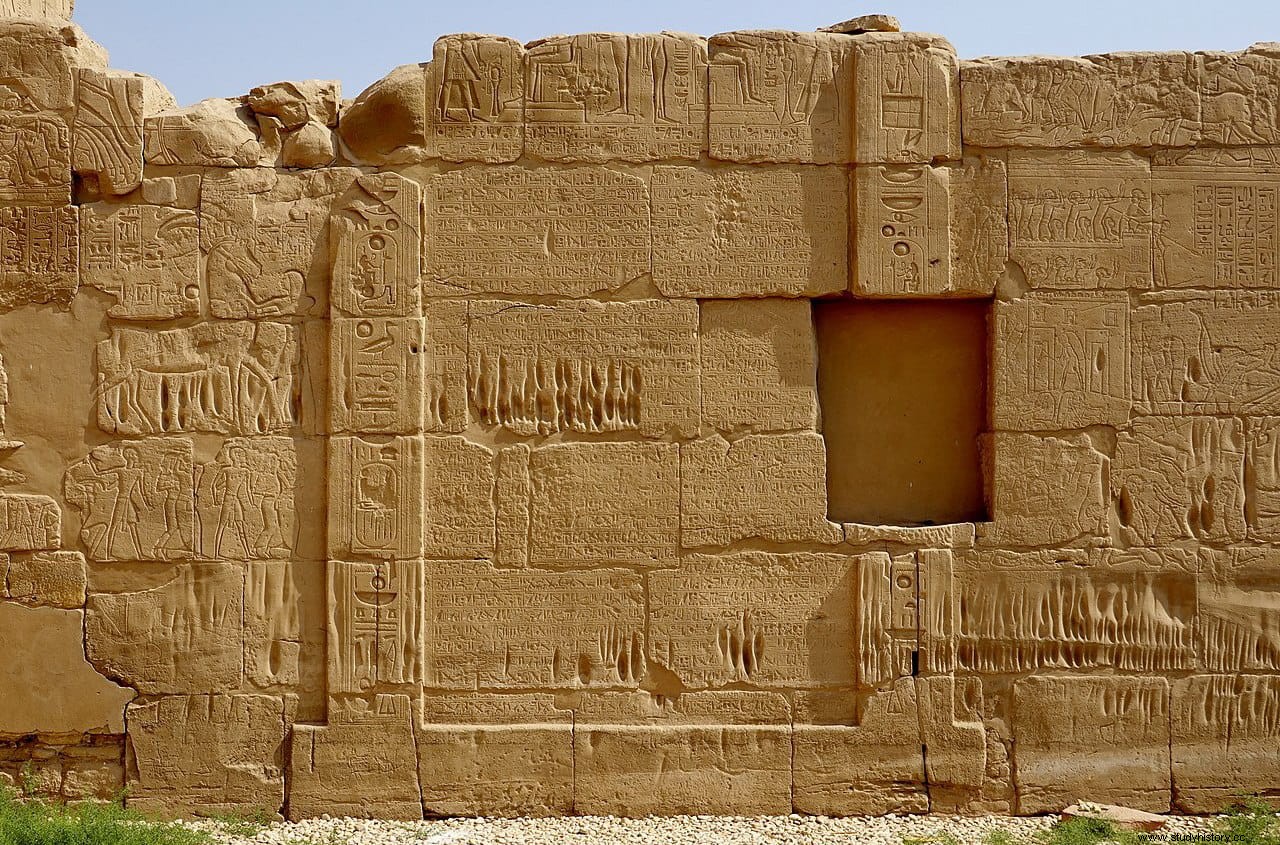

On the walls of the temple of Karnak, near Luxor (Egypt), and in the temple of Pharaoh Ramses II in Thebes, there are engravings that describe a great battle against the Great King of Khatti and a peace treaty that was forged with them.

Known since antiquity, hieroglyphs were first translated by Jean-François Champollion in the early 19th century, sparking renewed Western interest in Ancient Egypt.

In 1858 the Great King of Khatti was identified as the Hittites who ruled in central Anatolia, in present-day Turkey. Eight years later, in 1906, the German archaeologist Hugo Winckler discovered and excavated the Hittite capital, Hattusa, in the fortified ruins of Boğazkale, in Turkey.

