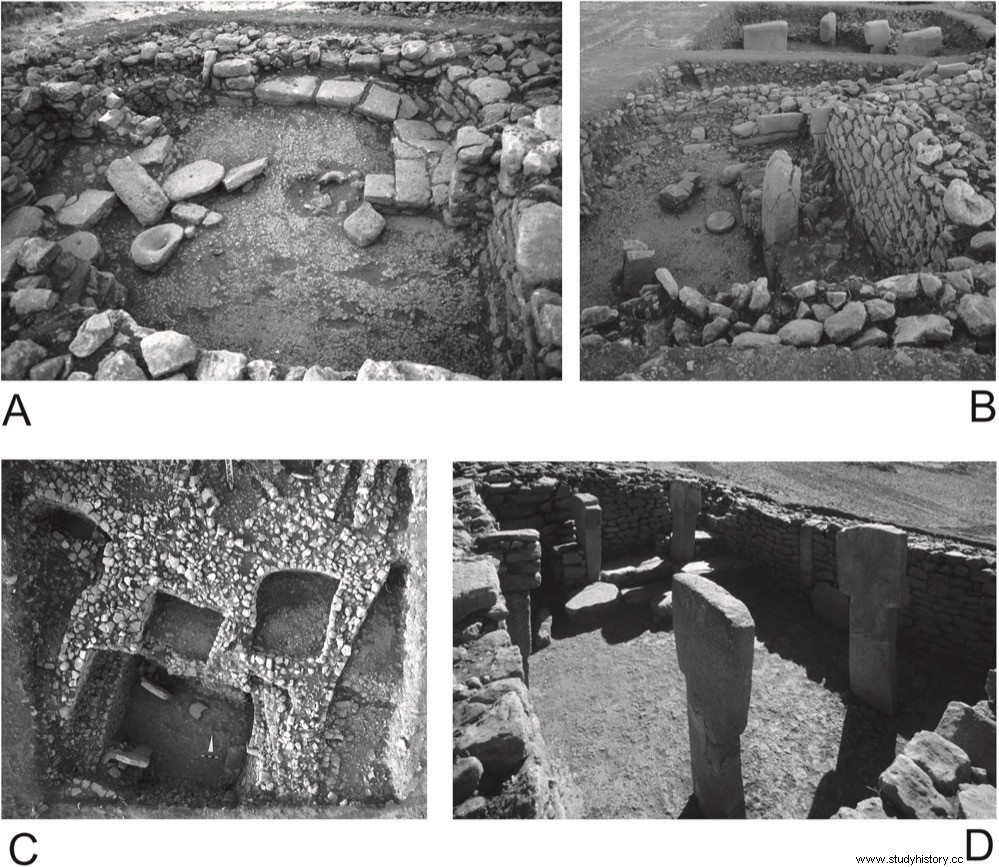

Göbekli Tepe is considered to be the oldest religious place of worship discovered, dating back to the 10th millennium BC. and deliberately buried around 8000 B.C.

It is particularly important because it was built at a time when the sedentarization process had not begun, raised by hunter-gatherers, which makes it one of the most important archaeological sites in history.

It is situated northeast of the Turkish city of Sanliurfa, ancient Edessa, near the Syrian border on a hill in southeastern Turkey.

The team of archaeologists from the German Archaeological Institute working on the site recently published a study titled Cereal Processing at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey , in which they analyze the processing of cereals in the place and its role in the early Neolithic (X-IX millennium BC).

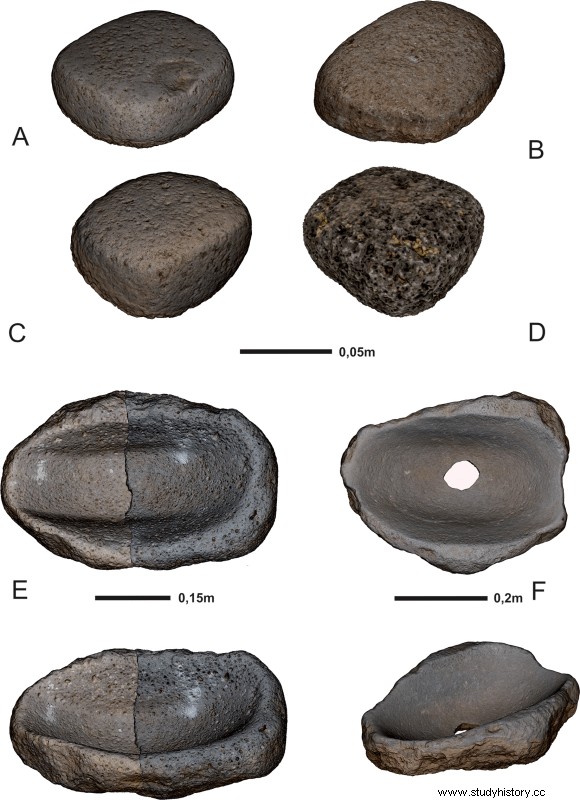

It highlights the striking abundance of tools found related to food processing, including more than 7,000 grinding slabs, bowls, hand stones and mortars, which have not been studied in detail until now.

Through formal, experimental, and macro and microscopic analyzes of the objects and their wear and tear, the study reveals that the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe were able to produce standardized and efficient grinding tools, most of which were used for the processing of cereals. An analysis of phytoliths confirmed the massive presence of cereals at the site, filling the gap left by carbonized macro-debris that has barely been preserved.

According to the study the organization of work and food supply has always been a central issue in research at Göbekli Tepe, since the construction and maintenance of the monumental architecture would have required a considerable workforce . The researchers' analysis of the tools revealed a relationship between food preparation and the rectangular buildings of the second construction phase, which surround the central circular buildings.

The researchers found evidence that extensive plant food processing and archaeozoological data point to large-scale hunting of gazelle between mid-summer and fall . Since no large storage facilities were found or identified at the site, the authors argue that food production was for immediate consumption. Therefore, they interpret these peaks of seasonal activity at Göbekli Tepe as evidence of the organization of large festivals associated with construction work at the site.

This complements the image obtained from the analysis of the animal remains, and supports the hypothesis that, in summer and autumn, large meetings were held there with the aim of attracting workers to contribute to the construction of the complex.