Classifying Alfonso X as a historian is a controversial decision, even more so when it is evident that it was not the monarch himself who wrote the works attributed to him. However, such is the importance that the General Estoria and the Estoria de España they had on medieval historiography that forces us to include the king who promoted them among the great historians. The novelties in the preparation, elaboration, technique and content of both texts are such that, if they may not reach the category of revolutionary works, they constitute in any case a break with the previous historiographical tradition. Hence the importance that has been attributed to the work of the Castilian monarch as a promoter of historical discipline.

Classifying Alfonso X as a historian is a controversial decision, even more so when it is evident that it was not the monarch himself who wrote the works attributed to him. However, such is the importance that the General Estoria and the Estoria de España they had on medieval historiography that forces us to include the king who promoted them among the great historians. The novelties in the preparation, elaboration, technique and content of both texts are such that, if they may not reach the category of revolutionary works, they constitute in any case a break with the previous historiographical tradition. Hence the importance that has been attributed to the work of the Castilian monarch as a promoter of historical discipline.

Alfonso X el Sabio was born in Toledo on November 23, 1221, the result of the marriage between Fernando III el Santo and Beatriz de Suabia. We know little about his childhood and it is disputed whether he spent his early days in Galicia, where he would learn the language of the cantigas, or whether, on the contrary, he lived in Burgos. It is probable that he participated in the campaign for the conquest of Murcia in 1243 and a year later he was at the signing of the Treaty of Almizara, which established the limits between the Crowns of Aragon and Castile in the Kingdom of Valencia and in who also remembered his marriage to Violante de Aragón.

On the death of his father, on May 30, 1252, Alfonso acceded to the throne of Castile and León. Also crowned as King of Seville, the obligation to continue the conquest of Lower Andalusia falls on him. Parallel to the military campaigns, he sought to provide the Kingdom of Castile with common laws for all its subjects and strengthen the power of the monarchy, which led him to clash with the nobility. The unifying will was embodied in the extensive legal code written in romance and organized around the number seven (the Partidas) and in the Fuero Real, an instrument to unify municipal legislation, granted to different cities.

Two of the great milestones of the monarchy of Alfonso X ended in resounding failures. The attempt to extend the thrust of the reconquest to North Africa, as a crusade, ended in 1263 with the taking of only a few squares near the city of Oran, which could not even be preserved. In addition, it had the effect of inciting a Mudejar rebellion in the peninsula that came to conquer several Andalusian cities until it was harshly repressed. On the other hand, the so-called “Date of the Empire ”, that is, the aspiration, after the death of Emperor Frederick II in 1250, to the throne of the Holy Germanic Empire, in his capacity as son of Beatrice of Swabia and grandson of Philip of Swabia, did not give the expected results either, largely by the opposition of the pontificate that frustrated the two attempts to get hold of the imperial purple. Finally, pressured by Pope Gregory IX, Alfonso X would desist from his attempt in 1275. That same year the Spanish monarch had to face the invasion of the Benimerines who took Tarifa and Algeciras.

The last years of Alfonso X's life were shrouded in tragedy and conflict. The death of his first-born son generated tensions between his grandson and his second son, Sancho, over the succession to the throne. The conflict led to the deposition of the king and the outbreak of a civil war:Alfonso X's support was limited to Murcia and Seville, while the rest of Castile and the vast majority of the nobles favored Sancho. When he was organizing his army, he died in Seville on April 4, 1284.

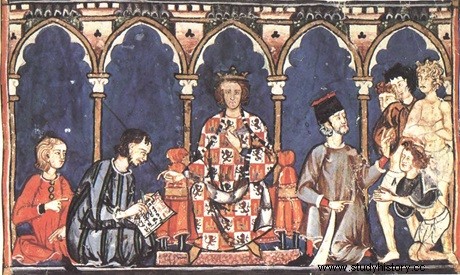

Alfonso X was not only concerned with establishing solid legal principles for the kingdom and the monarchy, he also wanted to improve the cultural level and education of his subjects. Thanks to the arrival of numerous scholars and scientists to the Castilian court, various works were written on astronomy, pure sciences, religion, literature and history. It will be in this last discipline where his most renowned works appear, the General Estoria and the Estoria de España (also known as the First General Chronicle ). There is, however, a certain consensus in denying the authorship of both works to the monarch and it seems more likely that he only participated indirectly in their elaboration and that, on occasions, he supervised some passages; but his condition of "wise", although it may be true, did not reach the cultural level necessary to carry out a task of such magnitude.

Alfonso X was not only concerned with establishing solid legal principles for the kingdom and the monarchy, he also wanted to improve the cultural level and education of his subjects. Thanks to the arrival of numerous scholars and scientists to the Castilian court, various works were written on astronomy, pure sciences, religion, literature and history. It will be in this last discipline where his most renowned works appear, the General Estoria and the Estoria de España (also known as the First General Chronicle ). There is, however, a certain consensus in denying the authorship of both works to the monarch and it seems more likely that he only participated indirectly in their elaboration and that, on occasions, he supervised some passages; but his condition of "wise", although it may be true, did not reach the cultural level necessary to carry out a task of such magnitude.