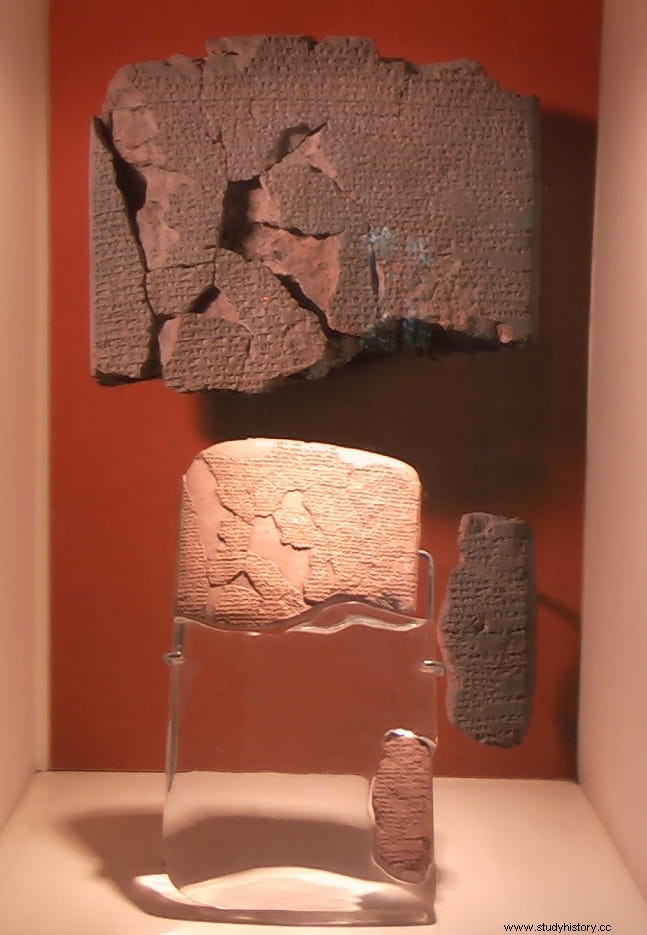

In the remains of the largest palace, they unearthed 10,000 clay tablets with cuneiform writing documenting many of the Hittites' diplomatic activities. The find also included three tablets on which the text of a treaty was inscribed that corresponded to those found on the walls of Egyptian temples. Winckler immediately understood the importance of the discovery. He wrote:

The Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty, also known as the Treaty of Qadesh, is the first peace treaty on record. It is also the only Ancient Near Eastern treaty for which both sides' versions have survived.

It was signed to end the longstanding animosity between the Hittite Empire and the Egyptians, who had fought for more than two centuries to gain control of the lands of the eastern Mediterranean. The conflict culminated in an attempted Egyptian invasion in 1274 BC. who was arrested by the Hittites in the city of Qadesh, on the Orontes River, in present-day Syria.

In the Battle of Qadesh, both sides suffered heavy casualties, but neither side was able to decisively prevail in either the battle or the war. The conflict continued inconclusively for some fifteen more years before the treaty was signed. Although it is often called the Treaty of Qadesh, it was actually signed long after the battle, and Qadesh is not mentioned in the text.

The treaty is believed to have been negotiated through intermediaries without the two monarchs meeting in person. Both parties had common interests to achieve peace; Egypt faced a growing threat from the Sea Peoples, while the Hittites were concerned about the growing power of Assyria to the east. The treaty was ratified in the 21st year of the reign of Ramesses II (1258 BC) and continued in force until the Hittite Empire collapsed before the Assyrians, almost a century later.

The peace treaty of Ramses II and Hattusili III is remarkable because we know its exact wording. Like any modern agreement, the treaty is divided into points and each party makes promises of brotherhood and peace to the other depending on the objectives. They agreed that they would not commit acts of aggression against each other, that they would repatriate each other's refugees, and that they would help each other.

Should one foreigner attack Egypt or the Hittites, the other would provide military aid:

The treaty ends with a declaration that the gods are called to bear witness, and in case of breaking the treaty, a punishment from the gods would be received:

After forming an alliance with Hatti, Ramesses began directing his wealth and his energies towards domestic projects, leading to extensive building projects such as the completion of his great rock-cut temples at Abu Simbel. There is also evidence that Ramses tried to establish stronger family ties with Hatti by marrying a Hittite princess.

The treaty in its final form was drawn up at Qadesh in consultation with the Egyptian ambassadors. When it was in its final form, it was inscribed on a silver tablet and taken to Egypt. Following Ramesses' approval, a counterpart was drafted in his own name, taking phrases from the Hittite original and making only a few minor modifications.

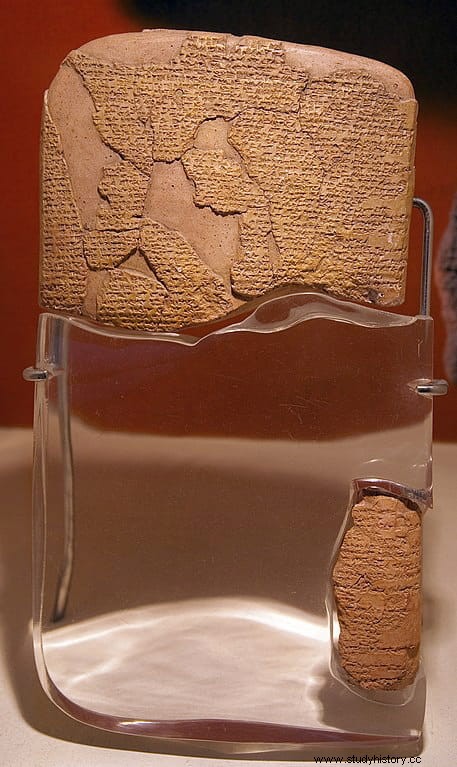

Finally, the version made in the name of Ramses was engraved on another silver tablet, stamped with the pharaoh's seal, and sent to Hatti. Hatti scribes then prepared written copies on clay tablets to keep in the royal archives. It was these copies that Hugo Winckler discovered. The original silver tablets have been lost, probably looted and melted down long ago.

Two of the clay tablets are now on display at the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, while the third is on display at the State Museums in Berlin, Germany. A copy of the treaty is prominently displayed on a wall at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

A copy of the Egyptian version, as we said at the beginning of the article, is engraved in hieroglyphics on the walls of two temples of Pharaoh Ramses II in Thebes:the Ramesseum and the Karnak temple.

This article was published on Amusing Planet. Translated and republished with permission.