If today's political analysts are wondering when the republic will fall and the empire will begin, in that juicy historical analogy of comparing Rome to today's United States, you don't have to look too hard to find other similarities between the two. If North Americans boast of being the land of opportunity, ancient Rome also provided avenues for growth and success, as far as possible.

A good example of this can be Marco Virgilio Eurisace, a slave who achieved freedom, made his fortune as a baker, and built a monumental tomb to rest eternally with his wife around the year 30 BC

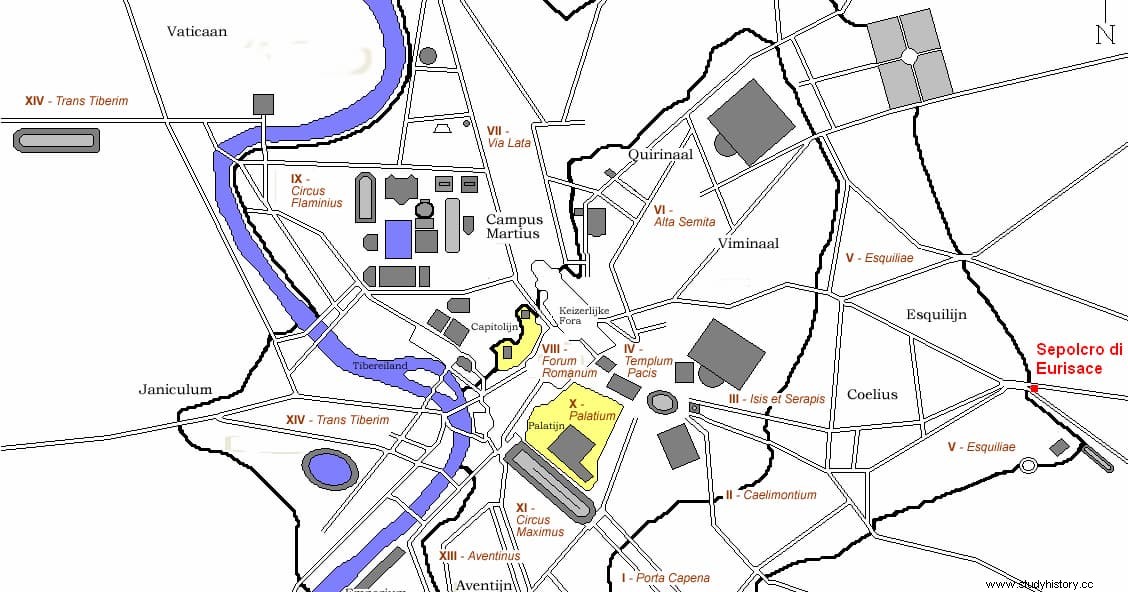

The construction, which is known as Baker's Tomb , was embedded in the later Aurelian Wall of the city, built in the 3rd century AD, and today can be seen behind the Porta Maggiore through which the Via Praenestina and Via Labicana entered Rome.

Not much is known about the life of Marcus Virgil Eurisace, except that he was a slave, achieved freedom and made his fortune with a bakery business in Rome in the first century BC, probably supplying the bread that was used for the public ration. Although there is nothing in the tomb inscription to suggest that he was indeed a freedman, there are several indications of this. First of all the form of his name, composed of praenomen and name followed by a cognomen Greek, a typical nomenclature of freedmen that combined his original name with that of the family to which he had belonged.

In addition, the lack of mention of his parentage, which he would have figured in a tomb of a freeborn, as well as his status as a bread maker, which a Roman would never have commemorated, make the difference. The same as the shape and style of the tomb, too vulgar for the taste of the time.

In any case, Eurisace, who built the tomb for himself and his wife Atistia, managed to raise it to a prominent position. As burials within the sacred boundary of the city were prohibited, those who could afford it built a tomb as close as possible to the entrance gates. Normally following the course of the roads that left Rome. But Eurisace's is in a particularly prominent place, at the junction of the Via Praenestina with the Via Labicana just before entering Rome. In fact, it is believed that its trapezoidal shape is a consequence of the limited space available, due to the presence of other tombs. Thus, the long sides measure 8.55 and 6.75 meters, while the short ones measure 3.77 and 5.44 meters.

Three sides of the structure still remain intact, with one part underground. On the first floor there are paired columns with no space between them and pilasters that end in capitals that combine scrolls on the sides with plant forms in the center, in a rather unorthodox effect.

