The story of Laocoön, the Trojan priest who was attacked and killed along with his two sons by giant snakes for trying to unmask the Trojan Horse ruse, is well known in Greek mythology. The tragic story of Laocoon has been related by numerous Greek poets, such as Apollodorus and Quintus of Smyrna. The latter described in detail the hair-raising fate of Laocoön in his epic poem Posthomericas (The fall of Troy). The famous Greek playwright Sophocles and the Roman poet Virgil also mention Laocoön, whose story is one of the most famous of the Hellenistic age.

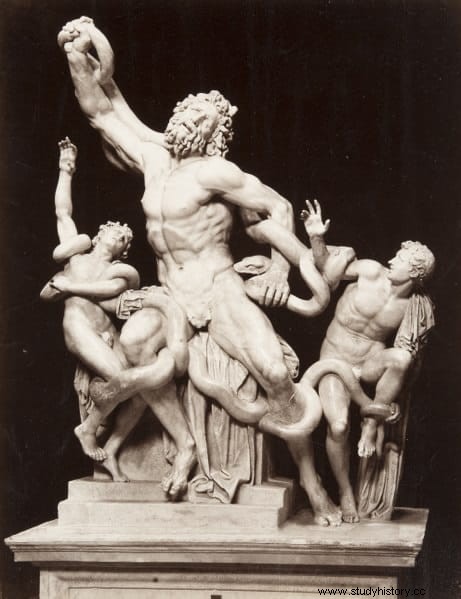

An even more tangible representation of Laocoon's gruesome end, from the same period, is the admired marble statue titled Laocoon and his sons , which is now in the Vatican Museums in Rome. Historians believe that it is the same statue that was praised by Pliny in his Natural History . According to this ancient historian and philosopher, the group of statues was carved from a single block of marble (later proven to be a mistake) by three talented artists.

In the center of the sculpture is the imposing figure of Laocoön; His muscular body struggles to resist the grip of two snakes that have become entangled in his legs and arms. With his left arm, the priest has grabbed hold of one of the snakes, but his efforts to drive the reptile away are in vain. The snake's head is positioned just above his hips, ready to deliver a deadly bite.

His right arm is bent behind his back, compressed by the coils of the same snake. To his right is his youngest child completely enveloped by the coils of the second serpent. He tries to pull the snake's head away from his body, but the venomous bite has already taken place. Under the effect of the toxin coursing through his veins, the boy can barely stand. His older brother, on the left, watches in horror and desperation as he tries to free her ankle from the second's tail.

When in 1506 the Laocoon and his sons were discovered in a vineyard under the remains of the Baths of Titus, Pope Julius II immediately sent Michelangelo and the Florentine architect Giuliano da Sangallo to inspect the find. Sangallo immediately identified the statue as the one described by Pliny. But while Pliny was right about the magnificence of the execution, the statue was not carved from a single block of marble.

However, over the centuries few scholars have doubted that the Laocoön group is the same one that Pliny speaks of. As with many archaeological finds, Laocoon and his sons it was not found intact. Some pieces were missing, such as the youngest son's left arm, the eldest son's right hand, as well as some of the serpent's coils. Pope Julius II wanted to restore the missing pieces and commissioned the project to the Vatican architect Donato Bramante, who in turn called a contest to see who was capable of giving the best version of the restoration of the arm.

Michelangelo suggested that Laocoön's missing arm be bent backwards, as if the Trojan priest were trying to pluck the serpent from his back. The Italian painter and architect Raphael, a distant relative of Bramante, favored an outstretched arm. In the end, architect and sculptor Jacopo Sansovino was declared the winner, whose version with his arm outstretched matched Raphael's own vision of what the statue should look like.

The statue was repaired in 1532, some two decades later, by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli, a student of Michelangelo, who fitted the Laocoön with an even straighter version of the outstretched arm. This became the standard version of the sculpture until in 1906, in a strange twist of fate, an ancient bent-back arm was discovered in a Roman workshop, a few hundred yards from where the group had been found. statue four hundred years earlier.

Ludwig Pollak, the archaeologist who found the arm, noted a similarity in art style to the Laocoön group, and suspecting that it was one of the missing pieces of sculpture, he presented the broken arm to the Vatican Museums. The curator kept the arm in the museum's storage room and quickly forgot about it, until it was rediscovered half a century later.

The holes in the arm matched perfectly with those in the statue, so there was no doubt as to where the fragment came from. In 1957, the museum withdrew Montorsoli's restoration and placed the bent arm as Michelangelo had suggested, vindicating the great Italian sculptor's argument long after his disappearance.

This article was published in Amusing Planet. Translated from English and republished with permission.