The General Story It is divided into six large sections (the same as those used by Saint Augustine):from creation to the flood; from the flood to Abraham; from Abraham to David; from David to the captivity of the people of Israel; from the captivity to the death of Christ and from the death of Christ to the reign of Alfonso X. Each and every one of them organized chronologically and with the Bible as the axis around which the narrative revolves. For its part, the Estoria de España it is divided chronologically according to the different peoples that had dominated the Iberian Peninsula (Greeks, "almujuces", Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals and Goths).

History is conceived, in the work of the Castilian monarch, as a segment whose origin dates back to the beginning of time and whose end is in our days. The birth of Christ accentuates the linear sense of time by producing a fracture between the beginning and the end. With the General Estoria Alfonso X intended “to put all the dates indicated as well from the stories of the Bible as from the other great things that happened in the world since it began until our time ”. The purpose was undoubtedly excessive and it was never concluded:the Sixth Part, which was going to cover everything from Jesus Christ to the Castilian king himself, would remain unfinished.

The fluid contact in the Castilian cities between Arabs and Europeans made it possible for the authors of Alfonsine works to have access to Arab and Jewish historical culture, classical ancient history and the new European currents. The General Estoria , although it obviously uses biblical chronology and texts, it goes much further and uses both classical sources (the Metamorfosi s of Ovid, for example, or the Naturalis Historia of Pliny, or the Farsalia of Lucan) and Jewish (Flavius Josephus), both proto-Christian and post-Roman as well as medieval (the Pantheon of sources of Godofredo de Viterbo). Numerous "profane" stories are included in it, from those with a mythical content to the historical ones. In the Estoria de España we find, in addition to the previous sources, a clear influence of the works of Rodrigo Ximenez de Rada (De rebus hispaniae ) and Lucas de Tuy (Chronicon mundi ).

Despite the importance that Christianity has in the medieval mentality, it is surprising how the divine influence is relegated to the background (at least for the traditional canons of that time) , especially in the Estoria de España . In some parts of the works, even, the "profane" content numerically overflows the strictly "sacred", even when it is exposed in parallel to it. The facts seek to be narrated as plausibly as possible and subject to Catholic doctrine, but this does not prevent certain events from being questioned at certain times and contradictory views are allowed.

It is remarkable in the General Story the frequent appeal to classical texts, which were made available to medieval readers centuries before they were generalized by the Italian Renaissance. And the use of Arabic sources is also striking (“writings of wise Aravigos ”) that Alfonso X incorporates with no little respect:see, for example, the chapter entitled “of the logar and of the time of the birth of Abraham according to the Aravigos ”.

The didactic function of the work demands the union between the spiritual and the human, the profane and the sacred. The stories that are collected show how the only way to overcome the pessimistic view of history (the inevitable Last Judgment) lies in the individual and collective effort to achieve greater knowledge. Culture becomes an element of salvation and history, with its many examples, shows us the way to achieve universal knowledge, which no longer resides only in oral tradition but also in writing and is applicable to both believers and to non-believers.

The didactic function of the work demands the union between the spiritual and the human, the profane and the sacred. The stories that are collected show how the only way to overcome the pessimistic view of history (the inevitable Last Judgment) lies in the individual and collective effort to achieve greater knowledge. Culture becomes an element of salvation and history, with its many examples, shows us the way to achieve universal knowledge, which no longer resides only in oral tradition but also in writing and is applicable to both believers and to non-believers.

Along with the purely didactic objective that permeates the historical work of Alfonso X, we also find a political program that seeks to enhance the image of the king and the monarchical institution. Casual comparisons or subtle comparisons between mythical or real characters and Alfonso X, which appear scattered throughout the works, make it difficult to distinguish when we are dealing with the political monarch or the historian monarch. This same duality is perceptible in the Estoria de España where for the first time in medieval historiography the historical subject is going to be a "people/nation" (take into account the nuances of this term, without forgetting the context in which it occurs). Until then, most of the works addressed either universal history (Eusebius of Caesarea or Paulo Orosius) or that of entire peoples (Isidore of Seville or Gregory of Tours). However, Alfonso X gives the peninsula a certain territorial and historical unity that makes it the protagonist, and places the arrival of the Goths and their loss at the hands of the Muslims as turning points in his history.

Another of the great novelties introduced by Alfonso X was the use of the vernacular language (Castilian) to the detriment of Latin. We do not know with certainty if it is the first work on history that used this system but, if not, none of the previous ones had the importance achieved by the Alfonsine works.

Both the General Story like the Estoria de España they supposed a significant transformation in the medieval historiographical method. Until the appearance of both, the chronicles predominated, that is, the mere relationship of narrated events, while Alfonso X tries in his works to reconstruct the past through a detailed study of the sources and with an evident informative desire. Beyond the authorship of the writings, the impulse that the Wise King gave to the historical discipline is undeniable, in a complex era in which the kings were more interested in fighting than in culture.