The upper floor shows circular openings that may be a representation of the kneading vessels in bakery ovens. Under the upper cornice runs a frieze with reliefs that show various stages of the operation of a bakery of the time:on the south side, the delivery and grinding of the grain and the sifting of the flour; in the north mixing and kneading, creating round loaves and baking in the oven; in the west the stacking of loaves in baskets and their weighing.

The current total height is about 10 meters, but it must have been higher before the Aqua Claudia was built on it. , the aqueduct completed by Claudius in AD 52. It is believed that the roof must have had a pyramid shape. The part of the inscription that still survives reads:EST HOC MONIMENTVM MARCEI VERGILEI EVRYSACIS PISTORIS REDEMPTORIS APPARET (This is the monument of Marcus Virgil Eurisace, baker, contractor, obviously).

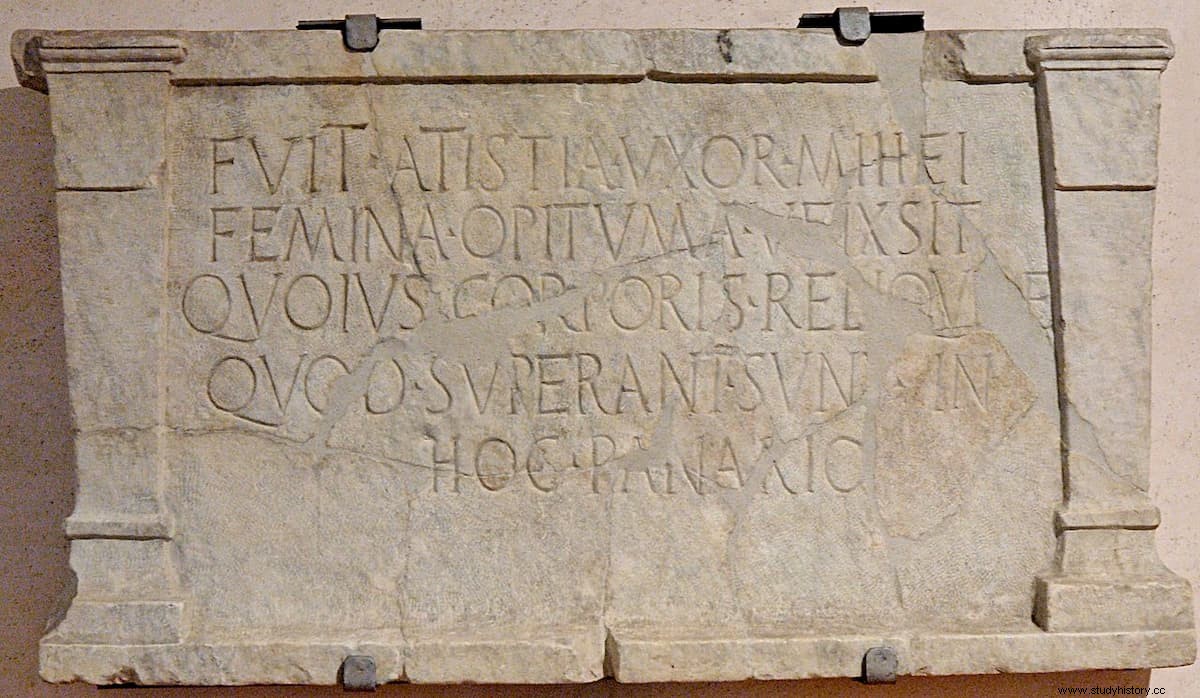

The tomb was discovered when Pope Gregory XVI ordered in 1838 to demolish the towers erected by Honorius at the Porta Maggiore. Inside the cylindrical tower, between the two arches of the door, the tomb appeared (today placed in front, outside it) and several related elements:a full-length relief showing a man and a woman with toga and palla (today in the Capital Museums); an inscription indicating that the remains of Atistia, a good wife, were placed in a bread basket, FUIT ATISTIA UXOR MIHEI FEMINA OPITUMA VEIXSIT QUOIUS CORPORIS RELIQUAE QUOD SUPERANT SUNT IN HOC PANARIO; and an urn in the shape of a panera (or basket for bread) that is now preserved in the Museum of the Baths. All these elements were part of the lost east façade of the tomb.